Resection of Hilar Cholangiocarcinoma

Ryan T. Groeschl

T. Clark Gamblin

DEFINITION

Hilar cholangiocarcinoma (HC), also referred to as Klatskin’s tumor, is an extrahepatic cancer of biliary epithelial origin near the confluence of the right and left hepatic ducts. The hepatic artery and portal vein are in close proximity to the bile duct, and vascular involvement is common. Given the limited effectiveness of other therapies, margin-negative resection is the optimal treatment. Although multimodal therapy combined with transplantation is also a potential approach to HC,1 this chapter focuses on the resection technique for this biliary disease.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

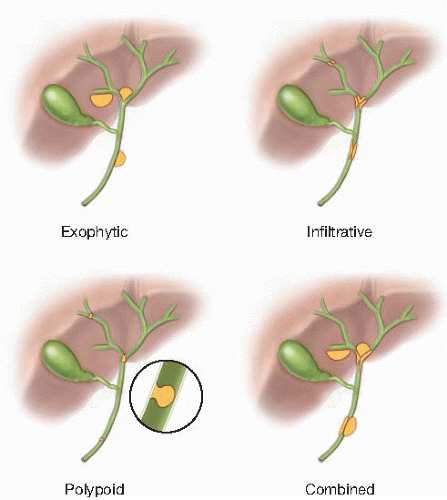

Growth patterns for HC may be exophytic, infiltrative, polypoid, or any combination thereof (FIG 1). The differential diagnosis includes pathologies that may mimic any of these appearances.

Papilloma—composed of vascular connective tissue and covered with columnar epithelium; low-grade malignant potential

Adenoma—glandular tissue surrounded by fibrous stroma; low-grade malignant potential

Benign biliary stricture from recurrent pyogenic cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, choledocholithiasis, Mirizzi’s syndrome, previous surgery, or trauma.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Successful hepatectomy must maintain an adequately healthy liver remnant. Initial assessment of the patient must not only focus on the malignancy itself but also on general liver function. Underlying liver dysfunction (due to chronic alcohol exposure, viral hepatitis, fatty liver disease, etc.) may alter operative planning and the minimum remnant required.

History

Symptoms: jaundice, itching, unintentional weight loss, abdominal pain

Broader aspects of patient history: gallstones, cholangitis, primary sclerosing cholangitis, ulcerative colitis, previous surgery or trauma, viral hepatitis, cirrhosis, alcohol consumption, international travel, obesity, diabetes, hyperlipidemia, bruising, immune deficiency

Physical exam

Jaundice or scleral icterus; muscle wasting may be present.

If disease occludes cystic duct, gallbladder may be palpable (Courvoisier’s sign).

Assess for stigmata of cirrhosis, portal vein thrombosis, or portal hypertension: ascites, encephalopathy, spider angiomata, skin telangiectasias, palmar erythema, bruising.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Transabdominal ultrasound

May identify duct dilation and large hilar tumors, but primarily functions as a screening tool

Doppler may identify narrowing or thrombosis of the hepatic artery or portal vein.

Cross-sectional imaging: computed tomography and magnetic resonance

Good visualization of mass lesions and ductal dilation

Staging: may identify intraabdominal lymphadenopathy and/or metastases

Contrast enhancement allows assessment of vascular involvement and identification of anomalous hepatic inflow, which are critical to operative planning.

Signs of cirrhosis or portal hypertension may be present: irregular hepatic capsule, caudate hypertrophy, cavernous transformation, hypersplenism, ascites, recanalized umbilical vein.

Cholangiography

Magnetic resonance cholangiopancreatography

Noninvasive; allows visualization and three-dimensional reconstruction of ductal anatomy

Does not provide opportunity to sample tissue

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography

Allows visualization of ductal anatomy, provides opportunity for brushing or biopsy, and allows stenting in case of biliary obstruction

Invasive; risk of procedure-induced pancreatitis

Cholangiography via percutaneous catheters

If percutaneous biliary drainage catheters have been placed, contrast can be used to delineate ductal anatomy and also allow brushings.

Ideally, such catheters are placed in the future remnant liver or bilaterally.

Endoscopic ultrasound

Allows evaluation of the duct and regional lymph nodes, which may also be sampled with fine needle aspiration or core biopsy when available (19 gauge to 22 gauge)

Intraductal fiberoptic direct visualization (with biopsy) and intraductal ultrasonography are available at some centers.

Positron emission tomography

Fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) avidity is typically limited to mass lesions greater than 1 cm but provides poor quality for identifying cancers with infiltrative growth; hence, limited use beyond standard cross-sectional imaging for assessing primary tumor.

May identify occult metastatic disease

Laboratory evaluation

Cholestasis may be indicated by elevated bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, and gamma-glutamyltransferase levels.

Albumin and prothrombin time evaluate synthetic function.

Aspartate and alanine aminotransferase levels are often normal.

Low platelet levels may reflect hypersplenism due to portal hypertension.

Elevations in carbohydrate antigen 19-9 (CA 19-9) or carcinoembryonic antigen may be elevated in patients with HC.

CA 19-9 may be spuriously elevated in the setting of jaundice.

When workup reveals tumor marker elevation, these levels may be followed after resection to assess for disease recurrence.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Patients with jaundice should be drained either endoscopically or percutaneously to optimize liver remnant function.

Operations for HC involve the dissection of critical structures, biliary and vascular reconstruction, and adaptation to intraoperative findings. Expertise in hepatobiliary anatomy and surgical technique is essential. In particular, familiarity with common patterns of anomalous ductal and arterial hilar anatomy (FIG 2) will prevent injury to unintended structures. Features of unresectability are shown in Table 1.

When a diminutive liver remnant is anticipated, preoperative angioembolization of the contralateral (tumor-supplying) portal vein should be pursued in an attempt to hypertrophy the potential remnant.

The Bismuth-Corlette classification is used to describe the extent of right and left duct involvement (FIG 3). Careful review of cholangiography and cross-sectional imaging will identify resectable patients and aid in operative planning.

Right hepatectomy or trisectionectomy is generally indicated for types II and IIIa tumors.

Left hepatectomy, and especially left trisectionectomy, is uncommonly performed and often carries a higher complication rate. This type of resection is usually reserved for type IIIb tumors, or those cases where the future left-sided remnant would be inadequate for type II tumors.

Type IV tumors are unresectable unless a full sectoral branch is uninvolved and free of tumor.

Type I HC may occasionally be amenable to local biliary resection alone; however, R0 rate and thus survival have been directly linked to the use of hepatic resection.2

Apparent invasion of the portal vein or vena cava does not preclude resection. Large tumors can narrow adjacent vessels on imaging; however, this may be mass effect and not necessarily represent invasion.

Contraindications to resection include distant metastatic disease and bilobar liver involvement.

Although enthusiasm has grown for laparoscopic liver surgery, the dissection and reconstruction required for resection of HC currently requires laparotomy in most cases. However, a preliminary laparoscopy (performed immediately before planned resection) will identify occult disease in at least half of unresectable patients, who are then spared laparotomy.3

Intraoperative ultrasound should be used liberally throughout the operation to assess extent of disease, location of ducts, and location/patency of vessels.

Table 1: Liver-Specific Criteria for Unresectable Klatskin Tumors | ||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||

Positioning

Supine position with arms perpendicular to body axis (FIG 4)

Sterile skin preparation extends cranially beyond the nipple line, caudally to the groins, and laterally to the posterior axillary lines (particularly on the right side).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree