Repair of Congenital Defects: Bochdalek Congenital Diaphragmatic Hernia

Scott A. Anderson

Mike K. Chen

DEFINITION

A Bochdalek congenital diaphragmatic hernia (CDH) refers to a defect in the posterolateral diaphragm. The abdominal viscera partially translocates through the defect in the thorax in the developing fetus. This affects the growth and maturation of both lungs. The size of the defect can range from fairly small to complete diaphragmatic agenesis. Affected infants are born with pulmonary hypoplasia, lung immaturity, and pulmonary hypertension, to varying degrees. Successful management of these issues is most critical to a favorable outcome.

The incidence of CDH is 1 in 2,000 to 1 in 5,000 births overall. Approximately 80% will occur on the left side; bilateral defects are rare. It continues to be one of the more challenging congenital anomalies in pediatric surgical patients.

DIFFERENTIAL DIAGNOSIS

Prenatally and postnatally, Bochdalek CDH can be mistaken for a number of other congenital thoracic anomalies. These can include Morgagni CDH, diaphragmatic eventration, congenital cystic lung disease, esophageal hiatal hernia, and primary lung agenesis.

The various imaging and diagnostic studies used to distinguish among these are discussed in a subsequent section.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Many, but certainly not all, CDH patients are born with the diagnosis already made on prenatal ultrasound. A team of neonatologists, high-risk obstetricians, and pediatric surgeons are involved in their perinatal care to ensure a safe delivery and expeditious treatment. These patients are immediately resuscitated after delivery with endotracheal intubation and nasogastric decompression. Ventilation with Ambu bag and mask is avoided to minimize gastrointestinal (GI) distention, which can worsen the compression in the thoracic cavity. A strategy of spontaneous respiration and permissive hypercapnia is employed to minimize ventilatorinduced lung injury.

For those without prenatal diagnosis, patients will present shortly after birth with typical signs of respiratory distress, including tachypnea, grunting, and cyanosis. They also will commonly have a scaphoid abdomen, barrel-shaped chest, and diminished or absent breath sounds on the affected side. The heart tones are also shifted toward the contralateral side.

Ten percent to 50% of CDH patients will have other congenital anomalies, so a thorough physical examination and assessment is indicated. See Table 1.

Also, a number of syndromes have been associated with CDH including Frey; Beckwith-Wiedemann; Goldenhar; Fryns; and trisomy 21, 18, and 13. A genetics consult is warranted if any of these are suspected.

Table 1: Associated Congenital Anomalies | ||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Prenatal workup includes ultrasound and/or fetal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Evaluation of fetal karyotype via amniocentesis or other methods can provide additional information that aids in properly informing and preparing the parents.

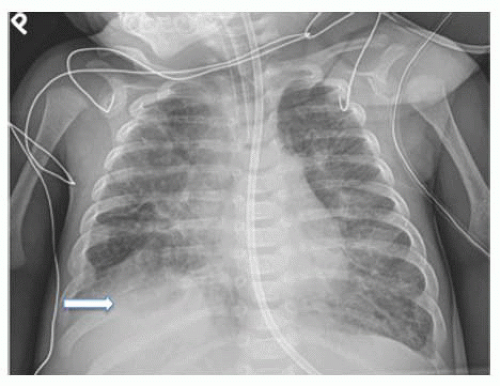

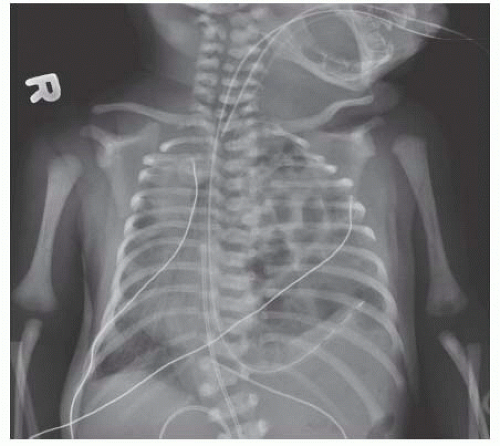

After birth, a chest radiograph is the primary diagnostic study of choice. For a left-sided CDH, this will classically show multiple gas-filled bowel loops within the left hemithorax and contralateral shift of the mediastinum (FIG 1). The presence

of the liver and/or stomach in the chest on plain film can help estimate the size of the hernia defect. A right-sided CDH may demonstrate only an elevated liver shadow if no other visceral contents have traversed the hernia defect (FIG 2).

Computed tomography, MRI, ultrasound, fluoroscopy, and upper GI series with small bowel follow-through may be used as well when the diagnosis is not certain. Diagnostic thoracoscopy or laparoscopy is recommended if the diagnosis remains unclear after appropriate imaging studies.

An echocardiogram should be obtained as part of the workup for associated congenital anomalies. It can also be useful in quantifying the degree of pulmonary hypertension and then following its treatment. Additionally, intracranial imaging with a head ultrasound is useful, particularly when perioperative extracorporeal membrane oxygenation (ECMO) is considered as part of the infant’s management.

FIG 1 • Chest x-ray in neonate demonstrating a left CDH. Note that the stomach and liver are both transposed into the left chest and the mediastinum is shifted to the right. |

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

CDH is a physiologic emergency and not usually a surgical emergency. The careful management of the neonate’s pulmonary hypoplasia, lung immaturity, and pulmonary hypertension is most critical to his or her successful outcome.

The optimal timing for surgical repair is unclear, although most current strategies include a period of medical stabilization followed by delayed operative repair.

Both open and minimally invasive techniques can be used for repair. We favor a thoracoscopic repair for a small defect in the stable patient and an open repair in the less stable patient with a larger hernia defect.

Prior to taking the patient to the operating room, all diagnostic studies should be thoroughly reviewed and the patient should be appropriately marked on the affected side.

Ensure that the airway is secure and the endotracheal tube in a stable position. Pre- and postductal oxygen saturation monitoring should be maintained.

Arterial access is ideal for perioperative and intraoperative blood gas monitoring.

The infant’s own ventilator is preferred over the typical anesthesia circuit.

If the patient is on ECMO, appropriate perioperative bleeding protocols should be initiated.

For less stable infants, it may be more appropriate for the surgical repair to take place in their neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) bed space.

TECHNIQUES

OPEN LEFT CONGENITAL DIAPHRAGMATIC HERNIA REPAIR

Positioning

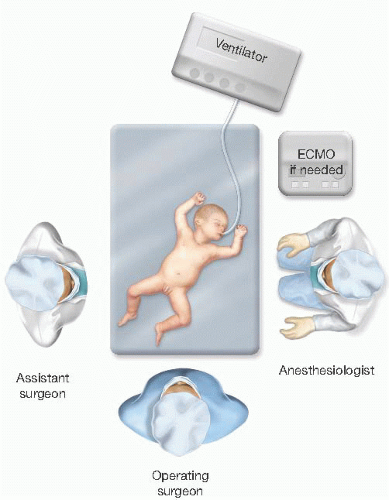

In the operating room, the infant is placed in the supine position on a shortened bed (FIG 3).

Sterile plastic drapes are used as a barrier over the infant outside of the operative field. A warming blanket is also used to maintain temperature stability.

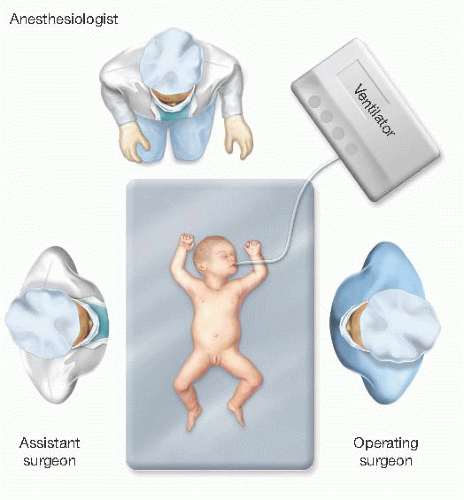

For operative repairs in the NICU, the infant is brought to the end of his or her bed at an angle, with his or her feet directed toward one corner (FIG 4).

Both the abdomen and chest are prepared as the operative fields. The umbilical catheters are secured to the patient’s lower quadrant, contralateral to the operative side.

FIG 3 • The infant is positioned in the center of a shortened operating room table. The operating surgeon stands on the side of the CDH with the surgical assistant on the opposite side. |

Incision

For a left CDH, an ipsilateral subcostal incision is made. Do not make the incision too close to the costal margin as it may leave little room to work with on the lateral chest wall and it may make closure more difficult. The subcostal incision will need to be extended across midline for larger diaphragmatic hernia defects (FIG 5).

The abdominal wall muscle and fascia are divided and the peritoneum entered. The infant’s abdominal wall may be gently stretched to help increase domain for the hernia reduction.

Hernia Reduction

First, the liver needs to be mobilized. The triangular ligament is taken down and the left lateral segment completely freed up. The falciform ligament can usually be left intact.

The liver is carefully retracted away from the diaphragmatic defect to expose the medial boundary of the diaphragmatic hernia defect (FIG 6).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree