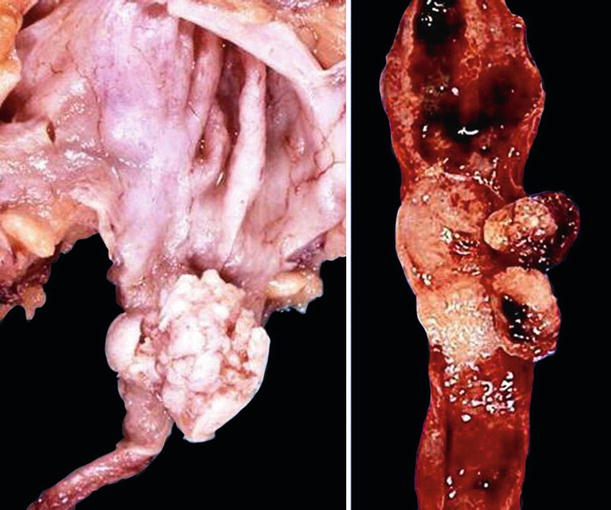

Fig. 37.1.

Fibroepithelial polyp of the ureter.

♦

Chronic inflammatory cell infiltrate and xanthoma cells may be present

Ureteral Endometriosis

Clinical

♦

Mean age at diagnosis is 51 years

♦

May be asymptomatic or present with hydronephrosis and superimposed pyelonephritis

♦

May lead to renal failure due to silent obstruction of the ureter

♦

Has a strong predilection for involvement of the lower third of the left ureter

Microscopic

♦

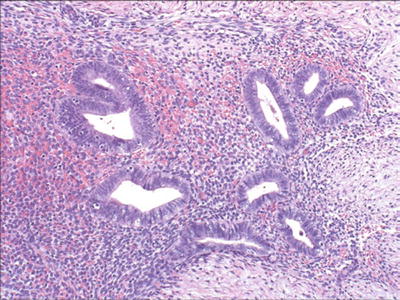

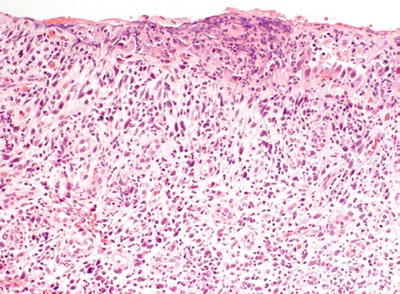

Composed of endometrial stroma, glands, (Fig. 37.2), and often hemosiderin-laden macrophages (two or more of these findings helpful for diagnosis)

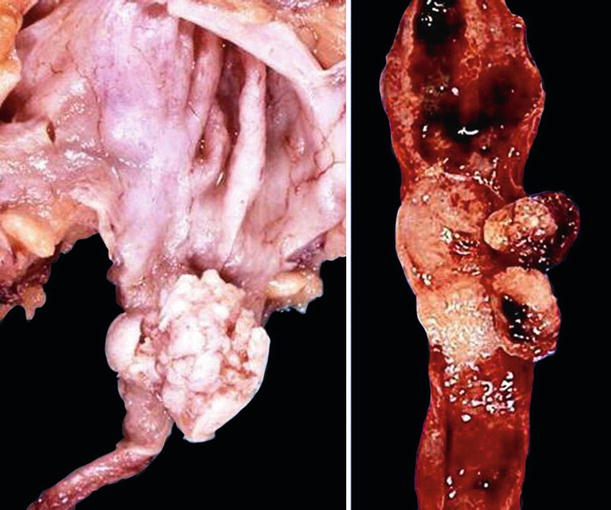

Fig. 37.2.

Ureteral endometriosis.

♦

Both extrinsic and intrinsic involvement by endometriosis may be encountered

Intrinsic disease is characterized by the presence of ectopic endometrial tissue within the muscularis propria, lamina propria, or ureteral lumen

In extrinsic disease, endometrial tissue involves only the ureteral adventitia or surrounding connective tissues

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Epithelial cells are positive for CK7, PAX-8, ER, and PR

♦

Stromal cells are positive for CD10, ER, and PR

Urethral Inflammatory Polyp

♦

Composed of inflamed and vascular stroma lined by normal or hyperplastic urothelium with inflammatory cells extending to the urothelium

Urethral Caruncle

Clinical

♦

Usually occurs in postmenopausal women at a mean age of 56 years

♦

Typically presents as a red painful mass at the external ureteral meatus

♦

The etiology remains uncertain

♦

May be asymptomatic or present with hematuria, dysuria, and pain

♦

Unrelated to viral infection

Macroscopic

♦

Pedunculated or sessile erythematous lesion in the posterior or lateral distal urethral wall

Microscopic

♦

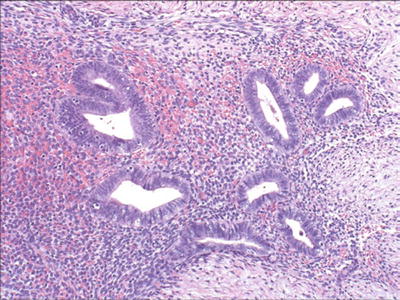

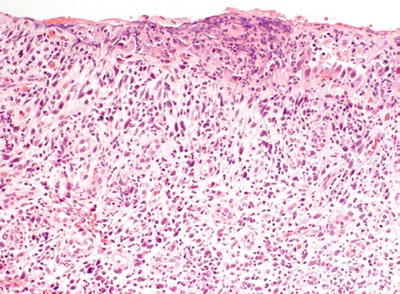

The lesion displays an exuberant proliferation of fibroblasts and endothelial cells in an inflammatory background, similar to granulation tissue (Fig. 37.3)

Fig. 37.3.

Urethral caruncle.

♦

Lacks significant cytologic atypia

♦

Mitotic figures are inconspicuous

♦

Atypical stromal cells may occasionally be present, raising suspicion for cancer; these atypical cells are cytokeratin, EMA, and ALK negative

♦

Urothelium may show hyperplasia, squamous or columnar metaplasia, or denudation

♦

Some cases may be related to the autoimmune phenomena of IgG4-associated disease

Differential Diagnosis

♦

Pseudosarcomatous fibromyxoid tumor

Reactive myofibroblasts which may display cytokeratin, ALK, and actin immunoreactivity

♦

Sarcomatoid carcinoma

Cytologic atypia and mitotic figures are prominent

Cytokeratin positive

Urethral Diverticulum

Clinical

♦

Usually affects women, and often asymptomatic

Microscopic

♦

Lined by urothelium, but squamous and glandular metaplasia can be seen

♦

Nephrogenic adenoma or carcinoma may develop in diverticula

Ectopic Prostatic Tissue

Clinical

♦

Occurs in adolescents or young adults and presents with hematuria or irritative symptoms

♦

May shed atypical cells into the urine

♦

Often located in the posterior portion of the prostatic urethra

♦

These lesions may be better classified as benign prostatic polyp

Microscopic

♦

Composed of benign prostatic glands with overlying intact urothelium

♦

PSA+ basal cell layer is detectable using high molecular weight cytokeratin and p63

Idiopathic Retroperitoneal Fibrosis

Clinical

♦

Often medial deviation of the ureter on radiological examination

♦

Firm, fibrotic tissue encases periaortic structures, leading to ureteral obstruction

♦

Middle and older age

♦

Significant proportions of cases in women are associated with clonal expansion of fibroblasts

Microscopic

♦

There are varying amounts of fibrosis with collagen deposition

♦

The lesion often shows a prominent chronic inflammatory infiltrate with lymphocytes and plasma cells

♦

Occasional lymphoid follicle formation may be seen

♦

Stromal edema and fibroplasia are also seen and in selected cases impart a myxoid appearance to the lesion, raising concern for inflammatory type myxoid liposarcoma

♦

Linked to IgG4-driven autoimmune process (IgG4-related sclerosing disease)

♦

Rare cases may mimic renal cell carcinoma

Neoplasms of the Renal Pelvis and Ureter

♦

Tumors arising in the renal pelvis and the ureter are morphologically similar to those seen in the urinary bladder (Table 37.1)

Table 37.1.

Histological Classification of Tumors of the Renal Pelvis and Ureter

Epithelial tumors Benign Urothelial papilloma Inverted papilloma Squamous cell papilloma Nephrogenic adenoma Villous adenoma Others |

Malignant Urothelial carcinoma Squamous cell carcinoma Adenocarcinoma Small cell carcinoma Undifferentiated carcinoma Others |

Nonepithelial tumors Benign Fibroepithelial polyp Leiomyoma Fibrous histiocytoma Neurofibroma Hemangioma Lipoma Hibernoma |

Malignant Leiomyosarcoma Rhabdomyosarcoma Fibrosarcoma Angiosarcoma Osteosarcoma Malignant peripheral nerve sheath tumor |

Miscellaneous Pheochromocytoma Carcinoid Lymphoma Plasmacytoma Wilms tumor (nephroblastoma) Choriocarcinoma Malignant melanoma |

♦

The incidence of these tumors ranges from 0.6 to 1.1 per 100,000, and there is a male-to-female ratio of 1.7:1 with an increasing incidence in females

♦

Tumors of the ureter and renal pelvis account for 9% of all urinary tract neoplasms and 10–15% of renal tumors

♦

More common in older patients (mean, 70 years)

♦

More than 90% are urothelial carcinomas

♦

Primary nonurothelial carcinomas represent 1.9% of all patients with upper urinary tract tumors

♦

Risk factors include tobacco smoking and occupational exposure (as for urinary bladder carcinoma), as well as additional upper urinary tract risk factors (discussed below)

♦

Hematuria and flank pain are the chief presenting symptoms

Benign Urothelial Neoplasms

♦

Benign epithelial tumors are rare in the upper urinary tract

♦

In this location, most benign epithelial tumors are urothelial papilloma, inverted papilloma, villous adenoma, nephrogenic adenoma, or squamous papilloma

♦

Most lesions are incidental findings and show similar histology to their bladder counterparts

♦

Synchronous inverted papilloma of the urinary bladder and the renal pelvis may occur

Flat Urothelial Lesions with Atypia

♦

Similar lesions to those of the urinary bladder are seen, including urothelial dysplasia, carcinoma in situ, and reactive urothelial atypia

Urothelial Carcinoma

Clinical

♦

Carcinoma arising in the renal pelvis and calyces is twice as common as carcinoma of the ureter

♦

Multifocality is frequent

Often associated with concurrent or metachronous urinary bladder tumors

Synchronous renal cell carcinoma and urothelial carcinoma may coexist

Bilateral synchronous or metachronous ureteral and renal pelvic carcinomas may occur

♦

Etiologic and predisposing factors additional to those of bladder malignancy include phenacetin abuse, papillary necrosis, Balkan nephropathy, thorium-containing radiologic contrast material, urinary tract infections, or nephrolithiasis

♦

Some tumors of the ureter and renal pelvis are associated with hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer syndrome (Lynch syndrome)

♦

Hydronephrosis and stones may be present in renal pelvic tumors, whereas hydroureter and/or stricture may accompany ureteral neoplasms

♦

The most important prognostic factor is tumor stage

In evaluating these specimens, it is important to avoid overstaging as pT3, those tumors that invade the muscularis (pT2) but show extension into renal tubules with a pagetoid or intramucosal pattern

Survival for patients with pTa/pTis lesions is favorable but declines to 75% in patients with pT2 tumors

Survival for patients with pT3 and pT4 tumors, lymph node metastasis, or residual tumor after surgery is poor

Ki-67 and HER2 overexpression might be of prognostic value and predict disease progression and cancer-specific survival

Macroscopic

♦

Tumors may be papillary, polypoid, nodular, ulcerative, or infiltrative (Fig. 37.4)

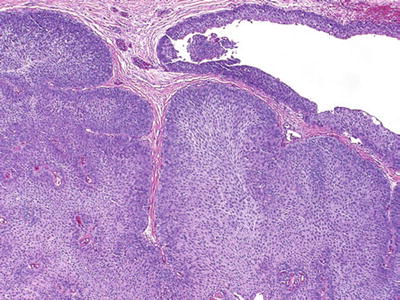

Fig. 37.4.

Papillary urothelial carcinoma of the renal pelvis (left) and the ureter (right).

♦

Some tumors distend the entire renal pelvis while others ulcerate and infiltrate, causing thickening of the wall

♦

A high-grade, invasive tumor may appear as an ill-defined mass that involves the renal parenchyma, mimicking a primary renal cell carcinoma

Microscopic

♦

These tumors mirror bladder urothelial neoplasia and therefore exhibit similar histology including noninvasive papillary carcinoma, invasive carcinoma, and carcinoma in situ

♦

The entire morphologic spectrum of urothelial carcinoma and its variants may be seen

♦

Tumor types include those showing squamous and glandular differentiation, inverted growth (Fig. 37.5), or other morphologic variants (nested, microcystic, micropapillary, lymphoepithelioma-like, clear cell, osteoclast-rich, rhabdoid, and plasmacytoid variants)

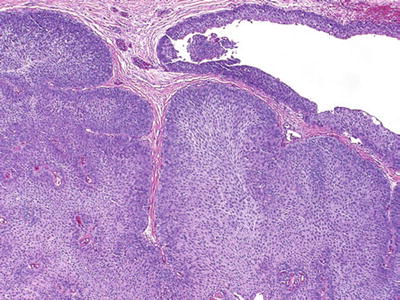

Fig. 37.5.

Urothelial carcinoma with inverted growth.

♦

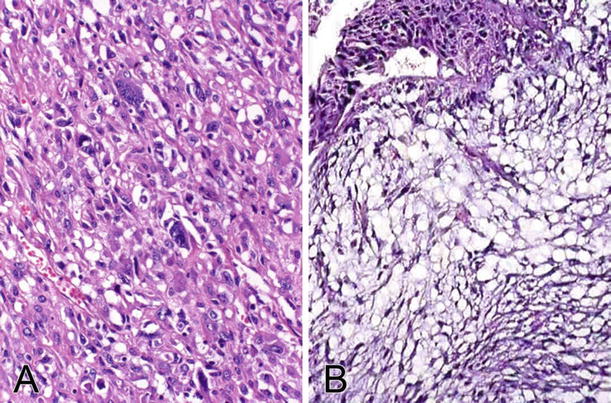

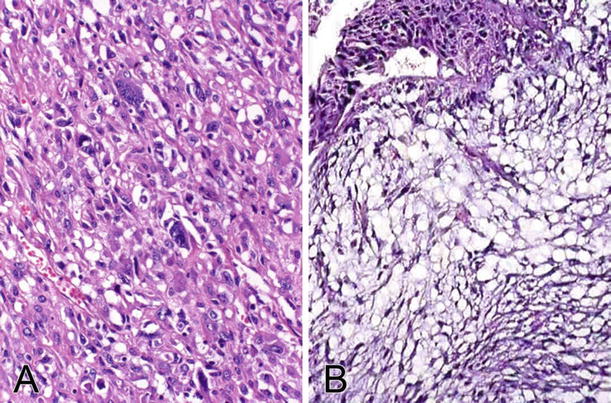

Sarcomatoid carcinoma (Fig. 37.6) is rare in the renal pelvis and ureter, with a poor prognosis, containing either homologous or heterologous elements, often coexpressing keratins, EMA, and vimentin

Fig. 37.6.

Sarcomatoid carcinoma. (A) The tumor is composed of malignant spindle-shaped cells with significant cytologic atypia. The cells are positive for cytokeratin immunostaining. (B) The tumor may have a myxoid appearance (myxoid variant).

♦

Recent data suggest limited diagnostic value for PAX-8 (22% +), GATA3 (11% +), p40 (33% +), and uroplakin III (100% –) in diagnosing sarcomatoid carcinoma of the upper urinary tract

♦

Rare cases of choriocarcinoma reported in this location are thought to represent high-grade urothelial carcinoma with trophoblastic differentiation

Immunohistochemistry

♦

Similar immunoprofile to its counterpart in the bladder

♦

Some urothelial carcinomas in this location display alpha fetoprotein or cyclooxygenase-2 expression

♦

p63 and high molecular weight cytokeratin (34βE12) are positive

♦

Although PAX-2 and PAX-8 are renal tubular markers, positivity for these has been described in upper urinary tract urothelial carcinomas to a greater extent than in urinary bladder tumors

♦

PAX-8+/p63– immunoprofile supports collecting duct carcinoma in the appropriate context, whereas most urothelial carcinomas show the opposite pattern

Molecular

♦

Urothelial carcinomas of the renal pelvis and ureter show molecular similarities to bladder carcinoma

♦

Microsatellite instability (MSI) is more common in upper urinary tract cancers

♦

Deletions on chromosome 9p and 9q may occur in more than one-half of upper urinary tract tumors

♦

Frequent deletions at 17p and TP53 gene mutations are seen in advanced carcinomas

♦

20–30% of all upper urinary tract cancers demonstrate MSI and loss of the mismatch repair proteins MSH2, MLH1, or MSH6

♦

Mutations in the sequences of TGFβ–RII, BAX, MSH3, and MSH6 genes are found in 20–33% of cases with MSI, indicating a molecular pathway of carcinogenesis that is similar to some mismatch repair-deficient colorectal cancers

♦

Tumors with MSI have different clinical and histological features including:

Low tumor stage and grade

Papillary growth

Higher prevalence in female patients

Often an inverted growth pattern

Recent study challenges these clinicopathologic features and shows high-grade prevalence and about equal ratio between genders