8

Chapter Outline

| 1. | Introduction |

| 2. | Billing Models |

| 3. | Other Methods and Models |

| 4. | Chapter Summary |

| 5. | References |

| 6. | Additional Selected References |

| 7. | Web Resources |

| Web Toolkit available at www.ashp.org/ambulatorypractice |

Chapter Objectives

1. Compare and contrast the most common models of billing for ambulatory pharmacist services, including incident-to, facility fee, medication therapy management codes, and employer-sponsored wellness programs.

2. Explain how alternative routes of revenue generation, such as grants, demonstration projects, and relative value units, can be used when creating a pharmacist service.

3. List resources to use when creating a sliding fee scale for self-pay patients.

Introduction

The profession of pharmacy is continuously changing to include delivery of comprehensive clinical, consultative, and educational patient care services. No longer is the profession defined solely by products and dispensing, but instead it is enhanced by collaborative practice that is recognized by 47 states, the Department of Veterans Affairs, and the Indian Health Service.1 Pharmacists, however, are not recognized under Title XVIII of the Social Security Act, thus resulting in lack of reimbursement eligibility under Medicare B due to lack of provider status.2

Historically, pharmacists have lobbied for provider status to create reimbursable services that are self-sustaining in a health system.3 Although provider status recognition has not occurred for Medicare Part B, some progress has resulted in recognition under Medicare Part D, certain Medicaid plans in some states, and some individual third-party payers. Other strategies you may consider for payment include funding programs through indirect reimbursement methods such as “incident-to” billing.

In many instances, you may not be able to create a sustainable clinical practice based solely on the direct and indirect billing. Because of this, other creative reimbursement opportunities have surfaced that allow for supplementation of revenue to continue successful practice expansion. This chapter will address the reimbursement strategies that currently exist, along with other creative opportunities to provide guidance to initiate billing, expand billing, or generate funding opportunities that will allow your practice to succeed.

Billing Models

The gold standard for medical billing is the U.S. government and the Centers of Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS). Although other payers such as commercial payers and state Medicaid may develop and use any model they wish, most use the Medicare billing model as their base. Doing so greatly decreases the billing process burden for providers of medical care and their patients. It is a system that has worked for a number of years. This chapter will focus on Medicare billing rules and processes and note how it may differ in the commercial sector or state Medicaid space. If your organization has a large non-Medicare-insured population, the compliance officer in your organization is responsible for understanding the billing process of the payers with which your organization may contract. This is another good reason for you to get to know your compliance officer.

Medicare Structure

To understand Medicare billing, it helps to understand how Medicare is structured. There are four separate arms of Medicare:

1. Medicare Part A is responsible for the rules, regulations, and reimbursement of all institutional services for Medicare beneficiaries, including hospitals, long-term care facilities, hospice, and some home health services. All Medicare beneficiaries have Medicare Part A benefits.

2. Medicare Part B is responsible for the rules, regulations, and reimbursement for all medically necessary outpatient services. This includes physicians, midlevel practitioners that have Part B provider status, some preventative services, and some home care services. Medicare beneficiaries usually have Medicare Part B, but not everyone does. Those without Social Security benefits or those who opted out of this benefit due to coverage with commercial insurance may not have Part B.

3. Medicare Part C, also called the Medicare Advantage Plan, is a managed care program that a beneficiary may opt to use. It is administered by a variety of commercial payers. Medicare pays a monthly fixed amount for the beneficiary to the private insurer who then manages the care and sets reimbursement for providers. Comparatively, this is a small part of Medicare.

4. Medicare Part D is the prescription benefit plan with which most pharmacists are familiar. This plan is administered by commercial companies that contract with Medicare, referred to as prescription drug plans or PDPs. Medication therapy management (MTM) services are included in the administrative fees that Medicare pays to the PDP.

CMS contracts part of the administrative responsibilities for Medicare Part A and/or Medicare Part B to private insurance companies, called fiscal intermediaries (FIs) or regional carriers. They have two primary functions: reimbursement review and medical coverage review. We will elaborate on the impact they have on ambulatory pharmacy patient care services later on in the chapter.

The majority of patient care pharmacy services that occur in outpatient clinics or independent physicians’ offices are for Medicare beneficiaries and fall under Medicare Part B rules, regulations, and processes for billing. Reimbursement in the Medicare Part B space is called fee for service: in other words, you provide a service and you get paid. You may also run into ambulatory organizations that do business in the managed care arena and contract with Medicare Advantage plans. This model uses a capitated reimbursement method in which the organization receives a monthly set fee to manage the health care of a patient. The organization’s reimbursement is also based on meeting or exceeding certain quality clinical and service benchmarks. As already stated, MTM services for Medicare are administered under Medicare Part D.

Incident-to Billing in a Noninstitutional Ambulatory Setting

Medicare Part B Billing

Since pharmacists are not recognized as Medicare Part B providers, the only method available to bill for the services provided by the pharmacists to Medicare beneficiaries in the outpatient clinic or ambulatory setting is “incident-to” billing. Incident-to billing is an indirect billing mechanism whereby pharmacists provide patient care services under direct supervision of a physician or other approved Medicare Part B provider (defined by Medicare to be a physician, physician assistant, nurse practitioner, clinical nurse specialist, nurse midwife, or clinical psychologist).4 We will use “physician” as the term for this provider throughout the remainder of the chapter when speaking about Medicare Part B incident-to billing, with the understanding that Medicare has recently expanded incident-to to include the list of providers mentioned. Incident-to billing is not just for pharmacists, but for any auxiliary personnel that furnish a necessary service that is under and integral to the service provided by the physician or other approved Medicare Part B provider. Currently, incident-to billing is one of the most common means by which you might bill for clinical services.

In order for pharmacists (or other auxiliary personnel) to bill incident-to the physician, Medicare stipulates that certain criteria must be met (Table 8-1). The patient must be an established patient of the practice; there must be a prior face-to face visit with the physician for the same problem; the service must be medically necessary and be an “integral, although incidental, part of the physician’s professional services”; it must be a service commonly furnished in the physicians’ office and commonly rendered without charge or included in the physician’s bill; and it must be furnished by the physician or auxiliary personnel under the physician’s direct supervision.4–6

| An established patient is defined as a patient initially seen by a physician in your practice within the previous 3 years for the same problems you are going to see the patient. The physician establishes a plan of care for the patient that includes or authorizes your service and must continue to be actively involved in that plan of care.4,5 |

Actively involved means the physician continues to see the patient face-to-face and provides evaluation and management (E&M) services for the identified problem(s). Reviewing or signing the notes of your visit does not constitute active involvement. Although CMS rules do not define specifically how often the patient’s physician must be involved in the ongoing treatment and management of the patient when using the incident-to model, many fiscal intermediaries for CMS have interpreted a “one of three rule.” This interpretation means that for Medicare patients, the physician must see the patient every third visit.

Direct supervision is defined by the CMS as “the physician being present in the office suite and immediately available to provide assistance and direction throughout the time the aide is performing services.”4 There are no Medicare-required qualifications for auxiliary personnel; however, Medicare does state that the auxiliary personnel must be a financial expense to the physician and that reporting of their services should be to the physician.4,7 Usually in the case of the ambulatory pharmacist, they may be employed, leased, or contracted; in essence, the pharmacists have some type of legal relationship to the physician.

This does not necessarily have to translate into salary expenses. In the contract, the financial expense incurred by the physician’s practice may include nonsalary support to the pharmacist, such as providing clerical, nursing, billing, and technical staff support, in addition to providing exam room space, office supplies, and common waiting room space.

Through the incident-to billing model, pharmacists bill for their services incident-to the sanctioned Medicare Part B provider using evaluation and management (E&M) codes (99211-99215) for established patients of the practice. ![]()

| Most if not all FIs or regional carriers of CMS have interpreted the incident-to billing rules, for the noninstitutional arena, to mean pharmacists can only bill at the E&M 99211 level unless a physician physically sees the patient and adequate service documentation supports the higher level. The FI rulings revolve around the fact that pharmacists are not recognized Medicare Part B providers, therefore are not allowed to bill at a level higher than the lowest, 99211, nurse-level visit. |

If the Medicare Part B provider sees the patient with you, the provider must provide adequate attestation on your visit note stating that he or she has seen the patient. An example of such attestation may be as simple as “I have seen and assessed this patient. The patient was discussed with the midlevel provider. I agree with the encounter assessment and plan above.” To find the specifics of your region, we suggest contacting your regional CMS carrier directly. You can find your regional carrier contact at http://www.cms.gov/ContractingGeneralInformation/Downloads/02_ICdirectory.pdf. Reimbursement for these services also varies by region and institution type but may be accessed at https://www.cms.gov/apps/physician-fee-schedule/search/search-criteria.aspx.

These visits should then be appropriately documented in the patient’s medical record. Although there are no CMS requirements for visit documentation of a 99211 visit, your service should be documented in the patient’s medical record in the standards outlined in Chapter 6 to show that the interaction occurred and should contain the names of the supervising physician and person providing the service.

Non-Medicare Billing

For non-Medicare incident-to billing, individual state Medicaid rules and commercial payers may allow a pharmacist to bill higher codes as long as services and documentation support the higher billing (99212-99215). Some clinic administrators and compliance officers within institutions may interpret billing rules from these payers conservatively and follow Medicare regulations for non-Medicare payers too. If your institution allows you to bill at a higher level, adequate documentation must be noted to substantiate the higher bill. When documenting to meet the requirements of a higher-level visit, there are three key portions to include: history, physical exam, and medical decision making. In order to bill at these higher levels, you must address and document at least two of these three key portions. The level of billing would depend on the extent of history, physical exam performed or complexity of medical decision making involved. A comprehensive billing card is provided in Appendix 8-1, listing all the required documentation elements required for the various levels of billing. Pharmacists most commonly bill at levels 99211, 99212, and 99213; however, with appropriate documentation, you may bill higher provided all elements are satisfied. Let us now break down the three key areas one by one and discuss the detailed documentation necessary for each component, based on the level billed.

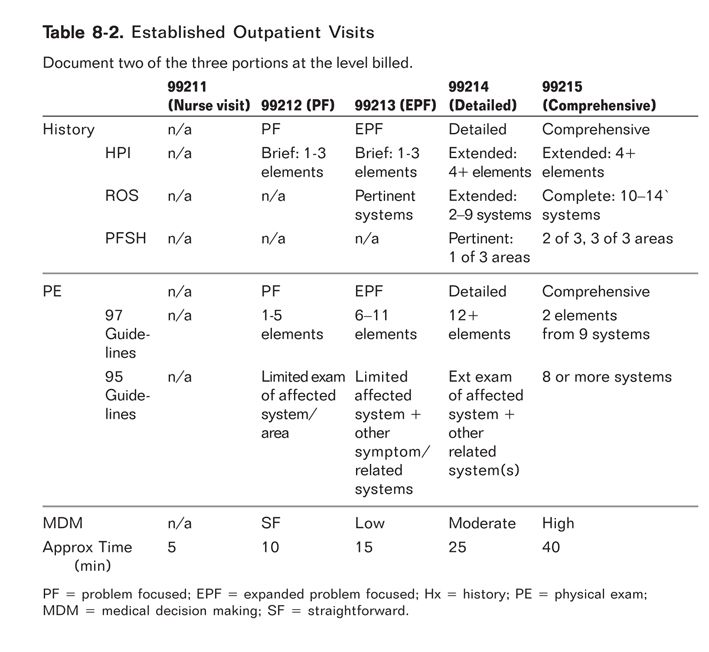

1. | History: The first pertinent area of documentation is the history, which is subcategorized into history of present illness (HPI), including chief complaint for the visit; review of systems (ROS); and past, family, and social history (PFSH). The various elements within the HPI, ROS, and PFSH are included in Appendix 8-1 and Table 8-2.8 The HPI would be considered brief if the documentation includes one to three elements and extended if four or more elements are described or the status of at least three chronic or inactive conditions are noted. |

CASE

You are now an established practitioner seeing patients within Dr. Busybee’s office, and he has referred Ms. Honeybee to you so that you can assist in the management of her uncontrolled diabetes. An example documentation of a history you may create for this diabetic patient at her first appointment is as follows: “Ms. Honeybee is a 56 yo Caucasian female presenting to the office today with a chief complaint of uncontrolled blood sugars. HPI includes 2-week history of polyuria, polydipsia.” If this is a 99214 visit, you may document further to list “elevated glucose readings in the 300s with home monitoring and burning on urination.”

The second area under history is the ROS, which can be broken down into three levels: problem pertinent (1 system), extended (2–9 systems), or complete (at least 10 systems). A problem-pertinent review corresponds to a lower-level visit (99211–99213), an extended review correlates to a 99214 visit, and 10 or more systems constitute a detailed 99215 visit (Table 8-2). The findings of this review may be positive or negative, but each must be documented regardless of its positivity or negativity. If you wish to be more succinct in your documentation of negative findings, “all other systems negative” may be used to indicate a complete ROS was done.8

CASE

The 99213 visit may include focus on the endocrine system, whereas a 99214 visit may go further into documenting blood pressure, lipid labs, etc., as well as the cardiovascular system.

The third and final element of the history is documentation of PFSH. There are two levels to this area of documentation: pertinent (consisting of one of the three areas of past, family, or social history) and complete (for established patients having two of the three areas documented); see Table 8-2.

CASE

A 99213 does not have to contain PFSH, but a 99214 visit would expand to cover at least one element of the PFSH, such as one of the following: a mother with type 2 diabetes mellitus, medication review, or use of tobacco or alcohol.

In summary, there are four levels of billing based on the history component of the visit: problem-focused visit (99212) must contain a brief HPI; an expanded problem-focused visit (99213) must contain a brief HPI and a pertinent ROS, but does not have to contain a PFSH; a detailed visit (99214) must contain an extended HPI (4 or more elements), ROS (2-9 elements), and one PFSH element. A comprehensive visit (99215) must contain an extended HPI, complete ROS (10 or more systems), and documentation of past, family, and social history components (see Table 8-2).

2. | Physical exam: For each level of billing (99212, 99213, etc.) a physical exam is a required element of the visit. The physical exam of the visit may be a general multisystem exam or any single-organ system exam. There are currently two physical exam guidelines that may be used for documentation: the 1995 guidelines and the 1997 guidelines. Both of these are valid; however, the 1995 guidelines are not as detailed and therefore are easier to meet criteria. Table 8-3 and Appendix 8-1 provide the specific elements required for the physical exam for both the 1995 and 1997 guidelines. |

CASE

For Ms. Honeybee, the physical exam would likely include an assessment of the endocrine and genitourinary systems based on her presenting symptoms and thus easily meet the 1995 guidelines for a 99212 or 99213 visit. Depending on the extent of your workup, the visit could reach a 99214 with additional lab workup, reviewing CV system, vitals, etc. A 99214 visit could be reached based on billing with elements in the HPI and MDM, discussed in the next section.

3. | Medical decision making (MDM): Finally, the medical decision-making component is based on the number of diagnostic and/or management options, amount and complexity of data, and risk (Table 8-4). Diagnostic and management options can be scored based on a maximum of 4 points in each of five criteria: |

From: http://www.med.unc.edu/compliance/education-resources-1/RiskTable2.doc

1. self-limited, minor (1 point)

2. established problem stable, improved (1 point)

3. established problem worsening (2 points)

4. new problem, no additional workup planned (3 points)

5. new problem, additional workup planned (4 points)

The amount and complexity of data can be scored on the following: review of clinical lab, radiologic study, or noninvasive diagnostic study (1 point each); discussion of diagnostic study with interpreting physician (1 point); independent review of diagnostic study (2 points); decision to obtain old records or get data from source other than patient (1 point); and review/summarize old medication records or gather data from a source other than the patient (2 points). Risk includes the presenting problem, diagnostic procedures, and management options listed in Table 8-4. Selecting the level of MDM would then be based on cumulative scores in 2 of the 3 above areas (Table 8-2, Appendix 8-1). Other areas that should be documented are amount of time spent providing patient counseling, coordination of care, problem severity, and time spent with the patient.9 If greater than 50% of the visit is spent counseling the patient, one should document the time spent in the visit and note greater than 50% of the face-to-face visit was spent in direct patient counseling. With this notation, time could then be considered the key factor for qualifying the visit for a Current Procedural Terminology (CPT) code.10

CASE

For Ms. Honeybee, you would accrue 4 points based on the fact that she presents with a new problem requiring further workup. You will be reviewing clinical labs. The amount and complexity of data includes the review of those clinical labs and would provide 1 point. The overall risk based on Table 8-4 would be moderate, based on prescription drug management. Therefore, the MDM would be moderate and therefore qualify as a 99214 visit when combined with the other required visit elements discussed above.9

Special Billing Situations

Another option for pharmacist revenue generation has been through the use of G codes.

| There is a separate set of G codes designated for diabetes education for the purpose of teaching patients diabetes self-management and training if you are a certified diabetes educator (CDE). Medicare Part B recognizes CDEs as providers, therefore pharmacists who are CDEs may bill using these codes. Many commercial payers and state Medicaid programs also recognize the CDE codes. These G codes for diabetes education are G0108 for individual visits and G0109 for diabetes education group visits. |

These visits are billed and paid in increments of 30 minutes, with indication of the number of 30-minute increments noted on the billing form. For example, if a diabetes group education class lasts for 240 minutes, you would indicate “G0109 × 8” on the billing form. There must be a signed order from the physician stating the number of initial or follow-up hours needed (maximum of 10 hours per year), topics to be covered in training, and whether the patient should receive individual or group visits. The documentation must be maintained in a file that includes the original order and special instructions. When the order is changed, the new order must also be maintained in the file.11 G codes may be billed in addition to the usual E&M codes if these services are provided in addition to the E&M visit with all the required documentation or alone if those E&M requirements are not met.

In 2005, Medicare began reimbursing for smoking and tobacco use cessation counseling through the use of G codes as well.12 In July 2009, CMS replaced these counseling G codes with CPT codes and clarified that the services could be provided incident-to the physician by qualified personnel as long as proper documentation was provided. Effective January 1, 2011, in addition to CPT codes 99406 and 99407, two G codes, 0436 and 0437, were created for billing tobacco cessation counseling services to prevent tobacco use in nonsymptomatic patients.

|