OBJECTIVES

After studying this chapter, you should be able to:

Describe the elements of the stretch reflex and how the activity of γ-motor neurons alters the response to muscle stretch.

Describe the role of Golgi tendon organs in control of skeletal muscle.

Describe the elements of the withdrawal reflex.

Define spinal shock and describe the initial and long-term changes in spinal reflexes that follow transection of the spinal cord.

Describe how skilled movements are planned and carried out.

Compare the organization of the central pathways involved in the control of axial (posture) and distal (skilled movement, fine motor movements) muscles.

Define decerebrate and decorticate rigidity, and comment on the cause and physiologic significance of each.

Identify the components of the basal ganglia and the pathways that interconnect them, along with the neurotransmitters in each pathway.

Explain the pathophysiology and symptoms of Parkinson disease and Huntington disease.

Discuss the functions of the cerebellum and the neurologic abnormalities produced by diseases of this part of the brain.

INTRODUCTION

Somatic motor activity depends ultimately on the pattern and rate of discharge of the spinal motor neurons and homologous neurons in the motor nuclei of the cranial nerves. These neurons, the final common paths to skeletal muscle, are bombarded by impulses from an immense array of descending pathways, other spinal neurons, and peripheral afferents. Some of these inputs end directly on α-motor neurons, but many exert their effects via interneurons or via γ-motor neurons to the muscle spindles and back through the Ia afferent fibers to the spinal cord. It is the integrated activity of these multiple inputs from spinal, medullary, midbrain, and cortical levels that regulates the posture of the body and makes coordinated movement possible.

The inputs converging on motor neurons have three functions: they bring about voluntary activity, they adjust body posture to provide a stable background for movement, and they coordinate the action of the various muscles to make movements smooth and precise. The patterns of voluntary activity are planned within the brain, and the commands are sent to the muscles primarily via the corticospinal and corticobulbar systems. Posture is continually adjusted not only before but also during movement by information carried in descending brainstem pathways and peripheral afferents. Movement is smoothed and coordinated by the medial and intermediate portions of the cerebellum (spinocerebellum) and its connections. The basal ganglia and the lateral portions of the cerebellum (cerebrocerebellum) are part of a feedback circuit to the premotor and motor cortex that is concerned with planning and organizing voluntary movement.

This chapter considers two types of motor output: reflex (involuntary) and voluntary. A subdivision of reflex responses includes some rhythmic movements such as swallowing, chewing, scratching, and walking, which are largely involuntary but subject to voluntary adjustment and control.

GENERAL PROPERTIES OF REFLEXES

The basic unit of integrated reflex activity is the reflex arc. This arc consists of a sense organ, an afferent neuron, one or more synapses within a central integrating station, an efferent neuron, and an effector. The afferent neurons enter via the dorsal roots or cranial nerves and have their cell bodies in the dorsal root ganglia or in the homologous ganglia of the cranial nerves. The efferent fibers leave via the ventral roots or corresponding motor cranial nerves.

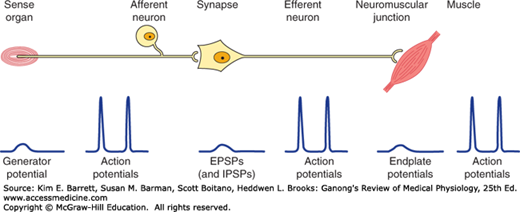

Activity in the reflex arc starts in a sensory receptor with a receptor potential whose magnitude is proportional to the strength of the stimulus (Figure 12–1). This generates all-or-none action potentials in the afferent nerve, the number of action potentials being proportional to the size of the receptor potential. In the central nervous system (CNS), the responses are again graded in terms of excitatory postsynaptic potentials (EPSPs) and inhibitory postsynaptic potentials (IPSPs) at the synaptic junctions. All-or-none responses (action potentials) are generated in the efferent nerve. When these reach the effector, they again set up a graded response. When the effector is smooth muscle, responses summate to produce action potentials in the smooth muscle. In contrast, when the effector is skeletal muscle, the graded response is adequate to produce action potentials that bring about muscle contraction. The connection between the afferent and efferent neurons is in the CNS, and activity in the reflex arc is modified by the multiple inputs converging on the efferent neurons or at any synaptic station within the reflex arc.

FIGURE 12–1

The reflex arc. Note that at the receptor and in the CNS a nonpropagated graded response occurs that is proportional to the magnitude of the stimulus. The response at the neuromuscular junction is also graded, though under normal conditions it is always large enough to produce a response in skeletal muscle. On the other hand, in the portions of the arc specialized for transmission (afferent and efferent nerve fibers, muscle membrane), the responses are all-or-none action potentials.

The stimulus that triggers a reflex is generally very precise. This stimulus is called the adequate stimulus for the particular reflex. A dramatic example is the scratch reflex in the dog. This spinal reflex is adequately stimulated by multiple linear touch stimuli such as those produced by an insect crawling across the skin. The response is vigorous scratching of the area stimulated. If the multiple touch stimuli are widely separated or not in a line, the adequate stimulus is not produced and no scratching occurs. Fleas crawl, but they also jump from place to place. This jumping separates the touch stimuli so that an adequate stimulus for the scratch reflex is not produced.

Reflex activity is stereotyped and specific in that a particular stimulus elicits a particular response. The fact that reflex responses are stereotyped does not exclude the possibility of their being modified by experience. Reflexes are adaptable and can be modified to perform motor tasks and maintain balance. Descending inputs from higher brain regions play an important role in modulating and adapting spinal reflexes.

The α-motor neurons that supply the extrafusal fibers in skeletal muscles are the efferent side of many reflex arcs. All neural influences affecting muscular contraction ultimately funnel through them to the muscles, and they are therefore called the final common pathway. Numerous inputs converge on α-motor neurons. Indeed, the surface of the average motor neuron and its dendrites accommodates about 10,000 synaptic knobs. At least five inputs go from the same spinal segment to a typical spinal motor neuron. In addition to these, there are excitatory and inhibitory inputs, generally relayed via interneurons, from other levels of the spinal cord and multiple long-descending tracts from the brain. All of these pathways converge on and determine the activity in the final common pathways.

MONOSYNAPTIC REFLEXES: THE STRETCH REFLEX

The simplest reflex arc is one with a single synapse between the afferent and efferent neurons, and reflexes occurring in them are called monosynaptic reflexes. Reflex arcs in which interneurons are interposed between the afferent and efferent neurons are called polysynaptic reflexes. There can be anywhere from two to hundreds of synapses in a polysynaptic reflex arc.

When a skeletal muscle with an intact nerve supply is stretched, it contracts. This response is called the stretch reflex or myotatic reflex. The stimulus that initiates this reflex is stretch of the muscle, and the response is contraction of the muscle being stretched. The sense organ is a small encapsulated spindlelike or fusiform-shaped structure called the muscle spindle, located within the fleshy part of the muscle. The impulses originating from the spindle are transmitted to the CNS by fast sensory fibers that pass directly to the motor neurons that supply the same muscle. The neurotransmitter at the central synapse is glutamate. The stretch reflex is the best known and studied monosynaptic reflex and is typified by the knee jerk reflex (Clinical Box 12–1).

CLINICAL BOX 12–1 Knee Jerk Reflex

Tapping the patellar tendon elicits the knee jerk, a stretch reflex of the quadriceps femoris muscle, because the tap on the tendon stretches the muscle. A similar contraction is observed if the quadriceps is stretched manually. Stretch reflexes can be elicited from most of the large muscles of the body. Tapping on the tendon of the triceps brachii, for example, causes an extensor response at the elbow as a result of reflex contraction of the triceps; tapping on the Achilles tendon causes an ankle jerk due to reflex contraction of the gastrocnemius; and tapping on the side of the face causes a stretch reflex in the masseter. The knee jerk reflex is an example of a deep tendon reflex (DTR) in a neurologic exam and is graded on the following scale: 0 (absent), 1+ (hypoactive), 2+ (brisk, normal), 3+ (hyperactive without clonus), 4+ (hyperactive with mild clonus), and 5+ (hyperactive with sustained clonus). Absence of the knee jerk can signify an abnormality anywhere within the reflex arc, including the muscle spindle, the Ia afferent nerve fibers, or the motor neurons to the quadriceps muscle. The most common cause is a peripheral neuropathy from such things as diabetes, alcoholism, and toxins. A hyperactive reflex can signify an interruption of corticospinal and other descending pathways that suppress the activity in the reflex arc.

Each muscle spindle has three essential elements: (1) a group of specialized intrafusal muscle fibers with contractile polar ends and a noncontractile center, (2) large diameter myelinated afferent nerves (types Ia and II) originating in the central portion of the intrafusal fibers, and (3) small diameter myelinated efferent nerves supplying the polar contractile regions of the intrafusal fibers (Figure 12–2A). It is important to understand the relationship of these elements to each other and to the muscle itself to appreciate the role of this sense organ in signaling changes in the length of the muscle in which it is located. Changes in muscle length are associated with changes in joint angle; thus muscle spindles provide information on position (ie, proprioception).

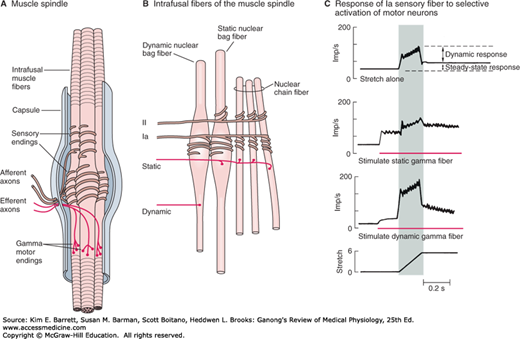

FIGURE 12–2

Mammalian muscle spindle. A) Diagrammatic representation of the main components of mammalian muscle spindle including intrafusal muscle fibers, afferent sensory fiber endings, and efferent motor fibers (γ-motor neurons). B) Three types of intrafusal muscle fibers: dynamic nuclear bag, static nuclear bag, and nuclear chain fibers. A single Ia afferent fiber innervates all three types of fibers to form a primary sensory ending. A group II sensory fiber innervates nuclear chain and static bag fibers to form a secondary sensory ending. Dynamic γ-motor neurons innervate dynamic bag fibers; static γ-motor neurons innervate combinations of chain and static bag fibers. C) Comparison of discharge pattern of Ia afferent activity during stretch alone and during stimulation of static or dynamic γ-motor neurons. Without γ-stimulation, Ia fibers show a small dynamic response to muscle stretch and a modest increase in steady-state firing. When static γ-motor neurons are activated, the steady-state response increases and the dynamic response decreases. When dynamic γ-motor neurons are activated, the dynamic response is markedly increased but the steady-state response gradually returns to its original level. (Reproduced with permission from Gray H: Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 40th ed. St. Louis, MO: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2009.)

The intrafusal fibers are positioned in parallel to the extrafusal fibers (the regular contractile units of the muscle) with the ends of the spindle capsule attached to the tendons at either end of the muscle. Intrafusal fibers do not contribute to the overall contractile force of the muscle, but rather serve a pure sensory function. There are two types of intrafusal fibers in mammalian muscle spindles. The first type contains many nuclei in a dilated central area and is called a nuclear bag fiber (Figure 12–2B). There are two subtypes of nuclear bag fibers, dynamic and static. The second intrafusal fiber type, the nuclear chain fiber, is thinner and shorter and lacks a definite bag. Typically, each muscle spindle contains two or three nuclear bag fibers and about five nuclear chain fibers.

There are two kinds of sensory endings in each spindle, a single primary (group Ia) ending and up to eight secondary (group II) endings (Figure 12–2B). The Ia afferent fiber wraps around the center of the dynamic and static nuclear bag fibers and nuclear chain fibers. Group II sensory fibers are located adjacent to the centers of the static nuclear bag and nuclear chain fibers; these fibers do not innervate the dynamic nuclear bag fibers. Ia afferents are very sensitive to the velocity of the change in muscle length during a stretch (dynamic response); thus they provide information about the speed of movements and allow for quick corrective movements. The steady-state (tonic) activity of group Ia and II afferents provide information on steady-state length of the muscle (static response). The top trace in Figure 12–2C shows the dynamic and static components of activity in a Ia afferent during muscle stretch. Note that they discharge most rapidly while the muscle is being stretched (shaded area of graphs) and less rapidly during sustained stretch.

The spindles have a motor nerve supply of their own. These nerves are 3–6 μm in diameter, constitute about 30% of the fibers in the ventral roots, and are called γ-motor neurons. There are two types of γ-motor neurons: dynamic, which supply the dynamic nuclear bag fibers and static, which supply the static nuclear bag fibers and the nuclear chain fibers. Activation of dynamic γ-motor neurons increases the dynamic sensitivity of the group Ia endings. Activation of the static γ-motor neurons increases the tonic level of activity in both group Ia and II endings, decreases the dynamic sensitivity of group Ia afferents, and can prevent silencing of Ia afferents during muscle stretch (Figure 12–2C).

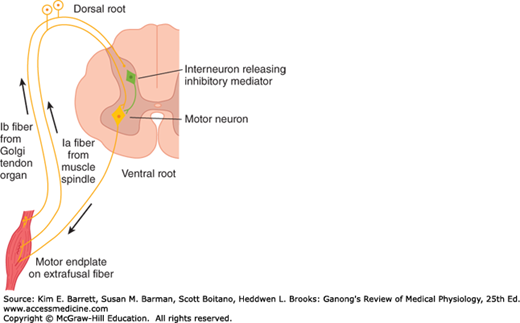

Ia fibers end directly on motor neurons supplying the extrafusal fibers of the same muscle (Figure 12–3). The time between the application of the stimulus and the response is called the reaction time. In humans, the reaction time for a stretch reflex such as the knee jerk is 19–24 ms. Weak stimulation of the sensory nerve from the muscle, known to stimulate only Ia fibers, causes a contractile response with a similar latency. Because the conduction velocities of the afferent and efferent fiber types are known and the distance from the muscle to the spinal cord can be measured, it is possible to calculate how much of the reaction time was taken up by conduction to and from the spinal cord. When this value is subtracted from the reaction time, the remainder, called the central delay, is the time taken for the reflex activity to traverse the spinal cord. The central delay for the knee jerk reflex is 0.6–0.9 ms. Because the minimum synaptic delay is 0.5 ms, only one synapse could have been traversed.

FIGURE 12–3

Diagram illustrating the pathways responsible for the stretch reflex and the inverse stretch reflex. Stretch stimulates the muscle spindle, which activates Ia fibers that excite the motor neuron. Stretch also stimulates the Golgi tendon organ, which activates Ib fibers that excite an interneuron that releases the inhibitory mediator glycine. With strong stretch, the resulting hyperpolarization of the motor neuron is so great that it stops discharging.

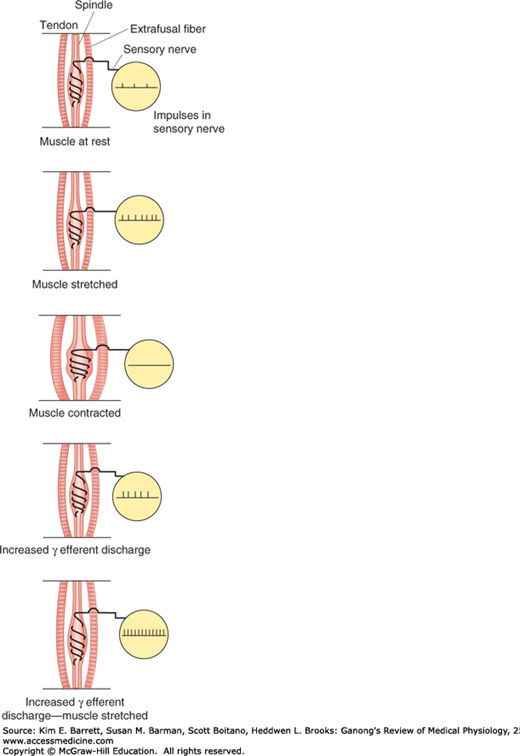

When the muscle spindle is stretched, its sensory endings are distorted and receptor potentials are generated. These in turn set up action potentials in the sensory fibers at a frequency proportional to the degree of stretching. Because the spindle is in parallel with the extrafusal fibers, when the muscle is passively stretched, the spindles are also stretched, referred to as “loading the spindle.” This initiates reflex contraction of the extrafusal fibers in the muscle. On the other hand, the spindle afferents characteristically stop firing when the muscle is made to contract by electrical stimulation of the α-motor neurons to the extrafusal fibers because the muscle shortens while the spindle is unloaded (Figure 12–4).

FIGURE 12–4

Effect of various conditions on muscle spindle discharge. When the whole muscle is stretched, the muscle spindle is also stretched and its sensory endings are activated at a frequency proportional to the degree of stretching (“loading the spindle”). Spindle afferents stop firing when the muscle contracts (“unloading the spindle”). Stimulation of γ-motor neurons cause the contractile ends of the intrafusal fibers to shorten. This stretches the nuclear bag region, initiating impulses in sensory fibers. If the whole muscle is stretched during stimulation of the γ-motor neurons, the rate of discharge in sensory fibers is further increased.

The muscle spindle and its reflex connections constitute a feedback device that operates to maintain muscle length. If the muscle is stretched, spindle discharge increases and reflex shortening is produced. If the muscle is shortened without a change in γ-motor neuron discharge, spindle afferent activity decreases and the muscle relaxes.

Dynamic and static responses of muscle spindle afferents influence physiologic tremor. The response of the Ia sensory fiber endings to the dynamic (phasic) as well as the static events in the muscle is important because the prompt, marked phasic response helps dampen oscillations caused by conduction delays in the feedback loop regulating muscle length. Normally a small oscillation occurs in this feedback loop. This physiologic tremor has low amplitude (barely visible to the naked eye) and a frequency of approximately 10 Hz. Physiologic tremor is a normal phenomenon that affects everyone while maintaining posture or during movements. However, the tremor would be more prominent if it were not for the sensitivity of the spindle to velocity of stretch. It can become exaggerated in some situations such as when we are anxious or tired or because of drug toxicity. Numerous factors contribute to the genesis of physiologic tremor. It is likely dependent on not only central (inferior olive) sources but also peripheral factors including motor unit firing rates, reflexes, and mechanical resonance.

Stimulation of γ-motor neurons produces a very different picture from that produced by stimulation of the α-motor neurons. Stimulation of γ-motor neurons does not lead directly to detectable contraction of the muscles because the intrafusal fibers are not strong enough or plentiful enough to cause shortening. However, stimulation does cause the contractile ends of the intrafusal fibers to shorten and therefore stretches the nuclear bag portion of the spindles, deforming the endings, and initiating impulses in the Ia fibers (Figure 12–4). This in turn can lead to reflex contraction of the muscle. Thus, muscles can be made to contract via stimulation of the α-motor neurons that innervate the extrafusal fibers or the γ-motor neurons that initiate contraction indirectly via the stretch reflex.

If the whole muscle is stretched during stimulation of the γ-motor neurons, the rate of discharge in the Ia fibers is further increased (Figure 12–4). Increased γ-motor neuron activity thus increases spindle sensitivity during stretch.

In response to descending excitatory input to spinal motor circuits, both α- and γ-motor neurons are activated. Because of this “α–γ coactivation,” intrafusal and extrafusal fibers shorten together, and spindle afferent activity can occur throughout the period of muscle contraction. In this way, the spindle remains capable of responding to stretch and reflexively adjusting α-motor neuron discharge.

The γ-motor neurons are regulated to a large degree by descending tracts from a number of areas in the brain that also control α-motor neurons (described below). Via these pathways, the sensitivity of the muscle spindles and hence the threshold of the stretch reflexes in various parts of the body can be adjusted and shifted to meet the needs of postural control.

Other factors also influence γ-motor neuron discharge. Anxiety causes an increased discharge, a fact that probably explains the hyperactive tendon reflexes sometimes seen in anxious patients. In addition, unexpected movement is associated with a greater efferent discharge. Stimulation of the skin, especially by noxious agents, increases γ-motor neuron discharge to ipsilateral flexor muscle spindles while decreasing that to extensors and produces the opposite pattern in the opposite limb. It is well known that trying to pull the hands apart when the flexed fingers are hooked together facilitates the knee jerk reflex (Jendrassik maneuver), and this may also be due to increased γ-motor neuron discharge initiated by afferent impulses from the hands.

When a stretch reflex occurs, the muscles that antagonize the action of the muscle involved (antagonists) relax. This phenomenon is said to be due to reciprocal innervation. Impulses in the Ia fibers from the muscle spindles of the protagonist muscle cause postsynaptic inhibition of the motor neurons to the antagonists. The pathway mediating this effect is bisynaptic. A collateral from each Ia fiber passes in the spinal cord to an inhibitory interneuron that synapses on a motor neuron supplying the antagonist muscles. This example of postsynaptic inhibition is discussed in Chapter 6, and the pathway is illustrated in Figure 6–6.

INVERSE STRETCH REFLEX

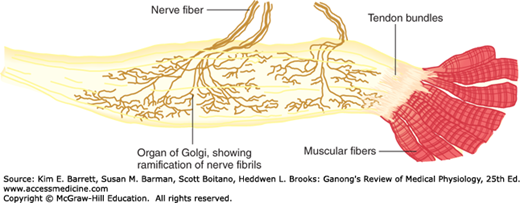

Up to a point, the harder a muscle is stretched, the stronger is the reflex contraction. However, when the tension becomes great enough, contraction suddenly ceases and the muscle relaxes. This relaxation in response to strong stretch is called the inverse stretch reflex. The receptor for the inverse stretch reflex is in the Golgi tendon organ (Figure 12–5). This organ consists of a netlike collection of knobby nerve endings among the fascicles of a tendon. There are 3–25 muscle fibers per tendon organ. The fibers from the Golgi tendon organs make up the Ib group of myelinated, rapidly conducting sensory nerve fibers. Stimulation of these Ib fibers leads to the production of IPSPs on the motor neurons that supply the muscle from which the fibers arise. The Ib fibers end in the spinal cord on inhibitory interneurons that in turn terminate directly on the motor neurons (Figure 12–3). They also make excitatory connections with motor neurons supplying antagonists to the muscle.

FIGURE 12–5

Golgi tendon organ. This organ is the receptor for the inverse stretch reflex and consists of a netlike collection of knobby nerve endings among the fascicles of a tendon. The innervation is the Ib group of myelinated, rapidly conducting sensory nerve fibers. (Reproduced with permission from Gray H: Gray’s Anatomy: The Anatomical Basis of Clinical Practice, 40th ed. St. Louis, MO: Churchill Livingstone/Elsevier; 2009.)

CLINICAL BOX 12–2 Clonus

A characteristic of states in which increased γ-motor neuron discharge is present is clonus. This neurologic sign is the occurrence of regular, repetitive, rhythmic contractions of a muscle subjected to sudden, maintained stretch. Only sustained clonus with five or more beats is considered abnormal. Ankle clonus is a typical example. This is initiated by brisk, maintained dorsiflexion of the foot, and the response is rhythmic plantar flexion at the ankle. The stretch reflex–inverse stretch reflex sequence may contribute to this response. However, it can occur on the basis of synchronized motor neuron discharge without Golgi tendon organ discharge. The spindles of the tested muscle are hyperactive, and the burst of impulses from them discharges all the motor neurons supplying the muscle at once. The consequent muscle contraction stops spindle discharge. However, the stretch has been maintained, and as soon as the muscle relaxes it is again stretched and the spindles stimulated. There are numerous causes of abnormal clonus including traumatic brain injury, brain tumors, strokes, and multiple sclerosis. Clonus may also occur in spinal cord injury that disrupts the descending cortical input to a spinal glycinergic inhibitory interneuron called the Renshaw cell. This cell receives excitatory input from α-motor neurons via axon collaterals (and in turn it inhibits the same α-motor neuron). In addition, cortical fibers activating ankle flexors contact Renshaw cells (as well as type Ia inhibitory interneurons) that inhibit the antagonistic ankle extensors. This circuitry prevents reflex stimulation of the extensors when flexors are active. Therefore, when the descending cortical fibers are damaged (upper motor neuron lesion), the inhibition of antagonists is absent. The result is repetitive, sequential contraction of ankle flexors and extensors (clonus). Clonus may be seen in patients with amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, stroke, multiple sclerosis, spinal cord damage, epilepsy, liver or kidney failure, and hepatic encephalopathy.

THERAPEUTIC HIGHLIGHTSTreatment of clonus often centers on its underlying cause. For some individuals, physical therapy that includes stretching exercises can reduce episodes of clonus. Immunosuppressants (eg, azathioprine and corticosteroids), anticonvulsants (eg, primidone and levetiracetam), and tranquilizers (eg, clonazepam) have been shown to be beneficial in the treatment of clonus. Botulinum toxin has also been used to block the release of acetylcholine in the muscle, which triggers the rhythmic muscle contractions that are characteristic of clonus.

Because the Golgi tendon organs, unlike the spindles, are in series with the muscle fibers, they are stimulated by both passive stretch and active contraction of the muscle. The threshold of the Golgi tendon organs is low. The degree of stimulation by passive stretch is not great because the more elastic muscle fibers take up much of the stretch, and this is why it takes a strong stretch to produce relaxation. However, discharge is regularly produced by contraction of the muscle, and the Golgi tendon organ thus functions as a transducer in a feedback circuit that regulates muscle force in a manner analogous to the spindle feedback circuit that regulates muscle length.

The importance of the primary endings in the spindles and the Golgi tendon organs in regulating the velocity of the muscle contraction, muscle length, and muscle force is illustrated by the fact that section of the afferent nerves to an arm causes the limb to hang loosely in a semiparalyzed state. The interaction of spindle discharge, tendon organ discharge, and reciprocal innervation determines the rate of discharge of α-motor neurons (Clinical Box 12–2).

The resistance of a muscle to stretch is often referred to as its tone or tonus. If the motor nerve to a muscle is severed, the muscle offers very little resistance and is said to be flaccid. A hypertonic (spastic) muscle is one in which the resistance to stretch is high because of hyperactive stretch reflexes. Somewhere between the states of flaccidity and spasticity is the ill-defined area of normal tone. The muscles are generally hypotonic when the rate of γ-motor neuron discharge is low and hypertonic when it is high.

When the muscles are hypertonic, the sequence of moderate stretch → muscle contraction, strong stretch → muscle relaxation is clearly seen. Passive flexion of the elbow, for example, meets immediate resistance as a result of the stretch reflex in the triceps muscle. Further stretch activates the inverse stretch reflex. The resistance to flexion suddenly collapses, and the arm flexes. Continued passive flexion stretches the muscle again, and the sequence may be repeated. This sequence of resistance followed by a sudden decrease in resistance when a limb is moved passively is known as the clasp-knife effect because of its resemblance to the closing of a pocket knife. It is also known as the lengthening reaction because it is the response of a spastic muscle to lengthening.

POLYSYNAPTIC REFLEXES: THE WITHDRAWAL REFLEX

Polysynaptic reflex paths branch in a complex manner. The number of synapses in each of their branches varies. Because of the synaptic delay at each synapse, activity in the branches with fewer synapses reaches the motor neurons first, followed by activity in the longer pathways. This causes prolonged bombardment of the motor neurons from a single stimulus and consequently prolonged responses. Furthermore, some of the branch pathways turn back on themselves, permitting activity to reverberate until it becomes unable to cause a propagated transsynaptic response and dies out. Such reverberating circuits are common in the brain and spinal cord.

The withdrawal reflex is a typical polysynaptic reflex that occurs in response to a noxious stimulus to the skin or subcutaneous tissues and muscle. The response is flexor muscle contraction and inhibition of extensor muscles, so that the body part stimulated is flexed and withdrawn from the stimulus. When a strong stimulus is applied to a limb, the response includes not only flexion and withdrawal of that limb but also extension of the opposite limb. This crossed extensor response is properly part of the withdrawal reflex. Strong stimuli can generate activity in the interneuron pool that spreads to all four extremities. This spread of excitatory impulses up and down the spinal cord to more and more motor neurons is called irradiation of the stimulus, and the increase in the number of active motor units is called recruitment of motor units.

Flexor responses can be produced by innocuous stimulation of the skin or by stretch of the muscle, but strong flexor responses with withdrawal are initiated only by stimuli that are noxious or at least potentially harmful (ie, nociceptive stimuli). The withdrawal reflex serves a protective function as flexion of the stimulated limb gets it away from the source of irritation, and extension of the other limb supports the body. The pattern assumed by all four extremities puts one in position to escape from the offending stimulus. Withdrawal reflexes are prepotent; that is, they preempt the spinal pathways from any other reflex activity taking place at the moment.

Many of the characteristics of polysynaptic reflexes can be demonstrated by studying the withdrawal reflex. A weak noxious stimulus to one foot evokes a minimal flexion response; stronger stimuli produce greater and greater flexion as the stimulus irradiates to more and more of the motor neuron pool supplying the muscles of the limb. Stronger stimuli also cause a more prolonged response. A weak stimulus causes one quick flexion movement; a strong stimulus causes prolonged flexion and sometimes a series of flexion movements. This prolonged response is due to prolonged, repeated firing of the motor neurons. The repeated firing is called after-discharge and is due to continued bombardment of motor neurons by impulses arriving by complicated and circuitous polysynaptic paths.

As the strength of a noxious stimulus is increased, the reaction time is shortened. Spatial and temporal facilitation occurs at synapses in the polysynaptic pathway. Stronger stimuli produce more action potentials per second in the active branches and cause more branches to become active; summation of the EPSPs to the threshold level for action potential generation occurs more rapidly.

Another characteristic of the withdrawal response is the fact that supramaximal stimulation of any of the sensory nerves from a limb never produces as strong a contraction of the flexor muscles as that elicited by direct electrical stimulation of the muscles themselves. This indicates that the afferent inputs fractionate the motor neuron pool; that is, each input goes to only part of the motor neuron pool for the flexors of that particular extremity. On the other hand, if all the sensory inputs are dissected out and stimulated one after the other, the sum of the tension developed by stimulation of each is greater than that produced by direct electrical stimulation of the muscle or stimulation of all inputs at once. This indicates that the various afferent inputs share some of the motor neurons and that occlusion occurs when all inputs are stimulated at once.

SPINAL INTEGRATION OF REFLEXES

The responses of animals and humans to spinal cord injury (SCI) illustrate the integration of reflexes at the spinal level. The deficits seen after SCI vary, of course, depending on the level of the injury. Clinical Box 12–3 provides information on long-term problems related to SCI and recent advancements in treatment options.

CLINICAL BOX 12–3 Spinal Cord Injury

It has been estimated that the worldwide annual incidence of sustaining spinal cord injury (SCI) is between 10 and 83 per million of the population. Leading causes are vehicular accidents, violence, and sports injuries. The mean age of patients who sustain an SCI is 33 years old, and men outnumber women with a nearly 4:1 ratio. Approximately 52% of SCI cases result in quadriplegia and about 42% lead to paraplegia. In quadriplegic persons, the threshold of the withdrawal reflex is very low; even minor noxious stimuli may cause not only prolonged withdrawal of one extremity but marked flexion–extension patterns in the other three limbs. Stretch reflexes are also hyperactive. Afferent stimuli irradiate from one reflex center to another after SCI. When even a relatively minor noxious stimulus is applied to the skin, it may activate autonomic neurons and produce evacuation of the bladder and rectum, sweating, pallor, and blood pressure swings in addition to the withdrawal response. This distressing mass reflex can however sometimes be used to give paraplegic patients a degree of bladder and bowel control. They can be trained to initiate urination and defecation by stroking or pinching their thighs, thus producing an intentional mass reflex. If the cord section is incomplete, the flexor spasms initiated by noxious stimuli can be associated with bursts of pain that are particularly bothersome. They can be treated with considerable success with baclofen, a GABAB receptor agonist that crosses the blood-brain barrier and facilitates inhibition.

THERAPEUTIC HIGHLIGHTSTreatment of SCI patients presents complex problems. Administration of corticosteroids such as methylprednisolone may have beneficial effects by fostering recovery and minimizing loss of function after SCI. They need to be given soon after the injury and then discontinued because of the well-established deleterious effects of long-term corticosteroid treatment. Their immediate value is likely due to reduction of the inflammatory response in the damaged tissue. Because SCI patients are immobile, a negative nitrogen balance develops and large amounts of body protein are catabolized. Their body weight compresses the circulation to the skin over bony prominences, causing formation of pressure ulcers. The ulcers heal poorly and are prone to infection because of body protein depletion. The tissues that are broken down include the protein matrix of bone and this, plus the immobilization, cause Ca2+ to be released in large amounts, leading to hypercalcemia, hypercalciuria, and formation of calcium stones in the urinary tract. The combination of stones and bladder paralysis cause urinary stasis, which predisposes to urinary tract infection, the most common complication of SCI. The search continues for ways to get axons of neurons in the spinal cord to regenerate. Administration of neurotrophins shows some promise in experimental animals, and so does implantation of embryonic stem cells at the site of injury. Another possibility being explored is bypassing the site of SCI with brain-computer interface devices. However, these novel approaches are a long way from routine clinical use.

In all vertebrates, transection of the spinal cord is followed by a period of spinal shock during which all spinal reflex responses are profoundly depressed. Subsequently, reflex responses return and become hyperactive. The duration of spinal shock is proportional to the degree of encephalization of motor function in the various species. In frogs and rats it lasts for minutes; in dogs and cats it lasts for 1–2 h; in monkeys it lasts for days; and in humans it usually lasts for a minimum of 2 weeks.

Cessation of tonic bombardment of spinal neurons by excitatory impulses in descending pathways (see below) undoubtedly plays a role in development of spinal shock. In addition, spinal inhibitory interneurons that normally are themselves inhibited may be released from this descending inhibition to become disinhibited. This, in turn, would inhibit motor neurons. The recovery of reflex excitability may be due to the development of denervation hypersensitivity to the mediators released by the remaining spinal excitatory endings. Another contributing factor may be sprouting of collaterals from existing neurons, with the formation of additional excitatory endings on interneurons and motor neurons.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree