Fig. 9.1

Expulsion time: the levator ani and puborectalis sling are stretched

Fig. 9.2

Introitus aspect in nulliparous and multiparous

A rectocele may also be the end result of chronic straining because of constipation.

Small rectoceles can be found in nulliparous women [2] and most of the time are asymptomatic.

Rectoceles can be classified applying different criteria, for example, according to their position—low, middle or high [3]—and/or their size: small (<2 cm), medium (2–4 cm) or large (>4 cm) [2]. Size is measured anteriorly from a line drawn upward from the anterior wall of the anal canal on proctography. The most useful classification organizes the rectocele and its treatment into three clinical stages at straining during defaecating proctography [4, 5] (Table 9.1).

Table 9.1

Classification of rectoceles

Type I | Digitiform rectocele or single hernia through the rectovaginal septum |

Type II | Lax rectovaginal septum large sacculation |

Anterior rectal mucosal prolapse | |

Deep Douglas pouch | |

Frequently associated with an enterocele | |

Type III | Rectocele associated with invagination and/or prolapse of the rectum frequently associated with an enterocele |

Furthermore, the length of the anal canal seems to play an important role in the development of incontinence and urgency.

If the anal canal on lateral view is symmetric and if the anterior and posterior sides are approximately equal in length, a rectocele may result from chronic constipation or dyschezia. If the anterior part is short resulting in an anal asymmetry, the patient fills the rectocele with stools, and despite a good anterior displacement of the puborectalis sling, it is unable to retain faeces. This results in incomplete exoneration, persistent need to pass stools or even marked incontinence.

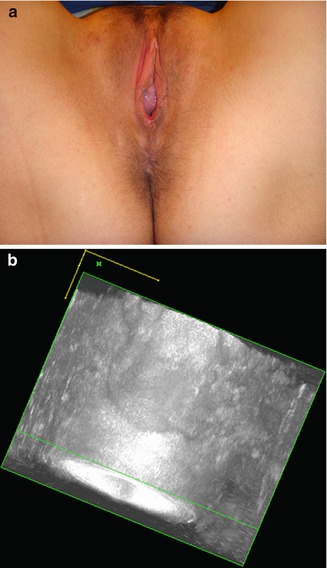

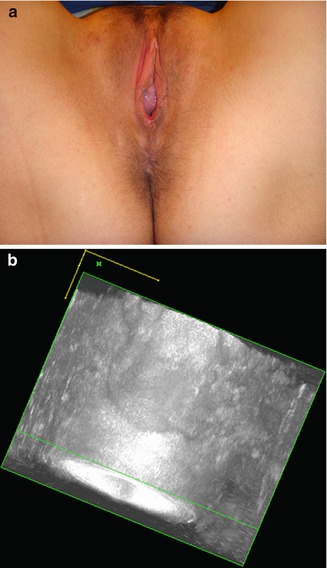

Small rectoceles rarely produce symptoms [6, 7]. Large rectoceles may cause obstructed defaecation, constipation, pain and bleeding due to ulceration [8]. Sometimes they interfere with sexual function. Perineal pressure or vaginal digitation is often described as a measure taken by the patient to help defaecation. Incomplete evacuation of the rectoceles on defaecating proctography is an important finding [5]. In case of major postpartum damage of the perineum, we can observe sphincter lesions, perineal body damage and stretching and/or rupture of the puborectalis. These ruptures can occur at the insertion point of the muscle. Clinically, the patient presents with a deviation of the anus on the healthy side and a large introitus with a wide vagina. One can often demonstrate evidence of puborectalis damage with clinical exam and ultrasound (Fig. 9.3).

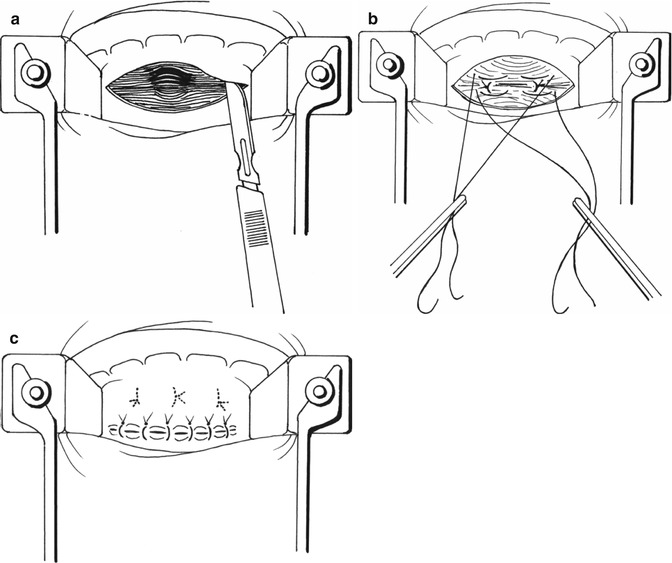

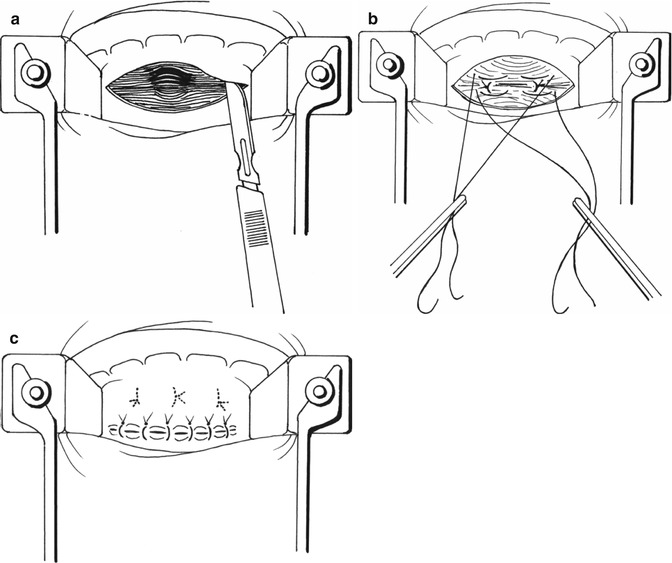

Fig. 9.3

Type I rectocele treatment according Sullivan-Sarles procedure: (a) Incision of anterior rectal mucosa above the dentate line. The rectal wall is exposed to the apex of the rectocele. (b) The rectal muscle is plicated, using a series of vertically placed sutures to reinforce the rectal wall. (c) Redundant mucosa is excised and the defect closed

Treatment

Medical

Once the diagnosis is confirmed, a high-fibre diet (25–35 g/day) plus ingestion of 2–3 l of non-caffeinated, nonalcoholic fluids per day is recommended as initial conservative treatment. Other conservative methods of treatment such as pelvic floor exercises, electrical stimulation of the pelvic floor muscles and the use of supportive devices such as pessaries within the vagina are of limited use [9]. If control of the patient’s symptoms by conservative treatment is suboptimal, the authors will consider surgical therapy.

Surgical

Surgical repair should only be carried out on carefully selected symptomatic patients or in the context of any coexisting pelvic floor abnormality. Surgical indications for a symptomatic rectocele repair include the presence of obstructive defaecation symptoms, lower pelvic pressure and heaviness, prolapse of the posterior vaginal wall, pelvic relaxation or enlarged vaginal hiatus. The best results occur in patients who need to vaginally digitate [10] rather than in those needing to apply pressure to the perineum or digitate rectally [11]. Barium trapping on defaecography is also often used as a selection criterion [12] although it is not felt to be directly associated with defaecatory dysfunction [5]. An abnormal transit study with coexisting constipation might predict a less favourable outcome post rectocele repair [12].

Several approaches have been described to repair rectoceles:

In order to tailor the surgical procedure in accordance with the lesions observed and their functional complications, we have prospectively applied the following policy (Table 9.2):

Table 9.2

Surgical policy in the treatment of rectoceles

Type I | Endorectal repair (Sullivan-Sarles, STARR) | |

+Incontinence | Sullivan-Sarles + transverse plication of internal sphincter | |

Type II | Perineal or vaginal repair | |

+Incontinence | Sphincter repair | |

Type III | Double abdomino-vaginal approach according to Zacharin. |

The surgical treatment should be tailored to correct the type of rectocele, the associated symptoms and any other concomitant pelvic floor disorders.

Type I Digitiform Rectocele or Single Hernia Through the Rectovaginal Septum

Type 1 rectoceles are treated by the endorectal approach, which was described by Sullivan et al. [16] and Sarles et al. [14, 31] and is usually carried out with the patient in the prone jackknife position. We prefer a classic gynaecologic position with the advantage of less anaesthetic risk and a shorter operating room time while the patient position does not need to be changed. The anterior rectal submucosa above the dentate line is infiltrated with a solution of local anaesthetic and a vasoconstrictor. A flap of mucosa is raised off the rectal circular muscle to expose the rectal wall as far as the apex of the rectocele. The rectal muscle is then plicated, using a series of five to eight vertically placed sutures to reinforce the rectal wall. Redundant mucosa is excised and the defect closed [14, 16]. Some surgeons prefer to plicate the muscle with horizontal mattress sutures [10, 32] (Fig. 9.3a–c).

In the presence of an intact but weak sphincter and a short anterior anal canal, the longitudinal plication can be completed by two or three double-V transverse sutures to lengthen the anal canal. This reinforces the occlusion mechanism and improves incontinence.

An anterior Delorme’s procedure has been described as another anal approach to rectoceles, especially with an associated mucosal prolapse [33] or rectal invagination [34].

Endorectal procedures done with mechanical sutures were already described in 1993 by different authors [21, 22].

This likely inspired Longo and partners in the description of the STARR procedure. The stapled transanal rectal resection (STARR) procedure has been proposed for large rectoceles with intrarectal intussusception and a history of obstructed defaecation syndrome. Intrarectal intussusception described on defaecating proctography may suggest a mechanical obstruction to defaecation. Unfortunately, this has never been clearly proven as a direct cause of obstructed defaecation because the proctograms used in demonstrating this theory have always shown an empty rectum; thus intussusception cannot be advocated as the cause of obstruction.

The objectives of the STARR procedure in these patients are:

1.

Removal of the prolapsing rectum and restoration of the normal anatomy

2.

Re-establishing the continuity of the rectal muscular wall in order to regain normal rectal capacity and compliance

3.

Anatomical correction of the rectocele or posterior colpocele

The largest prospective multicentre trial containing 90 patients undergoing the STARR procedure for treatment of outlet obstruction caused by the combination of intussusception and rectocele has shown encouraging early results [35–37]. All patients had significant improvement in constipation symptoms without affecting continence, and postoperative defaecating proctography showed the disappearance of both the intussusception and rectocele [17].

Severe complications, however, have been reported, including bleeding, faecal urgency, incontinence, stenosis, dramatic chronic pain, constipation [38] and rectovaginal and enteral fistulas [39, 40].

In our experience these complications are very difficult to treat. They result in an important negative influence on patient quality of life following treatment of a benign disease. The presence of an entero- or sigmoidocele at rest is a contraindication to the use of this technique.

Type II Large Sacculation of Lax Rectovaginal Septum

Type II rectoceles may be treated by transvaginal or transperineal approaches, with or without the use of prosthetic materials to support the repair.

If a transverse perineal incision is used, the whole of the rectovaginal septum is exposed, separating each structure to demonstrate the levator ani, which is plicated using a series of horizontal mattress sutures. The interposition of mesh at this site has been reported [41]. Major complications such as erosion and infections may occur between 5 and 25 % [42–46]. It has been proposed that this approach is limited as it does not allow enough access to the upper part of the rectovaginal septum and to the pouch of Douglas. However, this approach can be useful in cases with a concomitant sphincter repair.

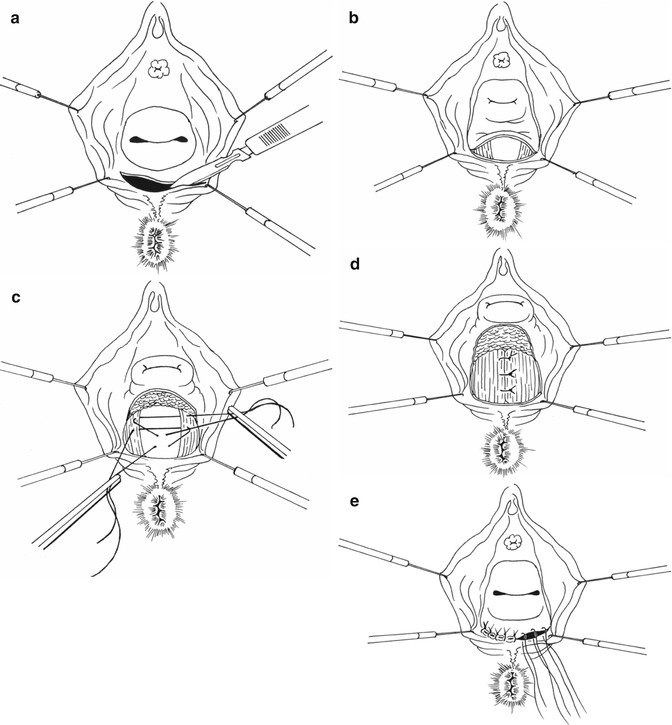

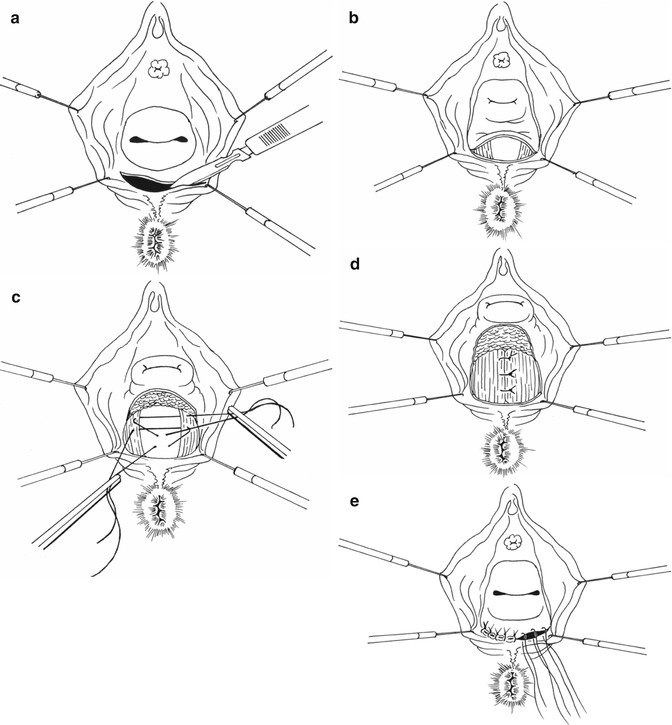

The transvaginal approach with an extensive posterior colpomyorrhaphy is a technique that has traditionally been preferred by gynaecologists and performed in the lithotomy position. A Lone Star retractor is useful, and following local anaesthetic and vasoconstrictor infiltration, the vaginal mucosa is incised transversely at the posterior hymen level and mobilized as far as the cervix or vaginal vault. The peritoneum at this point is mobilized and pushed up, and a Douglasorrhaphy may be performed. The levator ani and puborectalis muscles are dissected out and approximated at the midline with sutures. The first three sutures include the rectal muscle superficially 1–1.5 cm below the level of the first stitch into the puborectalis muscle. The rectal wall is then lifted and an anterior rectal mucosal prolapse is prevented (Fig. 9.4a–e). When the vaginal vault is prolapsing, a sacrospinal fixation may also be added [3, 47, 48]. In these cases, a colpopexy to the sacrospinal ligament may also be carried out.

Fig. 9.4

Type II rectocele treatment. (a) Transversal incision of vaginal mucosa. (b) Dissection of levator ani and puborectalis muscles. (c and d): Levator ani suture with rectal wall pexy at the midline. (e) Closure of vaginal mucosa incision

If there is sphincter rupture or stretching, a sphincteroplasty may also be performed. One should note that an endovaginal approach is necessary in order to repair cases involving a ruptured puborectalis muscle (Fig. 9.5).

Fig. 9.5

(a) Damage of the left puborectalis with deviation of the anus on the healthy side. (b) Damage of the left puborectalis on sonography

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree