Fig. 8.1

Transvaginal scan showing symmetry and no damage to levator plate

As stated before nulliparous women may also develop prolapse, 6.5 % in the Women’s Health Initiative study [1] and the agreed associations above; there is also a clear genetic component as seen in twin studies [11].

Age is a significant risk factor [5]; the prevalence of rectocele is increasing with age from 15 % in the 30–39-year-olds age group to over 20 % in the 40–49-year-old age group and approximately 30 % by the time patients reach the age of 50–59. As previously mentioned, this study also confirms that not only is there an increase in age but prolapse occurs in 44 % of parous women, whereas the corresponding prevalence of amongst non-parous women is 5.8 %. Being overweight confers a significant increase in risk for developing a rectocele by 38 % if BMI is between 25 and 30 and by 75 % when the BMI is >30 [1].

Due to the multifactorial nature of pelvic organ prolapse and the fact that symptomatic rectoceles rarely occur in isolation, it is beholden upon a surgeon to understand which symptoms are most likely to be associated with the rectocele and therefore can be helped by correction of this anatomical abnormality. Patients who present with a rectocele may have a collection of both gynaecological and bowel symptoms as well as often having urinary symptoms too. The bowel symptoms may be constipation; obstructive defaecation (which includes an inability to empty); faecal incontinence, which is often passive or post-defaecatory leakage; pruritus ani; dyspareunia; and symptoms of bulge or pressure. In reality treatment of the rectocele in these patients with defaecatory problems may not only not improve their symptoms but make things worse. A very elegant paper by Pescatori [12] in 2006 described the many symptoms that a patient can suffer from when presenting with a primary problem of obstructive defaecation. He describes an iceberg syndrome, whereby the main presenting symptom may underlie a multitude of many other problems. In his series of 100 consecutive constipated patients with a median age of 52, 54 of the patients had both mucosal prolapse and rectocele. However, 66 of the patients had at least 3 other problems including anxiety, depression, anismus and rectal hyposensation. Other associated problems included vaginal prolapse, neuropathy, enterocele and solitary rectal ulcer. In this series, the majority of patients were treated conservatively, and only 14 underwent any form of surgery. It is therefore important to take an excellent history to exclude or include other diagnoses and problems.

Dietz and Korda [13] in 2005 undertook a prospective study of 505 women presenting with symptoms to a tertiary urogynaecological clinic. They found 64 % of women had a rectocele. They examined the patients using transperineal ultrasound looking for herniation of the anterior anorectal muscularis and mucosa into the vagina. The symptoms strongly associated with posterior compartment descent were incomplete bowel emptying and digitation. Pain, chronic constipation and faecal incontinence were less strongly associated.

Pathophysiology and Anatomy of Rectocele

Although risk factors for POP can be identified, the specific events leading to a development of rectocele are poorly understood. It is likely that damage to a supportive layer of the fascia between the rectum and the vagina occurs. The origin of this fascia is in dispute, and a layer does not exist in isolation but as a component of other connective tissue that envelops the pelvic organs. Histologically the tissue is fibromuscular elastic layer which consists of dense collagen with course elastic fibres, smooth muscles and associated small blood vessels. Delancey’s work [14] has divided this into three separate levels. From a craniocaudal direction, the upper third level or level one blends with the peritoneum of the cul-de-sac, the uterosacral ligaments and the base of the cardinal ligaments. The distal third of the vaginorectum, level 3, fascia blends with the perineum body. This has an important role in supporting the perineum with fascia attachments up to the ischiopubic rami and the urogenital diaphragm. For the middle third, level 2, the rectovaginal fascia extends laterally out to the fascia overlying the levator ani muscles.

The paper by Delancey in 1999 [14] was seminal in helping us understand the support system for the pelvic organs. Understanding these layers is essential to understanding what may go wrong. The support is multifaceted with connective tissue and striated muscles differing at different levels (Fig. 8.2).

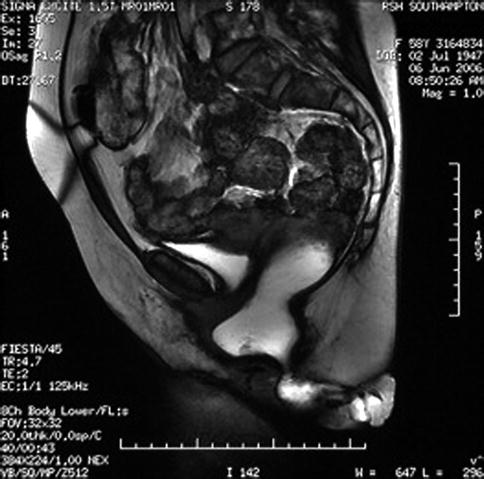

Fig. 8.2

Rectocele and its relation to pelvic organs

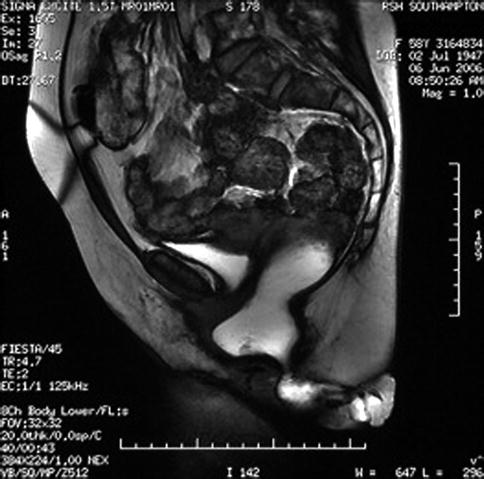

Fig. 8.3

Vaginal scan of perineal body and puborectalis

The pelvic organ support system has an anterior compartment, middle compartment and posterior compartment. The vagina and uterus and endopelvic fascia lie within the middle compartment and attach themselves to the pelvic wall to separate the anterior and posterior compartments. Delancey undertook an extensive anatomical study of 42 fresh and 22 fixed cadavers to look at and define the posterior compartments structural anatomy relevant to rectoceles. The fixed specimens were used to study the overall arrangement of pelvic floor structures; however, the resistance of the posterior vaginal wall was studied in fresh cadavers not affected by fixation. As a result of this study, Delancey describes three different levels of rectum. The distal rectum lies in close apposition to the dense connective tissue of the perineal body at level 3. The perineal body (Fig. 8.3) represents the central connection between the two halves of the perineal membrane; when the distal rectum is subjected to force directed caudally, the fibres of the perineum membrane become tight and resist further displacement. This is necessary for evacuation so that there is substance or support for the waves of propulsion through the rectum to work against. Damage to the perineal body leaves the rectum more freely mobile and allows the distal rectum to prolapse downwards. The connections between the two halves of the perineal membrane extend cranially up from the perineal body for 2–3 cm whilst becoming progressively thinner towards the cranial margin. Above this level is level 2. The supporting structures of the middle portion of the posterior vaginal wall (level 2) are attached on either side of the rectum to the inner surface of the pelvic diaphragm by a sheet of endopelvic fascia. These fascial sheets themselves attach to the posterior lateral vaginal wall producing a posterior vaginal sulcus on each side of the rectum. These endopelvic fascia sheets prevent the ventral movement of the posterior rectal wall.

The upper portion of the posterior vaginal wall (level 1) is attached to the pelvic wall by a sheetlike mesentery of the paracolpium. There are also coexisting muscular actions of the levator ani muscles which give additional support at level 2 and the upper surface of level 3. When these muscles contract, the connective tissue is elevated indicating that all these tissues work together to maintain support. The level 2 support is a balance between the fascia sheets and the muscles especially puborectalis; damage to either of these can result in a lack of vaginal wall support. The lower third is particularly supported by the dense connective tissue of the perineal body.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree