Radical Antegrade Modular Pancreato-Splenectomy (Ramps): Radical Distal Pancreato-Splenectomies for Invasive Malignancies

Steven M. Strasberg

Introduction

Distal pancreato-splenectomy has been performed for invasive malignancy of the body and tail of the pancreas for over 100 years. In the standard procedure, the dissection proceeds from left to right. After division of the short gastric vessels and the splenocolic ligament, the lienorenal ligament is divided and the spleen and distal pancreas are mobilized off retroperitoneal structures. The final steps are division of the splenic vessels and the pancreas proximal to the tumor. As an oncologic procedure, this approach has several serious shortcomings. Positive tangential margin rates are high, especially on the posterior aspect of the dissection. This is partly due to the poor view obtained of the retroperitoneum when dissecting in this direction. The procedure is not based on the lymph node drainage of the pancreas. As a result N1 nodes are frequently left behind and low node resection rates are common. Blood supply is controlled late in the procedure.

In 2003, we described a procedure designed to overcome these shortcomings—radical antegrade modular pancreato-splenectomy (RAMPS). The posterior margin of the dissection is based on preoperative computed tomograms and is always behind the anterior renal fascia, all N1 lymph nodes are harvested, and the dissection is carried right to left, thereby allowing early vascular control. The posterior margin may be anterior to the adrenal gland (anterior RAMPS) or posterior to it (posterior RAMPS) depending on the proximity of the tumor to the adrenal gland and other structures in the perinephric space, but it is always posterior to the anterior renal fascia. In 2007, we presented results showing that this technique is capable of attaining very high negative tangential margin rates. The purpose of this chapter is to present the rationale and technique of this procedure. We will also briefly describe the technique for extending radical pancreato-splenectomy when the tumor invades the celiac artery—the Appleby operation, although at present this technique does not have proven efficacy.

Rationale of the Ramps Procedure

Tangential Margins

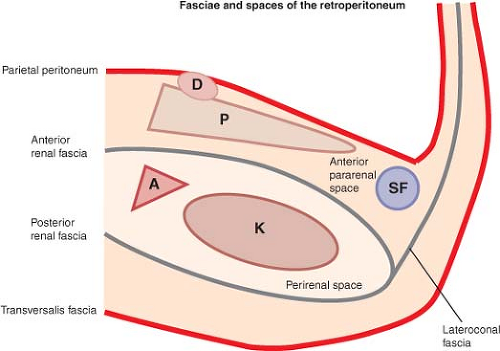

A working knowledge of the surgical anatomy of the pancreas and surrounding structures including fascial layers and anatomic spaces is key to performance of rational oncologic surgery for tumors of the body and tail of the pancreas. Because of the central position of the kidneys in this anatomy, the fasciae and spaces are named in relation to these paired organs (Fig. 1). Since this chapter deals with tumors of the body and tail of the pancreas, this description is confined to left-sided structures.

The left kidney and adrenal gland and their draining veins lie in a space delineated by the anterior and the posterior renal fasciae (Fig. 1). Within this “perirenal” space (“peri” means around), the structures and organs are enclosed within loose fat with little fibrous tissue. Laterally, the anterior and posterior renal fasciae fuse to form the lateroconal fascia (Fig. 1). The pancreatic body and tail, the duodenum, the root of the mesocolon, and the splenic flexure lie in the anterior pararenal space (“para” means near or adjacent in reference to the kidney), between the anterior renal fascia and the posterior parietal peritoneum (Fig. 1). The organs in this space are surrounded by a denser connective tissue, especially medially around the superior mesenteric artery, the celiac artery, and their branches. The anterior renal fascia is a very important layer for the pancreatic surgeon. Dissection on the posterior margin of the pancreas as is done in the conventional pancreato-splenectomy is anterior to this fascia. Dissection on the adrenal vein and gland as is done in the anterior RAMPS procedure is posterior to the anterior renal fascia and removes it.

The body and tail of the pancreas lies obliquely across the retroperitoneum, oriented so that the tail lies at a more superior position than the neck. Because it is relatively thin and narrow, there is little room for malignant tumors to grow within

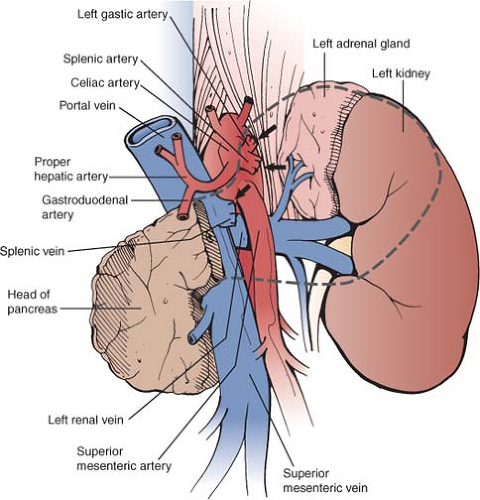

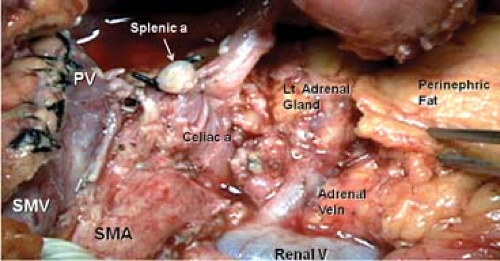

this part of the pancreas, and penetration of the pancreatic capsule with invasion of surrounding structures is common. Also because of its long course, it contacts or lies in proximity to several organs and major blood vessels, all of which may be invaded by pancreatic tumors. Anteriorly, the stomach is the organ that is most commonly invaded since the posterior parietal peritoneum is usually in contact with the visceral peritoneum covering the posterior wall of the stomach. Laterally, the spleen is frequently involved by tail lesions. The structures that share the pararenal space with the pancreas on its inferior aspect include the root of the mesocolon, the duodenum, and the splenic flexure of the colon more laterally. These, especially the root of the mesocolon, which may also partly lie posterior to the pancreas can be invaded by pancreatic tumors. The posterior relationships of the pancreas (Fig. 2) are the most important to the surgeon since positive margins after resection occur most commonly on the posterior margin. Posteriorly, pancreatic tumors invade the splenic artery, the celiac artery and sometimes the origin of the left gastric artery as well as the superior mesenteric artery, aorta, the splenic vein, and the confluence of the splenic and superior mesenteric veins. They also invade posteriorly through the anterior renal fascia to involve the adrenal and less commonly the kidney or the vasculature of these organs.

this part of the pancreas, and penetration of the pancreatic capsule with invasion of surrounding structures is common. Also because of its long course, it contacts or lies in proximity to several organs and major blood vessels, all of which may be invaded by pancreatic tumors. Anteriorly, the stomach is the organ that is most commonly invaded since the posterior parietal peritoneum is usually in contact with the visceral peritoneum covering the posterior wall of the stomach. Laterally, the spleen is frequently involved by tail lesions. The structures that share the pararenal space with the pancreas on its inferior aspect include the root of the mesocolon, the duodenum, and the splenic flexure of the colon more laterally. These, especially the root of the mesocolon, which may also partly lie posterior to the pancreas can be invaded by pancreatic tumors. The posterior relationships of the pancreas (Fig. 2) are the most important to the surgeon since positive margins after resection occur most commonly on the posterior margin. Posteriorly, pancreatic tumors invade the splenic artery, the celiac artery and sometimes the origin of the left gastric artery as well as the superior mesenteric artery, aorta, the splenic vein, and the confluence of the splenic and superior mesenteric veins. They also invade posteriorly through the anterior renal fascia to involve the adrenal and less commonly the kidney or the vasculature of these organs.

RAMPS deals with the problem of the posterior tangential margin by tailoring the operation to the position of the tumor, but the posterior plane of dissection is always set behind the anterior renal fascia. To set the depth of the operation—anterior versus posterior RAMPS—recent preoperative fine-cut contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) scans are used to determine the posterior extent of the tumor. For tumors that have not penetrated the posterior capsule of the pancreas, the dissection is carried out on a plane just posterior to the anterior renal fascia on the anterior surface of the left adrenal gland and anterior to the perinephric fat (Fig. 3). For tumors that have penetrated the posterior capsule, the dissection is carried out on a plane posterior to the left adrenal gland and on the anterior surface of the kidney behind the perinephric fat (Fig. 4). Note that when dissecting from right to left as in RAMPS, the plane of dissection is also sloped anterior to posterior as opposed to posterior to anterior in the standard method. As a result, visualization is much improved. Thus, RAMPS establishes where the posterior

plane of dissection should lie and provides a method to determine that plane in individual patients.

plane of dissection should lie and provides a method to determine that plane in individual patients.

Lymph Nodes

Two methods of investigation, “anatomical” and “pathological,” have been used to determine the pattern of lymph node metastases of cancers arising from specific sites. Anatomical investigations are directed toward determining the normal lymph node drainage from organs and tissues. Dissection and injection of markers are used to identify the primary and secondary nodal drainage stations from particular organs or parts of organs. Pathological lymph node mapping studies use resection or autopsy specimens from patients with particular tumors. The nodes are dissected out of the specimens, examined for the presence of cancer, and the likelihood that the tumor will metastasize to particular nodes is determined. For cancer of the body and tail of the pancreas, only the anatomical type of study has been done. O’Morchoe performed a classic review of this subject.

For RAMPS, the salient points are illustrated schematically in Figure 5. The body and tail of the pancreas has four almost equally sized quadrants: left superior, left inferior, right superior, and right inferior. There are lymphatic intercommunications between the four areas. Lymphatic vessels travelling from the four quadrants (Fig. 5–large arrows) gather on the surface and flow to larger lymphatics lying along the superior and inferior borders of the body and tail of the pancreas. The larger lymphatics course along named blood vessels.

The lymphatics on the superior and inferior borders of the left half of the body and tail drain to the splenic nodes in the hilum of the spleen or gastrosplenic nodes in the gastrosplenic omentum. The lymphatics on the superior and inferior borders of the right half of the body and tail drain to the right. Superiorly, they connect to nodes along the superior border of the body and neck of pancreas as far as the gastroduodenal nodes. The inferior right lymphatics drain to the infrapancreatic (Fig. 5).

The four sets of nodes (splenic, gastrosplenic, gastroduodenal, and infrapancreatic) form a ring of nodes around the body and tail of the pancreas. A second important group of nodes (Fig. 5 “string of nodes”) lies anterior to the aorta in relation to the celiac and superior mesenteric arteries and from slightly above the celiac artery down to and along the superior mesenteric artery for a short distance. This second group of nodes does receive lymph drainage from the nodes of the ring; however, they are not exclusively a second echelon of nodes, that is, N2 nodes. Lymphatic vessels from the pancreas, especially from the more medial aspect of the body of the pancreas may enter them directly without first entering a node on the ring. Therefore, they should be considered to N1 as well as N2 nodes. Based on this information, an operation designed to consistently remove N1 nodes should remove all nodes in the ring, the celiac lymph nodes, and the nodes along the front and left side of the superior mesenteric artery. RAMPS is designed to do that.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree