Rectal Cancer in the 21St Century—Radical Operations: Anterior Resection and Abdominoperineal Excision

R. J. Heald

Introduction

Since the first chapter of “Mastery” was written, it is surprising how much has changed and how much the author still believes should change further. Rectal cancer is overwhelmingly a disease where surgical detail decides outcomes, but surgeons spend their time in ORs and the world has become “multidisciplinary”—often without the wholehearted involvement of surgeons. Multidisciplinary team (MDT) management should be welcomed and the use of preoperative staging by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and of chemoradiotherapy in selected cases are certainly major steps forward. There is little evidence, however, of a major survival benefit from radiation and clear evidence that fertility is abolished, sexual function impaired, and bowel function often grossly damaged by the combination of a low anastomosis with radiation—especially when given postoperatively. MRI can show clearly which patients really need RT, namely, those with threatened margins and others with a poor possibility of survival (e.g., N2 disease, extramural large vein invasion on MRI). There is much to be gained by more selectivity by the preoperative MDT meeting.

The surgery itself presents many new and exciting possibilities. Total mesorectal excision (TME) remains the key objective—can it, however, be achieved as well or better by laparoscopy? Or by the Da Vinci Robot? When truly necessary, can the poor results so often obtained by the “standard” APE be improved upon by superior access, for example, the Kocher Holm position face down with excision of the coccyx?

Repeatedly, the story of progress in this field is of better visualization and more precise dissection, improved hemostasis and less collateral damage by diathermy (e.g., the use of traverse monopolar and ligature bipolar electricity). Gradually, surgeons performing open, laparoscopic, and robotic procedures are learning to recognize all the components of the autonomic nervous system of the pelvis. Indeed, they are rewriting the anatomy books as surgical technology advances. A great part of human happiness and dignity depends on the preservation of these crucial nerves. In this chapter, the author has tried to set down the steps that can contribute both to reducing unnecessary damage to them and to ensuring optimal

cure rates by the delivery of more perfect specimens.

cure rates by the delivery of more perfect specimens.

There are few branches of surgery where care and effort in the craft of surgery yield so much benefit to our patients.

Basic Principles

The implications of decisions made in rectal cancer management are grave indeed—cure of cancer, local control of one of Nature’s cruelest malignancies, the necessity for a permanent stoma, the preservation of sexual function, and much more. Decisions regarding both radiotherapy and chemotherapy now present major challenges in a field of ever-increasing complexity, so that multidisciplinary discussion must constantly be recognized by the true long-term consequences for the patient.

We must recognize that, even at its most scientific, surgery is primarily a craft with very special challenges and rewards for excellence. Surgery is not amenable to study by the same methods as those applicable to drugs or medicines or to measurable interventions such as irradiation, yet surgical technique has by far the greatest impact on rectal cancer outcomes. The randomized controlled clinical trial has so far contributed remarkably little to the development of surgical techniques because, particularly in the difficult and complex surgery of cancer, “the devil is in the details.” As a basic principle of any cancer operation, however, the block of tissue to be removed should be precisely defined and subjected to scrutiny. Thus, surgical anatomy and histopathologic audit should become exact sciences in their own right and surgical practice refined to include meaningful judgment on the oncologic quality of the specimen by an independent pathologist after every surgical excision. It is rewarding to report that, since the first edition of this book, naked eye evaluation of the excised specimen has become mandatory in Germany. My own teaching workshops always emphasize the importance of “specimen-orientated surgeons,” that is, surgeons whose first priority during the procedure is the quality of the fascial covered untorn envelope of tissue that he will extract and which constitutes an optimal TME specimen.

Historical Considerations

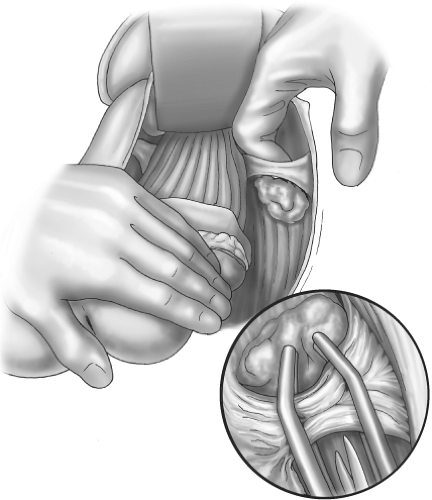

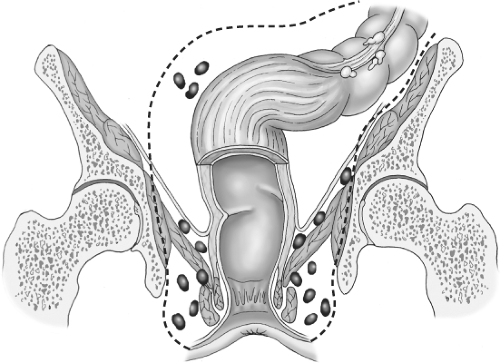

Most of the literature in the Western world has paid scant attention to detail of how the actual dissection around a rectal tumor should be carried out. The diagrams in current textbooks bear witness to the crude manual extraction techniques that bedevil “conventional” surgery for rectal cancer (Fig. 1). However, both the Japanese with their special interest in the detailed vascular and neuroanatomy of the pelvis, and we, with our TME initiative, have attempted to improve on the simplistic concept of abdominoperineal excision (APE), an operation originally described in 1907 by the Englishman Ernest Miles. His concept of a cylinder of maximal size that “empties the whole pelvis” was at least an attempt at defining in advance a block of tissue to be excised by the surgeon. This idea, illustrated in Figure 2, has dominated the minds of doctors throughout the twentieth century. Indeed, if surgeons had really produced perfect “oncologic cylinders,” there would have been far fewer local recurrences and failures, though the morbidity in terms of sexual and pelvic autonomic function would have been formidable while the dead space would have required packing for many months. The famous John Golligher used to comment, “If you haven’t made the patient impotent, you probably haven’t cured him of rectal cancer.”

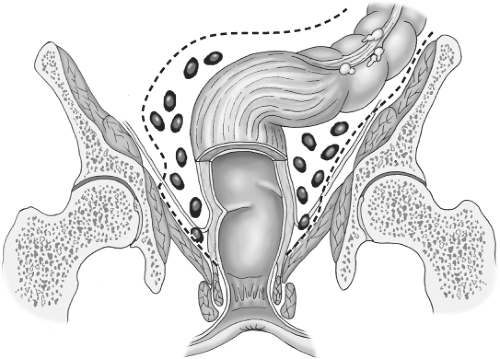

Miles considered that spread occurred, particularly in the lymphatics, in all directions and included very clearly in his diagrams his perception of why he had seen 31 perineal recurrences in the wound of his operations (Figs. 2 and 3). He believed that the reason for these was that he had failed to encompass by his operation, the spread that had occurred into the ischioanal fat via nodes around the inferior hemorrhoidal (rectal) vessels. The same diagram also shows many nodes sitting on the surface of the levator muscles within the imagined “cylinder” of spread. He clearly also believed that, for this reason, only the widest possible clearance at this level had any hope of curing the patient and it was commonplace for tumors as high as 15 to 25 cm to suffer the same fate. So it was that permanent colostomy became established as the necessary price for cure and became a very common and widely dreaded association of bowel cancer in the public mind. Similar thought processes about spread govern most extended surgical lymphadenectomies, but careful studies of ischioanal fossa node involvement to justify this heavy price have never been undertaken. Furthermore, long surgical experience teaches us that multiple nodes on the surface of the levators or in the ischiorectal fat such as those in the diagram are simply never seen.

Such studies were certainly not attempted by Miles, who simply regarded the whole of the surrounding cylinder of tissue as “highly dangerous tissues,” particularly,

“the levators, the ischioanal fat, and the perianal skin.”

“the levators, the ischioanal fat, and the perianal skin.”

Redefinition of Miles’ “Highly Dangerous Tissues”

So it is that the background to our current attempts to move toward an optimal cancer operation is a standard but empirical procedure designed more than a century ago. Virtually, no detail of how the actual dissection should be effected appears in the literature. The Miles’ operation was certainly radical in the sense that it appeared in the diagrams to remove the cancer with much of the surrounding tissue. It was also an operation that could be completed at great speed—often in less than an hour. In the early years of the last century, such speed often meant the difference between a live patient and a dead one at the end of the operation! However, the term “radical” refers to radix, a root in Latin. Leave part of the root and the plant regrows. In cancer terms, this implies a need for real understanding of where the satellites of cancer commonly occur since the ideal radical cancer operation should encompass only the common fields of spread that do not exact too high a penalty from the patient. The design of the optimal operation that modern surgery can now offer should take into account the field of spread amenable to surgical removal with the primary tumor, the disabilities inflicted by each component of the surgery, and the point in time at which cure becomes impossible by local surgery because metastases have already become established.

The first major steps toward minimizing mutilation can be attributed to many surgeons who embarked upon anterior resection (AR) to avoid sacrifice of the anal sphincters. Initiated on both sides of the Atlantic, before and after World War II, the proportion of rectal cancers undergoing sphincter-preserving surgery has risen steadily to a current level of 90% in specialized units and above 50% in most general hospitals.

Modern rational surgical planning should consider each of the possible fields of spread of rectal cancer in turn, and the disabilities and sacrifices paid by the patient for their removal. In each case, we should, to give the patient what we would wish for ourselves, try to balance the benefit of an extra chance of cure against the functional and anatomic price to be paid. At the time of going to press, this implies that preoperative assessment should supplement full clinical and endoscopic appraisal with a computed tomography (CT) scan of the whole body for metastatic spread and a specialized MRI for the most precise picture of the primary cancer and its locoregional spread.

(MRI) scan for appraisal of the primary cancer within the pelvis.

The Embryological Basis of Cancer Surgery—Exemplified By Colorectal Cancer

Recent Advances in Understanding

Conceptually, TME has a basis in scientific thought, which is attractive to all members of the modern multidisciplinary team with background training in basic science. The theory behind it is that cancer spread will tend, initially at least, to remain within the

embryologic hindgut “envelope.” The gut spent its early fetal existence actually outside the abdomen. When secondarily rectum and mesorectum became “plastered” back onto the retroperitoneal structures and into the developing pelvis, they retained their midline lymphovascular integrity and remained separate from the surrounding paired organs and parietes. Their adherence to them is by a collagenous cobweb of areolar tissue, which allows a degree of movement, is recognizable by the surgeon as a “surgical dissection plane” at about the 10-mm stage, and is almost entirely avascular. In a number of publications, the author has drawn attention to this “holy plane of rectal surgery” and attempted to point out the value of painstakingly following the perimesorectal avascular plane around the midline hindgut into the depths of the pelvis as a practical surgical policy. This was eventually shown to improve local recurrence rates in a dramatic way. Straying into the field of cancer spread within the mesorectum was, and still is, in conventional practice, an extremely common cause of involved surgical margins and residual pelvic disease: straying out can damage the autonomic nerve layers and is a common cause of impotence. Publications from the Karolinska Hospital, Solna, Sweden, demonstrate that even more than one half of all local recurrences referred these for investigation are associated with residues of mesorectum left behind by the surgeon. In other words, inadequate TME, that is, incomplete emptying of the central compartment (within the nerve layer) is a far more important course of failure than ignoring the internal iliac and other compartments outside the visceral mesorectal “core.” This is of great practical importance because, although a challenging dissection, TME is a standard teachable reproducible operation. The lateral compartments are much more varied and difficult, and much less rewarding—perhaps best left to a few high-volume specialist surgeons along with other procedures such as sacretomy extended because of threatened margins or secondary nodal spread.

embryologic hindgut “envelope.” The gut spent its early fetal existence actually outside the abdomen. When secondarily rectum and mesorectum became “plastered” back onto the retroperitoneal structures and into the developing pelvis, they retained their midline lymphovascular integrity and remained separate from the surrounding paired organs and parietes. Their adherence to them is by a collagenous cobweb of areolar tissue, which allows a degree of movement, is recognizable by the surgeon as a “surgical dissection plane” at about the 10-mm stage, and is almost entirely avascular. In a number of publications, the author has drawn attention to this “holy plane of rectal surgery” and attempted to point out the value of painstakingly following the perimesorectal avascular plane around the midline hindgut into the depths of the pelvis as a practical surgical policy. This was eventually shown to improve local recurrence rates in a dramatic way. Straying into the field of cancer spread within the mesorectum was, and still is, in conventional practice, an extremely common cause of involved surgical margins and residual pelvic disease: straying out can damage the autonomic nerve layers and is a common cause of impotence. Publications from the Karolinska Hospital, Solna, Sweden, demonstrate that even more than one half of all local recurrences referred these for investigation are associated with residues of mesorectum left behind by the surgeon. In other words, inadequate TME, that is, incomplete emptying of the central compartment (within the nerve layer) is a far more important course of failure than ignoring the internal iliac and other compartments outside the visceral mesorectal “core.” This is of great practical importance because, although a challenging dissection, TME is a standard teachable reproducible operation. The lateral compartments are much more varied and difficult, and much less rewarding—perhaps best left to a few high-volume specialist surgeons along with other procedures such as sacretomy extended because of threatened margins or secondary nodal spread.

Some workers in the past postulated a physical barrier to the spread of cancer at this interface that I call the “holy plane”: it seems intrinsically more probable, in the light of Judah Folkman’s work, that tumor angiogenesis is impeded by the avascular nature of the areolar interface between midline hindgut and surrounding parietes. So it is that embryology is the true key to defining the oncologic package that will encompass the relevant field of spread. The surgeon should bear in mind that the tapering hindgut “package,” surrounded by the “holy plane,” is inserted into the funnel-shaped sloping levators, which merge with the parietal voluntary skeletal external sphincters distally.

The Mesorectum for the Surgeon—the Planes of the Pelvis

Surgical Anatomy

The original idea of TME was born from the practice of surgery. The mesorectum only becomes a reality for each individual surgeon from enthusiasm for slow, meticulous, painstaking dissection in difficult but achievable planes. These, once recognized and identified, become the defining objectives of the surgery and the redefined building blocks of the anatomy.

Once the surgeon has grasped the new system of anatomy, as Stelzner originally did from his diagram, it also becomes clear that the basis for the planes does indeed lie in the embryology (Fig. 4).

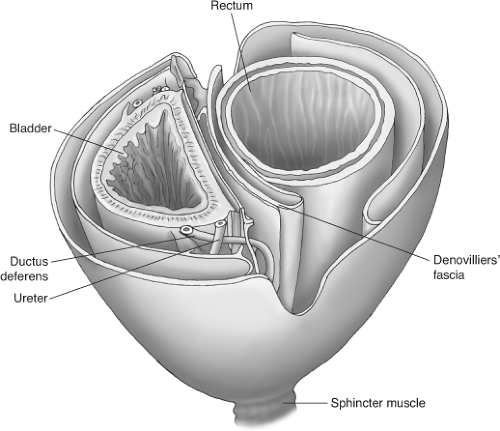

The innermost “holy plane” is that which surrounds the midline hindgut within its lymphovascular envelope—the core—while the two surrounding lamellae comprise a neural layer and a wolffian ridge layer, which develop from the paired structures outside the hindgut. This concept has been made relatively simple to comprehend by the Japanese suggestion of comparing pelvic anatomy with the layers of an onion.

Fig. 4. The fascial layers of the pelvis (after Stelzner). “Like the layers of an onion—or two onions with Denonvilliers septum between.” |

Much of surgery of the whole gastrointestinal tract is a question of pursuing the planes between embryologically separate lymphovascular entities. The careful and thoughtful surgeon who is mobilizing any part of the large intestine by sharp dissection becomes aware of a choice of two relatively avascular, and therefore surgically satisfying planes, which are of special value in his or her journey down into the pelvis. The innermost “holy plane” envelopes the integral visceral mesentery of the hindgut or “mesorectum.” This “safety margin” is a complete fatty and lymphovascular surrounding on all aspects in the middle third of the rectum, which constitutes the greater part of the organ and the commonest site for cancer. In the upper third, the anterior aspect is covered only by the peritoneum with “mesorectum” at the back and the sides as the peritoneal reflection tapers forward toward the “cul-de-sac” or recto-vesical pouch. In the lower third of the rectum, little or no fatty tissue intervenes between the anterior aspect of the rectum and the back of the prostate. Posteriorly, the prostate has an important posterior condensed fascial covering called Denonvilliers septum. The surgeon has to divide this layer from above to enter the plane between the rectum and the prostate in the male. The upper part of the septum

is usually adherent to the anterior mesorectal fat of the middle third. In the female, the middle third has a rather thin and tenuous fatty layer between the rectum and vagina with Denonvilliers fascia being often scant and difficult to identify, certainly a recognizable condensed “septum” is often not found as in the male. Is this perhaps because of its dissolution during childbirth or sexual activity? I use the term “Denonvilliers septum” to describe the shiny anterior surface of the excised middle third of the specimen and its distal continuation to fuse with the back of the prostate (Figs. 2 and 3). This seems logical because Denonvilliers septum is recognized by some embryologists as the downward prolongation of the peritoneum, which has become distally obliterated as a cavity. Fritsch has preferred to call it the “rectogenital septum,” which certainly conveys the reality of a substantial rectangular or trapezoidal layer—like a “bib” between hindgut behind and vesicles and prostate in front. Just as peritoneum is the integral surface of the anterior aspect of the upper intraperitoneal third of the rectum, Denonvilliers septum is integral to the fatty anterior mesorectum in the middle third in the male. Denonvillier was one of the great French surgeon anatomists who described anatomical concepts of importance to surgeons—how far ahead of his time he was! It is only now that improved vision in open surgery and the amazing magnification available to the robotic surgeon that his description of “two layers” of his septum begins to become apparent during operations on the live human. It is now clear to surgeons that, in the human male at least, the trapezoidal “bib” with defined lateral margins just medial to the all important neurovascular bundles is indeed a reality.

is usually adherent to the anterior mesorectal fat of the middle third. In the female, the middle third has a rather thin and tenuous fatty layer between the rectum and vagina with Denonvilliers fascia being often scant and difficult to identify, certainly a recognizable condensed “septum” is often not found as in the male. Is this perhaps because of its dissolution during childbirth or sexual activity? I use the term “Denonvilliers septum” to describe the shiny anterior surface of the excised middle third of the specimen and its distal continuation to fuse with the back of the prostate (Figs. 2 and 3). This seems logical because Denonvilliers septum is recognized by some embryologists as the downward prolongation of the peritoneum, which has become distally obliterated as a cavity. Fritsch has preferred to call it the “rectogenital septum,” which certainly conveys the reality of a substantial rectangular or trapezoidal layer—like a “bib” between hindgut behind and vesicles and prostate in front. Just as peritoneum is the integral surface of the anterior aspect of the upper intraperitoneal third of the rectum, Denonvilliers septum is integral to the fatty anterior mesorectum in the middle third in the male. Denonvillier was one of the great French surgeon anatomists who described anatomical concepts of importance to surgeons—how far ahead of his time he was! It is only now that improved vision in open surgery and the amazing magnification available to the robotic surgeon that his description of “two layers” of his septum begins to become apparent during operations on the live human. It is now clear to surgeons that, in the human male at least, the trapezoidal “bib” with defined lateral margins just medial to the all important neurovascular bundles is indeed a reality.

Posteriorly and posterolaterally, the areolar plane is well defined around the globular expanding bilobed mesorectum. A condensation of the fascia called the rectosacral ligament or Waldeyer’s fascia often presents a barrier to the surgeon posteriorly below the promontory. It is essential that this be positively divided either with diathermy or scissors. Beyond it, the plane is easy to recognize except that the forward angulation demands strong anterodistal retraction to facilitate direct visualization. Understanding the importance of this forward augulation is critical to mastering the traction and counter-traction instruments, necessary in open, laparoscopic, and robotic TME. Confusingly, the middle third of the rectum is often called the horizontal segment because MRIs are typically viewed as if the patient is vertical.

Audit of the Mesorectum By the Pathologist

For proper independent audit, the surgeon should not cut the specimen except to open the bowel away from the tumor to let in the fixation liquid. The pathologist Quirke identified that there is a high positive predictive value of circumferential margin involvement (CMI) for the subsequent development of locally recurrent cancer. This implies that completeness and intactness of the specimen are crucial factors—ideally that it should be one recognizable block of tissue whose orientation and former relations can be identified. While “specimen-orientated surgery” has become the established practice in our unit, recognition of the features of the TME specimen and the freedom of its margins from cancer involvement become the key factor of audit. In most cases, naked-eye inspection provides the initial necessary quality control, with microscopic examination of the suspected areas of margin involvement as a logical primary objective for the surgeon. Visual inspection of the front of a well-performed TME specimen should show three clear landmarks (Fig. 5):

The cut edge of the peritoneal reflection (Fig. 5)

The smooth shiny anterior surface of the anterior mesorectum of the middle third—Denonvilliers fascia—or the rectogenital septum

The almost bare anterior aspect of the anorectal muscle—in the lowest anterior resections or APE specimens only

Laterally, the fatty mesorectum expands distally beyond an anteroposterior groove made by the nerve erigentes so that an embryologically perfect specimen has a lateral dilatation distally, corresponding with the part related to the inside of the levator muscles beyond their origins from the pelvic sidewall. Posteriorly, a perfect specimen exhibits perfectly curved “buttocks” with a central midline groove corresponding to the anococcygeal raphe (the pubococcygeus muscle)—the most posterior of the levator muscle bundles.

Multidisciplinary Team Management

Modern Imaging—Fine-Slice High-Resolution Mri

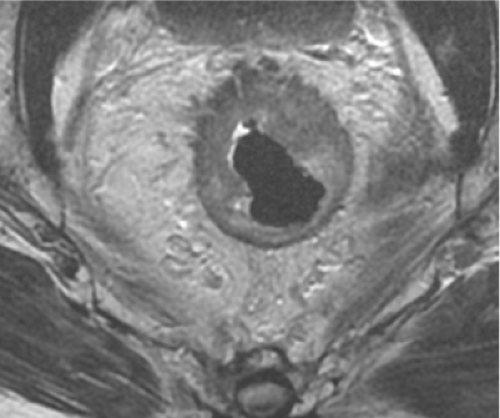

The great step forward of the new millennium is the establishment by Brown, Blomquist, and others that specialized fine-slice high-resolution MRI can visualize this “holy plane” before the surgery and thus predict the detail of the oncologic specimen that the surgeon endeavors to remove, its probable contours, and their relationship to the tentacles of tumor. TME principles are now more readily comprehended by nonsurgeons in the MDT because of the development by these specialist MRI radiologists of images that are far superior to anything previously achievable. The fine-slice high-resolution methods are demonstrably superior to any x-ray-based modality, which inevitably suffers limitations in differentiating tumor tissue from muscle wall. MRI demonstrates, for the first time, the contours of the mesorectum and the distribution of the cancer within it. The recent “Mercury” study from the Pelican Center in Basingstoke has demonstrated reliable equivalence between MRI prediction and histopathologic reality (Fig. 4). It also demonstrates that a 1-mm mesorectal “clearance” does indeed predict a

“safe margin,” provided the surgeon is faithfully following the “holy plane.”

“safe margin,” provided the surgeon is faithfully following the “holy plane.”

Lymph Nodes Close to the Margin

The pelican Mercury Study showed that extramural vascular invasion was an even more important prognostic indicator than nodal involvement at the N1 level. We therefore take this as an indication for giving preoperative CRT.

Conversely, nodal “threats” by proximity to margin did not appear to lead to local recurrence (0/63). This almost certainly reflects the extra care taken by the surgeon to keep clear of such a node by the surgeon who is thus forewarned by the MRI.

This clearance on MRI between cancer within and mesorectal fascia without can be reliably used to predict the need for neoadjuvant “downstaging.” Also, it can warn the surgeon when the mesorectal margin is in danger of being breached during surgery. It can thus provide a “workshop guide” for the detailed surgery, whether this can be performed laparoscopically or open. This may become particularly crucial as a “route map” for laparoscopic surgeons as they increasingly extend their dissections into the challenging depths of the true pelvis where the inability to feel the cancer can be a serious disadvantage. We emphasize the importance of displaying MRIs in the OR during the actual surgery, and the robot might well be adjusted to show them within the console during the operation.

Critical Mri Decisions in Lower-Third Cancers

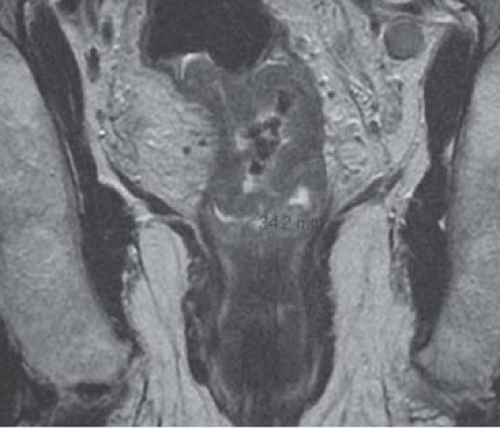

One focal area of current controversy centers on the anatomic and embryologic fact that the mesorectal envelope tapers down in this (infralevator) lower third to appear very thin indeed—particularly on the crucial coronal oblique MRI cuts on which decisions in modern MDTs are made (Fig. 6). On such an MRI it is extremely tempting to predict that this tapering and narrowing area of the mesorectum will constitute a hazardous margin; thus, a decision may be made to administer preoperative downstaging neoadjuvant therapy or even choose APE for fear of margin involvement, when in fact, a carefully orientated axial oblique sequence with the axial cuts precisely at right angles to the tumor segment may demonstrate a potentially safe clearance. Figure 7 shows anterior black “excrescences” of extramural venous cancer spread. In such cases, where the cancer is below the levator origins on MRI, it is essential that an experienced surgeon examines the patient to establish free mobility of the in when the conscious patient (with muscle tone). In the author’s opinion, this clinical observation on the sphincter complex and adjacent organs does almost invariably mean that a TME will be an achievable surgical objective. It does not confront the other tendentious issue of the higher incidence of internal iliac and particularly obturator node involvement in tumors <4 cm from the anal margin.

MDT management is now mandatory for all major malignancies in the UK and is increasingly a standard practice in many institutions throughout the world. The focal point of the decision-making process is becoming the MRI images, which can be readily understood by all, but the surgeon must always have the last word. Nevertheless, the idea that the decision to do an AR or APE is finally made in the OR is disappearing fast. It is wise to have the patient’s permission but the conscientious modern surgeon and MDT will almost always have decided ahead of time.

Fig. 7. Axial magnetic resonance imaging of anterior cancer with EMVI extending close to but just 1 mm clear of the anterior mesorectal margin. |

Summary of the Multidisciplinary Team Sequence

The TME concept can now be extended to embrace a multidisciplinary six-stage process. It is essential that each case is discussed at two meetings: (a) before the operation for overall planning and (b) after receipt of the histopathology reports—for reasons of audit quality control, follow-up, and further adjuvant therapy.

Preoperative. Mdt 1

Clinical

CT to exclude metastatic disease and comorbidity. Various sequences, especially including coronal obliques in the long axis of the anal canal (for low rectal tumors) and fine slice (3 mm) axial obliques at right angles to the tumor segment to assess margins (Fig. 1).

Phased-array-coil fine-slice MRI, no endorectal coil—no bowel preparation.

MDT planning.

Preoperative neoadjuvant therapy in cases selected on the basis of preoperative MRI staging of the pelvis plus whole-trunk CT for the detection of metastases.

Postoperative Review of Patient Recovery Specimen and Histology. Mdt 2

Detailed precision surgery—TME or “TME plus.” “TME minus” or “partial TME” for upper one-third cancers implies that the mesorectum is divided 5 cm below the tumor and a rectal and mesorectal remnant remain—in the interests of creating a “smaller” operation with no temporary stoma.

Detailed audit of the specimen after removal with special emphasis on naked-eye assessment of mesorectal integrity and microscopic evaluation of the margins.

MDT assessment and decision regarding postoperative therapy.

The Surgery

Surgery TME for the surgeon comprises six basic principles:

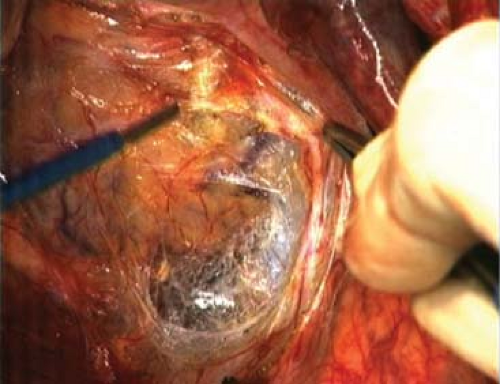

Perimesorectal “holy plane” sharp dissection by monopolar diathermy and scissors under direct vision. Three-directional traction and countertraction is a vital principle for diathermy dissection as it is essential that the areolar tissue be “on stretch” if “holy plane” dissection is to be accurate (Fig. 8).

“Specimen-orientated” surgery and histopathology, of which the object is an intact mesorectum with no tearing of the surface and no CMI—naked eye or microscopic.

Personal naked-eye assessment as audit for obvious CMI as the principal immediate outcome measure. Combined with objective assessment of the whole specimen by the pathologist, this confirms the optimal planning and execution of the surgery. Surgeons and oncologists may also base postoperative therapy on this pathology report, though these must always be a sense of the “horse having bolted” if cancer has been exposed and CRT had not been given before surgery. This was a failure of either planning or surgical technique.

Recognition during surgery of, and preservation of, the autonomic plexuses and nerves, on which sexual and bladder function depend.

A major increase in anal preservation and reduction in the number of permanent colostomies by skilful extension into the depths of the pelvis.

Stapled low pelvic reconstruction, usually using the Moran triple stapling technique, plus creation of a short colon pouch or a side to end anastomosis to low rectum or anal canal.

Before the Operation—Bimanual Pelvic Examination

CT scans and colonoscopy report should always be at hand in the operating room. Never commence surgery without having examined the patient digitally when awake plus performing bimanual examination under anesthesia. This is especially true in the female, so as to establish whether the tumor is fully mobile on the posterior vaginal wall. MRI may already have demonstrated invasion but it is still of value to confirm it. The decision as to whether to excise a part of the posterior wall is finally made at this time by a combination of rectal and vaginal examination, and the latter must never be omitted. Sometimes, if anterior resection is possible, a disc of the posterior wall may be circumscribed around an area of tethering using the angled-point diathermy from below. This is often best performed before the abdominal dissection is started. Routine excision of the posterior vaginal wall is not usually necessary unless it is actually involved.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree