To prevent further tearing of the mucous membranes and infection, never suction or pass a nasogastric tube through the patient’s nose. Observe the patient for signs and symptoms of meningitis, such as a fever and nuchal rigidity, and expect to administer a prophylactic antibiotic.

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as skull X-ray and, possibly, a computed tomography scan. If the dural tear doesn’t heal spontaneously, contrast cisternography may be performed to locate the tear, possibly followed by corrective surgery.

Patient Counseling

Explain which signs and symptoms of neurologic deterioration the patient should report and which activity limitations he needs. Instruct the patient on how to care for a scalp wound.

Pediatric Pointers

Raccoon eyes in children are usually caused by a basilar skull fracture after a fall.

Reference

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Rebound Tenderness[Blumberg’s sign]

A reliable indicator of peritonitis, rebound tenderness is intense, elicited abdominal pain caused by rebound of palpated tissue. The tenderness may be localized, as in an abscess, or generalized, as in perforation of an intra-abdominal organ. Rebound tenderness usually occurs with abdominal pain, tenderness, and rigidity. When a patient has sudden, severe abdominal pain, this symptom is usually elicited to detect peritoneal inflammation.

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting Rebound Tenderness

EXAMINATION TIP Eliciting Rebound Tenderness

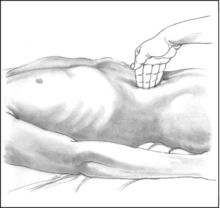

To elicit rebound tenderness, help the patient into a supine position with his knees flexed to relax the abdominal muscles. Push your fingers deeply and steadily into his abdomen (as shown). Then, quickly release the pressure. Pain that results from the rebound of palpated tissue — rebound tenderness — indicates peritoneal inflammation or peritonitis.

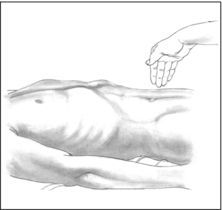

You can also elicit this symptom on a miniature scale by percussing the patient’s abdomen lightly and indirectly (as shown). Better still, simply ask the patient to cough. This allows you to elicit rebound tenderness without having to touch the patient’s abdomen and may also increase his cooperation because he won’t associate exacerbation of his pain with your actions.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you elicit rebound tenderness in a patient who’s experiencing constant, severe abdominal pain, quickly take his vital signs. Insert a large-bore I.V. catheter, and begin administering I.V. fluids. Also, insert an indwelling urinary catheter, and monitor intake and output. Give supplemental oxygen as needed, and continue to monitor the patient for signs of shock, such as hypotension and tachycardia.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition permits, ask him to describe the events that led up to the tenderness. Does movement, exertion, or another activity relieve or aggravate the tenderness? Also, ask about other signs and symptoms, such as nausea and vomiting, a fever, or abdominal bloating or distention. Inspect the abdomen for distention, visible peristaltic waves, and scars. Then, auscultate for bowel sounds and characterize their motility. Palpate for associated rigidity or guarding, and percuss the abdomen, noting tympany. (See Eliciting Rebound Tenderness, page 628.)

Medical Causes

- Peritonitis. With peritonitis, a life-threatening disorder, rebound tenderness is accompanied by sudden and severe abdominal pain, which may be either diffuse or localized. Because movement worsens the patient’s pain, he usually lies still on his back with his knees flexed. Typically, he displays weakness, pallor, excessive sweating, and cold skin. He may also display hypoactive or absent bowel sounds; tachypnea; nausea and vomiting; abdominal distention, rigidity, and guarding; positive psoas and obturator signs; and a fever of 103°F (39.4°C) or higher. Inflammation of the diaphragmatic peritoneum may cause shoulder pain and hiccups.

Special Considerations

Promote comfort by having the patient flex his knees or assume semi-Fowler’s position. If administering an analgesic, keep in mind that it could mask associated symptoms. You may also administer an antiemetic and an antipyretic. However, because of decreased intestinal motility and the probability that the patient will have surgery, don’t give oral drugs or fluids. Obtain samples of blood, urine, and feces for laboratory testing, and prepare the patient for chest and abdominal X-rays, sonograms, and computed tomography scans. Perform a rectal or pelvic examination. Prepare the patient to receive an antibiotic. Have a nasogastric tube inserted to maintain the patient’s nothing-by-mouth status and to allow him to receive continuous parenteral fluid or nutrition.

Patient Counseling

Explain signs and symptoms the patient needs to report immediately and teach him about postoperative care.

Pediatric Pointers

Eliciting rebound tenderness may be difficult in a young child. Be alert for such clues as an anguished facial expression or intensified crying. When you elicit this symptom, use assessment techniques that produce minimal tenderness. For example, have the child hop or jump to allow tissue to rebound gently, and watch as the child clutches at the furniture in pain.

Geriatric Pointers

Rebound tenderness may be diminished or absent in elderly patients.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Rectal Pain

A common symptom of anorectal disorders, rectal pain is discomfort that arises in the anorectal area. Although the anal canal is separated from the rest of the rectum by the internal sphincter, the patient may refer to all local pain as rectal pain.

Because the mucocutaneous border of the anal canal and the perianal skin contains somatic nerve fibers, lesions in this area are especially painful. This pain may result from or be aggravated by diarrhea, constipation, or passage of hardened stools. It may also be aggravated by intense pruritus and continued scratching associated with drainage of mucus, blood, or fecal matter that irritates the skin and nerve endings.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient reports rectal pain, inspect the area for bleeding; abnormal drainage, such as pus; or protrusions, such as skin tags or thrombosed hemorrhoids. Also, check for inflammation and other lesions. A rectal examination may be necessary.

After the examination, proceed with your evaluation by taking the patient’s history. Ask him to describe the pain. Is it sharp or dull, burning or knifelike? How often does it occur? Ask if the pain is worse during or immediately after defecation. Does the patient avoid having bowel movements because of anticipated pain? Find out what alleviates the pain.

Make sure to ask appropriate questions about the development of associated signs and symptoms. For example, does the patient experience bleeding along with rectal pain? If so, find out how frequently this occurs and whether the blood appears on the toilet tissue, on the surface of the stool, or in the toilet bowl. Is the blood bright or dark red? Also, ask whether the patient has noticed other drainage, such as mucus or pus, and whether he’s experiencing constipation or diarrhea. Ask when he last had a bowel movement. Obtain a dietary history.

Medical Causes

- Abscess (perirectal). A perirectal abscess can occur in various locations in the rectum and anus, causing pain in the perianal area. Typically, a superficial abscess produces constant, throbbing local pain that’s exacerbated by sitting or walking. The local pain associated with a deeper abscess may begin insidiously, commonly high in the rectum or even in the lower abdomen, and is accompanied by an indurated anal mass. The patient may also develop associated signs and symptoms, such as a fever, malaise, anal swelling and inflammation, purulent drainage, and local tenderness.

- Anal fissure. An anal fissure is a longitudinal crack in the anal lining that causes sharp rectal pain on defecation. The patient typically experiences a burning sensation and gnawing pain that can continue up to 4 hours after defecation. Fear of provoking this pain may lead to acute constipation. The patient may also develop anal pruritus and extreme tenderness and may report finding spots of blood on the toilet tissue after defecation.

- Anorectal fistula. Pain develops when a tract formed between the anal canal and skin temporarily seals. It persists until drainage resumes. Other chief complaints include pruritus and drainage of pus, blood, mucus, and, occasionally, stool.

- Hemorrhoids. Thrombosed or prolapsed hemorrhoids cause rectal pain that may worsen during defecation and abate after it. The patient’s fear of provoking the pain may lead to constipation. Usually, rectal pain is accompanied by severe itching. Internal hemorrhoids may also produce mild, intermittent bleeding that characteristically occurs as spotting on the toilet tissue or on the stool surface. External hemorrhoids are visible outside the anal sphincter.

Special Considerations

Apply analgesic ointment or suppositories, and administer a stool softener if needed. If the rectal pain results from prolapsed hemorrhoids, apply cold compresses to help shrink protruding hemorrhoids, prevent thrombosis, and reduce pain. If the patient’s condition permits, place him in Trendelenburg’s position with his buttocks elevated to further relieve pain.

You may have to prepare the patient for an anoscopic examination and proctosigmoidoscopy to determine the cause of rectal pain. He may also need to provide a stool sample. Because the patient may feel embarrassed by treatments and diagnostic tests involving the rectum, provide emotional support and as much privacy as possible.

Patient Counseling

Instruct the patient on ways to relieve discomfort. Also, discuss the importance of a proper diet and fluid intake and the need for stool softeners.

Pediatric Pointers

Observe children with rectal pain for associated bleeding, drainage, and signs of infection (a fever and irritability). Acute anal fissure is a common cause of rectal pain and bleeding in children, whose fear of provoking the pain may lead to constipation. Infants who seem to have pain on defecation should be evaluated for congenital anomalies of the rectum. Consider the possibility of sexual abuse in all children who complain of rectal pain.

Geriatric Pointers

Because elderly people typically underreport their symptoms and have an increased risk of neoplastic disorders, they should always be thoroughly evaluated.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C.D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Respirations, Shallow

Respirations are shallow when a diminished volume of air enters the lungs during inspiration. In an effort to obtain enough air, the patient with shallow respirations usually breathes at an accelerated rate. However, as he tires or as his muscles weaken, this compensatory increase in respirations diminishes, leading to inadequate gas exchange and such signs as dyspnea, cyanosis, confusion, agitation, loss of consciousness, and tachycardia.

Shallow respirations may develop suddenly or gradually and may last briefly or become chronic. They’re a key sign of respiratory distress and neurologic deterioration. Causes include inadequate central respiratory control over breathing, neuromuscular disorders, increased resistance to airflow into the lungs, respiratory muscle fatigue or weakness, voluntary alterations in breathing, decreased activity from prolonged bed rest, and pain.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you observe shallow respirations, be alert for impending respiratory failure or arrest. Is the patient severely dyspneic? Agitated or frightened? Look for signs of airway obstruction. If the patient is choking, perform four back blows and then four abdominal thrusts to try to expel the foreign object. Use suction if secretions occlude the patient’s airway.

If the patient is also wheezing, check for stridor, nasal flaring, and accessory muscle use. Administer oxygen with a face mask or handheld resuscitation bag. Attempt to calm the patient. Administer epinephrine I.V.

If the patient loses consciousness, insert an artificial airway and prepare for endotracheal intubation and ventilatory support. Measure his tidal volume and minute volume with a Wright respirometer to determine the need for mechanical ventilation. (See Measuring Lung Volumes, page 632.) Check arterial blood gas (ABG) levels, heart rate, blood pressure, and oxygen saturation. Tachycardia, increased or decreased blood pressure, poor minute volume, and deteriorating ABG levels or oxygen saturation signal the need for intubation and mechanical ventilation.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in severe respiratory distress, begin with the history. Ask about chronic illness and surgery or trauma. Has he had a tetanus booster in the past 10 years? Does he have asthma, allergies, or a history of heart failure or vascular disease? Does he have a chronic respiratory disorder or respiratory tract infection, tuberculosis, or a neurologic or neuromuscular disease? Does he smoke? Obtain a drug history as well, and explore the possibility of drug abuse.

Measuring Lung Volumes

Use a Wright respirometer to measure tidal volume (the amount of air inspired with each breath) and minute volume (the volume of air inspired in a minute — or tidal volume multiplied by respiratory rate). You can connect the respirometer to an intubated patient’s airway via an endotracheal tube (shown here) or a tracheostomy tube. If the patient isn’t intubated, connect the respirometer to a face mask, making sure the seal over the patient’s mouth and nose is airtight.

Ask about the patient’s shallow respirations: When did they begin? How long do they last? What makes them subside? What aggravates them? Ask about changes in appetite, weight, activity level, and behavior.

Begin the physical examination by assessing the patient’s level of consciousness (LOC) and his orientation to time, person, and place. Observe spontaneous movements, and test muscle strength and deep tendon reflexes. Next, inspect the chest for deformities or abnormal movements such as intercostal retractions. Inspect the extremities for cyanosis and digital clubbing.

Now, palpate for expansion and diaphragmatic tactile fremitus, and percuss for hyperresonance or dullness. Auscultate for diminished, absent, or adventitious breath sounds and for abnormal or distant heart sounds. Do you note peripheral edema? Finally, examine the abdomen for distention, tenderness, or masses.

Medical Causes

- Acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS). Initially, ARDS produces rapid, shallow respirations and dyspnea. Hypoxemia leads to intercostal and suprasternal retractions, diaphoresis, and fluid accumulation, causing rhonchi and crackles. As hypoxemia worsens, the patient exhibits more difficulty breathing, restlessness, apprehension, a decreased LOC, cyanosis, and, possibly, tachycardia.

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). Respiratory muscle weakness in ALS causes progressive shallow respirations. Exertion may result in increased weakness and respiratory distress. ALS initially produces upper extremity muscle weakness and wasting, which in several years affect the trunk, neck, tongue, and muscles of the larynx, pharynx, and lower extremities. Associated signs and symptoms include muscle cramps and atrophy, hyperreflexia, slight spasticity of the legs, coarse fasciculations of the affected muscle, impaired speech, and difficulty chewing and swallowing.

- Asthma. With asthma, bronchospasm and hyperinflation of the lungs cause rapid, shallow respirations. In adults, mild persistent signs and symptoms may worsen during severe attacks. Related respiratory effects include wheezing, rhonchi, a dry cough, dyspnea, prolonged expirations, intercostal and supraclavicular retractions on inspiration, nasal flaring, and accessory muscle use. Chest tightness, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and flushing or cyanosis may occur.

- Atelectasis. Decreased lung expansion or pleuritic pain causes a sudden onset of rapid, shallow respirations. Other signs and symptoms include a dry cough, dyspnea, tachycardia, anxiety, cyanosis, and diaphoresis. Examination reveals dullness to percussion, decreased breath sounds and vocal fremitus, inspiratory lag, and substernal or intercostal retractions.

- Bronchiectasis. Increased secretions obstruct airflow in the lungs, leading to shallow respirations and a productive cough with copious, foul-smelling, mucopurulent sputum (a classic finding). Other findings include hemoptysis, wheezing, rhonchi, coarse crackles during inspiration, and late-stage clubbing. The patient may complain of weight loss, fatigue, exertional weakness and dyspnea on exertion, a fever, malaise, and halitosis.

- Coma. Rapid, shallow respirations result from neurologic dysfunction or restricted chest movement.

- Emphysema. Increased breathing effort causes muscle fatigue, leading to chronic shallow respirations. The patient may also display dyspnea, anorexia, malaise, tachypnea, diminished breath sounds, cyanosis, pursed-lip breathing, accessory muscle use, barrel chest, a chronic productive cough, and clubbing (a late sign).

- Flail chest. With flail chest, decreased air movement results in rapid, shallow respirations, paradoxical chest wall motion from rib instability, tachycardia, hypotension, ecchymoses, cyanosis, and pain over the affected area.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome. Progressive ascending paralysis causes a rapid or progressive onset of shallow respirations. Muscle weakness begins in the lower limbs and extends finally to the face. Associated findings include paresthesia, dysarthria, a diminished or an absent corneal reflex, nasal speech, dysphagia, ipsilateral loss of facial muscle control, and flaccid paralysis.

- Multiple sclerosis. Muscle weakness causes progressive shallow respirations. Early features include diplopia, blurred vision, and paresthesia. Other possible findings are nystagmus, constipation, paralysis, spasticity, hyperreflexia, intention tremor, an ataxic gait, dysphagia, dysarthria, urinary dysfunction, impotence, and emotional lability.

- Myasthenia gravis. Progression of myasthenia gravis causes respiratory muscle weakness marked by shallow respirations, dyspnea, and cyanosis. Other effects include fatigue, weak eye closure, ptosis, diplopia, and difficulty chewing and swallowing.

- Pleural effusion. With pleural effusion, restricted lung expansion causes shallow respirations, beginning suddenly or gradually. Other findings include a nonproductive cough, weight loss, dyspnea, and pleuritic chest pain. Examination reveals a pleural friction rub, tachycardia, tachypnea, decreased chest motion, flatness to percussion, egophony, decreased or absent breath sounds, and decreased tactile fremitus.

- Pneumothorax. Pneumothorax causes a sudden onset of shallow respirations and dyspnea. Related effects include tachycardia; tachypnea; sudden sharp, severe chest pain (commonly unilateral) that worsens with movement; a nonproductive cough; cyanosis; accessory muscle use; asymmetrical chest expansion; anxiety; restlessness; hyperresonance or tympany on the affected side; subcutaneous crepitation; decreased vocal fremitus; and diminished or absent breath sounds on the affected side.

- Pulmonary edema. Pulmonary vascular congestion causes rapid, shallow respirations. Early signs and symptoms include exertional dyspnea, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, a nonproductive cough, tachycardia, tachypnea, dependent crackles, and a ventricular gallop. Severe pulmonary edema produces more rapid, labored respirations; widespread crackles; a productive cough with frothy, bloody sputum; worsening tachycardia; arrhythmias; cold, clammy skin; cyanosis; hypotension; and a thready pulse.

- Pulmonary embolism. Pulmonary embolism causes sudden, rapid, shallow respirations and severe dyspnea with angina or pleuritic chest pain. Other clinical features include tachycardia, tachypnea, a nonproductive cough or a productive cough with blood-tinged sputum, a low-grade fever, restlessness, diaphoresis, a pleural friction rub, crackles, diffuse wheezing, dullness to percussion, decreased breath sounds, and signs of circulatory collapse. Less common findings are massive hemoptysis, chest splinting, leg edema, and (with a large embolism) cyanosis, syncope, and jugular vein distention.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Opioids, sedatives and hypnotics, tranquilizers, neuromuscular blockers, magnesium sulfate, and anesthetics can produce slow, shallow respirations.

- Surgery. After abdominal or thoracic surgery, pain associated with chest splinting and decreased chest wall motion may cause shallow respirations.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests: ABG analysis, pulmonary function tests, chest X-rays, or bronchoscopy.

Position the patient as nearly upright as possible to ease his breathing. (Help a postoperative patient splint his incision while coughing.) If he’s taking a drug that depresses respirations, follow all precautions, and monitor him closely. Ensure adequate hydration, and use humidification as needed to thin secretions and to relieve inflamed, dry, or irritated airway mucosa. Administer humidified oxygen, a bronchodilator, a mucolytic, an expectorant, or an antibiotic, as ordered. Perform tracheal suctioning, as needed, to clear secretions.

Turn the patient frequently. He may require chest physiotherapy, incentive spirometry, or intermittent positive pressure breathing. Monitor the patient for increasing lethargy, which may indicate rising carbon dioxide levels. Have emergency equipment at the patient’s bedside.

Patient Counseling

Explain the importance of coughing and deep breathing exercises. Provide emotional support and teach and encourage the caregiver to do so as well.

Pediatric Pointers

In children, shallow respirations commonly indicate a life-threatening condition. Airway obstruction can occur rapidly because of narrow passageways; if it does, administer back blows or chest thrusts but not abdominal thrusts, which can damage internal organs.

Causes of shallow respirations in infants and children include idiopathic (infant) respiratory distress syndrome, acute epiglottiditis, diphtheria, aspiration of a foreign body, croup, acute bronchiolitis, cystic fibrosis, and bacterial pneumonia.

Observe the child to detect apnea. As needed, use humidification and suction, and administer supplemental oxygen. Give parenteral fluids to ensure adequate hydration. Chest physiotherapy and postural drainage may be required.

Geriatric Pointers

Stiffness or deformity of the chest wall associated with aging may cause shallow respirations.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care. (7th ed). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Respirations, Stertorous

Characterized by a harsh, rattling, or snoring sound, stertorous respirations usually result from the vibration of relaxed oropharyngeal structures during sleep or coma, causing partial airway obstruction. Less commonly, these respirations result from retained mucus in the upper airway.

This common sign occurs in about 10% of healthy individuals; however, it’s especially prevalent in middle-age men who are obese. It may be aggravated by the use of alcohol or a sedative before bed, which increases oropharyngeal flaccidity, and by sleeping in the supine position, which allows the relaxed tongue to slip back into the airway. The major pathologic causes of stertorous respirations are obstructive sleep apnea and life-threatening upper airway obstruction associated with an oropharyngeal tumor or with uvular or palatal edema. This obstruction may also occur during the postictal phase of a generalized seizure when mucous secretions or a relaxed tongue blocks the airway.

Occasionally, stertorous respirations are mistaken for stridor, which is another sign of upper airway obstruction. However, stridor indicates laryngeal or tracheal obstruction, whereas stertorous respirations signal higher airway obstruction.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If you detect stertorous respirations, check the patient’s mouth and throat for edema, redness, masses, or foreign objects. If edema is marked, quickly take the patient’s vital signs, including oxygen saturation. Observe him for signs and symptoms of respiratory distress, such as dyspnea, tachypnea, accessory muscle use, intercostal muscle retractions, and cyanosis. Elevate the head of the bed 30 degrees to help ease breathing and reduce edema. Then, administer supplemental oxygen by nasal cannula or face mask, and prepare to intubate the patient, perform a tracheostomy, or provide mechanical ventilation. Insert an I.V. line for fluid and drug access, and begin cardiac monitoring.

If you detect stertorous respirations while the patient is sleeping, observe his breathing pattern for 3 to 4 minutes. Do noisy respirations cease when he turns on his side and recur when he assumes a supine position? Watch carefully for periods of apnea and note their length. When possible, question the patient’s partner about his snoring habits. Is she frequently awakened by the patient’s snoring? Does the snoring improve if the patient sleeps with the window open? Has she also observed the patient talk in his sleep or sleepwalk? Ask about signs of sleep deprivation, such as personality changes, headaches, daytime somnolence, or decreased mental acuity.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree