26 Public Health Practice in Communities

Chapters 24 and 25 discuss the organization and health of the public health system overall. This chapter discusses the theory and practice of improving community health. Theories are important because a theory-based program is more likely to be effective (see Chapter 15). The technical term for attempts to improve community health is community/program planning.

Community planning is defined as an organized process to design, implement, and evaluate a clinic or community-based project to address the needs of a defined population.1 Community planning is often the province of personnel in a public health agency, such as the commissioner of health or agency staff. However, the principles of community planning and evaluation pertain to any person who has a stake in improving the community (stakeholders, policy makers), including an employee of a foundation, school, mayor’s office, or political party and any interested citizen. Although there are many ideas on how to improve the health of a community, many good ideas fail. Reasons include lack of community or organizational support, lack of coordination, “turf battles,” inefficient and duplicative efforts, and failure to use evidence-based interventions. Careful planning before a project begins can make a significant impact on the success of the project.2

This chapter discusses the steps involved in planning and evaluating a program, highlighting two special applications of community planning: (1) tobacco prevention, as an example of multiple successful community interventions (Box 26-1), and (2) health disparities, one of the greatest public health problems. A community is only as strong as its weakest link. Therefore, public health practitioners should aim not just to raise health overall, but to raise most the health of the vulnerable populations. Box 26-2 lists some examples how health disparities have been successfully addressed.

Box 26-1 Prevention Efforts

Tobacco Use (Cigarette Smoking)

A. Credible evidence and effective interventions led to medical consensus:

1. Changes in understanding of the genesis of tobacco addiction reframed the problem as not one of individual control and choice, but of addiction. Evidence for harm to nonsmokers (secondary tobacco exposure) strengthened the case for regulation.

2. Behavioral and pharmacologic treatments became available, making it easier to support smokers desiring to quit.

B. Trusted experts and grassroots groups provided effective advocacy:

3. The American Cancer Society, American Lung Association, and American Heart Association were each advocating against tobacco independent from each other. In 1981 they formed a coalition on smoking, which was later joined by the American Medical Association. This broad coalition led legitimacy to the argument against smoking.

4. Grassroots efforts in many communities and from many sources changed cultural norms about smoking. Examples include flight attendants advocating for their right for a smoke-free workplace and the Reader’s Digest series educating its readers. These grassroots groups framed their issues as part of the broader environmental protection movement and increased consumer health consciousness.

C. Political will on many levels and available funds led to effective tobacco control.

5. On a federal level, Congress passed several laws addressing tobacco labeling, advertising on TV and radio, smoking bans on airlines and buses, and changes to FDA rules for more oversight over tobacco production and marketing.

6. States’ action. States used excise tax on tobacco to fund smoking control programs, which led to the development and evaluation of community-level approaches to tobacco control.

7. New litigation strategies opened up even more monies and created willingness in industry to agree to changes.

Reduce exposure to environmental tobacco smoke.

Reduce exposure to environmental tobacco smoke.

Reduce tobacco use initiation, especially among adolescents.

Reduce tobacco use initiation, especially among adolescents.

Recommended interventions include:

Smoking bans and restrictions in public areas, workplaces, and areas where people congregate

Smoking bans and restrictions in public areas, workplaces, and areas where people congregate

Increasing the unit price for tobacco products

Increasing the unit price for tobacco products

Mass media campaigns of extended duration using brief, recurring messages to motivate children and adolescents to remain tobacco free

Mass media campaigns of extended duration using brief, recurring messages to motivate children and adolescents to remain tobacco free

Provider reminders to counsel patients about tobacco cessation

Provider reminders to counsel patients about tobacco cessation

Provider education combined with such reminders

Provider education combined with such reminders

Reducing out-of-pocket expenses for effective cessation therapies

Reducing out-of-pocket expenses for effective cessation therapies

Multicomponent patient telephone support through a state quit line

Multicomponent patient telephone support through a state quit line

Modified from Institute of Medicine: Ending the tobacco problem: a blueprint for the nation, 2007; Task Force on Community Preventive Services (TFCPS): Recommendations regarding interventions to reduce tobacco use and exposure to environmental tobacco smoke, Am J Prev Med 20(2 suppl):10–15, 2001; and Tobacco. In Zaza S, Briss PA, Harris KW, editors: The guide to community preventive services: what works to promote health? Atlanta, 2005, Oxford University Press, http://www.thecommunityguide.org/tobacco/Tobacco.pdf.

Box 26-2 Addressing Health Disparities

Strong data skills with geographic mapping of premature death clusters and other determinants of health

Strong data skills with geographic mapping of premature death clusters and other determinants of health

Strong coalitions among agencies, community leaders, and other stakeholders

Strong coalitions among agencies, community leaders, and other stakeholders

Assessment of the community environment as a whole and addressing the social determinants at the root of health inequities (e.g., poverty, low rates for high school graduation, violence)

Assessment of the community environment as a whole and addressing the social determinants at the root of health inequities (e.g., poverty, low rates for high school graduation, violence)

Empowering communities to a sense of increased ownership and leadership

Empowering communities to a sense of increased ownership and leadership

Emphasizing community participation

Emphasizing community participation

Addressing environmental factors such as safe walkability, bikeability of environment, and access to high-quality food

Addressing environmental factors such as safe walkability, bikeability of environment, and access to high-quality food

Making health equity a component of all policies, including housing, youth violence, transportation, and agriculture

Making health equity a component of all policies, including housing, youth violence, transportation, and agriculture

Modified from Centers for Disease Control and Prevention: Health disparities and inequalities report (CHDIR), 2011. http://www.cdc.gov/minorityhealth/CHDIReport.html#ExecSummary. IOM reports on unequal treatment and reducing healthcare disparities. http://www.iom.edu/Reports/2011/State-and-Local-Policy-Initiatives-To-Reduce-Health-Disparities-Workshop-Summary.aspx

Many models and acronyms describe the steps of community planning (Box 26-3). They all have their strengths and weaknesses. We follow mainly the steps outlined in the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) model, Community Health Assessment and Group Evaluation (CHANGE).3 Other models are described in the section that addresses their main emphasis. Any other model of community planning likely works equally well as long as planners follow the following basic principles:

Assemble community stakeholders and, in collaboration with them, define the agenda, values, and priorities.

Assemble community stakeholders and, in collaboration with them, define the agenda, values, and priorities.

Design measurable objectives and interventions.

Design measurable objectives and interventions.

Choose multilevel approaches rather than single interventions.

Choose multilevel approaches rather than single interventions.

Box 26-3 Frequently Used Acronyms in Program Planning

| CBPR | Community-Based Participatory Research |

| CHANGE | Community Health Assessment and Group Evaluation |

| DEBI | Diffusion of Effective Behavioral Interventions |

| DOI | Diffusion of Innovations |

| HEDIS | Healthcare Effectiveness Data and Information Set |

| IOM | Institute of Medicine |

| MAP-IT | Mobilize, Assess, Plan, Implement, Track |

| MAPP | Mobilizing for Action through Planning and Partnerships |

| NACCHO | National Association of County and City Health Officials |

| NCQA | National Committee for Quality Assurance |

| NPHPSP | National Public Health Performance Standards Program |

| P.L.A.N.E.T. | Plan, Link, Act, Network with Evidence-based Tools |

| PAR | Participatory Action Research |

| PATCH | Planned Approach to Community Health |

| PRECEDE | Predisposing, Reinforcing, and Enabling Constructs in Educational Diagnosis and Evaluation |

| PROCEED | Policy, Regulatory, and Organizational Constructs in Educational and Environmental Development |

| RTIP | Research Tested Intervention Program |

| RE-AIM | Reach, Efficacy,Adoption, Implementation, Maintenance |

| SCT | Social Cognitive Theory |

| SMART | Specific, Measurable, Attainable, Relevant, and Timely |

| SPARC | Sickness Prevention Achieved through Regional Collaboration |

| VERB | Not an acronym, but a program emphasizing verb as a part of speech, meaning an action word |

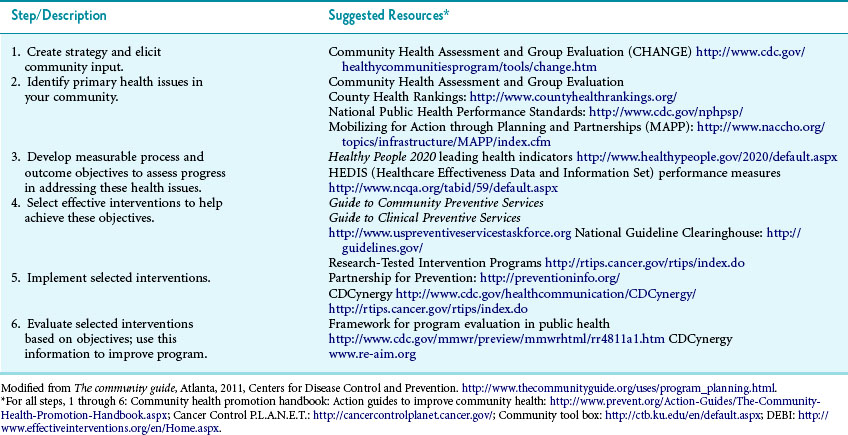

Table 26-1 provides an overview of the process and possible resources for each step.

I Theories of Community Change

When behavioral factors are a threat to health, improving health requires behavior change. Unhealthy behaviors (e.g., sedentariness) need to be replaced by healthy ones (e.g., exercise). Individual behavior, however, does not occur in a vacuum; it is strongly influenced by group norms and environmental cues. Practitioners aiming to change group norms and environmental cues should be aware of theories of community changes. This is because, as with any behavior change, practitioners will have a higher chance of success if they intervene in accordance with a valid theory of behavior change (see Chapter 15 for theories of individual behavior change.) A number of theories have been developed to describe how individual change is brought about through interpersonal interactions and community interventions. These theories can be broadly characterized as cognitive-behavioral theories and share the following key concepts:

Knowledge is necessary, but is not in itself sufficient to produce behavior changes.

Knowledge is necessary, but is not in itself sufficient to produce behavior changes.

Perceptions, motivations, skills, and social environment are key influences on behavior.

Perceptions, motivations, skills, and social environment are key influences on behavior.

Interpersonal: Family, friends, and peers provide role models, social identity, and support.

Organizations: Organizations influence behavior through organizational change, diffusion of innovation, and social marketing strategies.

Community: Social marketing and community organizing can change community norms on behavior.

Public policy: Public opinion process and policy changes can change the incentives for certain behaviors and make them easier or more difficult (e.g., taxes on high-sugar beverages).

A Social Cognitive Theory

Social cognitive theory (SCT) is one of the most frequently used and robust health behavior theories.4 It explores the reciprocal interactions of people and their environments and the psychosocial determinants of health behavior (see Chapter 15).

Environment, people, and their behavior constantly influence each other (reciprocal determinism). Behavior is not simply the result of the environment and the person, just as the environment is not simply the result of the person and behavior.5 According to SCT, three main factors affect the likelihood that a person will change a health behavior: (1) self-efficacy (see Chapter 15), (2) goals, and (3) outcome expectancies, in which people form new norms or new expectations from observing others (observational learning).

B Community Organization

Social capital refers to social resources such as trust, reciprocity, and civic engagement that exist as a result of network between community members. Social capital can connect individuals in a fragmented community across social boundaries and power hierarchies and can facilitate community building and organization. Social networking techniques and increasing the social support are vital methods that build social capital.6

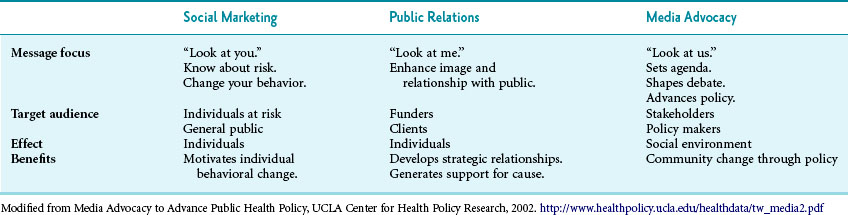

Media advocacy is an essential component of community organizing. It aims to change the way community members look at various problems and to motivate community members and policy makers to become involved. This occurs through a reliable, consistent stream of publicity about an organization’s mission and activities, including articles and news items about public health issues. Media advocacy relies on mass media, which make it expensive. In the 21st century, social media and games can generate extensive publicity with minimal investment. Table 26-2 summarizes how social marketing, public relations, and media advocacy complement each other.

1 Participatory Research

Immigrants and racial or ethnic minorities often distrust the health care system, making it more difficult for researchers and health practitioners to identify and address the health needs of these communities. For these groups, as well as for building community capacity in general, various participatory research methods have been proposed. Participatory efforts combine community capacity–building strategies with research to bridge the gap between the knowledge produced and its translation into interventions and policies.7

Participatory action research (PAR) and community-based participatory research (CBPR) are two participatory research approaches that have gained increasing popularity since the late 1980s.8 Both PAR and CBPR conceptualize community members and researchers working together to generate hypotheses, conduct research, take action, and learn together. PAR focuses on the researcher’s direct actions within a participatory community and aims to improve the performance quality of the community or an area of concern.9–12 In contrast, CBPR strives for an action-oriented approach to research as an equal partnership between traditionally trained experts and members of a community. The community members are partners in the research, not subjects.13 Both approaches give voice to disadvantaged communities and increase their control and ownership of community improvement activities.10,13,14

The guidelines for participatory research in health promotion15 describe seven stages in participation, from passive or no participation to self-mobilization. For both approaches, the process is more important than the output, goals and methods are determined collaboratively, and findings and knowledge are disseminated to all partners.10,13 Participatory research is more difficult to execute because of greater time demands and challenges in complying with external funding requirements.16–18 For example, if actions require a negotiated process with the community, they may divert from a project plan previously submitted to a funder.

Engaging the community in research efforts is essential in translating research into practice. However, there are still large gaps in translating conclusions from well-conducted randomized trials into community practice. The Multisite Translational Community Trial is a research tool designed to bridge the gap. This trial type explores what is needed to make results from trials workable and effective in real-world settings and is particularly suited to practice-based research networks such as the Prevention Research Centers.19

C Diffusion of Innovations Theory

To be successful, a community strategy needs to be disseminated. Successful dissemination is called diffusion. Diffusion of innovations (DOI) theory is characterized by four elements: innovations, communication channels, social systems (the individuals who adopt the innovation), and diffusion time. The DOI literature is replete with examples of successful diffusion of health behaviors and programs, including condom use, smoking cessation, and use of new tests and technologies by health practitioners.20 Although DOI theory can be applied to behaviors, it is most closely associated with devices or products.

Groups are segmented by the speed with which they will adopt innovations. Innovators are eager to embrace new concepts. Next, early adopters will try out innovations, followed by members of the early majority and late majority. Laggards are the last to accept an innovation. Consequently, innovations need to be marketed initially to innovators and early adopters, then need to address each segment in sequence. The relevant population segments are generally referred to as innovators 2.5% of the overall population), early adopters (13.5%), early majority (34%), late majority (34%), and laggards (16%).20

Compatibility, the degree to which an innovation is perceived to be consistent with the existing values, current processes, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters

Compatibility, the degree to which an innovation is perceived to be consistent with the existing values, current processes, past experiences, and needs of potential adopters

Low complexity, the degree to which an innovation is perceived as easy to use

Low complexity, the degree to which an innovation is perceived as easy to use

Trialability, the opportunity to experiment with the innovation on a limited basis

Trialability, the opportunity to experiment with the innovation on a limited basis

Observability, the degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others

Observability, the degree to which the results of an innovation are visible to others

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree