Proximal Gastrectomy

Sushanth Reddy

Martin J. Heslin

DEFINITION

Proximal gastrectomy is defined as a procedure to remove the upper third to one-half of the stomach and the distal portion of the esophagus. This is a procedure to remove cancers or premalignant lesions in the cardia of the stomach, the gastroesophageal (GE) junction, or the distal esophagus. Proximal gastrectomy is usually used in conjunction with systemic chemotherapy and external beam radiation for malignant lesions in this area.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

Patients typically present with difficulty swallowing, dysphagia, upper gastrointestinal (GI) bleeding, or reflux symptoms, especially in the setting of unexplained weight loss. Initial diagnostic evaluation typically includes an esophagogastroduodenoscopy (EGD) with biopsy showing malignancy.

A thorough history and physical examination should be performed prior to surgery. Particular attention should be paid to cardiac and pulmonary comorbidities and nutritional status. Risk factors for cancer including acid reflux disease, history of Barrett’s esophagus, and tobacco use should be identified.

Patients who have disease in the proximal to midesophagus should not undergo proximal gastrectomy.1 These patients should be considered for either an Ivor-Lewis (Part 1, Chapter 30) or transhiatal esophagectomy (Part 1, Chapter 29).

All patients with cancer should undergo staging prior to consideration for surgery.

Patients with high-grade dysplasia or T1 tumors without lymph node metastases should be considered for surgery first. Patients with advanced tumors (T2 or greater) or those with lymph node involvement should be considered for upfront (neoadjuvant) chemotherapy and radiation therapy.2,3 Those patients who are nutritionally depleted should have a feeding jejunostomy tube placed prior to initiating therapy.4

Following completion of chemotherapy and radiation therapy, patients should be restaged. The presence of distant metastases is a contraindication for surgery.

The period of upfront therapy allows for optimization of cardiac and pulmonary comorbidities prior to surgery.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

All patients should undergo staging evaluation prior to surgery. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) is used to identify tumor depth (T stage) and regional lymph node metastases (N stage). Computed tomography (CT) scan or positron emission tomography (PET) scan is used to identify distant metastases. The liver is the most common site of distant metastases for adenocarcinoma and squamous cell carcinoma (the two most common tumor histologies).

Staging should be repeated after the completion of upfront chemotherapy prior to surgery.

The celiac axis anatomy should be carefully studied prior to surgery to look for anomalies. Specific attention should be paid toward an accessory or replaced left hepatic artery within the gastrohepatic ligament.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Many patients with gastric or esophageal malignancy have comorbid conditions related to age or tobacco use. These patients should undergo optimization of their comorbidities prior to surgery.

Anesthesia should consider placement of an arterial monitoring catheter and/or a central venous catheter. During hiatal dissection, the heart may be compressed and invasive monitoring can be useful in guiding resuscitation in the operating room.

A nasogastric (NG) tube will be placed during the operation. It may not be possible to pass an NG tube prior to removal of the tumor (if it is obstructing). The surgeon should have good communication with anesthesia in regard to NG tube position as it will be manipulated through the operation.

Positioning

The patient is positioned with both arms at 90 degrees with the torso. This will facilitate with exposure by spreading the lower ribs laterally. Alternatively the right arm can be tucked to the patient’s side to aid in attachment of the self-retaining retractor device to the operating room table. If a feeding jejunostomy tube has already been placed, the tube should be prepped into the sterile field.

TECHNIQUES

DIAGNOSTIC LAPAROSCOPY

The abdomen is entered through the supraumbilical midline and a laparoscope placed (Part 2, Chapter 13). The entire abdomen should be evaluated with specific attention to the liver and the peritoneal surfaces for the presence of metastatic disease. Any suspicious lesions should be biopsied and sent for frozen section analysis in the pathology. The presence of metastatic disease is a contraindication for surgical resection.

MOBILIZATION OF THE STOMACH

A formal laparotomy is performed and a self-retaining retractor is placed. Excision of the xiphoid process may be used to aid with retraction (this allows for wider retraction of the costal margin).

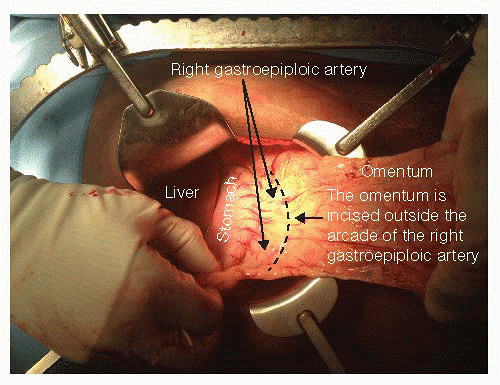

The lesser sac is entered along the avascular plane that separates the gastrocolic omentum from the transverse mesocolon. The dissection should proceed away from the greater curve of the stomach to avoid injury to the right gastroepiploic artery. The right gastroepiploic artery will be the primary blood supply of the residual stomach (FIG 1). The right gastric artery can be spared to keep the gastric conduit well vascularized. Mobilization of the stomach is usually sufficient for resection and reconstruction for a proximal gastrectomy without the need for ligation of the right gastric artery and a Kocher maneuver to mobilize the duodenum (needed for transhiatal esophagectomy [Part 1, Chapter 29] or Ivor-Lewis esophagectomy [Part 1, Chapter 30]).

The left lateral section of the liver is mobilized to expose the lesser curve of the stomach and the esophageal hiatus: The left triangular ligament is incised. This is avascular. The falciform ligament may also be incised to aid with visualization of the left triangular ligament (FIG 2). The ligament need not be mobilized to its confluence with the falciform to avoid injury to the left hepatic vein. The gastrohepatic ligament is divided. This structure is typically also avascular, but attention should be paid for any accessory or replaced left hepatic artery (FIG 3). This will allow exposure of the esophageal crura.

The gastrosplenic ligament is divided between clamps and ties. The vasa brevia are individually dissected and divided between ties. Alternative strategies for division of this structure would include an advanced energy device or an articulating 45-mm stapler with vascular loads.

FIG 1 • The greater curve of the stomach is mobilized. Care is taken to stay outside the right gastroepiploic artery as this is the vascular pedicle of the gastric conduit. This portion of the gastrocolic omentum is typically avascular, although small blood vessels may be encountered requiring ligation. The vasa brevia should be ligated as dissection proceeds cephalad.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access

Get Clinical Tree app for offline access