Patient Story

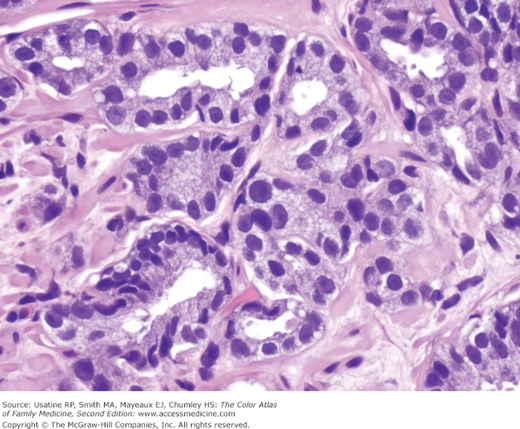

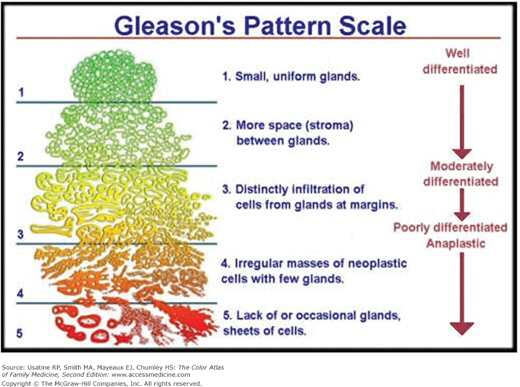

A 65-year-old man in good health comes to the office having had a prostate specific antigen (PSA) test performed at a local health fair. He reports a normal voiding pattern and normal erectile function with no evidence of weight loss or bone pain. He has no major medical problems but does have a strong family history of prostate cancer. His PSA is 9.3 ng/mL and he chooses to have a prostate biopsy. Pathology demonstrates prostate cancer with a Gleason score of 6 (Figure 73-1).

Introduction

Prostate cancer is a very common cancer in men. Secondary to widespread testing, we have seen a stage migration in prostate cancer. Most patients are diagnosed with asymptomatic, clinically localized disease. Multiple factors such as Gleason score, PSA level, stage at diagnosis, and life expectancy are all factors applied to risk stratify patients associated with varying possibilities of achieving a cure. It is especially important to consider life expectancy prior to offering PSA screening.

Epidemiology

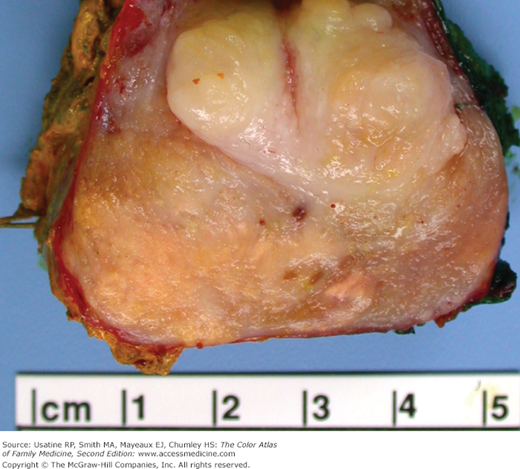

- Prostate cancer (Figure 73-2) is the leading cancer in U.S. men and the second leading cause of cancer deaths in men.1

- It is the second most common cancer in men worldwide, with an estimated 900,000 cases and 258,000 deaths in 2008.2

- Incidence is increased with age.

- The risk of developing prostate cancer increases at age 40 years in black men and in those who have a first-degree relative with prostate cancer.

- The risk of developing prostate cancer begins to increase at age 50 years in white men who have no family history of the disease.3

- There is no peak age or modal distribution.

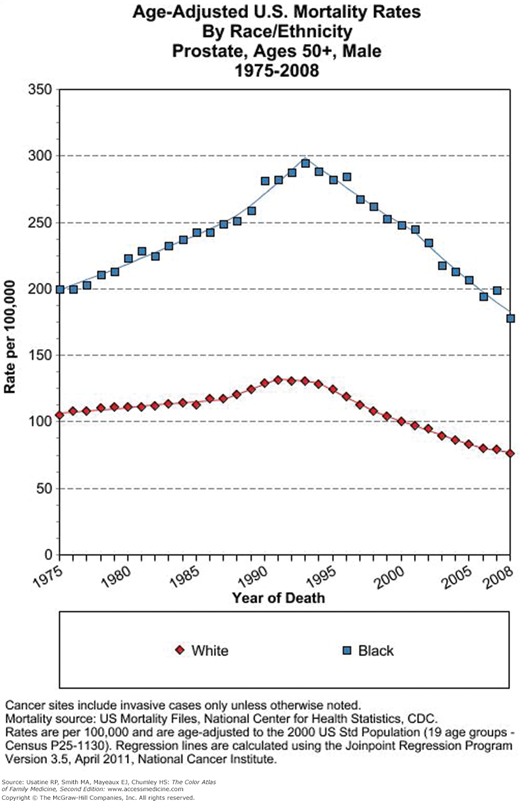

- The highest incidence of prostate cancer in the world is found in African American men, who have approximately a 9.8% lifetime risk of developing prostate cancer. There is accompanied by a high rate of prostate cancer mortality (Figure 73-3).

- The lifetime risk of prostate cancer for white men in the United States is 8%.3

- Japanese and mainland Chinese populations have the lowest rates of prostate cancer.

- Socioeconomic status appears to be unrelated to the risk of prostate cancer.

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Greater than 95% of prostate cancers are adenocarcinomas.

- Histologic variants include ductal or endometrioid carcinoma, mucinous adenocarcinoma, signet cell carcinoma, small cell carcinoma, squamous and adenosquamous carcinoma, basaloid and adenoid cystic carcinoma.

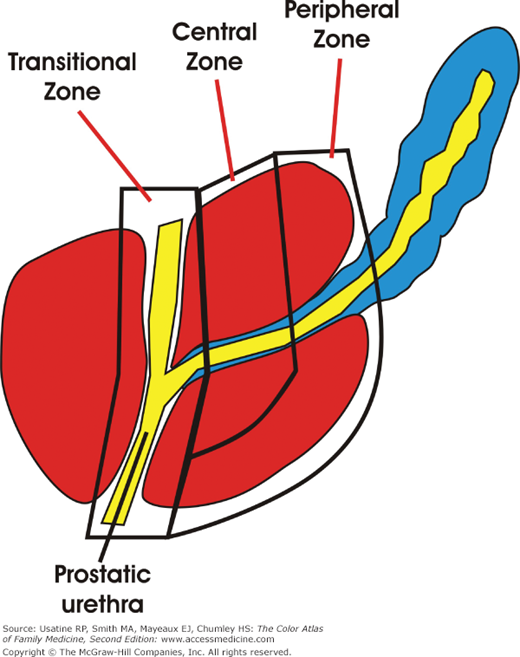

- Of prostate adenocarcinomas, 70% occur in the peripheral zone, 20% in the transitional zone, and approximately 10% in the central zone (Figure 73-4).

- Biologic behavior is affected by histologic grade as described by the Gleason Grade and Score (Figure 73-5). The Gleason grade is based on the architectural pattern of prostate cancer cells. Based upon the growth pattern and differentiation, tumors are graded from 1 to 5, with grade 1 being the most differentiated and grade 5 the least differentiated. One grade is assigned to the most common tumor pattern, and a second grade to the next most common tumor pattern. The Gleason Score is obtained by adding the two grades together and ranges from 2 to 10. A higher score indicates a greater likelihood of having non-organ-confined disease, as well as a worse outcome after treatment of localized disease.

- Patterns of spread include direct extension, hematogenous, and lymphatic.

- Lymphatic spread occurs to the hypogastric, obturator, external iliac, presacral, common iliac, and paraaortic nodes.4

- Of distant metastases, 90% are osseous.

- Visceral metastases to lung, liver, and adrenals are less commonly seen without bone involvement.4

- Of distant metastases, 90% are osseous.

Risk Factors

Diagnosis

- Prostate cancer can be associated with urinary obstructive symptoms or hematuria, but these are usually a result of other causes.

- Rarely, bone pain can be an initial symptom, but it generally represents very advanced disease. Prior to PSA screening, men commonly presented with this symptom.

- A prostatic nodule on digital rectal examination (DRE) is not always specific for a carcinoma and can underestimate the extent of disease when it does represent a carcinoma.

- PSA is a glycoprotein produced primarily by the epithelial cells that line the acini and ducts of the prostate gland.

- PSA is concentrated in prostatic tissue, and serum PSA levels are normally very low.

- Disruption of the normal prostatic architecture, such as by prostatic disease, inflammation, or trauma, allows greater amounts of PSA to enter the general circulation.5

- The sensitivity and specificity for PSA as a detection tool is 80% and 65%, respectively.5 After treatment PSA is the primary tool used to evaluate for persistent disease or metastatic disease before imaging is employed.

- The American Urological Association guidelines support screening from age 40 years old to 75 years old.6

- The U.S. Prevention Task Force (USPSTF) has published final recommendations against PSA-based screening for prostate cancer in asymptomatic men.7

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree