Project Management: Balancing Line Function and Matrix Approaches

Because change is so rapid it is not uncommon for an individual in midcareer to find that the hierarchy is passing him by. In other words, he has climbed part way up the ladder and feels competent. He stops to rest, but rapid technological change goes on. He intends to catch up, but when he tries he is technologically obsolete. He has become uneducated for his job simply by standing still.

–Laurence J. Peter. From The Peter Prescription.

There’s no “I” in team.

–Anonymous

DEFINITIONS AND BACKGROUND

General Description of a Matrix

The management hierarchy present in almost all companies is referred to as line management. This is the so-called pyramid or vertical system where people report to others above them in a chain of command. There is a second management system referred to as the matrix or horizontal system that is used for drug development by most medium and large pharmaceutical companies, as well as by some smaller pharmaceutical companies. In this system, each new drug or line extension of a drug that is being developed is called a project. The progress of each project is planned, facilitated, and reviewed by an interdisciplinary group of members referred to as the project team. People who perform the work on a drug or who are responsible for the work may be a project team member or may informally (or formally) report to the team

member from their department or discipline. The disciplines represented on most projects include:

member from their department or discipline. The disciplines represented on most projects include:

Pharmacology

Toxicology

Technical development areas [e.g., chemical development, analytical development, pharmaceutical (formulation) development]

Statistics

Regulatory affairs

Project planning

Clinical

At some pharmaceutical companies, the project team also includes marketing- and business-oriented members. Each team has a leader or manager who reports (possibly on an informal basis) to an individual who serves as head of the matrix who then reports either through line management or directly to the head of research and development.

The matrix system represents a second reporting relationship in addition to line management. At some companies, the matrix reporting relationship is formal, and this may lead to conflicts with line managers. A major technique used to avoid these conflicts is to have matrix-reporting relationships be loose and informal. Interpersonal skills, diplomacy, tact, and, above all, a desire for this system to work are required to have a successful system.

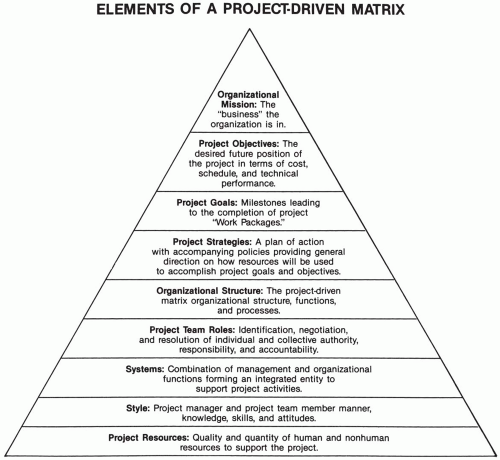

The major aspects of developing drugs using a project-driven matrix management approach may be broken down into various components. Cleland (1984) has proposed nine elements in this philosophy, which are shown in Fig. 48.1.

Levels within an Organization at Which Matrix Groups May Function

The matrix function usually is most visible in a company when it is used to develop new drugs toward an Investigational New Drug Application (IND) and a New Drug Application (NDA). A matrix approach to management also functions at several other levels within a company. At the most general level, the matrix concept

may be used to organize an entire company. Chapter 19 describes various organizational aspects of this approach. Figure 19.3 illustrates how this concept can be used to organize a company, and Fig. 41.3 illustrates the use of a matrix approach for organizing a research and development group.

may be used to organize an entire company. Chapter 19 describes various organizational aspects of this approach. Figure 19.3 illustrates how this concept can be used to organize a company, and Fig. 41.3 illustrates the use of a matrix approach for organizing a research and development group.

Internationally

At the international level, members from various countries, who are part of a multinational company, work on teams (or committees). Such teams exist and operate at different levels of the company’s hierarchy. This topic is discussed further in Chapter 47. These teams may be concerned with international policies, strategies, plans, and/or activities. These groups or teams may focus on one or more of the following functions: establishing, monitoring, reviewing, problem solving, or coordinating. In many ways, the board of directors, which is composed of both staff members and senior line managers from different countries, is a matrix function. It is the team that operates at the company’s highest level.

Nationally

Many types of matrix groups function at the national level. There are numerous areas where people from different disciplines get together outside the traditional hierarchical structure of the company. Most of these groups have other names, such as task forces, and many are used on a temporary basis. All issues and functions described under the international level may also operate at the national company level.

Drug Development

This level relates to the project groups (i.e., teams) that are planning and carrying out the many activities of drug development. Project teams may be national and/or international in their make-up. Figure 41.3 illustrates how project teams report in a matrix organization. This is the activity that is usually referred to when one reads about project groups or teams in the pharmaceutical industry.

Research Projects

The matrix approach within research and development may be used to assist drug discovery as well as drug development activities. For drug discovery, an independent team of scientists from different disciplines and/or departments (e.g., chemistry, biochemistry, pharmacology, and microbiology) may work together on a formal or informal basis. This group may focus its efforts and goals on one or more therapeutic areas (e.g., cardiology and gastroenterology), diseases (e.g., angina and sickle cell disease), physiological effects (e.g., to shift the oxygen dissociation curve to the right), biochemical effects (e.g., to stimulate or inhibit a specific enzyme), or pathological effects (e.g., to prevent necrosis from developing in ischemic tissues). This group may have a member who helps the team by (a) coordinating its activities, (b) monitoring its progress, (c) communicating its activities and results to senior management, (d) drawing up plans for advanced testing of active compounds, and (e) helping to facilitate the resolution of disputes or other issues. Various organizational structures used for drug discovery are shown in Fig. 41.5. The matrix approach tends to be more informal at the early stages of drug discovery and more structured at later phases of preclinical research when a specific compound is being evaluated and considered for further development.

KEY PLAYERS IN A MATRIX SYSTEM

Overseeing a Matrix System

At both national and international levels, it is generally valuable to have a small department oversee the matrix system. The functions of this department would include planning, monitoring, troubleshooting, and facilitating solutions to problems. Other major activities could include generating financial records (e.g., tracking project costs), conducting analyses of the project system, and serving as a source to collect and analyze archival information.

At each level where one or more matrix groups may function, there may be an individual who is assigned the role of coordinating activities. This person may or may not be a member of the individual project teams. If no one is assigned this coordinating responsibility, it becomes the function of the groups’ leaders and/or line managers. In addition to the person who coordinates activities, any department with a representative on the team may also have a separate individual (or group) that coordinates all activities and all clinical trials conducted within their department.

Most pharmaceutical companies benefit if they have an individual who has few line managerial responsibilities in charge of coordinating and improving the efficiency of international drug development and project-related activities. This person receives information about activities and problems from all drug development groups. He or she provides input where needed to keep communications lines operational and ensures that all relevant groups are communicating effectively.

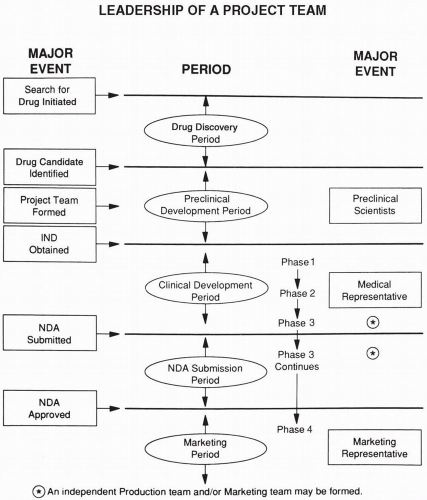

Project Team Leaders

The leader of a project team is usually appointed by one or more senior managers through either a formal or informal mechanism. A project team may have a single leader for its entire life, but often there are two or more leaders, although at different points in the project’s life. One common pattern is to have a preclinical scientist lead a project until an IND is filed and clinical trials are initiated. The project is then turned over to a clinician who leads the project until the NDA is approved. After that point, a marketing-oriented individual is appointed to lead the project. A separate project team of primarily different members who focus on production and marketing issues may be created at any time, but this is likely to occur during Phase 3 (Fig. 48.2). The advantage of forming a separate team in production and/or marketing is that it enables each group to function more efficiently because each is primarily concerned with different activities. A few people, especially the project team leaders, should be on both (or all) teams. This helps ensure close coordination of efforts. The same principles apply to a research and development team established in two separate countries where the drug is being developed (see Chapter 47).

Project Champions

Project leaders are often viewed as project champions. To obtain project leaders who are effective project champions, it is important that project leadership be viewed as a privilege and honor rather than as a burden or as a reward for other services or work. If people are merely rewarded for their hard work in their own discipline by being made a project leader, it is more likely that they will not do as effective a job as those people chosen

because they are the best candidates. Individuals who are most highly motivated to act as project champions are often chosen as project leaders.

because they are the best candidates. Individuals who are most highly motivated to act as project champions are often chosen as project leaders.

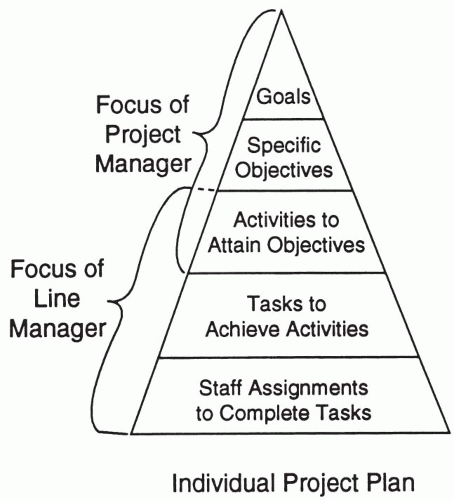

Project Team Managers

A totally different approach to providing project leadership is practiced by those companies that have project managers. These individuals are not primarily scientists or clinicians but, instead, are full-time managers of a small number of projects. Managers are chosen for their administrative ability to move projects ahead rapidly, efficiently, and in the desired direction. Good project managers are independent, aggressive, and objective; pay attention to detail; and have a high level of interpersonal skills. They usually have a scientific or medical background because some scientific training is usually important for their success with new chemical entity projects. People with a PhD or MD are desirable candidates if they also possess the other characteristics described. Individuals with a business, production, or marketing background could also be suitable candidates for selected types of projects (e.g., over-the-counter drugs, marketed prescription drugs, and Phase 3

drugs), especially if they have demonstrated the requisite skills and talents. The differences in focus between project managers and line managers on a project are shown in Fig. 48.3.

drugs), especially if they have demonstrated the requisite skills and talents. The differences in focus between project managers and line managers on a project are shown in Fig. 48.3.

Utilizing Project Managers versus Project Leaders

Major advantages of having project managers rather than project leaders are that the managers do not have commitments to line-function managers and do not have the responsibility of also running a program in their own discipline (e.g., the drug’s entire clinical program). Therefore, they have more time to devote to helping the project stay on schedule and to deal with administrative issues than do project leaders. Project managers also tend to be more objective and independent about decisions they make. Managers are also desirable to use when a company has too few project champions or when it is difficult for champions to cross department boundaries to have work accomplished.

It is the author’s opinion that most companies will utilize project managers rather than project champions/project leaders in the future. The project managers are professionals whose job is to achieve the project’s goals and milestones, and their performance is judged by the success of this effort. The project leader is often an “amateur” at leading a project, and his or her line managers (i.e., supervisors) may even resent the time spent on directing a project, especially if it interferes with the “higher priorities” of this professional. It is inefficient for a company continually to identify and then to train new champions for a long period before they become effective project leaders. Moreover, project leaders almost always focus their energies on achieving their discipline or function goals. Many professionals who would be the best project leaders have insufficient time to devote to running a project because of their almost total commitment to their line-function responsibilities.

Alternative Approaches

Two alternative systems to using a pure project leader or project manager system are as follows:

A transition system. One example of a transition system is for project leaders to head projects from their inception through the Phase 2 go-no go decision point. Once this decision is reached, the project is turned over to a project manager who leads the project administratively until the drug is marketed. The past project leader usually continues to remain active on the project within his or her discipline (e.g., clinical research). This system has the disadvantage that the transition occurs at one of the busiest times in the project’s life.

A combination system. An example of a combination system is to have project leaders focus on scientific and policy issues (e.g., strategies and objectives) and an assistant project leader focus on administrative issues (e.g., planning, tracking, writing reports, and troubleshooting). Each person who has this administrative role could assist from one to six or so project leaders, depending on the work load within each project.

Project Team Members

It should be clear to the project leader (or manager) why each member of their team was appointed. The reasons could include (a) providing invaluable expertise, (b) providing an opportunity to learn about a new activity or therapeutic area, or (c) being drafted because no one else was interested, available, or willing to serve. Some teams change their membership rather frequently as the project goes through various stages along the drug development pipeline. If there is any confusion about who is actually on the team, this issue should be rapidly settled by the project leader. This is usually resolved through discussions with project members, department heads, or senior managers. Some companies appoint department heads to serve as members of a project team, but most companies appoint more junior personnel.

Project Coordinators/Planners

An important member of the project team is the person who serves as navigator for the project. Whereas the project leader serves as the captain, each project needs an individual to draw up plans, track progress, and help ensure that the project remains on course. This individual raises a red flag when the project goes astray or runs into problems. This individual usually reports to a separate department of project coordination or project management and has limited authority to facilitate a solution to problems or issues, although they are often the ones who identify issues or problems that are likely to arise or have arisen.

The role of project coordinator is not clearly defined at most companies, which has both advantages and disadvantages. The advantages include the ability to be more effective in expediting those services most needed by the project (e.g., tracking the writing and reviewing of various reports, tracking drug use and need, and following competitors’ activities). The disadvantages include the ability of the project leader (a) to exclude this individual from information needed to perform his or her role effectively,

(b) to ignore this individual’s role and work, and (c) to have another individual in the project leader’s own discipline carry out much of this work. Solutions for the coordinator often relate to finding those services that the project leader desires and can use in running the project. If a project manager is running the project, then a project coordinator may act as an assistant project manager. Another approach to finding a solution is to strengthen the matrix system so that the responsibilities of the coordinator are more clearly defined and accepted by the project team.

(b) to ignore this individual’s role and work, and (c) to have another individual in the project leader’s own discipline carry out much of this work. Solutions for the coordinator often relate to finding those services that the project leader desires and can use in running the project. If a project manager is running the project, then a project coordinator may act as an assistant project manager. Another approach to finding a solution is to strengthen the matrix system so that the responsibilities of the coordinator are more clearly defined and accepted by the project team.

INITIATING NEW PROJECTS

Initiating Projects in a Multinational Pharmaceutical Company

One of the most basic issues in a project system is whether or not a compound must meet formal criteria prior to elevation to project status. These criteria could be established in terms of scientific profile, medical need, and commercial value. If a multinational company develops drugs at two or more separate sites, it is possible that new projects may be only established or initiated by the central headquarters, or initiation may occur at each of the semi-independent sites developing drugs. If the latter situation prevails, then it must be determined how each site is to react to projects initiated by the other sites. Their reactions could be to do nothing except to follow the new project’s progress, form an independent group that would also develop the drug, or develop an international project team. Another approach to establishing new projects is to require joint approval of new projects by all sites where the drug will be developed.

Types of Projects Initiated

Some companies believe in one type of drug project (i.e., all investigational drugs are intended to be marketed unless work is terminated by toxicity, by lack of efficacy, or for another reason). Other companies or even a different site within the same company may believe that some projects should be established to test a theory, even though it is known that the compound being tested will not become a marketed drug. The author believes that this second type of project should only rarely be initiated by pharmaceutical companies. Whichever approach a company decides on, the nature of the project for each compound and drug must be clear and transparent.

Number of Projects Initiated

How should a company react if a very large number of compounds simultaneously come through internal discovery activity and are proposed for development and eventual marketing? The first principle is that everything possible should be done to make the staff proposing the new compounds for project status feel that their accomplishments are greatly appreciated and will lead to success for the company. At the same time, it is important to stress that the company’s resources are stretched and cannot presently pay adequate attention to each. The scientists should be encouraged to learn more about their compound in toxicology, metabolism, and other areas of preclinical science before it is made a project. While this may cause a delay in the progress of the project, it increases the amount of data collected before a compound is made into a project.

Another generally less desirable approach is to fill the project system to overflowing in the expectation that a number of projects will drop out and allow the best projects to continue. While this assumption is valid, the danger is that this approach to creating a project portfolio will slow development of the higher priority projects that are competing for resources at the early stages of development. This should be able to be addressed by assigning different priorities to the various projects that are entering the system. Even if a new project is assigned a low priority, this usually sanctions the project for a longer life than if higher standards are used before the compound can enter the project system.

Licensing the compound to another company is rarely a worthwhile strategy at an early stage of development. Even if the company has other similar drugs in development, it is uncertain which one will ultimately be the best and the most successful. In addition, up-front payments and royalties received are relatively small compared to the financial return if the company developed the drug itself.

Getting a Project Off the Ground and Moving Ahead

Some of the many issues that must be dealt with in starting a new project and maintaining the momentum of existing ones include:

Authority. Where is it, and how will it be used? How much is the direct authority of those involved, and how much is indirectly derived by personal or reporting connections to those who have direct authority? Also, are there managers who exert authority, although there is no evidence that they have a right to do so (i.e., that authority was delegated to them from more senior managers)? If a project team is composed of department heads or more senior managers, then this will not be an issue, whereas if junior people are members, then it may represent a major problem.

Communication. What are the processes and mechanisms to be used in communicating both to higher and lower levels in the company? Are they operating efficiently? How could they be improved?

Decision making. Who makes decisions at each level in the company, and how are they made? Are issues raised for debate as a “front” after the real decision has been made? For example, does the medical representative ask for views about conducting a certain clinical trial at a project meeting after the protocol has been written and the investigator chosen?

Review. How are activities reviewed by managers at various levels in the company? How does the project group review its activities?

Priorities. How are priorities established and by whom? Are they in harmony at different levels of the company and between different departments at the same level?

Resources. How are resources allocated? How are conflicts handled? Conflict-of-interest issues are discussed separately in this chapter.

Commitment. What is the real commitment by senior managers to the project? Where does the project fit on the scale ranging from “no interest” to “vital for the company’s survival?”

Team assessment. Are members assessed by how well they represent their function as a sort of ambassador or by how well they push the project ahead within their discipline and meet their responsibilities? Are project members and leaders only assessed by line managers, or is there an additional assessment through the project system (i.e., by an appropriate manager of the matrix system)?

Project Style and Priority

Each project tends to develop its own style and rhythm after it has been operating for a period of time. This style is influenced by individuals on the team, the importance and nature of the drug being developed, and many other factors. There is often a striking difference between the project leader and line managers in how they view a particular project. Senior research and development managers must view the entire project portfolio and assign a priority and resources to each. Priorities may be given in an informal understanding or using a formal system. Many projects often receive a lower priority and fewer resources than the project group and project leader believe appropriate. This same discrepancy sometimes occurs at the corporate level, where the board of directors and/or Chief Executive Officer may not view the project portfolio or a selected project with the same degree of enthusiasm or caution as senior research and development managers. If this occurs, the reasons should be evaluated.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree