Chapter 16 Professional practice judgement artistry

INTRODUCTION

A reflective revolution is occurring in professional practice which requires knowledge beyond science to best provide quality client-centred professional services (Edwards et al 2004; Fulford et al 1996; Higgs & Titchen 2001a, b). In this revolution there is an increasing interest among various professions in challenging the hegemony of biomedical science and the medical model. There is growing support for a wellness orientation in care, and recognition of the unique blend of reasoning approaches which characterize and enrich health care (e.g. Edwards et al 2004, Mattingly & Fleming 1994). If we are to incorporate in practice the breadth of evidence that serves the interests of client/patient-centred care as well as evidence-based practice (which need not be mutually exclusive) then we need to address one of the greatest challenges facing the health professions today; that is, the need to make visible and credible the many invisible, tacit and as yet unexplored aspects of professional practice that are vital to the success of the professions.

This chapter reports on recent research (Paterson 2003, Paterson & Higgs 2001) that addressed this topic by focusing on the fusion of two such invisible and tacit aspects of advanced and expert practice: professional judgement and practice artistry. The construct professional practice judgement artistry (PPJA) was developed to name this merged skill.

PROFESSIONAL ARTISTRY IN PRACTICE

In client-centred health care we are seeing a significant trend to explore and embrace emerging literature (Eraut 1994, Fish 1998, Higgs & Titchen 2001c, Scott 1990, Titchen 2000) that acknowledges the value of artistry within professional practice, alongside science and humanism. Professional artistry is a uniquely individual view of practice within a shared tradition involving a blend of practitioner qualities, practice skills and creative imagination processes (Higgs & Titchen 2001c). It is concerned with ‘practical knowledge, skilful performance or knowing as doing’ (Fish 1998, p. 87) and is developed through the acquisition of a deep and relevant knowledge base and extensive experience (Beeston & Higgs 2001). Importantly, professional artistry does not negate research and theoretical knowledge or scientific evidence for practice; rather the professional artist practitioner uses such knowledge as a significant part of the range of knowledge (including experience-based knowledge) that serves as tools, input and a framework for clinical decision making.

PROFESSIONAL JUDGEMENT

Professional judgement refers to the ways in which practitioners interpret patients’ problems and issues and demonstrate saliency and concern in responding to these matters. It involves deliberate, conscious decision making and is associated with professional competence and judgements that reflect holistic discrimination, intuition and responsiveness reflective of proficient and expert performance (Dreyfus & Dreyfus 1986, p. 2). Judgement is both an action, the process of making evaluative decisions, and the product of these decisions. Health professionals constantly make judgements within, about and as a result of practice. We speak of making a judgement in much the same way as making a clinical decision, but with perhaps a greater emphasis, in judgement making, on the importance of higher level awareness, discrimination and evaluation in the face of the greyness (complexity) of professional practice due to its complexity, humanity, uncertainty and indeterminacy. If decision making in professional practice were entirely procedural and logical it could potentially be reduced to the realm of rules and manuals. However, from the viewpoint of PPJA, to be a professional and to provide professional services means that the client is receiving the benefit of extensive education and the capacity of the professional to make complex, situationally relevant judgements, utilizing a deep and broad store of professional knowledge. Skilled professionals are expected to have both propositional knowledge of the field and also experience-derived knowledge. Clients seek this blend of knowledge in the same way that they want technical competence as well as a depth of experience and artistry in refining these skills to address their unique needs.

OVERVIEW OF THE PPJA RESEARCH

A hermeneutic study (Paterson 2003) was conducted to investigate the question ‘How can the term judgement artistry be understood in relation to occupational therapy (OT) practice?’ The hermeneutic strategy, derived from the work of Gadamer and colleagues (Gadamer 1976, 1981; Gadamer et al 1988), was implemented as a hermeneutic spiral incorporating three hermeneutic strategies:

The text interpretation process involved repeated engagement with the texts, using these three strategies in the hermeneutic spiral. The researchers became deeply immersed in the texts, examining the parts or segments of the texts and then spiralling out to answer questions posed and reflect on the emerging whole or bigger picture of the phenomenon of PPJA being interpreted. Further details of the research strategy are presented in Paterson & Higgs (2005).

PPJA RESEARCH FINDINGS

A) PARTICIPANTS’ Understanding Of Judgement Artistry

An example of describing the therapist with PPJA as a cook came from one participant:

An educator said that a practitioner with PPJA is similar to:

B) DIMENSIONS OF PPJA

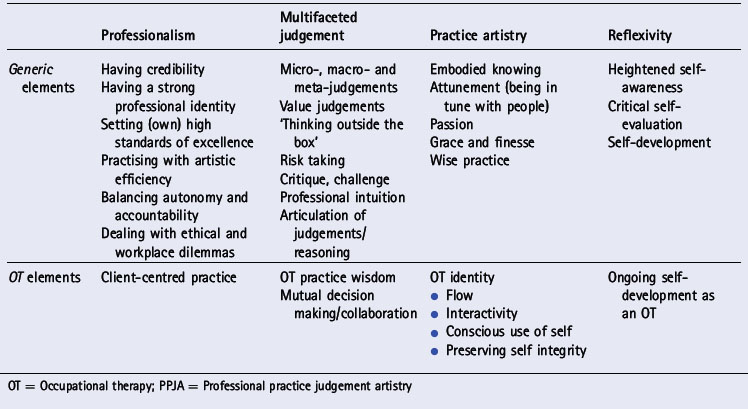

Four key dimensions of PPJA were identified: professionalism, multifaceted judgements, practice artistry and reflexivity (Table 16.1). Within these dimensions were a range of generic elements, some relevant across different professions and some specific to OT. In Table 16.1 the generic elements are so called because as researchers we found authenticity in these labels for many professions, in keeping with literature beyond OT that portrays professional artistry and practice wisdom (Scott 1990), and at multidisciplinary workshops and conferences where we received feedback on the applicability of these elements in other disciplines. More research in other disciplinary areas is required to investigate this question further and to develop other discipline-specific elements.

Professionalism

Professionalism is seen as an integral aspect of PPJA, as well as being the broader context for making high level/artistic professional/clinical judgements. That is, professionalism is a key ingredient of making sound judgements and demonstrating judgement artistry as well as being the overall framework within which professional practice occurs. Professionalism is portrayed by Eraut (1994) as an ideology, characterized by the traits and features of an ‘ideal type’ profession. Professionals are expected to practise with integrity and personal tolerance, to communicate effectively across language, cultural and situational barriers (Josebury et al 1990) and to demonstrate social responsibility (Prosser 1995), accountability and recognition of their limitations (Sultz et al 1984).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree