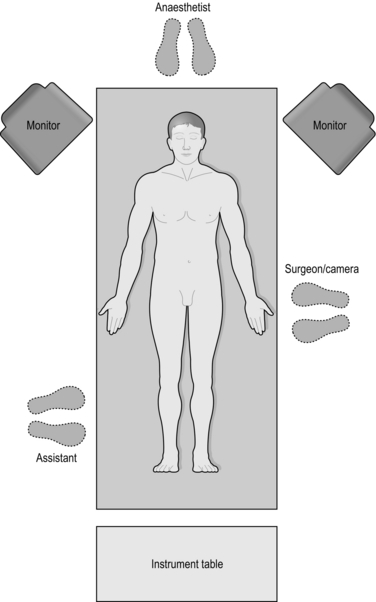

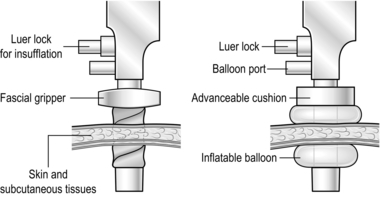

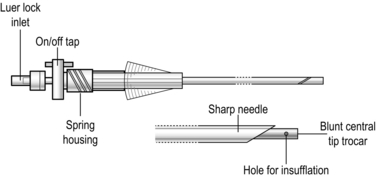

5 1. The aim of minimal access surgery is to cause the least anatomical, physiological and psychological trauma to the patient. 2. Patient expectations have moved with the new technology, leading to profound changes in patient selection, consent and management. 3. This chapter outlines the basic principles of laparoscopy. Almost all general surgical procedures can be performed with minimal access techniques. This includes surgeries involving the chest and pelvis. We shall describe them in detail under appropriate chapter headings (Table 5.1). Table 5.1 Examples of minimal access operations 4. Minimal access surgery has implications for hospital budgets. Capital equipment is expensive and requires updating at intervals. Consumables are particularly expensive and re-usage of disposable equipment is inadvisable. Theatre times are increased initially, although they decrease as surgeons gain experience. Short-stay and 5-day wards with rapid turnover reduce ‘hotel’ costs, free up main ward beds and help to reduce waiting lists. 5. The success of MAS is largely founded on the team based approached. Complicated procedures are performed with complex equipment that requires constant maintenance and upkeep. In addition, during a surgery, multiple intraoperative adjustments of the equipment (camera, monitors) are required which demand a skilled and collaborative theatre team that work in a coordinated fashion to ensure patient safety and excellent outcomes. Discuss Box 5.1 with PSV. 6. Increasing familiarity with the laparoscopic approach has led to its use in many situations previously contraindicated. Table 5.2 indicates common absolute and relative contraindications for laparoscopy. Table 5.2 Contraindications to laparoscopic surgery 1. Admission: Ideally plan admission for the day of surgery following appropriate investigation and work up. Evaluate patients to see if they can be managed on a day-case basis. 2. Consent: Obtain informed consent, including permission to convert to open surgery if necessary and quote a percentage probability. Warn patients about postoperative shoulder-tip pain and surgical emphysema. Always explain the commonly occurring risks, how they present and how they are managed. Explain the benefits of laparoscopic surgery, which include; small scars, quicker recovery and a reduction in post-operative pain. 3. Prophylaxis: Evaluate the thromboembolism risk and arrange prophylaxis accordingly (typically low-dose heparin and compression stockings). Prescribe prophylactic antibiotics if appropriate (e.g. biliary and bowel surgery). Bowel preparation is unnecessary except for some colorectal procedures. 4. Analgesia: Evaluate the likely postoperative analgesia requirements. Most anaesthetists avoid premedication in patients admitted on the day of surgery. Patients undergoing major laparoscopic procedures may still need opiates, albeit in reduced dosage. Their requirements may be further reduced by the use of intra-peritoneal local anaesthesia or abdominal wall nerve blocks. Patient-controlled analgesia (PCA) is appropriate following major procedures; however, for lesser procedures simple analgesics such as intravenous paracetamol, oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs and weak analgesics are usually effective. 5. Equipment: Make sure every member of the surgical team is fully familiar with the basic equipment for laparoscopy. 1. Laparoscopic theatre: Modern laparoscopic suites incorporate core equipment (monitor, insufflators, screens) within a mobile, ceiling-mounted console that can be maneouvred quickly to ensure rapid equipment adjustment throughout a procedure, ease of movement of the theatre staff, improved ergonomics and an efficient operating room. 2. Monitor: In the absence of an integrated theatre use a large monitor with high resolution screens. This can be mounted on mobile trolleys with a light source, insufflator and camera (Fig. 5.1). 3. Light source: Illumination of the image is dependent on the light cable and light source. Damage to the optical fibres in the cable will dull the light. Xenon or halogen bulbs are used to create high intensity light, however they also generate high heat which can injure the patient and surgeon through direct contact with the source or the tip of the light cable. Light is absorbed by blood, therefore in a situation of bleeding, the image can become dark quickly. 4. Insufflator: This delivers carbon dioxide from a high pressure cylinder at a high flow rate but a low accurately controlled pressure, to create the pneumoperitoneum. Ensure that it is positioned within your view so that you can monitor the pressures and flows. Familiarity in changing the gas cylinder is important as cylinders may empty at a critical point in surgery, with loss of pneumoperitoneum as a result. 5. Camera: The video camera head, either a single chip or a superior three-chip instrument, is attached to the laparoscope to form an electrical–optic interface. The camera is connected by cable to a video processor, which interprets and modifies the signal and transmits it to the monitors. Most systems incorporate a ‘white balance’ function, which can be calibrated to represent colours accurately. Some newer camera systems dispense with the laparoscope by placing the microchip on the end of a 10-mm rod (chip-on-a-stick). 6. Laparoscope: The standard laparoscope measures 24 cm in length and contains a series of quartz optical rods and focusing lenses that conduct the image to the eyepiece. The telescope can have a flat end with a straight on view (0 degree) or can be angled with an oblique view (30 or 45 degree). The 30 degree scope can provide a much greater fieldview compared to the 0 degree scope. The telescopes can vary in diameter from a 5 mm to a 10 mm (the latter providing the brighter image and more visual acuity). The 10 mm 30 degree telescope is used for most procedures. 7. Suction/irrigation is performed usually through a disposable or reusable 5-mm instrument. The hand piece is connected to a pressurized reservoir of warm saline as well as the suction. Both are controllable by buttons on the hand piece. The disposable instruments tend to be more ergonomic and often come with a mechanical irrigation feed. 8. Ports provide passages through which to insert instruments, which can be disposable or reusable. The more expensive disposable ports have the advantage of being more ergonomic (Greek: ergon = work + nemein = to manageable: easy to use) as well as being radiolucent and sterile. They may have blunt ends for open induction of pneumoperitoneum or be fitted with a sharp, spring-loaded trocar with a plastic guard that projects beyond the point as soon as the trocar enters the peritoneal cavity. Some of the blunt ended ports are designed so that the tip expands rather than divides while passing through abdominal wall structures. Ports are presented in a range of sizes to accommodate various instruments. Large ports can be fitted with ‘sizers’ to reduce the lumen. Alternatively, some disposable large ports have an inbuilt diaphragm permitting the introduction of a number of instrument diameters without loss of pneumoperitoneum. All have attachments to allow insufflation, and valves to prevent gas leaks. Some have collars, allowing them to be secured in position (Fig. 5.2). It is good practice to rehearse port requirements for specific procedures with the surgical team. This ensures appropriate port availability and avoids the expense of opening unnecessary disposable ports. 9. Instruments: Laparoscopic instruments come in a standard length (30 cm long shaft). However, bariatric surgeries require longer instruments (45 cm in length). Most instruments come in a variety of handles with different locking handles. Instruments can be wholly disposable or reusable but may also be a combination of a reusable hand piece/shaft with a disposable tip. Many reusable instruments are of a modular design with separate hand pieces and shafts (Box 5.2). In any specific procedure a variety of types may be in use. Instrument selection is often dictated by a number of factors, which include procedure-specific requirements, personal preference and cost. Most surgical units possess a number of identical basic trays of non-disposable instruments for laparoscopic procedures. Multidisciplinary input from the surgical and scrub teams is important when there is an opportunity to influence the specification of such trays. Since disposables are expensive, either specify which ones are required beforehand or ensure that they are opened only when needed. A combination of reusable and disposable items (ports and instruments) are usually required. Consider incorporating a range of dissectors from those available, such as Maryland, Mixter. 10. Anaesthesia: General anaesthesia is usually augmented with muscle relaxation, intubation and ventilation so that a pneumoperitoneum can be induced without causing cardiorespiratory embarrassment. Abdominal distension affects venous return, heart rate and consequently blood pressure. A profound bradycardia is not uncommon even in fit individuals, particularly on induction of the pneumoperitoneum. Abdominal distension also affects chest-wall compliance and the ease with which patients can be ventilated. Aim to use the lowest pre-set intra-abdominal pressure compatible with adequate surgical exposure.

Principles of minimal access surgery

GENERAL PRINCIPLES OF LAPAROSCOPY

Basic

Advanced

Diagnostic laparoscopy

Cholecystectomy

Appendicecomy

Hernia repair

Adhesiolysis

Arthroscopy

Nissen fundoplication

Repair of perforated duodenal ulcer

Heller’s serocardiomyotomy

Gastrectomy

Hepatectomy

Adrenalectomy

Splenectomy

Nephrectomy

Oophorectomy

Hysterectomy

Prostatectomy

Absolute contraindications

Relative contraindications

Generalized peritonitis

Gross obesity. Simple overweight is no contraindication; such patients suffer less from postoperative respiratory complications than they would following open operation

Intestinal obstruction

Pregnancy

Major clotting abnormalities

Multiple abdominal adhesions. Provided the first instrument port is inserted by an open technique, laparoscopy can be safely performed on patients with moderate adhesions following, for example, previous surgery

Liver cirrhosis/portal hypertension

Organomegaly (enlarged liver or spleen)

Failure to tolerate general anaesthesia

Abdominal aortic aneurysm

Uncontrolled shock

Patient refusal

Preparation

Basic laparoscopic equipment (excluding instruments)

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Principles of minimal access surgery