20 Prevention of Infectious Diseases

I Overview of Infectious Disease

Humans have coexisted with microbes since the beginning of the human race. One of the originators of epidemiology, John Snow, laid the foundations of the discipline by analyzing and controlling cholera, a bacterial disease caused by Vibrio cholerae. Immunity to infection is influenced by a person’s genetic background, overall health, access to good sanitation and nutrition, and even social status. Therefore, the prevalence of infectious diseases is a good proxy for disenfranchisement and poverty in a population. Poverty plays multiple roles in the cycle of infectious diseases. Poverty can contribute to infectious diseases by making the environment more suitable for disease transmission, and poverty can also be a consequence of infectious diseases. Causal pathways include complications of pregnancy, repeated episodes of diarrheal illness in children leading to slowed mental and physical development, and the death of broad swaths of a parent generation (e.g., from AIDS).1

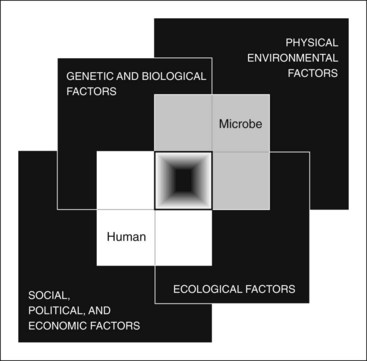

Control of infectious disease is challenging because of the adaptive capabilities of microbes. Microbes have inhabited the earth far longer than humans and have successfully adapted to all evolutionary challenges. Several recent developments fuel a global environment in which new infectious diseases emerge and become rooted in society, as summarized by the Institute of Medicine into the convergence model2 (Fig. 20-1; see also Chapter 30). The convergence model is centered on the human-microbe interaction. The black box in the center of the figure indicates that these interactions can be difficult to predict in an emerging disease. More importantly, a microbe is a necessary but not sufficient cause of ill health. Humans constantly encounter millions of potentially harmful microbes without falling ill. Four domains of factors impact humans and microbes or their interactions. Each of these factors provides a starting point for thinking systematically about pathways of prevention (Box 20-1).

Figure 20-1 Convergence model of human-microbe interaction.

(From Smolinski MS, Hamburg MA, Lederberg J, editors: Microbial threats to health: emergence, detection, and response, Washington, DC, 2003, National Academies Press.)

Box 20-1 Four Domains of Human-Microbe Interaction

Pathways in Prevention of Infectious Disease

3 Ecological Factors

Changes in ecosystems can effect the transmission of microbes through water, soil, air, food, or vectors. Such alterations also affect microbes with animal reservoirs. Examples include the changes of malaria prevalence in response to a warming climate and the increase in prevalence of Lyme disease because of more deer in expanding New England woods. Also important are changes in land use. A growing number of emerging infectious diseases arise from increased human contact with animal reservoirs (disruption/destabilization of natural habitats; see Chapter 30). An example is the Nipah virus, which was endemic to Southeast Asian fruit bats. When pig farms grew in size and density and expanded into fruit orchards in the late 1990s, the virus was transmitted to the pigs and then their handlers, causing encephalitis outbreaks. Pathways to prevention in this domain can be again found mainly through surveillance.

4 Social, Political, and Economic Factors

Pathways for prevention through social, economic, and political factors lie in taking a comprehensive view of health, advocating for improvements to the underlying determinants in populations, and helping create the political will to strengthen public health and overcome health disparities (see Chapter 26).

Understanding and controlling infectious diseases requires integrating many different preventive and public health skills. These include obtaining accurate history on sensitive topics such as sexual behaviors; geographic epidemiology; outbreak investigation; analysis of disease rates by different variables (age, gender, race, socioeconomic status) to detect high-risk groups; successful outreach to public and health professionals; screening; contact tracing; immunization; school health; counseling; sanitation; waste and wastewater management; food protection; disease registries; and prophylactic drugs. Diseases vary, but the epidemiologic skills are similar for different diseases, independent of their mode of transmission (e.g., STD vs. vector-borne disease). Public health controls disease through prevention efforts in three broad categories, as follows2:

Improving resistance of the host. Includes such basics as hygiene and nutrition, as well as vaccination, postexposure prophylaxis, and chemoprophylaxis (see Chapter 15).

Improving resistance of the host. Includes such basics as hygiene and nutrition, as well as vaccination, postexposure prophylaxis, and chemoprophylaxis (see Chapter 15).

Improving environmental safety. Includes sanitation, air quality control, water and food safety, and control of vectors and animal reservoirs. Public sanitation has been crucial in controlling infectious disease. Worldwide, areas without access to clean water and basic sanitation carry the highest burden of diseases that disproportionally impact children less than 5 years old.

Improving environmental safety. Includes sanitation, air quality control, water and food safety, and control of vectors and animal reservoirs. Public sanitation has been crucial in controlling infectious disease. Worldwide, areas without access to clean water and basic sanitation carry the highest burden of diseases that disproportionally impact children less than 5 years old.

Improving public health systems. Includes improved contact tracing, education, containment, and herd immunity.

Improving public health systems. Includes improved contact tracing, education, containment, and herd immunity.

All infection control activity requires a thorough understanding of the various infectious diseases. This chapter only briefly addresses the complexity of different diseases, and important diseases are discussed elsewhere (e.g., see Chapter 3 for influenza and Select Readings for further information). On the other hand, control of an infectious disease often only requires understanding how it is transmitted. For example, John Snow determined that water from a particular company caused most of the cholera in London. Armed with this understanding and the supporting data, he was able to convince the local council to disable the well. Breaking the chain of transmission helped end the outbreak.

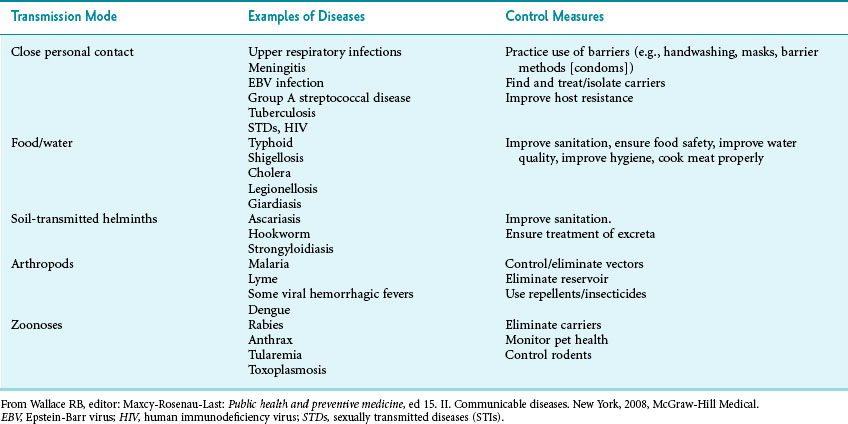

Diseases can be usefully grouped according to transmission3 (Table 20-1). Often, surveys of patients and “shoe leather” epidemiology will reveal the mode of transmission, and public health officials can disrupt disease transmission before the causative agent has been identified (see Chapter 3).

A Burden of Disease

Infectious diseases affect all countries, but the burden of disease is different in developed and developing countries. In the United States, infectious disease mortality has for the most part steadily declined since the early 1900s.4 Most of this decline preceded the availability of antibiotics or vaccines and was likely the result of better hygiene, sanitation, and chlorination of drinking water.

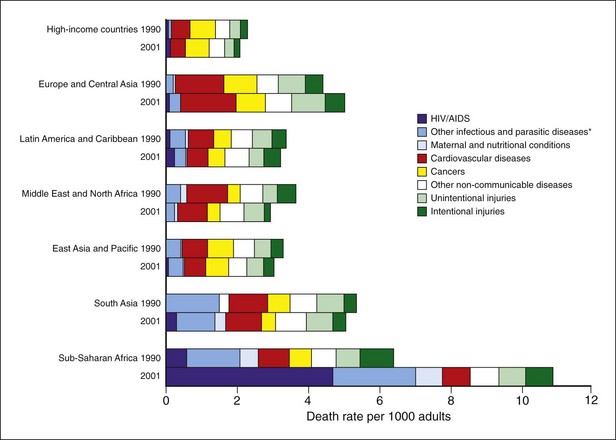

To weigh the effects of disease on life span, many global health experts measure the impact of infectious disease in disability-adjusted life years (DALY). DALY take into account premature mortality and years of life lived in less than full health (see Chapter 24.) Five of the 10 leading diseases for global disease burden are infectious: HIV/AIDS, lower respiratory infections, diarrheal illnesses, malaria, and tuberculosis (TB). More importantly, many of the infectious diseases causing a large disease burden are increasing (HIV/AIDS, respiratory diseases) and are disproportionately impacting the lowest-income countries.5

See online Figure 20-2 on studentconsult.com for global mortality rates by cause and region. ![]()

Figure 20-2 Global death rates by disease group and region.

*Includes respiratory infections. Cause-specific estimated death rates for 1990 might not be completely comparable to those for 2001 because of changes in data availability and methods, plus some approximations in mapping 1990 estimates to the 2001 regions of East Asia and Pacific, South Asia, and Europe and Central Asia. For all geographic regions, high-income countries are excluded and shown as single group at top of graph. Therefore the “geographic regions” refer only to low-income and middle-income countries.

(From Lopez AD et al: Lancet 367:1747–1757, 2006.)

B Obtaining an Accurate History

More often, patients may be embarrassed by behavior that induced the infectious disease. Examples range from people kissing their pets (leading to transmission of Pasteurella spp.6) to sexual behaviors and use of illicit drugs (leading to transmission of sexually transmitted and blood-borne diseases). Patients may not be comfortable sharing such information unless the clinician is skilled at putting people at ease and asks about intimate details in a nonjudgmental way. Taking such a history is crucial for understanding how the patient contracted the infectious disease and who else may have been infected.

Client-centered counseling means tailoring prevention messages to a patient’s practices, values, and risk perceptions. For sexually transmitted diseases (STDs), or sexually transmitted infections (STIs), client-centered counseling has been shown to increase the likelihood of patients changing their behavior.7 The same likely holds true for other behaviors. As in other areas of counseling, it is important that the clinician start with open-ended questions and reassure the patient that the information will be treated confidentially.

For adolescents, “Now I am going to take a few minutes to ask you some sensitive questions that are important for me to help you be healthy. Anything we discuss will be completely confidential. I won’t discuss this with anyone, not even your parents, without your permission.”8 After clarifying this, introduce the topic in a nonthreatening way: “Some of my patients your age have started having sex. Have you had sex?”

For adolescents, “Now I am going to take a few minutes to ask you some sensitive questions that are important for me to help you be healthy. Anything we discuss will be completely confidential. I won’t discuss this with anyone, not even your parents, without your permission.”8 After clarifying this, introduce the topic in a nonthreatening way: “Some of my patients your age have started having sex. Have you had sex?”

For adults, “To provide the best care, I ask all my patients about their sexual activity. So, tell me about your sex life.”

For adults, “To provide the best care, I ask all my patients about their sexual activity. So, tell me about your sex life.”

Further history taking can follow the model of the “5 Ps” (partners, prevention of pregnancy, protection from STDs, practices, and past STDs).7

Further history taking can follow the model of the “5 Ps” (partners, prevention of pregnancy, protection from STDs, practices, and past STDs).7

For each of those domains, again it is important to start with open-ended questions (e.g., “Tell me about how you have sex”; “Where do you meet your partners?”) before asking about specific high-risk behaviors.

For each of those domains, again it is important to start with open-ended questions (e.g., “Tell me about how you have sex”; “Where do you meet your partners?”) before asking about specific high-risk behaviors.

Additional information on effective STD counseling and behavioral interventions can be found online.9

II Public Health Priorities

A HIV/AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria

In some countries in sub-Saharan Africa, HIV/AIDS, tuberculosis, and malaria together account for more than 50% of deaths.10 These illnesses decrease health and constrain growth and development of many of the poorest nations. In general, they also impact developed countries, either internally through income inequality or externally through immigration and international travel. All these diseases have important lessons to offer for successful infectious disease prevention. Prevention efforts for these three diseases are often implemented together, as through the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, Tuberculosis, and Malaria.11 The Global Fund follows an innovative model, targeting all three diseases through partnerships among government, civil society, the private sector (including businesses and foundations), and affected communities, combined with meticulous attention to data and evaluation.

1 Human Immunodeficiency Virus/Acquired Immunodeficiency Syndrome

Epidemiology

No new disease in modern times has had as severe an impact worldwide as AIDS, which is caused by the human immunodeficiency virus. Although HIV transmission and management are of major concern in the United States, the situation is more serious in Southeast Asia, South America, Russia, and the Indian subcontinent. It is catastrophic in sub-Saharan Africa, where many adults are infected, death rates in the most productive age groups are extremely high, and many children have been orphaned. In 2009 an estimated 2.6 million people became newly infected with HIV, with 1.8 million deaths worldwide.12

The U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) estimated in 2012 that more than 1 million people are living with HIV infection in the United States, with around 18,000 deaths annually. An estimated 50,300 Americans are newly infected with HIV each year;13 one in five people (21%) living with HIV are unaware of having the infection, presumably accounting for a large proportion of new infections.

Prevention of HIV Infection and AIDS

The best ways to prevent the spread of HIV/AIDS have been known since the syndrome was discovered and before the responsible microorganism was identified. They consist of restricting sexual activity to a monogamous relationship and avoiding IDU. If a person chooses to have multiple sexual partners or to use intravenous drugs, the next best prevention is to use condoms for every sexual contact and clean needles and equipment for each IDU episode. Male circumcision, antiretroviral therapy (ART) and possibly also antiretroviral vaginal gel can also significantly decrease infection rates.14 Treatment is prevention (see below).

Globally, an unprecedented coalition of governments, nongovernmental organizations (NGOs), pharmaceutical companies, and private foundations have worked together successfully to control the spread of the AIDS epidemic. Through these efforts, the annual number of new HIV infections has declined worldwide, and AIDS-related deaths have fallen with increased access to ART. In 33 countries (22 in sub-Saharan Africa) the HIV incidence decreased more than 25% between 2001 and 2009.15 These successes highlight the following lessons about prevention and disease control in general:

1. Prevention and treatment exist along a continuum. HIV prevention efforts have included access for people to ART. Politically, it is difficult to generate support for case finding and prevention if diagnosed patients cannot be treated.

2. Knowledge is essential to successful prevention but not enough; motivations and behavior need to change as well. The most successful ways to impact behavior are to provide motivation and to change social norms.

3. Successful prevention targets clusters of behavioral indicators, not just one. Countries that simultaneously targeted condom use, delayed initiation of sexual activity, and reducing multiple partnerships had marked reductions in HIV prevalence.

4. Target high-risk populations. In most countries, a minority of the population has multiple sexual partners or has commercial or transactional sex (sex for drugs, food, or shelter). Targeting prevention efforts to these groups has a much higher impact on population health than does general prevention.

5. Empowerment is part of prevention. Many of the primary transmitters of HIV infection come from vulnerable and disempowered populations. Prevention programs combining outreach and empowerment with modification of sexual behavior have shown impressive results in South Africa and India.

The CDC recommends routine, voluntary, opt-out HIV screening for all patients age 13 to 64 in health care settings, unless prevalence of undiagnosed HIV infection has been documented at less than 0.1%.16 Box 20-2 provides additional CDC guidelines.16,17

Box 20-2 CDC Guidelines for HIV/AIDS Screening

Screening all patients starting treatment for tuberculosis and all patients seeking treatment for sexually transmitted diseases/infections (STDs/STIs).

Repeat screening at least annually of all persons at high risk for human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection:

Counseling of patients that they and their prospective sex partners to be tested before initiating a new sexual relationship.

Routine, voluntary, opt-out testing of all pregnant women.

Repeat testing during the third trimester:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree