EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If generalized pallor suddenly develops, quickly look for signs of shock, such as tachycardia, hypotension, oliguria, and a decreased level of consciousness (LOC). Prepare to rapidly infuse fluids or blood. Obtain a blood sample for hemoglobin and serum glucose levels and hematocrit. Keep emergency resuscitation equipment nearby.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient’s condition permits, take a complete history. Does the patient or anyone in his family have a history of anemia or of a chronic disorder that might lead to pallor, such as renal failure, heart failure, or diabetes? Ask about the patient’s diet, particularly his intake of red meat and green vegetables.

Then, explore the pallor more fully. Find out when the patient first noticed it. Is it constant or intermittent? Does it occur when he’s exposed to the cold? Does it occur when he’s under emotional stress? Explore associated signs and symptoms, such as dizziness, fainting, orthostasis, weakness and fatigue on exertion, dyspnea, chest pain, palpitations, menstrual irregularities, or loss of libido. If pallor is confined to one or both legs, ask the patient if walking is painful. Do his legs feel cold or numb? If pallor is confined to his fingers, ask about tingling and numbness.

Start the physical examination by taking the patient’s vital signs. Make sure to check for orthostatic hypotension. Auscultate the heart for gallops and murmurs and the lungs for crackles. Check the patient’s skin temperature — cold extremities commonly occur with vasoconstriction or arterial occlusion. Also, note skin ulceration. Examine the abdomen for splenomegaly. Finally, palpate peripheral pulses. An absent pulse in a pale extremity may indicate arterial occlusion, whereas a weak pulse may indicate low cardiac output.

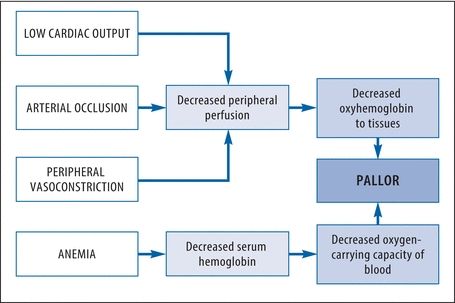

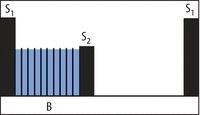

How Pallor Develops

Pallor may result from decreased peripheral oxyhemoglobin or decreased total oxyhemoglobin. The chart below illustrates the progression to pallor.

Medical Causes

- Anemia. Typically, pallor develops gradually with anemia. The patient’s skin may also appear sallow or grayish. Other effects include fatigue, dyspnea, tachycardia, a bounding pulse, an atrial gallop, a systolic bruit over the carotid arteries and, possibly, crackles and bleeding tendencies.

- Arterial occlusion (acute). Pallor develops abruptly in the extremity with arterial occlusion, which usually results from an embolus. A line of demarcation develops, separating the cool, pale, cyanotic, and mottled skin below the occlusion from the normal skin above it. Accompanying pallor may be severe pain, intense intermittent claudication, paresthesia, and paresis in the affected extremity. Absent pulses and an increased capillary refill time below the occlusion are also characteristic.

- Arterial occlusive disease (chronic). With arterial occlusive disease, pallor is specific to an extremity — usually one leg, but occasionally, both legs or an arm. It develops gradually from obstructive arteriosclerosis or a thrombus and is aggravated by elevating the extremity. Associated findings include intermittent claudication, weakness, cool skin, diminished pulses in the extremity and, possibly, ulceration and gangrene.

- Frostbite. Pallor is localized to the frostbitten area, such as the feet, hands, or ears. Typically, the area feels cold, waxy and, perhaps, hard in deep frostbite. The skin doesn’t blanch, and sensation may be absent. As the area thaws, the skin turns purplish blue. Blistering and gangrene may then follow if the frostbite is severe.

- Orthostatic hypotension. With orthostatic hypotension, pallor occurs abruptly on rising from a recumbent position to a sitting or standing position. A precipitous drop in blood pressure, an increase in heart rate, and dizziness are also characteristic. At times, the patient loses consciousness for several minutes.

- Raynaud’s disease. Pallor of the fingers upon exposure to cold or stress is a hallmark of Raynaud’s disease. Typically, the fingers abruptly turn pale and then cyanotic; with rewarming, they become red and paresthetic. With chronic disease, ulceration may occur.

- Shock. Two forms of shock initially cause an acute onset of pallor and cool, clammy skin. With hypovolemic shock, other early signs and symptoms include restlessness, thirst, slight tachycardia, and tachypnea. As shock progresses, the skin becomes increasingly clammy, the pulse becomes more rapid and thready, and hypotension develops with narrowing pulse pressure. Other signs and symptoms include oliguria, a subnormal body temperature, and a decreased LOC. With cardiogenic shock, the signs and symptoms are similar but usually more profound.

Special Considerations

If the patient has chronic generalized pallor, prepare him for blood studies and, possibly, bone marrow biopsy. If the patient has localized pallor, he may require arteriography or other diagnostic studies to accurately determine the cause.

When pallor results from low cardiac output, administer blood and fluids as well as a diuretic, a cardiotonic, and an antiarrhythmic as needed. Frequently monitor the patient’s vital signs, intake and output, electrocardiogram results, and hemodynamic status.

Patient Counseling

For anemia, explain the importance of an iron-rich diet and rest. For frostbite and Raynaud’s disease, discuss cold protection measures. For orthostatic hypotension, explain the need to rise slowly. Discuss signs and symptoms to report.

Pediatric Pointers

In children, pallor stems from the same causes as it does in adults. It can also stem from a congenital heart defect or chronic lung disease.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Palpitations

Defined as a conscious awareness of one’s heartbeat, palpitations are usually felt over the precordium or in the throat or neck. The patient may describe them as pounding, jumping, turning, fluttering, or flopping or as missing or skipping beats. Palpitations may be regular or irregular, fast or slow, and paroxysmal or sustained.

Although usually insignificant, palpitations may result from a cardiac or metabolic disorder and from the effects of certain drugs. Nonpathologic palpitations may occur with a newly implanted prosthetic valve because the valve’s clicking sound heightens the patient’s awareness of his heartbeat. Transient palpitations may accompany emotional stress (such as fright, anger, or anxiety) or physical stress (such as exercise and fever). They can also accompany the use of stimulants, such as tobacco and caffeine.

To help characterize the palpitations, ask the patient to simulate their rhythm by tapping his finger on a hard surface. An irregular “skipped beat” rhythm points to premature ventricular contractions, whereas an episodic racing rhythm that ends abruptly suggests paroxysmal atrial tachycardia.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient complains of palpitations, ask him about dizziness and shortness of breath. Then, inspect for pale, cool, clammy skin. Take the patient’s vital signs, noting hypotension and an irregular or abnormal pulse. If these signs are present, suspect cardiac arrhythmia. Prepare to begin cardiac monitoring and, if necessary, to deliver electroshock therapy. Start oxygen therapy via a mask or nasal cannula. Begin an I.V. line to administer an antiarrhythmic, if needed.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in distress, perform a complete cardiac history and physical examination. Ask if he has a cardiovascular or pulmonary disorder, which may produce arrhythmias. Does the patient have a history of hypertension or hypoglycemia? Make sure to obtain a drug history. Has the patient recently started cardiac glycoside therapy? Also, ask about caffeine, tobacco, and alcohol consumption.

Then, explore associated symptoms, such as weakness, fatigue, and angina. Finally, auscultate for gallops, murmurs, and abnormal breath sounds.

Medical Causes

- Anxiety attack (acute). Anxiety is the most common cause of palpitations in children and adults. With this disorder, palpitations may be accompanied by diaphoresis, facial flushing, trembling, and an impending sense of doom. Almost invariably, patients hyperventilate, which may lead to dizziness, weakness, and syncope. Other typical findings include tachycardia, precordial pain, shortness of breath, stomach ache, diarrhea, restlessness, and insomnia.

- Cardiac arrhythmias. Paroxysmal or sustained palpitations may be accompanied by dizziness, weakness, and fatigue. The patient may also experience an irregular, rapid, or slow pulse rate; decreased blood pressure; confusion; pallor; oliguria; and diaphoresis.

- Hypertension. With hypertension, the patient may be asymptomatic or may complain of sustained palpitations alone or with a headache, dizziness, tinnitus, and fatigue. His blood pressure typically exceeds 140/90 mm Hg. He may also experience nausea and vomiting, seizures, and a decreased level of consciousness.

- Hypocalcemia. Typically, hypocalcemia produces palpitations, weakness, and fatigue. It progresses from paresthesia to muscle tension and carpopedal spasms. The patient may also exhibit muscle twitching, hyperactive deep tendon reflexes, chorea, and positive Chvostek’s and Trousseau’s signs.

- Mitral prolapse. Mitral prolapse is a valvular disorder that may cause paroxysmal palpitations accompanied by sharp, stabbing, or aching precordial pain. The hallmark of this disorder, however, is a midsystolic click followed by an apical systolic murmur. Associated signs and symptoms may include dyspnea, dizziness, severe fatigue, a migraine headache, anxiety, paroxysmal tachycardia, chest pain, crackles, and peripheral edema.

- Mitral stenosis. Early features of mitral stenosis typically include sustained palpitations accompanied by exertional dyspnea and fatigue. Auscultation also reveals a loud S1 or opening snap and a rumbling diastolic murmur at the apex. Patients may also experience related signs and symptoms, such as an atrial gallop and, with advanced mitral stenosis, orthopnea, dyspnea at rest, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, peripheral edema, jugular vein distention, ascites, hepatomegaly, and atrial fibrillation.

- Thyrotoxicosis. A characteristic symptom of thyrotoxicosis, sustained palpitations may be accompanied by tachycardia, dyspnea, weight loss despite increased appetite, diarrhea, tremors, nervousness, diaphoresis, heat intolerance and, possibly, exophthalmos and an enlarged thyroid. The patient may also experience an atrial or a ventricular gallop.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Palpitations may result from drugs that precipitate cardiac arrhythmias or increase cardiac output, such as cardiac glycosides; sympathomimetics, such as cocaine; ganglionic blockers; beta-adrenergic blockers; calcium channel blockers; atropine; and minoxidil.

HERB ALERT

HERB ALERT

Herbal remedies, such as ginseng, may cause adverse reactions, including palpitations and an irregular heartbeat.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as an electrocardiogram and Holter’s monitoring. Remember that even mild palpitations can cause the patient much concern. Maintain a quiet, comfortable environment to minimize anxiety and perhaps decrease palpitations.

Patient Counseling

Explain diagnostic tests the patient needs, and teach him ways to reduce anxiety.

Pediatric Pointers

Palpitations in children commonly result from a fever and congenital heart defects, such as patent ductus arteriosus and septal defects. Because many children can’t describe this complaint, focus your attention on objective measurements, such as cardiac monitoring, physical examination, and laboratory tests.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Papular Rash

A papular rash consists of small, raised, circumscribed — and perhaps discolored (red to purple) — lesions known as papules. It may erupt anywhere on the body in various configurations and may be acute or chronic. Papular rashes characterize many cutaneous disorders; they may also result from allergy and from infectious, neoplastic, and systemic disorders. (To compare papules with other skin lesions, see Recognizing Common Skin Lesions.)

History and Physical Examination

Your first step is to fully evaluate the papular rash: note its color, configuration, and location on the patient’s body. Find out when it erupted. Has the patient noticed changes in the rash since then? Is it itchy or burning, or painful or tender? Has there ever been discharge or drainage from the rash? If so, have the patient describe it. Also, have him describe associated signs and symptoms, such as fevers, headaches, and GI distress.

Next, obtain a medical history, including allergies; previous rashes or skin disorders; infections; childhood diseases; sexual history, including sexually transmitted diseases; and cancers. Has the patient recently been bitten by an insect or rodent or been exposed to anyone with an infectious disease? Finally, obtain a complete drug history.

Medical Causes

- Acne vulgaris. With acne vulgaris, rupture of enlarged comedones produces inflamed — and perhaps, painful and pruritic — papules, pustules, nodules, or cysts on the face and sometimes the shoulders, chest, and back.

- Anthrax (cutaneous). Anthrax is an acute infectious disease caused by the gram-positive, spore-forming bacterium Bacillus anthracis. The disease can occur in humans exposed to infected animals, tissue from infected animals, or biological warfare. Cutaneous anthrax occurs when the bacterium enters a cut or abrasion on the skin. The infection begins as a small, painless, or pruritic macular or papular lesion resembling an insect bite. Within 1 to 2 days, it develops into a vesicle and then a painless ulcer with a characteristic black, necrotic center. Lymphadenopathy, malaise, a headache, or a fever may develop.

- Dermatomyositis. Gottron’s papules — flat, violet-colored lesions on the dorsa of the finger joints and the nape of the neck and shoulders — are pathognomonic of dermatomyositis, as is the dusky lilac discoloration of periorbital tissue and lid margins (heliotrope edema). These signs may be accompanied by a transient, erythematous, macular rash in a malar distribution on the face and sometimes on the scalp, forehead, neck, upper torso, and arms. This rash may be preceded by symmetrical muscle soreness and weakness in the pelvis, upper extremities, shoulders, neck and, possibly, the face (polymyositis).

- Follicular mucinosis. With follicular mucinosis, perifollicular papules or plaques are accompanied by prominent alopecia.

- Fox-Fordyce disease. Fox-Fordyce disease is a chronic disorder that’s marked by pruritic papules on the axillae, pubic area, and areolae associated with apocrine sweat gland inflammation. Sparse hair growth in these areas is also common.

- Granuloma annulare. Granuloma annulare is a benign, chronic disorder that produces papules that usually coalesce to form plaques. The papules spread peripherally to form a ring with a normal or slightly depressed center. They usually appear on the feet, legs, hands, or fingers and may be pruritic or asymptomatic.

- Human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection. Acute infection with the HIV retrovirus typically causes a generalized maculopapular rash. Other signs and symptoms include a fever, malaise, a sore throat, and a headache. Lymphadenopathy and hepatosplenomegaly may also occur. Most patients don’t recall these symptoms of acute infection.

- Kaposi’s sarcoma. Kaposi’s sarcoma is characterized by purple or blue papules or macules of vascular origin on the skin, mucous membranes, and viscera. These lesions decrease in size with firm pressure and then return to their original size within 10 to 15 seconds. They may become scaly and ulcerate with bleeding.

Multiple variants of Kaposi’s sarcoma are known; most individuals are immunocompromised in some way, especially those with HIV or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome. Human herpes virus 8 has been strongly implicated as a cofactor in the development of Kaposi’s sarcoma.

- Kawasaki disease. Patients with Kawasaki disease have a distinct erythematous maculopapular rash, usually on the trunk and the extremities. Accompanying symptoms include high fever, irritability, red eyes, bright red cracked lips, a strawberry tongue, swollen hands and feet, peeling skin on the fingertips and toes, and cervical lymphadenopathy. More severe complications include coronary artery abnormalities.

- Lichen planus. Discrete, flat, angular or polygonal, violet papules, commonly marked with white lines or spots, are characteristic of lichen planus. The papules may be linear or coalesce into plaques and usually appear on the lumbar region, genitalia, ankles, anterior tibiae, and wrists. Lesions usually develop first on the buccal mucosa as a lacy network of white or gray threadlike papules or plaques. Pruritus, distorted fingernails, and atrophic alopecia commonly occur.

- Mononucleosis (infectious). A maculopapular rash that resembles rubella is an early sign of mononucleosis in 10% of patients. The rash is typically preceded by a headache, malaise, and fatigue. It may be accompanied by a sore throat, cervical lymphadenopathy, and fluctuating temperature with an evening peak of 101°F to 102°F (38.3°C to 38.9°C). Splenomegaly and hepatic inflammation may also develop.

- Necrotizing vasculitis. With necrotizing vasculitis, crops of purpuric, but otherwise asymptomatic, papules are typical. Some patients also develop a low-grade fever, a headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and abdominal pain.

- Pityriasis rosea. Pityriasis rosea begins with an erythematous “herald patch” — a slightly raised, oval lesion about 2 to 6 cm in diameter that may appear anywhere on the body. A few days to weeks later, yellow to tan or erythematous patches with scaly edges appear on the trunk, arms, and legs, commonly erupting along body cleavage lines in a characteristic “pine tree” pattern. These patches may be asymptomatic or slightly pruritic, are 0.5 to 1 cm in diameter, and typically improve with skin exposure.

- Polymorphic light eruption. Abnormal reactions to light may produce papular, vesicular, or nodular rashes on sun-exposed areas. Other symptoms include pruritus, a headache, and malaise.

- Psoriasis. Psoriasis is a common chronic disorder that begins with small, erythematous papules on the scalp, chest, elbows, knees, back, buttocks, and genitalia. These papules are sometimes pruritic and painful. Eventually, they enlarge and coalesce, forming elevated, red, scaly plaques covered by characteristic silver scales, except in moist areas such as the genitalia. These scales may flake off easily or thicken, covering the plaque. Associated features include pitted fingernails and arthralgia.

- Rosacea. Rosacea is a hyperemic disorder characterized by persistent erythema, telangiectasia, and recurrent eruption of papules and pustules on the forehead, malar areas, nose, and chin. Eventually, eruptions occur more frequently and erythema deepens. Rhinophyma may occur in severe cases.

- Seborrheic keratosis. With seborrheic keratosis, a cutaneous disorder, benign skin tumors begin as small, yellow-brown papules on the chest, back, or abdomen, eventually enlarging and becoming deeply pigmented. However, in blacks, these papules may remain small and affect only the malar part of the face (dermatosis papulosa nigra).

- Smallpox (variola major). Initial signs and symptoms of smallpox include a high fever, malaise, prostration, a severe headache, a backache, and abdominal pain. A maculopapular rash develops on the mucosa of the mouth, pharynx, face, and forearms and then spreads to the trunk and legs. Within 2 days, the rash becomes vesicular and later pustular. The lesions develop at the same time, appear identical, and are more prominent on the face and extremities. The pustules are round, firm, and deeply embedded in the skin. After 8 to 9 days, the pustules form a crust, and later, the scab separates from the skin, leaving a pitted scar. In fatal cases, death results from encephalitis, extensive bleeding, or secondary infection.

- Syringoma. With syringoma, adenoma of the sweat glands produces a yellowish or erythematous papular rash on the face (especially the eyelids), neck, and upper chest.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). SLE is characterized by a “butterfly rash” of erythematous maculopapules or discoid plaques that appear in a malar distribution across the nose and cheeks. Similar rashes may appear elsewhere, especially on exposed body areas. Other cardinal features include photosensitivity and nondeforming arthritis, especially in the hands, feet, and large joints. Common effects are patchy alopecia, mucous membrane ulceration, a low-grade or spiking fever, chills, lymphadenopathy, anorexia, weight loss, abdominal pain, diarrhea or constipation, dyspnea, tachycardia, hematuria, a headache, and irritability.

- Typhus. Typhus is a rickettsial disease transmitted to humans by fleas, mites, or body lice. Initial symptoms include a headache, myalgia, arthralgia, and malaise, followed by an abrupt onset of chills, a fever, nausea, and vomiting. A maculopapular rash may be present in some cases.

Recognizing Common Skin Lesions

MACULE

A small (usually less than 1 cm in diameter), flat blemish or discoloration that can be brown, tan, red, or white and has same texture as surrounding skin.

BULLA

A raised, thin-walled blister greater than 0.5 cm in diameter, containing clear or serous fluid.

VESICLE

A small (less than 0.5 cm in diameter), thin-walled, raised blister containing clear, serous, purulent, or bloody fluid.

PUSTULE

A circumscribed, pus- or lymph-filled, elevated lesion that varies in diameter and may be firm or soft and white or yellow.

WHEAL

A slightly raised, firm lesion of variable size and shape, surrounded by edema; skin may be red or pale.

NODULE

A small, firm, circumscribed, elevated lesion 1 to 2 cm in diameter with possible skin discoloration.

PAPULE

A small, solid, raised lesion less than 1 cm in diameter, with red to purple skin discoloration.

TUMOR

A solid, raised mass usually larger than 2 cm in diameter with possible skin discoloration.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Transient maculopapular rashes, usually on the trunk, may accompany reactions to many drugs, including antibiotics, such as tetracycline, ampicillin, cephalosporins, and sulfonamides; benzodiazepines, such as diazepam; lithium; phenylbutazone; gold salts; allopurinol; isoniazid; and salicylates.

Special Considerations

Apply cool compresses or an antipruritic lotion. Administer an antihistamine for allergic reactions and an antibiotic for infection.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient appropriate skin care measures, and explain ways to reduce itching.

Pediatric Pointers

Common causes of papular rashes in children are infectious diseases, such as molluscum contagiosum and scarlet fever; scabies; insect bites; allergies and drug reactions; and miliaria, which occurs in three forms, depending on the depth of sweat gland involvement.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients who are bedridden, the first sign of pressure ulcers is commonly an erythematous area, sometimes with firm papules. If not properly managed, these lesions progress to deep ulcers and can lead to death.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Wolff, K., & Johnson, R. A. (2009). Fitzpatrick’s color atlas & synopsis of clinical dermatology (6th ed.). New York, NY: McGraw Hill Medical.

Paralysis

Paralysis, the total loss of voluntary motor function, results from severe cortical or pyramidal tract damage. It can occur with a cerebrovascular disorder, degenerative neuromuscular disease, trauma, tumor, or central nervous system infection. Acute paralysis may be an early indicator of a life-threatening disorder such as Guillain-Barré syndrome.

Paralysis can be local or widespread, symmetrical or asymmetrical, transient or permanent, and spastic or flaccid. It’s commonly classified according to location and severity as paraplegia (sometimes, transient paralysis of the legs), quadriplegia (permanent paralysis of the arms, legs, and body below the level of the spinal lesion), or hemiplegia (unilateral paralysis of varying severity and permanence). Incomplete paralysis with profound weakness (paresis) may precede total paralysis in some patients.

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If paralysis has developed suddenly, suspect trauma or an acute vascular insult. After ensuring that the patient’s spine is properly immobilized, quickly determine his level of consciousness (LOC) and take his vital signs. Elevated systolic blood pressure, widening pulse pressure, and bradycardia may signal increasing intracranial pressure (ICP). If possible, elevate the patient’s head 30 degrees to decrease ICP, and attempt to keep his head straight and facing forward.

Evaluate the patient’s respiratory status, and be prepared to administer oxygen, insert an artificial airway, or provide intubation and mechanical ventilation, as needed. To help determine the nature of the patient’s injury, ask him for an account of the precipitating events. If he can’t respond, try to find an eyewitness.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient is in no immediate danger, perform a complete neurologic assessment. Start with the history, relying on family members for information if necessary. Ask about the onset, duration, intensity, and progression of paralysis and about the events preceding its development. Focus medical history questions on the incidence of degenerative neurologic or neuromuscular disease, recent infectious illness, sexually transmitted disease, cancer, or recent injury. Explore related signs and symptoms, noting fevers, headaches, vision disturbances, dysphagia, nausea and vomiting, bowel or bladder dysfunction, muscle pain or weakness, and fatigue.

Next, perform a complete neurologic examination, testing cranial nerve (CN), motor, and sensory function and deep tendon reflexes (DTRs). Assess strength in all major muscle groups, and note muscle atrophy. (See Testing Muscle Strength, pages 488 and 489.) Document all findings to serve as a baseline.

Medical Causes

- Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). ALS is an invariably fatal disorder that produces spastic or flaccid paralysis in the body’s major muscle groups, eventually progressing to total paralysis. Earlier findings include progressive muscle weakness, fasciculations, and muscle atrophy, usually beginning in the arms and hands. Cramping and hyperreflexia are also common. Involvement of respiratory muscles and the brain stem produces dyspnea and possibly respiratory distress. Progressive cranial nerve paralysis causes dysarthria, dysphagial drooling, choking, and difficulty chewing.

- Bell’s palsy. Bell’s palsy, a disease of CN VII, causes transient, unilateral facial muscle paralysis. The affected muscles sag, and eyelid closure is impossible. Other signs include increased tearing, drooling, and a diminished or absent corneal reflex.

- Botulism. Botulism is a bacterial toxin infection that can cause rapidly descending muscle weakness that progresses to paralysis within 2 to 4 days after the ingestion of contaminated food. Respiratory muscle paralysis leads to dyspnea and respiratory arrest. Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, blurred or double vision, bilateral mydriasis, dysarthria, and dysphagia are some early findings.

- Brain abscess. Advanced abscess in the frontal or temporal lobe can cause hemiplegia accompanied by other late findings, such as ocular disturbances, unequal pupils, a decreased LOC, ataxia, tremors, and signs of infection.

- Brain tumor. A tumor affecting the motor cortex of the frontal lobe may cause contralateral hemiparesis that progresses to hemiplegia. The onset is gradual, but paralysis is permanent without treatment. In early stages, a frontal headache and behavioral changes may be the only indicators. Eventually, seizures, aphasia, and signs of increased ICP (a decreased LOC and vomiting) develop.

- Conversion disorder. Hysterical paralysis, a classic symptom of conversion disorder, is characterized by the loss of voluntary movement with no obvious physical cause. It can affect any muscle group, appears and disappears unpredictably, and may occur with histrionic behavior (manipulative, dramatic, vain, irrational) or a strange indifference.

- Encephalitis. Variable paralysis develops in the late stages of encephalitis. Earlier signs and symptoms include a rapidly decreasing LOC (possibly coma), a fever, a headache, photophobia, vomiting, signs of meningeal irritation (nuchal rigidity, positive Kernig’s and Brudzinski’s signs), aphasia, ataxia, nystagmus, ocular palsies, myoclonus, and seizures.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome. Guillain-Barré syndrome is characterized by a rapidly developing, but reversible, ascending paralysis. It commonly begins as leg muscle weakness and progresses symmetrically, sometimes affecting even the cranial nerves, producing dysphagia, nasal speech, and dysarthria. Respiratory muscle paralysis may be life threatening. Other effects include transient paresthesia, orthostatic hypotension, tachycardia, diaphoresis, and bowel and bladder incontinence.

- Head trauma. Cerebral injury can cause paralysis due to cerebral edema and increased ICP. The onset is usually sudden. The location and extent vary, depending on the injury. Associated findings also vary, but include a decreased LOC; sensory disturbances, such as paresthesia and loss of sensation; a headache; blurred or double vision; nausea and vomiting; and focal neurologic disturbances.

- Multiple sclerosis (MS). With MS, paralysis commonly waxes and wanes until the later stages, when it may become permanent. Its extent can range from monoplegia to quadriplegia. In most patients, vision and sensory disturbances (paresthesia) are the earliest symptoms. Later findings are widely variable and may include muscle weakness and spasticity, nystagmus, hyperreflexia, an intention tremor, gait ataxia, dysphagia, dysarthria, impotence, and constipation. Urinary frequency, urgency, and incontinence may also occur.

- Myasthenia gravis. With myasthenia gravis, profound muscle weakness and abnormal fatigability may produce paralysis of certain muscle groups. Paralysis is usually transient in early stages, but becomes more persistent as the disease progresses. Associated findings depend on the areas of neuromuscular involvement; they include weak eye closure, ptosis, diplopia, lack of facial mobility, dysphagia, nasal speech, and frequent nasal regurgitation of fluids. Neck muscle weakness may cause the patient’s jaw to drop and his head to bob. Respiratory muscle involvement can lead to respiratory distress — dyspnea, shallow respirations, and cyanosis.

- Parkinson’s disease. Tremors, bradykinesia, and lead-pipe or cogwheel rigidity are the classic signs of Parkinson’s disease. Extreme rigidity can progress to paralysis, particularly in the extremities. In most cases, paralysis resolves with prompt treatment of the disease.

- Peripheral neuropathy. Typically, peripheral neuropathy produces muscle weakness that may lead to flaccid paralysis and atrophy. Related effects include paresthesia, a loss of vibration sensation, hypoactive or absent DTRs, neuralgia, and skin changes such as anhidrosis.

- Rabies. Rabies is an acute disorder that produces progressive flaccid paralysis, vascular collapse, coma, and death within 2 weeks of contact with an infected animal. Prodromal signs and symptoms — a fever; a headache; hyperesthesia; paresthesia, coldness, and itching at the bite site; photophobia; tachycardia; shallow respirations; and excessive salivation, lacrimation, and perspiration — develop almost immediately. Within 2 to 10 days, a phase of excitement begins, marked by agitation, cranial nerve dysfunction (pupil changes, hoarseness, facial weakness, ocular palsies), tachycardia or bradycardia, cyclic respirations, a high fever, urine retention, drooling, and hydrophobia.

- Seizure disorders. Seizures, particularly focal seizures, can cause transient local paralysis (Todd’s paralysis). Any part of the body may be affected, although paralysis tends to occur contralateral to the side of the irritable focus.

- Spinal cord injury. Complete spinal cord transection results in permanent spastic paralysis below the level of injury. Reflexes may return after spinal shock resolves. Partial transection causes variable paralysis and paresthesia, depending on the location and extent of injury. (See Understanding Spinal Cord Syndromes.)

- Spinal cord tumors. Paresis, pain, paresthesia, and variable sensory loss may occur along the nerve distribution pathway served by the affected cord segment. Eventually, these symptoms may progress to spastic paralysis with hyperactive DTRs (unless the tumor is in the cauda equina, which produces hyporeflexia) and, perhaps, bladder and bowel incontinence. Paralysis is permanent without treatment.

- Stroke. A stroke involving the motor cortex can produce contralateral paresis or paralysis. The onset may be sudden or gradual, and paralysis may be transient or permanent. Associated signs and symptoms vary widely and may include a headache, vomiting, seizures, a decreased LOC and mental acuity, dysarthria, dysphagia, ataxia, contralateral paresthesia or sensory loss, apraxia, agnosia, aphasia, vision disturbances, emotional lability, and bowel and bladder dysfunction.

- Subarachnoid hemorrhage. Subarachnoid hemorrhage is a potentially life-threatening disorder that can produce sudden paralysis. The condition may be temporary, resolving with decreasing edema, or permanent, if tissue destruction has occurred. Other acute effects are a severe headache, mydriasis, photophobia, aphasia, a sharply decreased LOC, nuchal rigidity, vomiting, and seizures.

- Syringomyelia. Syringomyelia is a degenerative spinal cord disease that produces segmental paresis, leading to flaccid paralysis of the hands and arms. Reflexes are absent, and loss of pain and temperature sensation is distributed over the neck, shoulders, and arms in a capelike pattern.

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA). Episodic TIAs may cause transient unilateral paresis or paralysis accompanied by paresthesia, blurred or double vision, dizziness, aphasia, dysarthria, a decreased LOC, and other site-dependent effects.

- West Nile encephalitis. West Nile encephalitis is a brain infection that’s caused by West Nile virus, a mosquito-borne Flavivirus endemic to Africa, the Middle East, western Asia, and the United States. Mild infections are common and include a fever, a headache, and body aches, which are sometimes accompanied by a skin rash and swollen lymph glands. More severe infections are marked by a headache, a high fever, neck stiffness, stupor, disorientation, coma, tremors, occasional seizures, paralysis and, rarely, death.

Other Causes

- Drugs. The therapeutic use of neuromuscular blockers, such as pancuronium or curare, produces paralysis.

- Electroconvulsive therapy (ECT). ECT can produce acute, but transient, paralysis.

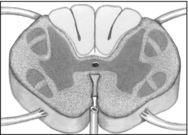

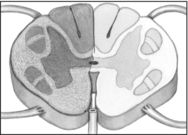

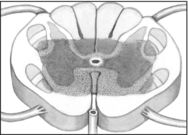

Understanding Spinal Cord Syndromes

When a patient’s spinal cord is incompletely severed, he experiences partial motor and sensory loss. Most incomplete cord lesions fit into one of the syndromes described below.

Anterior cord syndrome, usually resulting from a flexion injury, causes motor paralysis and loss of pain and temperature sensation below the level of injury. Touch, proprioception, and vibration sensation are usually preserved.

Brown-Séquard syndrome can result from flexion, rotation, or penetration injury. It’s characterized by unilateral motor paralysis ipsilateral to the injury and a loss of pain and temperature sensation contralateral to the injury.

Central cord syndrome is caused by hyperextension or flexion injury. Motor loss is variable and greater in the arms than in the legs; sensory loss is usually slight.

Posterior cord syndrome, produced by a cervical hyperextension injury, causes only a loss of proprioception and light touch sensation. Motor function remains intact.

Special Considerations

Because a paralyzed patient is particularly susceptible to complications of prolonged immobility, provide frequent position changes, meticulous skin care, and frequent chest physiotherapy. He may benefit from passive range-of-motion exercises to maintain muscle tone, the application of splints to prevent contractures, and the use of footboards or other devices to prevent footdrop. If his cranial nerves are affected, the patient will have difficulty chewing and swallowing. Provide a thickened liquid or soft diet, and keep suction equipment on hand in case aspiration occurs. Feeding tubes or total parenteral nutrition may be necessary with severe paralysis. Paralysis and accompanying vision disturbances may make ambulation hazardous; provide a call light, and show the patient how to call for help. As appropriate, arrange for physical, speech, swallowing, or occupational therapy.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying cause of the paralysis; provide referrals to social and psychological services. Teach the patient and family how to provide care at home, including passive range-of-motion exercises, frequent turning, and chest physiotherapy.

Pediatric Pointers

Although children may develop paralysis from an obvious cause — such as trauma, infection, or a tumor — they may also develop it from a hereditary or congenital disorder, such as Tay-Sachs disease, Werdnig-Hoffmann disease, spina bifida, or cerebral palsy.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sarwark, J. F. (2010). Essentials of musculoskeletal care. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Paresthesia

Paresthesia is an abnormal sensation or combination of sensations — commonly described as numbness, prickling, or tingling — felt along peripheral nerve pathways; these sensations generally aren’t painful. Unpleasant or painful sensations, on the other hand, are termed dysesthesias. Paresthesia may develop suddenly or gradually and may be transient or permanent.

A common symptom of many neurologic disorders, paresthesia may also result from a systemic disorder or particular drug. It may reflect damage or irritation of the parietal lobe, thalamus, spinothalamic tract, or spinal or peripheral nerves — the neural circuit that transmits and interprets sensory stimuli.

History and Physical Examination

First, explore the paresthesia. When did abnormal sensations begin? Have the patient describe their character and distribution. Also, ask about associated signs and symptoms, such as sensory loss and paresis or paralysis. Next, take a medical history, including neurologic, cardiovascular, metabolic, renal, and chronic inflammatory disorders, such as arthritis or lupus. Has the patient recently sustained a traumatic injury or had surgery or an invasive procedure that may have damaged peripheral nerves?

Focus the physical examination on the patient’s neurologic status. Assess his level of consciousness (LOC) and cranial nerve function. Test muscle strength and deep tendon reflexes (DTRs) in limbs affected by paresthesia. Systematically evaluate light touch, pain, temperature, vibration, and position sensation. (See Testing for Analgesia, pages 42 and 43.) Also, note skin color and temperature, and palpate pulses.

Medical Causes

- Arterial occlusion (acute). With acute arterial occlusion, sudden paresthesia and coldness may develop in one or both legs with a saddle embolus. Paresis, intermittent claudication, and aching pain at rest are also characteristic. The extremity becomes mottled with a line of temperature and color demarcation at the level of occlusion. Pulses are absent below the occlusion, and the capillary refill time is increased.

- Arteriosclerosis obliterans. Arteriosclerosis obliterans produces paresthesia, intermittent claudication (most common symptom), diminished or absent popliteal and pedal pulses, pallor, paresis, and coldness in the affected leg.

- Arthritis. Rheumatoid or osteoarthritic changes in the cervical spine may cause paresthesia in the neck, shoulders, and arms. The lumbar spine occasionally is affected, causing paresthesia in one or both legs and feet.

- Brain tumor. Tumors affecting the sensory cortex in the parietal lobe may cause progressive contralateral paresthesia accompanied by agnosia, apraxia, agraphia, homonymous hemianopsia, and a loss of proprioception.

- Buerger’s disease. With Buerger’s disease, a smoking-related inflammatory occlusive disorder, exposure to cold makes the feet cold, cyanotic, and numb; later, they redden, become hot, and tingle. Intermittent claudication, which is aggravated by exercise and relieved by rest, is also common. Other findings include weak peripheral pulses, migratory superficial thrombophlebitis and, later, ulceration, muscle atrophy, and gangrene.

- Diabetes mellitus. Diabetic neuropathy can cause paresthesia with a burning sensation in the hands and legs. Other findings include insidious, permanent anosmia, fatigue, polyuria, polydipsia, weight loss, and polyphagia.

- Guillain-Barré syndrome. With Guillain-Barré syndrome, transient paresthesia may precede muscle weakness, which usually begins in the legs and ascends to the arms and facial nerves. Weakness may progress to total paralysis. Other findings include dysarthria, dysphagia, nasal speech, orthostatic hypotension, bladder and bowel incontinence, diaphoresis, tachycardia and, possibly, signs of life-threatening respiratory muscle paralysis.

- Head trauma. Unilateral or bilateral paresthesia may occur when head trauma causes a concussion or contusion; however, sensory loss is more common. Other findings include variable paresis or paralysis, a decreased LOC, a headache, blurred or double vision, nausea and vomiting, dizziness, and seizures.

- Herniated disk. Herniation of a lumbar or cervical disk may cause an acute or a gradual onset of paresthesia along the distribution pathways of affected spinal nerves. Other neuromuscular effects include severe pain, muscle spasms, and weakness that may progress to atrophy unless herniation is relieved.

- Herpes zoster. An early symptom of herpes zoster, paresthesia occurs in the dermatome supplied by the affected spinal nerve. Within several days, this dermatome is marked by a pruritic, erythematous, vesicular rash associated with sharp, shooting, or burning pain.

- Hyperventilation syndrome. Usually triggered by acute anxiety, hyperventilation syndrome may produce transient paresthesia in the hands, feet, and perioral area, accompanied by agitation, vertigo, syncope, pallor, muscle twitching and weakness, carpopedal spasm, and cardiac arrhythmias.

- Migraine headache. Paresthesia in the hands, face, and perioral area may herald an impending migraine headache. Other prodromal symptoms include scotomas, hemiparesis, confusion, dizziness, and photophobia. These effects may persist during the characteristic throbbing headache and continue after it subsides.

- Multiple sclerosis (MS). With MS, demyelination of the sensory cortex or spinothalamic tract may produce paresthesia — typically one of the earliest symptoms. Like other effects of MS, paresthesia commonly waxes and wanes until the later stages, when it may become permanent. Associated findings include muscle weakness, spasticity, and hyperreflexia.

- Peripheral nerve trauma. Injury to a major peripheral nerve can cause paresthesia — commonly dysesthesia — in the area supplied by that nerve. Paresthesia begins shortly after trauma and may be permanent. Other findings are flaccid paralysis or paresis, hyporeflexia, and variable sensory loss.

- Peripheral neuropathy. Peripheral neuropathy can cause progressive paresthesia in all extremities. The patient also commonly displays muscle weakness, which may lead to flaccid paralysis and atrophy, a loss of vibration sensation, diminished or absent DTRs, neuralgia, and cutaneous changes, such as glossy, red skin and anhidrosis.

- Rabies. Paresthesia, coldness, and itching at the site of an animal bite herald the prodromal stage of rabies. Other prodromal signs and symptoms are a fever, a headache, photophobia, hyperesthesia, tachycardia, shallow respirations, and excessive salivation, lacrimation, and perspiration.

- Raynaud’s disease. Exposure to cold or stress makes the fingers turn pale, cold, and cyanotic; with rewarming, they become red and paresthetic. Ulceration may occur in chronic cases.

- Seizure disorders. Seizures originating in the parietal lobe usually cause paresthesia of the lips, fingers, and toes. The paresthesia may act as auras that precede tonic-clonic seizures.

- Spinal cord injury. Paresthesia may occur in partial spinal cord transection, after spinal shock resolves. It may be unilateral or bilateral, occurring at or below the level of the lesion. Associated sensory and motor loss is variable. (See Understanding Spinal Cord Syndromes, page 555.) Spinal cord disorders may be associated with paresthesia on head flexion (Lhermitte’s sign).

- Spinal cord tumors. Paresthesia, paresis, pain, and sensory loss along nerve pathways served by the affected cord segment result from such tumors. Eventually, paresis may cause spastic paralysis with hyperactive DTRs (unless the tumor is in the cauda equina, which produces hyporeflexia) and, possibly, bladder and bowel incontinence.

- Stroke. Although contralateral paresthesia may occur with stroke, sensory loss is more common. Associated features vary with the artery affected and may include contralateral hemiplegia, a decreased LOC, and homonymous hemianopsia.

- Systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE). SLE may cause paresthesia, but its primary signs and symptoms include nondeforming arthritis (usually of the hands, feet, and large joints), photosensitivity, and a “butterfly rash” that appears across the nose and cheeks.

- Tabes dorsalis. With tabes dorsalis, paresthesia — especially of the legs — is a common, but late, symptom. Other findings include ataxia, loss of proprioception and pain and temperature sensation, absent DTRs, Charcot’s joints, Argyll Robertson pupils, incontinence, and impotence.

- Transient ischemic attack (TIA). Paresthesia typically occurs abruptly with a TIA and is limited to one arm or another isolated part of the body. It usually lasts about 10 minutes and is accompanied by paralysis or paresis. Associated findings include a decreased LOC, dizziness, unilateral vision loss, nystagmus, aphasia, dysarthria, tinnitus, facial weakness, dysphagia, and an ataxic gait.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Phenytoin, chemotherapeutic agents (such as vincristine, vinblastine, and procarbazine), isoniazid, nitrofurantoin, chloroquine, and parenteral gold therapy may produce transient paresthesia that disappears when the drug is discontinued.

- Radiation therapy. Long-term radiation therapy may eventually cause peripheral nerve damage, resulting in paresthesia.

Special Considerations

Because paresthesia is commonly accompanied by patchy sensory loss, teach the patient safety measures. For example, have him test bathwater with a thermometer.

Patient Counseling

Discuss safety measures, and tell the patient which signs and symptoms to report.

Pediatric Pointers

Although children may experience paresthesia associated with the same causes as adults, many can’t describe this symptom. Nevertheless, hereditary polyneuropathies are usually first recognized in childhood.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sarwark, J. F. (2010). Essentials of musculoskeletal care. Rosemont, IL: American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Paroxysmal Nocturnal Dyspnea

Typically dramatic and terrifying to the patient, this sign refers to an attack of dyspnea that abruptly awakens the patient. Common findings include diaphoresis, coughing, wheezing, and chest discomfort. The attack abates after the patient sits up or stands for several minutes, but may recur every 2 to 3 hours.

Paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea is a sign of left-sided heart failure. It may result from decreased respiratory drive, impaired left ventricular function, enhanced reabsorption of interstitial fluid, or increased thoracic blood volume. All of these pathophysiologic mechanisms cause dyspnea to worsen when the patient lies down.

History and Physical Examination

Begin by exploring the patient’s complaint of dyspnea. Does he have dyspneic attacks only at night or at other times as well, such as after exertion or while sitting down? If so, what type of activity triggers the attack? Does he experience coughing, wheezing, fatigue, or weakness during an attack? Find out if he has a history of lower extremity edema or jugular vein distention. Ask if he sleeps with his head elevated and, if so, on how many pillows or if he sleeps in a reclining chair. Obtain a cardiopulmonary history. Does the patient or a family member have a history of a myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, or hypertension or of chronic bronchitis, emphysema, or asthma? Has the patient had cardiac surgery?

Next, perform a physical examination. Begin by taking the patient’s vital signs and forming an overall impression of his appearance. Is he noticeably cyanotic or edematous? Auscultate the lungs for crackles and wheezing and the heart for gallops and arrhythmias.

Medical Causes

- Left-sided heart failure. Dyspnea — on exertion, during sleep, and eventually even at rest — is an early sign of left-sided heart failure. This sign is characteristically accompanied by Cheyne-Stokes respirations, diaphoresis, weakness, wheezing, and a persistent, nonproductive cough or a cough that produces clear or blood-tinged sputum. As the patient’s condition worsens, he develops tachycardia, tachypnea, alternating pulse (commonly initiated by a premature beat), a ventricular gallop, crackles, and peripheral edema.

With advanced left-sided heart failure, the patient may also exhibit severe orthopnea, cyanosis, clubbing, hemoptysis, and cardiac arrhythmias as well as signs and symptoms of shock, such as hypotension, a weak pulse, and cold, clammy skin.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as a chest X-ray, echocardiography, exercise electrocardiography, and cardiac blood pool imaging. If the hospitalized patient experiences paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea, assist him to a sitting position or help him walk around the room. If necessary, provide supplemental oxygen. Try to calm him because anxiety can exacerbate dyspnea.

Patient Counseling

Explain signs and symptoms that require immediate medical attention, and discuss dietary and fluid restrictions. Explore positions that can ease breathing, and teach about prescribed medications.

Pediatric Pointers

In a child, paroxysmal nocturnal dyspnea usually stems from a congenital heart defect that precipitates heart failure. Help relieve the child’s dyspnea by elevating his head and calming him.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Peau d’orange

Usually a late sign of breast cancer, peau d’orange (orange peel skin) is the edematous thickening and pitting of breast skin. This slowly developing sign can also occur with breast or axillary lymph node infection, erysipelas, or Graves’ disease. Its striking orange peel appearance stems from lymphatic edema around deepened hair follicles. (See Recognizing peau d’orange, page 562.)

History and Physical Examination

Ask the patient when she first detected peau d’orange. Has she noticed lumps, pain, or other breast changes? Does she have related signs and symptoms, such as malaise, achiness, and weight loss? Is she lactating, or has she recently weaned her infant? Has she had previous axillary surgery that might have impaired lymphatic drainage of a breast?

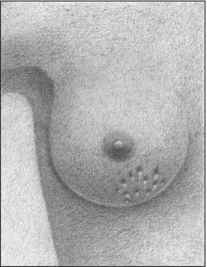

Recognizing Peau D’orange

In peau d’orange, the skin appears to be pitted (as shown below). This condition usually indicates late-stage breast cancer.

In a well-lit examining room, observe the patient’s breasts. Estimate the extent of the peau d’orange, and check for erythema. Assess the nipples for discharge, deviation, retraction, dimpling, and cracking. Gently palpate the area of peau d’orange, noting warmth or induration. Then, palpate the entire breast, noting fixed or mobile lumps, and the axillary lymph nodes, noting enlargement. Finally, take the patient’s temperature.

Medical Causes

- Breast abscess. Usually affecting lactating women with milk stasis, breast abscess causes peau d’orange, malaise, breast tenderness and erythema, and a sudden fever that may be accompanied by shaking chills. A cracked nipple may produce a purulent discharge, and an indurated or palpable soft mass may be present.

- Breast cancer. Advanced breast cancer is the most likely cause of peau d’orange, which usually begins in the dependent part of the breast or the areola. Palpation typically reveals a firm, immobile mass that adheres to the skin above the area of peau d’orange. Inspection of the breasts may reveal changes in contour, size, or symmetry. Inspection of the nipples may reveal deviation, erosion, retraction, and a thin and watery, bloody, or purulent discharge. The patient may report a burning and itching sensation in the nipples as well as a sensation of warmth or heat in the breast. Breast pain may occur, but it isn’t a reliable indicator of cancer.

Special Considerations

Because peau d’orange usually signals advanced breast cancer, provide emotional support for the patient. Encourage her to express her fears and concerns. Clearly explain expected diagnostic tests, such as mammography and breast biopsy.

Patient Counseling

Explain diagnostic tests the patient needs, and teach her how to do monthly breast self-examinations. Discuss signs and symptoms she needs to report.

REFERENCES

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Schuiling, K. D. (2013). Women’s gynecologic health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

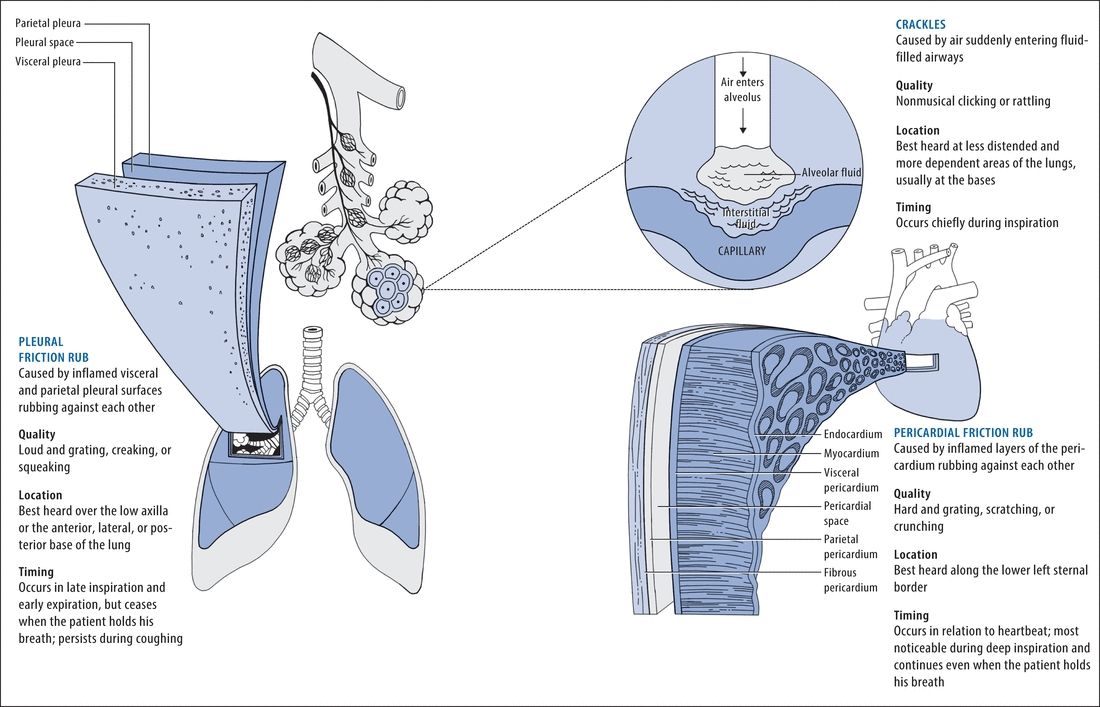

Pericardial Friction Rub

Commonly transient, a pericardial friction rub is a scratching, grating, or crunching sound that occurs when two inflamed layers of the pericardium slide over one another. Ranging from faint to loud, this abnormal sound is best heard along the lower left sternal border during deep inspiration. It indicates pericarditis, which can result from an acute infection, a cardiac or renal disorder, postpericardiotomy syndrome, or the use of certain drugs.

Occasionally, a pericardial friction rub can resemble a murmur (See Pericardial Friction Rub or Murmur?) or a pleural friction rub. However, the classic pericardial friction rub has three components. (See Understanding Pericardial Friction Rubs.)

History and Physical Examination

Obtain a complete medical history, noting especially cardiac dysfunction. Has the patient recently had a myocardial infarction or cardiac surgery? Has he ever had pericarditis or a rheumatic disorder, such as rheumatoid arthritis or systemic lupus erythematosus? Does he have chronic renal failure or an infection? If the patient complains of chest pain, ask him to describe its character and location. What relieves the pain? What worsens it?

Take the patient’s vital signs, noting especially hypotension, tachycardia, an irregular pulse, tachypnea, and a fever. Inspect for jugular vein distention, edema, ascites, and hepatomegaly. Auscultate the lungs for crackles. (See Comparing Auscultation Findings, pages 564 and 565.)

EXAMINATION TIP Pericardial Friction Rub or Murmur?

EXAMINATION TIP Pericardial Friction Rub or Murmur?

Is the sound you hear a pericardial friction rub or a murmur? Here’s how to tell. The classic pericardial friction rub has three sound components, which are related to the phases of the cardiac cycle. In some patients, however, the rub’s presystolic and early diastolic sounds may be inaudible, causing the rub to resemble the murmur of mitral insufficiency or aortic stenosis and insufficiency.

If you don’t detect the classic three-component sound, you can distinguish a pericardial friction rub from a murmur by auscultating again and asking yourself these questions:

HOW DEEP IS THE SOUND?

A pericardial friction rub usually sounds superficial; a murmur sounds deeper in the chest.

DOES THE SOUND RADIATE?

A pericardial friction rub usually doesn’t radiate; a murmur may radiate widely.

DOES THE SOUND VARY WITH INSPIRATION OR CHANGES IN PATIENT POSITION?

A pericardial friction rub is usually loudest during inspiration and is best heard when the patient leans forward. A murmur varies in timing and duration with both factors.

Medical Causes

- Pericarditis. A pericardial friction rub is the hallmark of acute pericarditis. This disorder also causes sharp precordial or retrosternal pain that usually radiates to the left shoulder, neck, and back. The pain worsens when the patient breathes deeply, coughs, or lies flat and, possibly, when he swallows. It abates when he sits up and leans forward. The patient may also develop a fever, dyspnea, tachycardia, and arrhythmias.

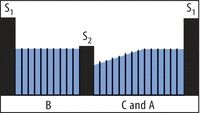

Comparing Auscultation Findings

During auscultation, you may detect a pleural friction rub, a pericardial friction rub, or crackles — three abnormal sounds that are commonly confused. Use these illustrations to help clarify auscultation findings.

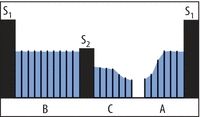

EXAMINATION TIP Understanding Pericardial Friction Rubs

EXAMINATION TIP Understanding Pericardial Friction Rubs

The complete, or classic, pericardial friction rub is triphasic. Its three sound components are linked to phases of the cardiac cycle. The presystolic component (A) reflects atrial systole and precedes the first heart sound (S1). The systolic component (B) — usually the loudest — reflects ventricular systole and occurs between the S1 and second heart sound (S2). The early diastolic component (C) reflects ventricular diastole and follows S2.

Sometimes, the early diastolic component merges with the presystolic component, producing a diphasic to-and-fro sound on auscultation. In other patients, auscultation may detect only one component — a monophasic rub, typically during ventricular systole.

TRIPHASIC RUB

DIPHASIC RUB

MONOPHASIC RUB

With chronic constrictive pericarditis, a pericardial friction rub develops gradually and is accompanied by signs of decreased cardiac filling and output, such as peripheral edema, ascites, jugular vein distention on inspiration (Kussmaul’s sign), and hepatomegaly. Dyspnea, orthopnea, paradoxical pulse, and chest pain may also occur.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Procainamide and chemotherapeutic drugs can cause pericarditis.

Special Considerations

Continue to monitor the patient’s cardiovascular status. If the pericardial friction rub disappears, be alert for signs of cardiac tamponade: pallor; cool, clammy skin; hypotension; tachycardia; tachypnea; paradoxical pulse; and increased jugular vein distention. If these signs occur, prepare the patient for pericardiocentesis to prevent cardiovascular collapse.

Ensure that the patient gets adequate rest. Give an anti-inflammatory, antiarrhythmic, diuretic, or antimicrobial to treat the underlying cause. If necessary, prepare him for a pericardiectomy to promote adequate cardiac filling and contraction.

Patient Counseling

Explain the underlying disorder, its treatments, and what the patient can do to minimize his symptoms.

Pediatric Pointers

Bacterial pericarditis may develop during the first two decades of life, usually before age 6. Although a pericardial friction rub may occur, other signs and symptoms — such as a fever, tachycardia, dyspnea, chest pain, jugular vein distention, and hepatomegaly — more reliably indicate this life-threatening disorder. A pericardial friction rub may also occur after surgery to correct congenital cardiac anomalies. However, it usually vanishes without the development of pericarditis.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Peristaltic Waves, Visible

With intestinal obstruction, peristalsis temporarily increases in strength and frequency as the intestine contracts to force its contents past the obstruction. As a result, visible peristaltic waves may roll across the abdomen. Typically, these waves appear suddenly and vanish quickly because increased peristalsis overcomes the obstruction or the GI tract becomes atonic. Peristaltic waves are best detected by stooping at the patient’s side and inspecting his abdominal contour while he’s in a supine position.

Visible peristaltic waves may also reflect normal stomach and intestinal contractions in thin patients or in malnourished patients with abdominal muscle atrophy.

History and Physical Examination

After observing peristaltic waves, collect pertinent history data. Ask about a history of a pyloric ulcer, stomach cancer, or chronic gastritis, which can lead to pyloric obstruction. Also, ask about conditions leading to intestinal obstruction, such as intestinal tumors or polyps, gallstones, chronic constipation, and a hernia. Has the patient had recent abdominal surgery? Make sure to obtain a drug history.

Determine if the patient has related symptoms. Spasmodic abdominal pain, for example, accompanies small-bowel obstruction, whereas colicky pain accompanies pyloric obstruction. Is the patient experiencing nausea and vomiting? If he has vomited, ask about the consistency, amount, and color of the vomitus. Lumpy vomitus may contain undigested food particles; green or brown vomitus may contain bile or fecal matter.

Next, with the patient in a supine position, inspect the abdomen for distention, surgical scars and adhesions, or visible loops of bowel. Auscultate for bowel sounds, noting high-pitched, tinkling sounds. Then, jar the patient’s bed (or roll the patient from side to side) and auscultate for a succussion splash — a splashing sound in the stomach from retained secretions due to pyloric obstruction. Palpate the abdomen for rigidity and tenderness, and percuss for tympany. Check the skin and mucous membranes for dryness and poor skin turgor, indicating dehydration. Take the patient’s vital signs, noting especially tachycardia and hypotension, which indicate hypovolemia.

Medical Causes

- Large-bowel obstruction. Visible peristaltic waves in the upper abdomen are an early sign of large-bowel obstruction. Obstipation, however, may be the earliest finding. Other characteristic signs and symptoms develop more slowly than in small-bowel obstruction. These include nausea, colicky abdominal pain (milder than in small-bowel obstruction), gradual and eventually marked abdominal distention, and hyperactive bowel sounds.

- Pyloric obstruction. Peristaltic waves may be detected in a swollen epigastrium or in the left upper quadrant, usually beginning near the left rib margin and rolling from left to right. Related findings include vague epigastric discomfort or colicky pain after eating, nausea, vomiting, anorexia, and weight loss. Auscultation reveals a loud succussion splash.

- Small-bowel obstruction. Early signs of mechanical obstruction of the small bowel include peristaltic waves rolling across the upper abdomen and intermittent, cramping periumbilical pain. Associated signs and symptoms include nausea, vomiting of bilious or, later, fecal material, and constipation; in partial obstruction, diarrhea may occur. Hyperactive bowel sounds and slight abdominal distention also occur early.

Special Considerations

Because visible peristaltic waves are an early sign of intestinal obstruction, monitor the patient’s status and prepare him for diagnostic evaluation and treatment. Withhold food and fluids, and explain the purpose and procedure of abdominal X-rays and barium studies, which can confirm obstruction.

If tests confirm obstruction, nasogastric suctioning may be performed to decompress the stomach and small bowel. Provide frequent oral hygiene, and watch for a thick, swollen tongue and dry mucous membranes, indicating dehydration. Frequently monitor the patient’s vital signs and intake and output.

Patient Counseling

Discuss dietary and fluid requirements. Encourage the use of stool softeners and increased intake of high-fiber foods for patients with chronic constipation.

Pediatric Pointers

In infants, visible peristaltic waves may indicate pyloric stenosis. In small children, peristaltic waves may be visible normally because of the protuberant abdomen, or visible waves may indicate bowel obstruction stemming from congenital anomalies, volvulus, or swallowing a foreign body.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients who present with visible peristaltic waves, always check for fecal impaction, which is a common problem among those of this age group. Also, obtain a detailed drug history; antidepressants and antipsychotics can predispose patients to constipation and bowel obstruction.

REFERENCES

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

McCance, K. L., Huether, S. E., Brashers, V. L., & Rote, N. S. (2010). Pathophysiology: The biologic basis for disease in adults and children. Maryland Heights, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012). Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Photophobia

A common symptom, photophobia is an abnormal sensitivity to light. In many patients, photophobia simply indicates increased eye sensitivity without underlying pathology. For example, it can stem from wearing contact lenses excessively or using poorly fitted lenses. However, in others, this symptom can result from a systemic disorder, an ocular disorder or trauma, or the use of certain drugs. (See Photophobia: Common Causes and Associated Findings.)

History and Physical Examination

If the patient reports photophobia, find out when it began and how severe it is. Did it follow eye trauma, a chemical splash, or exposure to the rays of a sun lamp? If photophobia results from trauma, avoid manipulating the eyes. Ask the patient about eye pain and have him describe its location, duration, and intensity. Does he have a sensation of a foreign body in his eye? Does he have other signs and symptoms, such as increased tearing and vision changes?

Next, take the patient’s vital signs, and assess his neurologic status. Assess visual activity, unless the cause is a chemical burn. Follow this with a careful eye examination, inspecting the eyes’ external structures for abnormalities. Examine the conjunctiva and sclera, noting their color. Characterize the amount and consistency of any discharge. Then, check pupillary reaction to light. Evaluate extraocular muscle function by testing the six cardinal fields of gaze, and test visual acuity in both eyes.

During your assessment, keep in mind that although photophobia can accompany life-threatening meningitis, it isn’t a cardinal sign of meningeal irritation.

Medical Causes

- Burns. With a chemical burn, photophobia and eye pain may be accompanied by erythema and blistering on the face and lids, miosis, diffuse conjunctival injection, and corneal changes. The patient experiences blurred vision and may be unable to keep his eyes open. With an ultraviolet radiation burn, photophobia occurs with moderate to severe eye pain. These symptoms develop about 12 hours after exposure to the rays of a welding arc or sun lamp.

- Conjunctivitis. Moderate to severe conjunctivitis can cause photophobia. Other common findings of conjunctivitis include conjunctival injection, increased tearing, a foreign body sensation, a feeling of fullness around the eyes, and eye pain, burning, and itching. Allergic conjunctivitis is distinguished by a stringy white eye discharge and milky red injection. Bacterial conjunctivitis tends to cause a copious, mucopurulent, flaky eye discharge that may make the eyelids stick together as well as brilliant red conjunctiva. Fungal conjunctivitis produces a thick, purulent discharge, extreme redness, and crusting, sticky eyelids. Viral conjunctivitis causes copious tearing with little discharge as well as enlargement of the preauricular lymph nodes.

- Corneal abrasion. A common finding with corneal abrasion, photophobia is usually accompanied by excessive tearing, conjunctival injection, visible corneal damage, and a foreign body sensation in the eye. Blurred vision and eye pain may also occur.

- Corneal ulcer. A corneal ulcer is a vision-threatening disorder that causes severe photophobia and eye pain aggravated by blinking. Impaired visual acuity may accompany blurring, eye discharge, and sticky eyelids. Conjunctival injection may occur even though an area of the cornea may appear white and opaque. A bacterial ulcer may be irregularly shaped. A fungal ulcer may be surrounded by progressively clearer rings.

- Iritis (acute). Severe photophobia may result from acute iritis, along with marked conjunctival injection, moderate to severe eye pain, and blurred vision. The pupil may be constricted and may respond poorly to light.

- Keratitis (interstitial). Keratitis is a corneal inflammation that causes photophobia, eye pain, blurred vision, dramatic conjunctival injection, and cloudy corneas.

- Meningitis (acute bacterial). A common symptom of meningitis, photophobia may occur with other signs of meningeal irritation, such as nuchal rigidity, hyperreflexia, and opisthotonos. Brudzinski’s and Kernig’s signs can be elicited. A fever, an early finding, may be accompanied by chills. Related signs and symptoms may include a headache, vomiting, ocular palsies, facial weakness, pupillary abnormalities, and hearing loss. With severe meningitis, seizures may occur along with stupor progressing to coma.

- Migraine headache. Photophobia and noise sensitivity are prominent features of a common migraine. Typically severe, this aching or throbbing headache may also cause fatigue, blurred vision, nausea, and vomiting.

- Uveitis. Anterior and posterior uveitis can cause photophobia. Typically, anterior uveitis also produces moderate to severe eye pain, severe conjunctival injection, and a small, nonreactive pupil. Posterior uveitis develops slowly, causing visual floaters, eye pain, pupil distortion, conjunctival injection, and blurred vision.

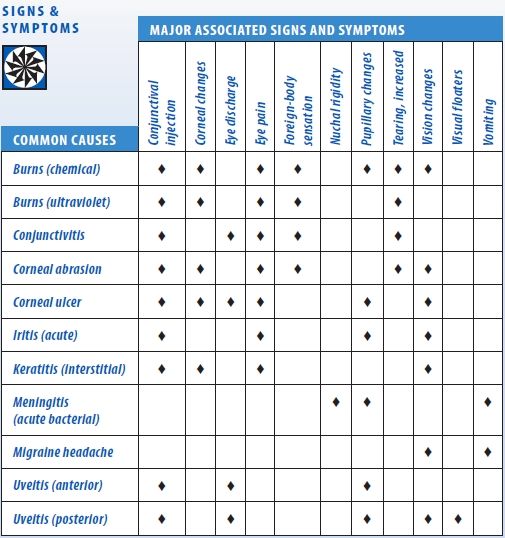

Photophobia: Common Causes and Associated Findings

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree