Jan Odom-Forren

Postoperative Patient Care and Pain Management

The postoperative phase of care begins as soon as the surgical procedure concludes and the patient is transferred to the postanesthesia care unit (PACU). The PACU, in the past, was called the recovery room or postanesthesia room. Florence Nightingale (1863) first described a postanesthesia area this way: “It is not uncommon, in small country hospitals, to have a recess or small room leading from the operating theater in which the patients remain until they have recovered, or at least recovered from the immediate effects of the operation.”

An assigned area for the care of the postoperative patient is a relatively recent addition to surgical patient care. Although surgical procedures have been performed for thousands of years, and general anesthesia has been available for almost 150 years, PACUs became common only in the second half of the 20th century. A few recovery rooms were opened in the 1920s and 1930s. In the 1940s numerous PACUs opened because of the shortage of nurses during the war years and the need to centralize patients, equipment, and personnel for postoperative care. Hospitals soon realized that use of the PACU decreased patient morbidity and mortality and shortened the stays of some patients. When researchers reported that as many as a third of perioperative deaths examined over an 11-year period could have been prevented by improved postoperative nursing care (Odom-Forren and Clifford, 2010; Ruth et al, 1947), many hospitals opened PACUs.

PACUs have since flourished. Technologic innovation has profoundly affected PACUs, as in other critical care areas. The complexity of anesthesia management demands specially trained nurses who have expertise in prompt recognition and management of postoperative complications. Most patients who receive general anesthesia, major regional anesthesia, or monitored anesthesia care are transferred to the PACU. PACU is considered postanesthesia phase I, in which basic life-sustaining needs are of the highest priority. Patients then transition to phase II (preparation for discharge home), an inpatient setting, or a critical care unit (CCU, or intensive care unit [ICU]) (ASPAN, 2012). In some PACUs, because of space constraints and cost containment, PACU nurses also manage the care of overflow ICU or telemetry patients or provide space for managing pain or inserting central lines, for example.

PACUs are adjacent to the surgical suite with easy access for patient transport. The patient’s status is assessed for needs during transfer (e.g., oxygen, manual positive-pressure ventilation device, a patient hospital bed). A perioperative nurse accompanies the patient to the PACU with an anesthesia provider and gives a hand-off report on the status of the patient to a perianesthesia nurse. A PACU nurse assumes care of the patient after initial assessment of the patient and report from the transferring team.

Perianesthesia Considerations

Assessment

Admission to the PACU.

Initial assessment of the postoperative patient begins with an immediate determination of airway and circulatory adequacy. The airway is assessed for patency, humidified oxygen applied, and respirations counted. Pulse oximetry is initiated on all patients, and the quality of breath sounds determined. The PACU nurse connects the patient to the cardiac monitor, and evaluates rate and rhythm. Blood pressure is measured by means of a manual cuff or an automatic cuff. If the patient has an arterial line, the PACU nurse connects it to the monitor.

After the PACU nurse assesses the ABCs (airway, breathing, circulation), the perioperative nurse and anesthesia provider give a comprehensive hand-off report. A patient hand-off is defined by the Joint Commission Center for Transforming Healthcare (2010) as a transfer and acceptance of patient care responsibility achieved through effective communication. It is a real-time process of passing patient-specific information from one caregiver to another or from one team of caregivers to another for the purpose of ensuring continuity and safety. Standardization of how information is communicated ensures that the information will be accurate and complete. The perioperative nurse collaborates by adding and verifying important patient information. Box 10-1 includes suggestions on what each surgical team member reports.

The patient’s American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical classification status (see Chapter 5) also is provided during the hand-off report. Useful information that the perioperative nurse also provides includes airway status and presence of tubes, drains, catheters, and intravascular lines. Any postoperative orders to be initiated in the PACU are discussed at this time.

The anesthesia provider should not leave the patient until the PACU nurse accepts responsibility for the patient’s care. Standard III-3 of the ASA’s Standards for Postanesthesia Care (ASA, 2009) states that “the member of the anesthesia care team shall remain in the PACU until the PACU nurse accepts responsibility for the nursing care of the patient.”

Initial Assessment.

After immediate assessment of the ABCs and completion of the hand-off report, the PACU nurse begins a more thorough postanesthesia assessment. The assessment is performed quickly and is specific, in part, to the type of operative procedure. Recommended elements of an initial assessment in the PACU are presented in Box 10-2.

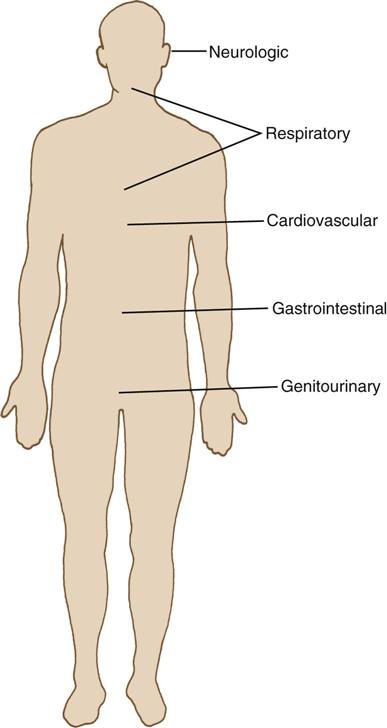

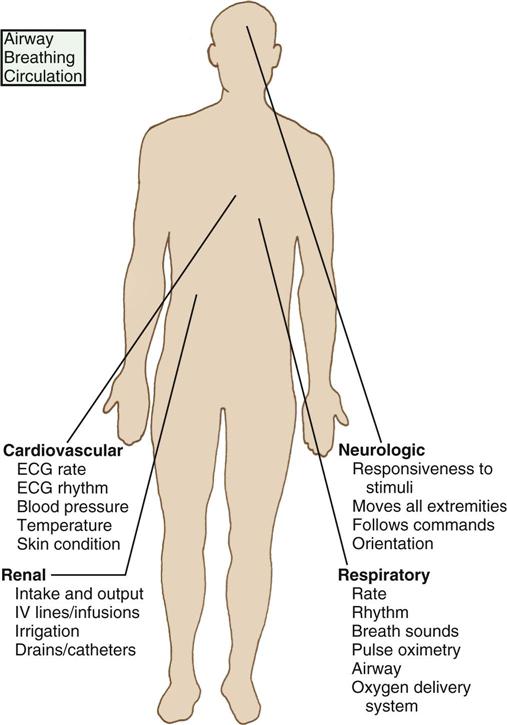

Some PACUs use a head-to-toe assessment to organize the data obtained (Figure 10-1). Other PACUs take a major body systems approach (Figure 10-2). In any case, the PACU nurse assesses admitting vital signs and the ABCs, beginning with the respiratory system. Respiratory assessment comprises rate, rhythm, auscultation of breath sounds for ventilatory adequacy, oxygen saturation level, and end-tidal CO2 level if applicable. Any artificial airway and type of oxygen delivery system are noted.

The PACU nurse next assesses the cardiovascular system by monitoring heart rate and rhythm. The patient’s initial blood pressure is compared with one or more preoperative readings. Body temperature is obtained, skin condition examined, and peripheral pulses checked, if indicated. Next, the PACU nurse assesses neurologic function by asking the following: Has the patient reacted (awakened from anesthesia)? Can the patient follow commands? Is the patient oriented, at least to name and hospital? Can the patient move all extremities and lift the head? Are there deviations from preoperative neurologic functioning? Some operative procedures require a more detailed assessment.

To assess renal function, the PACU nurse measures intake and output. Total intraoperative fluid intake and estimated blood loss are reviewed. Intravenous (IV) lines, infusions, and irrigation solutions are noted and recorded. Any drains or catheters are listed; their output is noted for color, amount, and consistency.

The surgical site is checked, noting any drainage on the bandage, including amount and color. The area around the incision is inspected so that any future changes may be compared. Patients undergoing vaginal hysterectomy require that the abdomen be assessed for firmness. A rigid abdomen may indicate hemorrhage. Noting firmness of the abdomen on admission and later findings of a rigid abdomen leads to important comparisons. The patient is also assessed for signs or symptoms of pain, discomfort, or nausea, and medicated appropriately.

Information obtained from the admission assessment is documented in the PACU record.

Nursing Diagnosis

Common nursing diagnoses related to the care of postanesthesia patients include the following:

Outcome Identification

Outcomes identified for the selected nursing diagnoses can be stated as follows:

Planning

When nursing diagnoses and desired outcomes are identified for the postoperative patient, a plan of care is designed that considers specific patient needs. Some nursing diagnoses are appropriate for all postanesthesia patients. A Sample Plan of Care for a patient in PACU is on p. 273.

Implementation

The nurse in the PACU continually assesses the patient and implements interventions for care. In addition to constant vigilant monitoring discussed under assessment, the perianesthesia nurse often begins a stir-up regimen that helps minimize complications. The stir-up regimen includes deep breathing exercises, coughing, positioning, mobilization, and pain management to facilitate respiratory function (O’Brien, 2013a). Oxygen delivery is monitored and decreased as per patient condition and PACU orders. In some cases, the patient may have entered the PACU with a capnograph in place, so the nurse monitors end-tidal CO2 and intervenes when ventilation is inadequate.

The PACU nurse monitors blood pressure and heart rate to assess cardiovascular function and cardiac output throughout the patient stay. The nurse will also provide interventions to maintain adequate normothermia and pain management. Throughout postanesthesia care, dangerous and life-threatening changes can occur rapidly (see Perianesthesia Complications).

Evaluation

The PACU nurse evaluates the identified patient outcomes prior to discharge from PACU. For the outcomes presented previously in this chapter, these might be stated as follows:

Perianesthesia Complications

The following complications are pertinent to the care of all patients during the immediate postoperative period. Three of the most common complications in the PACU are upper airway obstruction, hypotension, and nausea and vomiting (Nicholau, 2009). Prompt recognition and immediate intervention are imperative for the well-being of PACU patients.

Respiratory

Airway Obstruction.

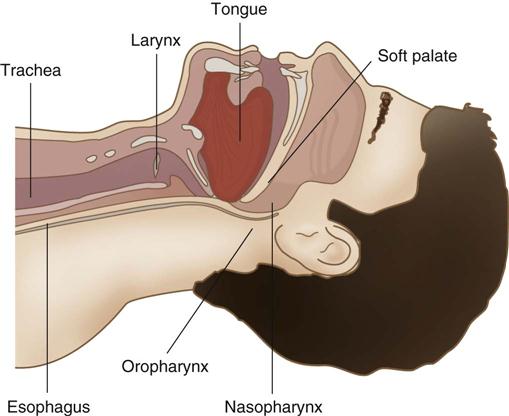

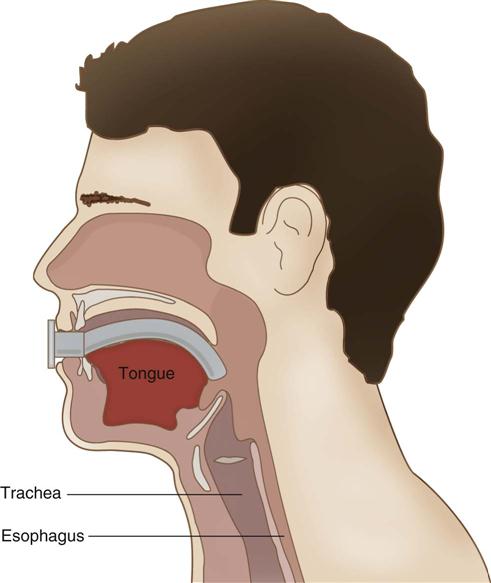

The first priority in the care of the postanesthesia patient is to establish a patent airway. A common cause of airway obstruction is the tongue, which is relaxed because of anesthetic agents and muscle relaxants used during surgery (Nicholau, 2009) (Figure 10-3). The patient may present with snoring, little or no air movement on auscultation of the lungs, retraction of intercostal muscles, asynchronous movements of the chest and abdomen, and a decreased oxygen saturation level. The nursing action taken may be simple, such as stimulating the patient to take deep breaths, positioning the patient on the side, or providing supplemental oxygen. If the patient is still unresponsive, the nurse may need to open the airway with a chin tilt or jaw thrust. A chin tilt is accomplished by lifting the chin with one hand while tilting the forehead back with the other. A jaw thrust is accomplished by displacing the temporomandibular joint forward bilaterally. The patient also can be repositioned on the right side. This position is called the recovery position. Placing the patient in this position allows the tongue to move forward and the airway to remain open.

If these actions do not open the airway, an artificial airway may need to be inserted. An oral or nasal airway may be used. An oral airway is used with an unresponsive patient (Figure 10-4). A nasal airway, better tolerated by an awake patient, is indicated for patients who are arousable.

Hemorrhage after neck surgery or carotid endarterectomy also can cause acute obstruction of the airway. The PACU nurse assesses such patients carefully for bleeding. In situations such as apnea, intubation with ventilation may be required. If intubation is impossible, the patient may require a tracheostomy, although this rarely is needed.

Laryngospasm.

A serious PACU complication is laryngospasm, usually the result of an irritable airway. Laryngeal obstruction may occlude the airway as a result of partial or complete spasm of the intrinsic or extrinsic muscles of the larynx. The muscles of the larynx contract and the vocal chords either partially or completely obstruct the airway; the patient can become hypoxemic quickly (Drain, 2013). With laryngospasm, remove the irritating stimulus, suction secretions that may be triggering a glottic response, hyperextend the patient’s neck, oxygenate the patient, and prepare to administer an aerosol with racemic (optically inactive) epinephrine. An awake patient experiencing a laryngospasm is terrified and needs reassurance and a calm demeanor from nurses and physicians. In many cases, positive-pressure ventilation is delivered by mask and bag. If symptoms last longer than 1 minute and are unrelieved by positive pressure, administration of a muscle relaxant, such as succinylcholine, by the anesthesia provider is required to relax the muscles of the larynx (Drain, 2013). Reintubation is undesirable and used only as a last resort.

Bronchospasm.

Bronchospasm is a lower airway obstruction caused by spasms of the bronchial tubes. These spasms can cause complete airway closure because of lack of cartilaginous support in the bronchioles. The patient presents with wheezing, dyspnea, use of accessory muscles, and tachypnea (Odom-Forren, 2014). Bronchospasm can result from aspiration, pharyngeal suctioning, or histamine release secondary to allergic response or related to medication use. Inhaled bronchodilators are the first choice of therapy for these patients, followed by IV aminophylline. Both IV and inhaled lidocaine can ease bronchospasm induced by histamine (Benca, 2007). If bronchospasm becomes life threatening, epinephrine may be administered. Steroids, such as methylprednisolone, also may be administered if the underlying cause is inflammatory disease (e.g., asthma).

When obstruction occurs, partial pressure of arterial carbon dioxide (PaCO2) increases significantly and quickly. With obstruction, the PACU nurse makes a quick assessment, rapidly intervenes with airway assistance, and calls for help from the anesthesia provider.

Cardiovascular

Cardiovascular system instability is a frequent finding after surgery because many anesthetic agents exert a depressive effect on the heart and vascular system. Common problems include hypotension, hypertension, and dysrhythmias. A rare complication in the PACU is cardiopulmonary arrest. Essential components of competent nursing care in the PACU includes early clinical response to signs and symptoms of complications and maintenance of resuscitation skills (Tallman et al, 2011).

Hypotension.

Hypotension has been defined as a blood pressure reading that is 20% less than baseline or preoperative blood pressure measurement; it indicates either relative or absolute hypovolemia (O’Brien, 2013b). Clinical signs of hypotension include a rapid, thready pulse; disorientation; restlessness; oliguria; and cold, pale skin. Because hypovolemia is the most common cause of postoperative hypotension, the initial intervention is to administer IV fluids (physiologic saline or lactated Ringer’s solution) at a maximum rate while making a specific diagnosis.

Cardiac output and vascular resistance determine blood pressure. Hypotension may be caused by cardiac dysfunction (such as myocardial infarction, tamponade, embolism, ischemia, dysrhythmias, congestive heart failure, valvular dysfunction) or by medications (including anesthetic agents). In such cases, the heart no longer pumps effectively. Hemodynamic monitoring, supplemental oxygen, and cardiac stimulants are used as needed.

Hypovolemia.

Hypovolemia reduces cardiac output and may be caused by hemorrhage, dehydration (inadequate fluid replacement), or increased positive end-expiratory pressure (PEEP). Fluid or blood replacement is used to treat hypovolemia. If the patient is hemorrhaging at the surgical site, a return to the operating room (OR) is indicated.

Decreased vascular resistance, which causes relative hypovolemia (interference with venous return to the heart), can be related to medications, general and regional anesthesia, or anaphylaxis (Odom-Forren, 2014). Vasodilation can be treated with fluids, vasopressors, or by elevating the patient’s legs. Anaphylactic reactions are treated with epinephrine, antihistamines, and additional fluids.

Hypertension.

The normal ranges for systolic and diastolic blood pressures are generally accepted as 100 to 140 mm Hg and 60 to 95 mm Hg, respectively, although these ranges vary. Hypertension has been defined as a 20% to 30% increase above baseline blood pressure measurement or persistent elevation of systolic blood pressure greater than 140 or diastolic pressure greater than 90 (O’Brien, 2013b; Odom-Forren, 2014). Hypertension is among the most common postoperative complications and often occurs early in the recovery phase. Blood pressure must be verified and rapidity of its change noted. Clinical signs and symptoms are the most important indicators of the severity of the hypertension. Headache, mental status changes, and substernal pain are all indicators of end-organ damage. Hypertension may be caused by volume overload or pulmonary edema, which causes an increase in the cardiac output. In this case the patient is given diuretics, placed on fluid restriction, and hemodynamically monitored. The patient with a history of cardiac disease is more at risk for adverse results.

Asymptomatic hypertension commonly occurs in the PACU and is usually considered harmless. The solution usually is determined by the cause. Patients with a history of essential hypertension are more likely to experience systemic hypertension in the PACU (Nicholau, 2009). Pain is one of the most common causes of hypertension. Other causes of hypertension are anxiety, reflex vasoconstriction from hypothermia, hypoxemia, hypercapnia, and viscus distention, all of which cause increased vascular resistance. Patients in pain are medicated, and patients with hypothermia are warmed. Patients are oxygenated and ventilated if necessary to improve hypoxemia or hypercapnia. Patients are encouraged to void or are catheterized to empty a full bladder.

Antihypertensive drugs are used as necessary to control blood pressure. Beta-blockers and α2-agonists may be used postoperatively when needed. Other agents are available and may include the patient’s usual prescription for hypertension (Odom-Forren, 2014). Patients who were on beta-blockers prior to surgery should be given a beta-blocker the day of surgery. Surgery patients receiving a beta-blocker during the perioperative period is one of the Surgical Care Improvement Project (SCIP) measures evaluated during the perioperative period (TJC, 2013). Patients should resume taking prescribed preoperative antihypertensives as soon as possible after surgery. Ambulatory surgery patients and inpatients usually are directed to take their prescribed antihypertensives on the day of surgery.

Dysrhythmias.

Most dysrhythmias seen in the PACU have an underlying cause that is unrelated to myocardial injury (Odom-Forren, 2014). A common dysrhythmia after surgery is sinus tachycardia (rate >100 beats/min in an adult). Frequent causes include pain, hypoxemia, hypovolemia, increased temperature, and anxiety. The underlying cause of the dysrhythmia is treated. Propranolol, metoprolol, or esmolol may be given. Sinus bradycardia (heart rate <60 beats/min in an adult) also is a common dysrhythmia in the PACU. Causes include hypoxemia, hypothermia, high spinal anesthesia, vagal stimulation, and some medications commonly given during or after surgery. The underlying cause of the bradycardia is treated. Atropine is the drug of choice to increase heart rate, and usually no other treatment is required. Temporary or permanent pacemakers sometimes are required.

Premature ventricular contractions (PVCs) are represented by wide, bizarre-looking QRS complexes. The most common causes in the postoperative period are hypoxemia and hypokalemia, which are treated. Often, if cardiac disease or hypotension is not present, PVCs do not require medication.

Treatment of dysrhythmias begins with determining and removing the source of the problem. The urgency of treating cardiac dysrhythmias depends on the patient’s underlying condition; dysrhythmias are most harmful in patients who have a history of coronary heart disease (Nicholau, 2009). Antidysrhythmic drugs, resuscitation equipment, and monitoring equipment should be immediately available.

Thermoregulation and Temperature Abnormalities

Hypothermia.

Postoperative hypothermia, defined as a temperature less than 96.8° F (36° C) (Hooper et al., 2010), continues to be a widespread PACU problem. While hypothermia may not be life threatening, it does cause physiologic stress. Hypothermia can prolong recovery time and contribute to postoperative morbidity. Especially vulnerable to the effects of hypothermia are the elderly and children 2 years old or younger. Other risk factors include female gender, burn patients, patients who received general anesthesia with neuraxial anesthesia, low ambient temperature of the OR, length and type of surgical procedure, cachexia, significant fluid shift, and use of cold irrigants. The prevention and management of unplanned perioperative hypothermia remain a national priority in preventing surgical site infection, and it has been designated as an SCIP quality measure (Langham et al, 2009; TJC 2013).

Assessing the need for prewarming begins preoperatively. Preventive warming measures are begun for normothermic patients and active warming measures instituted for hypothermic patients (Hooper et al, 2010).

Prevention of heat loss continues in the OR. Under general anesthesia patients do not produce heat and depend on ambient temperature. Prevention of heat loss includes increasing the ambient temperature in the OR, providing the patient with warm blankets on arrival in the OR, and using draping techniques that minimize exposure during the procedure. Heated humidifiers and fluid warmers add heat. A common device to prevent hypothermia in the OR is a forced-air warming device (Figure 10-5).

In the PACU tremendous demands are made on the body when the patient shivers. Shivering can increase the need for oxygen by 300% to 400%. Hypothermic patients should have oxygen therapy initiated immediately on admission. For a patient with a healthy heart, there may be no harmful effects. For a patient with coronary artery disease or cardiomyopathy, however, decompensation can occur. Perioperative hypothermia has been associated with increased incidence of cardiac incidents including myocardial ischemia and myocardial infarction (Nicholau, 2009).

Other problems associated with hypothermia include intravascular volume loss attributable to a fluid shift from the extracellular space, probably related to vasoconstriction (Reynolds et al, 2008). As the patient begins to rewarm, vasodilation follows, and the patient can require large amounts of IV fluids to avoid hypovolemia. The central nervous system is depressed by hypothermia. A cold postanesthesia patient remains more anesthetized than a warm patient while recovering. Nitrogen loss and hypokalemia can cause a predisposition to wound infection. Impaired wound healing and surgical site infection have been linked to hypothermia (Paulikas, 2008).

Hypothermia slows metabolism and alters the effects of some anesthetic drugs. Of special interest is the prolonged elimination of muscle relaxants in hypothermic patients. Clotting abnormalities can occur. Platelet activity declines, and fibrinolysis increases with hypothermia; both conditions enhance the tendency to bleed (Hooper, 2013).

Rewarming is a priority for the postoperative patient. Wet and cold gowns and blankets are removed, and warm, dry gowns and blankets are applied to the head and body. Several external rewarming techniques are available. Application of warm cotton blankets has been a PACU tradition. Warm blankets are applied every 5 to 10 minutes until the patient is normothermic. Cotton blankets gradually increase the patient’s temperature. They do not actively heat patients, however, and warming can be a slow process. Forced-air warming devices are effective in rewarming patients. They produce a thermal-focused environment that transfers heat by blowing warm air through a plastic and tissue paper blanket that covers the patient. Forced-air warming devices are standard hypothermia treatment in PACU settings. This is an evidence-based nursing initiative that actively decreases hypothermia (Hooper et al, 2010).

There is some evidence that continuous fluid-circulating blankets or warm-water mattresses, radiant heat lamps, gel pads, and resistive heating work (Hooper et al, 2010). Continuous fluid-circulating blankets may not work as well because the size of the surface area in contact with the heat source is limited. Radiant heat lamps depend on exposure of large areas of body surface and are of limited use to adult patients. Fluid and blood warmers are useful for large volumes of cool fluids, but not to reverse hypothermia. Single strategies such as forced-air warming were more effective at increasing temperature than passive warming as determined by one systematic review; however, combined strategies, including use of preoperative prewarming, use of warmed fluids, forced-air warming, and other active strategies were more effective in vulnerable groups (Moola and Lockwood, 2011).

Studies have explored the best method to obtain accurate temperatures in the PACU when invasive core temperature measures (e.g., pulmonary artery, distal esophagus, nasopharynx, and tympanic membrane) are unavailable. A study comparing eight noninvasive techniques to bladder temperature (Langham et al, 2009) concluded that the most accurate method for routine postoperative temperature monitoring was via electronic oral temperature devices.

Hyperthermia.

Hyperthermia may indicate an infectious process, sepsis, or a serious hypermetabolic process—malignant hyperthermia (MH). MH is a life-threatening emergency that is genetic in origin (Rosero et al, 2009). It is triggered by volatile anesthetic agents and the depolarizing muscle relaxant succinylcholine. Death may ensue unless MH is immediately recognized and treated (see Chapter 5 for a discussion of MH). Some institutions have crisis checklists in the PACU and OR to guide staff step by step thorough emergencies such as MH (Arriaga et al, 2012).

Disturbances in Cognitive Function

PACU patients may be disoriented, drowsy, confused, or delirious. Attempts have been made to differentiate emergence delirium from agitation, with agitation defined as mild restlessness and mental distress. Causes of agitation range from residual effects of anesthetics to pain and anxiety. Hypoxemia is ruled out first; it remains the most common cause of postoperative agitation. Chemically dependent patients often awaken in an agitated state. Viscus distention also can contribute to agitation in a drowsy, confused patient. The PACU nurse should identify and eliminate the cause of the agitation or confusion, if possible. The patient can be engaged in short conversations and reoriented to place and person. Baseline preoperative data are important to determine the cause of agitation. Persistent changes from preoperative status require thorough assessment and possible intervention by the physician.

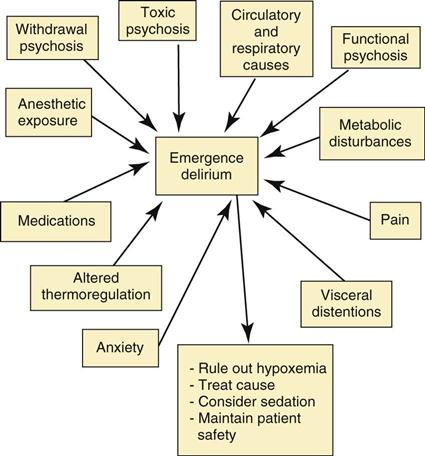

McGuire and Burkard (2010) identified pain and trauma, both physical and psychologic, as potential risk factors for emergence delirium in military personnel. In another study, patients who were less than 75 years of age and had a pain level of less than 4 were more likely to recover from delirium (Decrane et al, 2011). These authors point out that aggressive pain management may be the key in facilitating early recovery from delirium. Figure 10-6 provides a summary of factors contributing to emergence delirium and treatment options.

Nausea and Vomiting

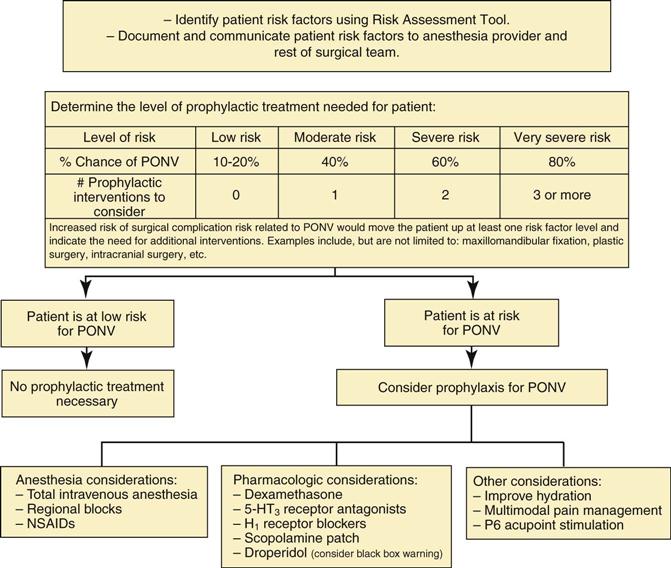

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a problem that affects approximately 30% of PACU patients (Fetzer, 2010). Primary risk factors associated with PONV are female gender, nonsmoker, history of PONV or motion sickness, use of volatile anesthetics, use of nitrous oxide, postoperative use of opioids, duration of surgery, and type of surgery (Gan et al, 2007). Patients with four or more risk factors have a higher incidence of PONV. Management of nausea and vomiting begins preoperatively and continues into the intraoperative period. Preventive therapy for patients at high risk of PONV is effective in reducing its incidence. There is no single method to prevent or treat PONV. Many causative factors relate to anesthesia and surgery. Pharmacologic prophylaxis improves patient comfort, readiness for discharge, and satisfaction with care (Practice Guidelines, 2013).

Risk factors for PONV should be assessed preoperatively and care planned accordingly. Two risk assessment tools commonly are used. Apfel and colleagues (1999) developed their risk assessment tool based on four risk factors: female gender, smoking status, history of PONV or motion sickness, and postoperative use of opioids. Koivuranta and colleagues (1997) identified five risk factors: surgery lasting more than 60 minutes, female gender, history of motion sickness, history of PONV, and nonsmoking status. Figure 10-7 lists guidelines regarding preoperative management and prophylaxis of PONV.

Receptors that can cause nausea and vomiting when triggered are dopamine type-2, serotonin type-3, histamine type-1, muscarinic cholinergic type-1, and neurokinin type-1. Patients at risk for PONV receive either one or a combination of agents that block one or more of these receptor sites (Surgical Pharmacology). Effective medications are aprepitant (Emend), ondansetron (Zofran), dolasetron (Anzemet), granisetron (Kytril), promethazine (Phenergan), prochlorperazine (Compazine), dexamethasone, palonosetron (Aloxi), and transdermal scopolamine. Other medications that can be considered are metoclopramide (Reglan) at a dosage of at least 25 to 50 mg IV, dimenhydrinate (Dramamine), diphenhydramine (Benadryl), or droperidol (Inapsine). Droperidol has a black box warning; the patient must be monitored for QT prolongation/torsades de pointes after administration (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2001). If the patient is hypotensive with nausea and vomiting, ephedrine and additional fluids may be administered. PONV rescue medication administered in the PACU should be an antiemetic from a different pharmacologic class than medication given for prophylaxis (Apfel, 2009). Figure 10-8 reviews postoperative management of the patient with PONV.

Surgical Pharmacology

Antiemetic Pharmacology

| Agent | Receptors Affected | Route and Dosage | Comments |

| Aprepitant (Emend) | NK1 | 40 mg PO | Patient should receive 1-3 hours before surgery. |

| Dexamethasone (Decadron) | ? | 4 mg IV | Administer before induction. |

| Dimenhydrinate (Dramamine) | H1, M1 | 50-100 mg IV, IM | Side effects include dry mouth, urinary retention. |

| Diphenhydramine (Benadryl) | H1, M1 | 12.5-25 mg IM, IV | Side effects include dry mouth, urinary retention. |

| Dolasteron (Anzemet) | 5-HT3 | 12.5 mg IV | |

| Droperidol (Inapsine) | D2 | 0.625-1.25 mg IV | Use requires ECG monitoring for 3 hours after dose. |

| Graniseteron (Kytril) | 5-HT3 | 5 mcg/kg-1 mg IV | |

| Metoclopramide (Reglan) | D2 | 10 mg IV | Increases GI motility; no effective prophylaxis. |

| Ondansetron (Zofran) | 5-HT3 | 4 mg IV or ODT | Give 15-30 minutes before end of surgery. |

| Prochlorperazine (Compazine) | D2 | 5-10 mg IV, IM | Side effects include dry mouth, urinary retention. |

| Promethazine (Phenergan) | D2, H1, M1 | 6.25 mg-12.5 mg IV; 12.5-25 mg IM; PR | Extrapyramidal symptoms possible. |

| Scopolamine (Transderm Sco¯p) | H1M1 | 1.5-mg transdermal patch | Apply 4 hours before end of surgery; anticholinergic effects. |

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree