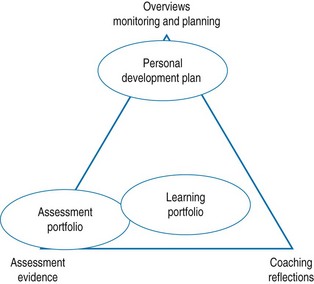

Chapter 39 We will especially focus on the assessment of portfolios. In an earlier publication we focused on the portfolio as a coaching method (Driessen et al 2010). The assessment principles and strategies we will describe in this chapter not only apply to portfolios but have broader applications. They can also be used for other complex assessments, such as assessment of projects or papers, such as a master’s thesis. • Guiding the development of competencies. The learner is asked to include in the portfolio a critical reflection on his or her learning and performance. The minimal requirement for this type of portfolio is the inclusion of reflective texts and self-analyses. • Monitoring progress. The minimum requirement for this type of portfolio is that it must contain overviews of what the learner has done or learned. This may be the numbers of different types of patients seen during a clerkship or the competencies achieved during a defined period. • Assessment of competency development. The portfolio provides evidence of how certain competencies are developing and which level of competency has been achieved. Learners often also include an analysis of essential aspects of their competency development and indicate in which areas more work is required. This type of portfolio contains evidential materials to substantiate the level that is achieved. Most portfolios are aimed at a combination of goals and therefore comprise a variety of evidence, overviews and reflections (Fig. 39.1). Portfolios thus differ in objectives, and the objectives determine which component of the portfolio content is emphasized. Portfolios can also differ in scope and structure (Van Tartwijk et al 2003). Portfolios can be wide or narrow in scope. A limited scope is appropriate for portfolios aimed at illustrating the learner’s development in a single skill or competency domain or in one curricular component. An example is a portfolio for communication skills of undergraduate students. A portfolio with a broad scope is aimed at demonstrating the learner’s development across all skills and competency domains over a prolonged period of education. At the end of this chapter we will describe an example of this type of portfolio. We have explained that portfolios can contain overviews, evidential materials and reflection. We have located these elements on the corners of a triangle (Fig. 39.1). We will now focus on the format and place of each of these elements in the portfolio. • Procedures or patient cases. Which procedures? What was the level of supervision? Which types of patients? What was learned? Were the activities assessed? Plans? • Prior work experience. Where? When? Which tasks? Strengths and weaknesses? Which competencies or skills were developed? Evaluation by the learner? • Prior education and training. Which courses or programmes? Where? When? What was learned? Completed successfully? Evaluation by the learner? • Experiences within and outside the course/programme. Where? When? Which tasks? What was done? Strengths and weaknesses? Which competencies or skills were developed? Evaluation by the learner? Plans? • Components of the course/programme. Which attended at this point? Which not (yet) attended? When? What was learned? Completed successfully? Evaluation by the learner? Plans? • Competencies or skills. Where addressed? Level of proficiency? Plans? Preferences? Portfolios can contain a variety of of materials. We distinguish three different types: • Products, such as reports, papers, patient management plans, letter of discharge, critical appraisals of a topic • Impressions, such as photographs, videos, observation reports • Evaluations, such as test scores, feedback forms (e.g. Mini-CEX), letters from patients or colleagues expressing appreciation, certificates. Despite the simplicity of the portfolio concept – a learner documents the process and results of his or her learning activities – the portfolio has proved to be not invariably and automatically effective. The literature on portfolios shows mixed results. The key question here is what makes a portfolio successful in one situation and less successful in another situation? A number of reviews have shed light on some key factors (Buckley et al 2009, Driessen et al 2007, Tochel et al 2009).

Portfolio assessment

Introduction

The objectives and contents of portfolios

Overviews

Materials

Success factors for portfolios

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Basicmedical Key

Fastest Basicmedical Insight Engine