Pneumonectomy: Open

Christopher R. Morse

Cameron T. Stock

DEFINITION

Pneumonectomy is the complete removal of a lung. A pneumonectomy is most often performed for bronchogenic carcinomas that are central and unable to be removed via a lesser (lobectomy, segmentectomy) resection.

PATIENT HISTORY AND PHYSICAL FINDINGS

A thorough history should be obtained on all patients presenting with a new lung mass. Patients may have symptoms of dyspnea, cough, hemoptysis, or weight loss. Some patients, however, may present with a mass or hilar fullness discovered incidentally on routine chest x-ray.

The history should focus on signs and symptoms of local or distant metastases. Patients should be asked about recent onset of headaches or other neurologic symptoms, which should arouse suspicion for distant metastases. Patients should also be questioned about new chest wall or back pain, suggesting local tumor invasion or distant bony metastases.

It is essential to establish the patient’s functional status prior to pneumonectomy. There are several scales that can be used to quantify a patient’s performance status including the Zubrod and Karnofsky scales. Poor functional status is a contraindication to pneumonectomy. Age is not a contraindication to pneumonectomy; however, older patients must be carefully selected as increasing age has been associated with increased postoperative complications. Patients should also be asked about significant cardiac history and other medical comorbidities.

A history of smoking or significant exposure to secondhand smoke should be noted in the patient’s history or significant environmental exposures such as to silicon, asbestos, or radon. Active smokers are often not considered operative candidates.

On physical exam, auscultation of the lungs revealing diminished breath sounds suggests a near obstructing lesion or a significant pleural effusion. Findings of Horner’s syndrome suggest involvement of the sympathetic ganglion. Hoarseness can indicate invasion of the recurrent laryngeal nerve (RLN). Evaluation of the supraclavicular and cervical lymph nodes (LNs) should be performed with enlarged nodes suggesting metastatic disease.

IMAGING AND OTHER DIAGNOSTIC STUDIES

Routine chest x-rays may reveal a hilar mass or hilar fullness. Chest x-rays are limited, however, they may show lobar collapse, pleural effusions suspicious for a malignant effusion, or elevation of the diaphragm suggesting phrenic nerve involvement.

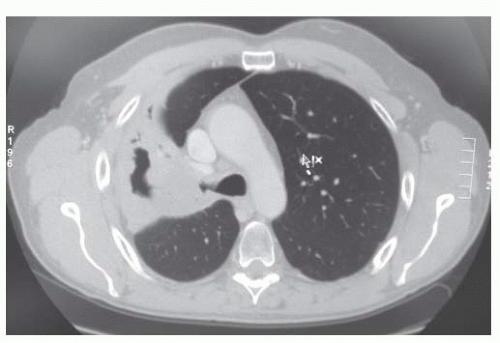

A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest should be obtained for all patients being evaluated for possible pneumonectomy (FIG 1). If available, prior CT scans should be used for comparison. A CT scan of the chest can be used to assess staging of the primary lesion, degree of local chest wall, or mediastinal invasion. The presence of hilar or mediastinal lymphadenopathy should be noted. CT may understage mediastinal LN by missing LNs positive for metastatic disease that are not enlarged or greater than 1 cm. Therefore, a CT chest alone is not sufficient for preoperative staging.

Positron emission tomography (PET)/CT should be performed to confirm metabolic activity in the primary lesion, to assess for distant metastases, and to increase the ability to detect nodal involvement. PET/CT has a high false-positive rate; therefore, suspicious lesions on PET should be confirmed with a tissue diagnosis.

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the brain is used to assess for distant metastases that are not able to be imaged on PET/CT and should be obtained for all patients with central lesions.

Pulmonary function tests (PFTs) are necessary to define the patient’s ability to tolerate a pneumonectomy. In general, postoperative calculated forced expiratory volume (FEV1) of less than 40% predicted or a diffusing capacity of the lung for carbon monoxide (DLCO) less than 40% predicted are significant predictors of morbidity and mortality following pneumonectomy and should be used to guide candidate selection.

FIG 1 • CT scan of chest demonstrating a right hilar mass causing partial lobar collapse of the right upper lobe.

In patients with marginal PFTs, a ventilation-perfusion (V/Q) scan should be obtained. Patients with large proximal tumors compromising lung function may have compensated through shunting and therefore may better tolerate a pneumonectomy than would be predicted based on their preoperative PFTs. Other cardiopulmonary testing such as maximum oxygen consumption (Vo2max) can be used to evaluate patients who are marginal candidates for resection.

Patients with a Vo2max less than 15 mL/kg/min and a postoperative predicted FEV1 and DLCO less than 40% are at high risk for postoperative complications.1

A cardiac workup including an electrocardiogram (EKG) and an echocardiogram and stress test in patients with significant risk factors for coronary artery disease should be performed. Patients with signs of right heart failure or pulmonary hypertension are at high risk for mortality postoperatively.

Routine lab work including liver function tests and alkaline phosphatase should be obtained.

A tissue diagnosis of the primary lesion is helpful in the preoperative planning and staging for a lung resection. Patients with small cell lung cancer lesions are not candidates for pneumonectomy. Due to proximity to hilar structures, a CT-guided fine needle aspiration (FNA) may be technically challenging. When tumors are intraluminal and visible on flexible bronchoscopy, biopsies can easily be obtained. Other modalities such as endobronchial ultrasound (EBUS) FNA or navigational bronchoscopy can be used to biopsy a hilar mass if not visible on flexible bronchoscopy.

Mediastinoscopy and LN biopsy should be performed on all patients considered for pneumonectomy. Patients with enlarged mediastinal LN on CT or have increased metabolic activity on PET/CT have a high likelihood of having mediastinal LN metastases. Mediastinal LN involvement (N2 disease) may lead to neoadjuvant chemoradiotherapy.

SURGICAL MANAGEMENT

Preoperative Planning

Active smokers should be counseled to quit smoking weeks in advance, as smoking has been found to be an independent risk factor for adverse outcomes.2

A thoracic epidural catheter should be placed prior to surgery unless there is a contraindication.

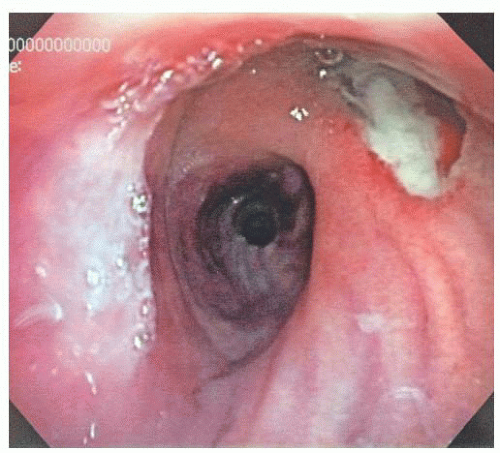

Prior to surgery, all patients should undergo flexible bronchoscopy by the operating surgeon to assess resectability. On flexible bronchoscopy, the location of the tumor with respect to the trachea and main bronchus should be assessed (FIG 2). Copious respiratory secretions may warrant a course of antibiotics to treat pneumonia prior to pneumonectomy.

CT chest images should be reviewed, and final planning for the procedure should occur.

The patient should have an active type and screen and have blood available in the blood bank, and antibiotics should be administered prior to skin incision.

An arterial line should be placed prior to incision.

Communication between the surgeon and anesthesiologist is critical. Excessive intravenous (IV) fluid administration in the perioperative period (particularly intraoperative and postoperative) is associated with acute lung injury in patients undergoing pneumonectomy.

High tidal volumes during single-lung ventilation have been linked to increased rates of respiratory failure postoperatively. Low tidal volume ventilation (5 to 6 mL/kg) to prevent barotrauma is preferred with peak inspiratory pressures not to exceed 35 cm H2O and plateau pressures to remain below 25 cm H2O.3

Positioning

Patients are intubated with a double lumen tube and positioned in the lateral decubitus position with the surgery side up. Rolled blankets or a “beanbag” are used to hold the patient upright. An arm board or ether screen can be used to support the arms. All pressure points should be well padded with particular attention paid to the common peroneal nerve. An axillary roll may be used to support the axilla. The bed is flexed and the patient should be secured to the bed with heavy tape and a belt (FIG 3).

TECHNIQUES

RIGHT PNEUMONECTOMY

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree