A. Heart

1. The heart increases in size during aging as a result of concentric ventricular hypertrophy that occurs in response to the increase in left ventricular afterload.

2. The heart rate response to severe exercise is diminished (increases in cardiac output in response to severe exertion are attenuated by approximately 20% to 30%).

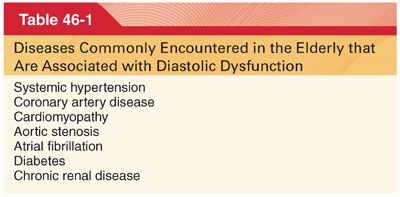

3. Cardiac dysfunction in aging is largely related to impaired diastolic left ventricle function with increased prevalence of diastolic heart failure exacerbated by several coexisting diseases (Table 46-1).

4. Tachycardia and shortened diastolic intervals are associated with marked decreases in ventricular preload in the elderly. Atrial fibrillation is a common rhythm in the elderly. Loss of the atrial “kick” is particularly poorly tolerated by elderly patients.

5. Perioperative events that reduce venous return, such as hypovolemia, positive pressure ventilation, and increased venous capacitance, may be accompanied by significant decreases in cardiac output.

6. Dyspnea in the elderly may indicate congestive cardiac failure and/or pulmonary disease.

B. Large Vessels

1. Structural changes in the large vessels (elongated, tortuous, dilated, intima thickened) are an important element of the aging process and contribute significantly to the age-related changes in the heart.

2. In the elderly, the pulse wave is reflected back from the peripheral circulation and augments systolic pressure. Diastolic pressure tends to be lower in the elderly than in younger individuals (pulse pressure are increased and left ventricular afterload is elevated).

C. Endothelial Function. Age-related endothelial dysfunction can be characterized as a decrease in the ability of the endothelium to dilate or contract blood vessels in response to physiologic and pharmacologic stimuli.

D. Conduction System. There are several important age-related structural and functional changes in the cardiac conduction system (sinoatrial node, atrioventricular node, and conduction bundles also become infiltrated with fibrous and fatty tissue). These changes are responsible for the increased incidence of first- and second-degree heart block, sick sinus syndrome, and atrial fibrillation in the elderly.

E. Autonomic and Integrated Cardiovascular Responses

1. Aging is associated with increased norepinephrine entry into the circulation and deficient catecholamine reuptake at nerve endings (elevated circulating concentrations of norepinephrine are usual, generating chronically increased adrenergic receptor occupancy).

2. The cardiovascular response to increased adrenergic stimulation is attenuated by downregulation of postreceptor signaling and reduced contractile response of the myocardium. The number of the β-adrenergic receptors is reduced in the elderly myocardium.

3. Receptor downregulation is responsible for the age-related decline in maximum heart rate during exercise.

4. Orthostatic hypotension is common in the elderly and is associated with syncope, falls, and cognitive decline. Impaired baroreceptor reflexes and attenuated peripheral vasoconstriction are partially responsible.

F. Anesthetic and Ischemic Preconditioning in the Aging Heart. Under certain circumstances, exposure to volatile anesthetics (anesthetic preconditioning) or several brief periods of ischemia (ischemic preconditioning) may enhance tolerance to subsequent ischemia, enhance cardiac function, and reduce infarction size. Anesthetic and ischemic preconditioning may be markedly attenuated in the elderly, potentially explaining the difficulty of translating promising preclinical results to treatment.

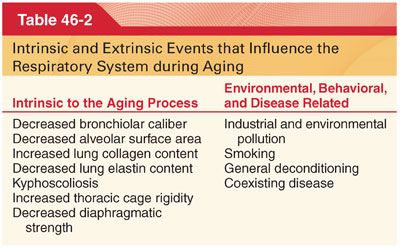

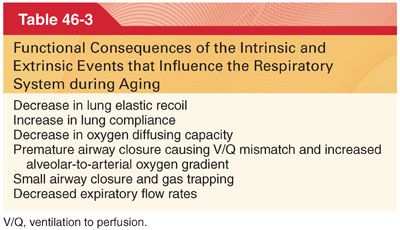

III. Aging and the Respiratory System (Tables 46-2 and 46-3). Decreased respiratory reserve may be unmasked by illness, surgery, anesthesia, and other perioperative events. Common respiratory diseases and the effects of smoking and environmental pollution frequently exacerbate the decline in respiratory function with aging (anticipation and amelioration of their effects is critically important to anesthetic management in the elderly as postoperative respiratory complications result in 40% of perioperative deaths in patient older than 65 years).

A. Respiratory System Mechanics and Architecture

1. The chest wall becomes less compliant with aging, presumably related to changes in the thoracic skeleton and a decline in costovertebral joint mobility (produce a restrictive functional impairment).

2. The diaphragm and abdominal muscles assume a greater role in tidal breathing (diaphragmatic function declines with age, predisposing the elderly to respiratory fatigue when required to significantly increase minute ventilation).

B. Lung Volumes and Capacities

1. Vital capacity (VC) is the volume generated when a maximal inspiration is followed by a maximal expiration. There is a progressive loss of VC with aging.

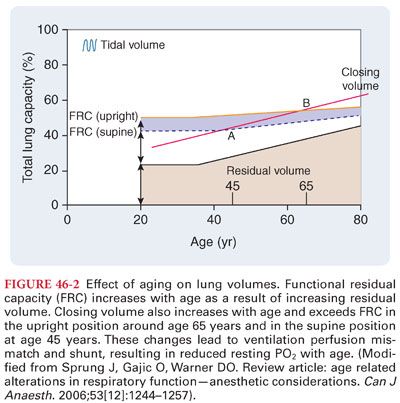

2. Residual Volume. The residual volume is the volume remaining in the lungs after a maximal expiration. Aging is associated with a progressive increase in residual volume of up to 10% per decade (Fig. 46-2).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree