The description of the current medication-use process should be developed from a number of sources: observation, paper order sets, discussion with clinicians, and the knowledge of those who have worked on the organization’s previous process-improvement efforts. This process is an opportunity to engage staff pharmacists who service various areas of the organization. Pharmacists often have a broad view of the medication-use process, seeing it from end to end, both receiving orders from physicians and helping address complex administration scheduling issues. The project team should strive to understand the current state of the medication-use process in terms of the components listed in Table 1, which also lists the form best used to represent the component.

Components of the Medication-use Process and Formats Best Suited to Representing Them | |

Component | Representation |

Activities performed | Process flow chart |

Strengths and weaknesses of the current process | Text/table |

The person(s) performing the activities | Text |

The information needed in order to perform the activitiy | Text |

The tools and systems used to perform the activity | Flow chart |

The outputs of the activity and where they are sent/recorded | Text |

The time/effort used to perform the activities’ | Text |

The barriers, constraints, reductions in efficiency, and limitations on the activity | Text |

Developing the Future Medication-Use Process and System Design

Once the current state of the medication-use process is well understood, one or more instances of the future state (depending on the plan for phasing in the CPOE system) can be designed. This future state should be designed to meet or exceed the current levels of service and other important designated metrics and priorities (e.g. patient safety, first-dose delivery time) and address any desired improvements.

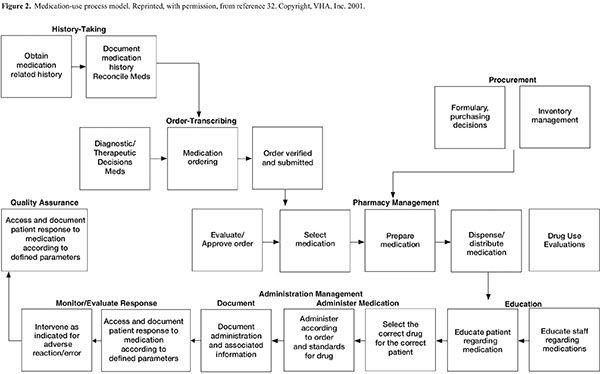

The CPOE system should be designed to support the hospital’s ideal medication-use process as much as is possible. The system should be configured to support clinicians and promote improved patient care processes, rather than compromising these processes to accommodate system functionality. It will likely be necessary (and desirable) to change many of the key work processes to ensure that benefits (such as improved medication safety) are achieved. A description of the ideal medication-use process is beyond the scope of these guidelines, but key steps in a typical medication-use process are outlined in Figure 2.

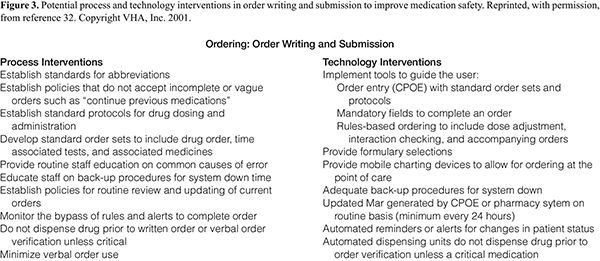

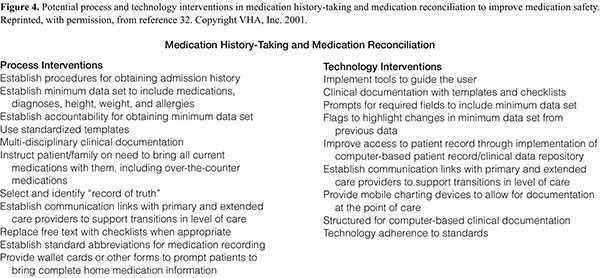

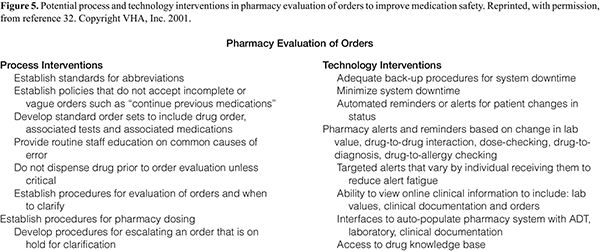

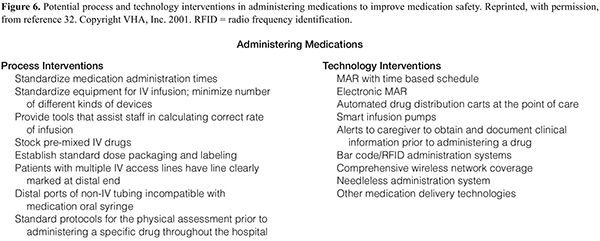

A successful CPOE design is a combination of process, information systems, and supporting technologies that work together to allow the desired improvements to occur. Figures 3–6 list some of the process and technology enhancements that should be considered for incorporation into the new process/technology/system design.

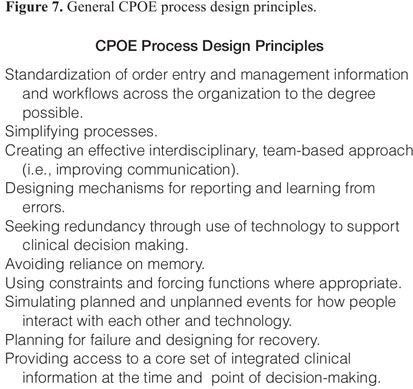

The desired benefits of the CPOE implementation should be clearly identified, and the process and system design should make those benefits possible. The design should include the practices, work processes, and technological components in an integrated fashion. General process design principles are listed in Figure 7.

The future state design should be an interdisciplinary effort that considers the entire medication-use process, even though parts of the process may not change or may not change much with CPOE implementation. It is important to maintain the continuity and integrity of the process by making sure that the design of the component activities is compatible and completely accounts for manual or previously automated processes.

The draft future state design is typically done with a small interdisciplinary group of clinicians (the “core team”) who understand the current process and the capabilities and limitations of the CPOE system. This group should consist of clinicians who order (physicians, nurse practitioners, and pharmacists), dispense (pharmacists and pharmacy technicians), and administer (nurses and physicians) medications. This core team should have dedicated time for the project, or at least be relieved of their regular staff schedules for the time spent working on the project. The charge of this group is to weave into the system design the following factors:

- Existing work processes and systems,

- Best practices,

- New systems, with consideration for their capabilities and limitations,

- Physical limitations (e.g., space, facility issues, staffing limitations),

- Political issues (e.g., organizational priorities, limited physician cooperation or interest in CPOE),

- Desired benefits and performance improvements, and

- Compliance with regulatory, legal, and reimbursement requirements.

This redesign typically starts with a high-level process flow diagram that describes the activities performed by each member in the medication-use process, coupled with demonstrations of the system capabilities and flow. Through successive iterations, the workflow and system design is brought into increasing levels of detail and expanded to address the factors listed above.34 Once the core team is satisfied with the design, practicing clinicians can be brought in to validate and improve the design. The clinicians involved in these process redesign sessions should be experienced and practicing clinicians who understand the current process and will likely find the potential issues with the new processes. These process redesign sessions should be as practically focused as possible and should demonstrate prototypes of orders and output from the system. They should provide a forum to discuss what to do and how it will be done. The redesign will likely take at least three or four sessions to cover the necessary detail of all the affected processes. The information gathered from these sessions can then be used to complete the process and system design and build the policy and procedure and training documents.

Failure Mode and Effects Analysis. A safety analysis of the future state design should be done prior to implementation to identify unintended or unidentified consequences.41 Failure mode and effects analysis (FMEA) is a useful tool to prospectively evaluate the potential risks associated with the new process and identify inconsistencies or omissions that may have the unwanted effect of increasing risk to patient safety rather than reducing it.41–44

Other Design Considerations. It should be determined whether there are required elements at provider order entry in order for the pharmacy to verify orders (e.g., patient allergies, weight). Integrated systems start to break down the silos in which physicians, nurses, and pharmacists sometimes practice. There should be one shared field for allergy and weight documentation, so any expected workflow changes need to be discussed prior to implementation. Though it is the right thing to do, this standardization often uncovers workflow issues that were previously hidden in the paper process. The current process for handling allergy conflicts or drug interactions should be examined and it should be determined how users will handle an alert in a critical or time-dependent area, such as the emergency room. It should also be determined whether there is a need for an additional set of elements for order processing (e.g., laboratory or other results).

Medication Use within the Context of CPOE and the EHR. Whether your organization implements CPOE alone or along with other parts of the EHR (such as the eMAR), other parts of the medication-use process will be affected. To meet the long-term goal of a complete EHR, all medication orders should be included in CPOE. Having disparate ordering systems (i.e., manual and electronic systems) causes confusion, creates additional work for health care professionals, and presents risks to patient safety. The hospital must recognize that CPOE may increase the amount of time the medical staff spends on prescribing medications, at least in the beginning.45,46 Therefore, there must be considerable dialogue with the medical staff about their role in the overall medication-use process. It is important that they understand that CPOE is an effective way for them to communicate their orders and improve the timeliness, accuracy, and safety of patient care and that efficiency should improve over time. The hospital should provide incentives for prescribers to utilize the system and disincentives for giving verbal orders or continuing to handwrite orders. To facilitate use of the system, prescribers should have access to the CPOE system from multiple venues, including their offices and homes and via wireless computers. If clinicians have the ability to enter orders from multiple locations such as home or office, a defined process should exist to easily reach the prescriber if there is a problem with the order (e.g., non-formulary, lack of availability).

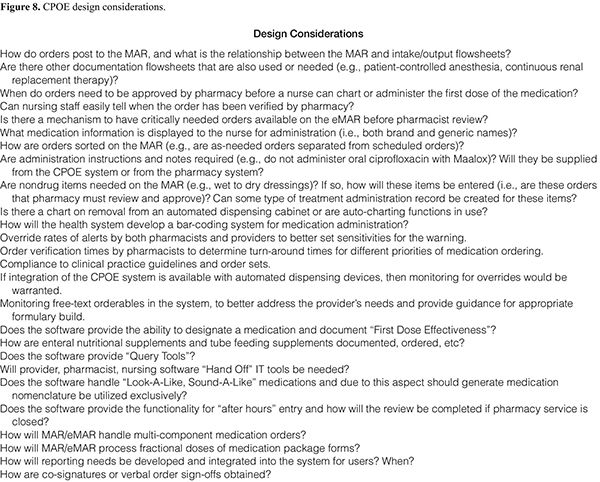

All new orders should be verified by a pharmacist and reviewed by a nurse, and these actions should be documented in the EHR prior to medication administration. The nurse should work directly in the EHR for all clinical documentation, including medication administration. To comply with the “five rights” of medication administration,47 a workstation must be available close to the patient’s bedside with ready access to that patient’s relevant information to facilitate resolution of any questions on the medications that arise. Figure 8 lists some design considerations for the workgroup as new workflows are designed for different clinical scenarios.

Computers (both wired and wireless) should be available in sufficient quantities so that no clinician has to wait to use one. It is critical that the technologies used for stationary and mobile computing be matched to the anticipated workflow. It is likely that stationary computers, handheld devices (e.g., personal digital assistants), and tablet and cart-mounted computers will all be needed for some part of medication ordering for various users. If they are not part of an integrated system, the CPOE, eMAR, and pharmacy information systems should be available on the same computer to facilitate switching between systems. Any other technologies that are used by providers (e.g., voice recognition) should not only be on the same computer but ideally available from these devices as well. Users should be able to easily switch between different applications if needed, and clinical data should freely flow between applications so that the pharmacist and other providers have real-time access to the same information.

Planning for CDS

CPOE is an important part of an organization’s plan for improved safety and quality. The addition of CDS to the EHR and CPOE is essential for the prevention of adverse events and improvement in patient outcomes.17,20,21 A full discussion of CDS is beyond the scope of this document. ASHP plans to cover the topic in future guidelines. The purpose of this section is to provide an overview of CDS that will allow incorporation of CDS to be addressed in planning.

CDS can be defined as providing the appropriate clinicians with clinical knowledge and/or patient information intelligently filtered and presented at appropriate times to enhance patient care.48 CDS has many intervention types, including but not limited to the following49:

- Documentation forms/templates (structured guidance, required or restricted fields, checklists),

- Relevant data presentation (optimize decision making by ensuring all pertinent data are considered),

- Order/prescription creation facilitators (pick-lists, pre-completed order sentences and order sets),

- Protocol/pathway support (multistep care plans, link to evidence or protocol, pertinent reference information or institution-specific best practice guidance),

- Alerts and reminders (drug–drug interactions, therapeutic duplication, drug–disease, allergy alerts, and others), and

- Automated ADE detection based on patient symptoms, labs, diagnostic results, and patient notes.

Because CDS has such a broad definition, the line between CDS and CPOE is not always clear. Basic forms of CDS, such as fully defined order sentences and order sets, are an important aspect of CPOE and can decrease errors while enhancing clinician acceptance of the system.27,28 This type of basic CDS encourages clinicians to make proper choices initially rather than alerting them to potentially problematic choices after the fact and is an essential part of any CPOE implementation.

An organization must recognize that to realize the benefits of CDS, the CPOE system must be accepted by clinicians and used effectively. Poor design or too many alerts could lead to system rejection or, even worse, unanticipated outcomes such as increased errors or adverse events.25,26,50–53

Some CDS, including checks for allergies, drug–drug interactions, drug duplications, and dose ranges, are typically delivered via an interruptive alert to the user or displayed as a passive warning on an order entry screen. Such CDS should be considered before CPOE implementation, but designers should keep in mind that a high number of interruptive alerts may cause clinicians to ignore alerts altogether and may even threaten clinician acceptance of CPOE. The way alerts are prioritized and presented to the user may be as important as which alerts are presented. Alerts for very serious clinical situations may be ignored when lost in a sea of less important ones.54 Some vendor systems allow clients to change severity levels or even disable some alerts in an effort to bring alert interruptions to a better signal-to-noise ratio and thus decrease the potential for alert fatigue, particularly for physician recipients.50–52 Ideally, there needs to be an alternative mechanism to provide CDS feedback to prescribers that is not intrusive but still allows the prescriber to know that there may be issues with an order. If ignored, these alerts can be acted upon by the pharmacist.

The strategy for prioritization of CDS should be defined as early as possible, and pharmacists should take a leading role in all medication-related CDS. It is likely that organizations will be eager to implement CDS along with CPOE. Pharmacists should ensure that the CPOE system is implemented with basic CDS, such as order sets and sentences, while using appropriate caution when implementing alerts.27 Although vendor systems are continuously improving and may allow tiering of alerts, there is typically a significant amount of work necessary to vet any changes and carry out the technical work involved in the customization. The combination of pharmacists’ clinical knowledge of drugs and their experience with the interruptive alerts that have been present in pharmacy information systems for years provide pharmacists with a unique understanding of the many implications of implementing medication-related CDS. Pharmacists should work with medical leadership, either through the P&T, informatics, or another interdisciplinary committee, to decide how and when medication-related CDS will be added to CPOE. Pharmacists are well positioned to formulate local evidence criteria, collect information on medication therapy outcomes, and to bring together institutional health providers for the purpose of setting priorities and targeted outcomes where select IT interventions are made. The design, implementation, and optimization of CDS is an exciting area of opportunity for pharmacists now and in the years to come.

Elements of a Safe CPOE System

Minimum Features and Functions. The implementation group and key stakeholders should consider what features and functions of the CPOE system are desired both now and in the future. Starting with a pilot group of users allows experience with the system to build and permits users to work through some process issues before system usage is widespread. Any pilot should be brief, with plans for a roll-out shortly after addressing the major discoveries. A highly sophisticated system may take so long to develop that interest is lost, or it may be too sophisticated or rigid in its initial application to be well accepted.

An important consideration during CPOE implementation is the determination of which functionalities are required for go-live. CPOE will always be a work in progress, and there will be opportunities for modifications and enhancements. At a minimum, the project team should evaluate all existing manual medication ordering processes, including such complex orders as epidurals, patient-controlled analgesia, weight-based dosing, lab-result-dependent dosing, tapering medication doses, total parenteral nutrition, and chemotherapy, along with critical patient safety functionality driven from known internal or external sentinel events. An agreed-upon list of basic functionality should be established in order to ensure a timely yet successful go-live. If some complex or high-risk medication orders will be left on paper at the initial go-live (e.g., chemotherapy), be sure this is well communicated during training. As well, this principle applies to other identified yet unresolved design topics. The project team will to need re-visit these topics for completion in the post-go-live period.

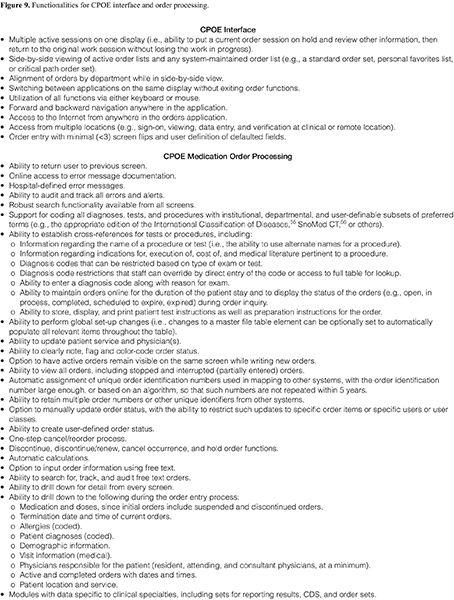

General Features and Functions. The user interface is often a problematic aspect of CPOE. Users have been reported to enter orders for the wrong patient or to select the wrong item (or wrong feature of an order) unintentionally because they did not use selection lists properly or because it is very easy to select the wrong item from a drop-down list.38 The CPOE user interface should incorporate appropriate human-factors engineering to avoid risk-prone workflows and controls (e.g., memorized mnemonic codes or function keys, long selection lists) that may produce order-entry errors. The order entry functionality should be independent of patient setting (e.g., inpatient, outpatient), and users should be able to combine data (e.g., order history) from all settings without a need for independent searches or screen selections. The system should include an online help function for system navigation and provide notification if another user modifies the patient record while an order session is ongoing, without losing the session. All displays should contain the patient name, patient location, user name, and function in consistent screen locations. The system should support third-party data entry for prescribers by simultaneous display of the same session in multiple locations and default fields where possible or helpful. The CPOE system should permit user definition of data elements and fields that can be attached to any portion of the database. The system should permit user-friendly, error-free medication order processing by providing the functionalities for the CPOE interface and order processing listed in Figure 9.

Levels of Access. The team will need to determine the levels of access or security permitted to staff throughout the hospital. The team may find it easier to begin with the current level of privileges for existing systems.

In general, pharmacists require a high level of access (full access to medication orders, and in some cases the ability place lab orders) because they cover multiple areas; place, alter, or discontinue orders; and may practice under protocols that require monitoring of laboratory test results. There may be different levels of access within the pharmacy department (e.g., actions by a pharmacy student, intern, or resident may need to be reviewed by a senior pharmacist; pharmacy technicians may require different levels of access, depending on duties). Staff may also need off-site or alternative site access.

In addition to pharmacy personnel access, the design team will need to determine levels of access for other staff members. This should include all categories of physicians that practice at the site (e.g., attendings, specialists, consultants, community clinicians with privileges, residents or other trainees, fellows, and medical students). The medical staff office, medical staff executive committees, or P&T committees may be able to make recommendations for appropriate access based on existing policies. Nursing will need to consider similar access issues and ensure compliance with provider practice acts. Ideally, these issues are addressed by existing policies that will only need to be reviewed and implemented. Other ancillary staff will need to be granted access, depending on their need for information and orders that will be built within CPOE and routed to the appropriate department for action.

User Levels and Co-Signatures. The CPOE system should permit restriction of medication orders by user type, individual order, or class of order. Each medication order should indicate the name and user level of the ordering party. The CPOE system should support the entry of unverified orders and the editing and verification of unverified orders, and this function should be role-based and restricted. The system should also support the creation of reminders or inbox messages for orders that require a co-signature. The pending prescriber co-signature name should default into the field from service, team, or coverage schedules, and there should be an option to override the name. The system should provide the ability to require that all orders be countersigned prior to placing a discharge order if the organization wishes to implement this.

Medication Order Status. Considerations regarding medication order status include the following:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree