The basis of many pressures that the industry faces from its critics results in part from the tension between the pharmaceutical industry being viewed both as a commercial for-profit business and also as a provider of drugs to help patients. Is this industry an essential part of the healthcare profession or is it a provider of drugs primarily to make money for its investors? The industry has not helped its position or image by sometime emphasizing one side of its Janus head to one group and another side to different groups. It has never decided to present itself solely as a profit making enterprise but wishes to benefit from being seen as a contributor to patient well-being. Many professionals inside the industry are clearly motivated by altruistic thoughts and goals, despite the orientation of the business in looking at the current and next quarter’s income.

United States Regulatory History

During the 19th century, the many problems of patent drugs and charlatans led to the need and eventual passage of laws in the United States to control vaccines (i.e., the 1813 Vaccine Act), imported drugs (i.e., the 1848 Import Drug Act), and adulterated and mislabeled drugs (i.e., the 1906 Pure Food and Drugs Act). These were followed by the well-known 1938 Food, Drug, and Cosmetic Act that focused primarily on ensuring that drugs were safe, and its 1962 Amendments (i.e., the Kefauver-Harris Amendments) that focused primarily on ensuring that drugs were effective.

Increasing regulatory standards are pressuring companies to discover highly profitable drugs to support their large research and development budgets. Other pressures (e.g., increasing competition among companies, stockholders, and cost-containment practices) are also contributing to this result. On the other hand, scientific advances are leading the industry to a position where they will eventually discover more drugs for smaller patient populations and this will raise the question of whether a new paradigm of drug discovery and development and marketing will have to be used (see

Chapter 16).

Many different groups are increasing their pressures on the industry to lower prices for older pharmaceuticals and to keep newer ones at relatively low prices. This is not a purely economic attack on prices; it is the tip of the political iceberg questioning whether a reasonable price for a pharmaceutical is based on free market economics (as exists for most industries) or is based on what the country can afford (i.e., more of a socialized healthcare concept).

Delays, unnecessary duplications, and inefficiencies in drug development plus inefficiencies in creating simultaneous regulatory submissions worldwide all create pressures on the industry to develop their drugs more rapidly and efficiently. Pressures from investors, analysts, and other financial professionals as well as price controls in some European and other countries create other pressures to charge high prices for their new drugs once they reach the market, even in highly competitive markets.

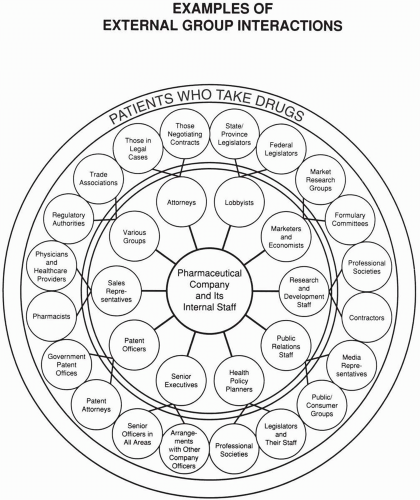

Pressures on the industry from external groups should elicit a broadly defined political response that is coordinated among many, if not most, companies. This response is often expressed through trade associations and by the company’s own lobbying efforts. In some cases, the companies act through independent organizations (e.g., think-tanks). Political attacks against companies should receive a political response, and economic issues and questions raised should receive an economic response. There are numerous occasions where the industry’s response to a political attack has been with an economic response (e.g., discussion of the high costs of research and development), which this author believes is overused and should be replaced with a message that is new and more targeted to addressing the concerns of industry’s critics.