Chapter Twenty-Two

Pharmaceutical Industry and Regulatory Agency Drug Information*

Learning Objectives

After completing this chapter, the reader will be able to

• Design an organization chart for a pharmaceutical company.

• Discuss opportunities for health care professionals (HPs) within the pharmaceutical industry.

• Describe how HPs are regulated in the pharmaceutical industry.

• Determine acceptable interactions between pharmaceutical companies and practitioners.

• List the components of a standard response and personalized letter.

• Explain the importance of collecting adverse event information.

• Identify pharmaceutical industry–associated organizations.

• Recommend methods for communicating safety information to consumers.

• Describe the role of the Division of Drug Information (DDI) at the Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

• List the main differences between the DDI and a typical drug information center.

• Illustrate the different types of drug information services provided by the FDA.

• Identify factors that guide selection of a specific FDA-sponsored resource or Web site.

• Discuss student and professional opportunities within the FDA.

![]()

Key Concepts

Introduction

There are many roles available to health care professionals (HPs) within the pharmaceutical industry and regulatory agencies focused on public health. In industry, these roles span medical education, publications, marketing, medical information, and more. In public health agencies, the roles are usually separate functions supporting the organizational mission statement and generally pertain to protecting the health of all Americans and providing essential human services, especially for those who are least able to help themselves. Job titles and descriptions may vary slightly from company to company or agency to agency, but the importance of HPs within each area is constant across organizations.

Throughout this chapter the reader will become familiar with the organization of a pharmaceutical company, professional mentoring relationships, industry’s regulated interactions with outside HPs, fulfillment of a medical information request and responses to unsolicited inquiries, the many roles and career paths available to HPs in industry, and the importance and requirements of adverse event reporting and postmarketing surveillance. Information surrounding the role of medical information within a regulatory agency, specifically the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), will then be presented. At the end, the reader should have a general knowledge of the roles and responsibilities of HPs employed in the pharmaceutical industry and FDA, the expectations practitioners receiving medical information from a pharmaceutical company or regulatory agency may have, and how to pursue opportunities and careers within the pharmaceutical industry or a regulatory agency with a public health mission.

Opportunities for Health Professionals Within Industry

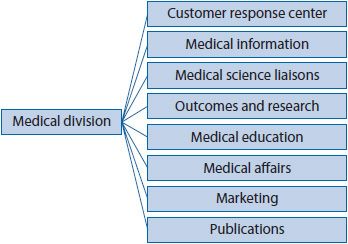

![]() Pharmaceutical companies’ scientific or medical divisions are staffed with highly trained HPs working in a multitude of specialized fields (see Figure 22–1).1 The following section will highlight specific opportunities within the pharmaceutical industry for HPs.

Pharmaceutical companies’ scientific or medical divisions are staffed with highly trained HPs working in a multitude of specialized fields (see Figure 22–1).1 The following section will highlight specific opportunities within the pharmaceutical industry for HPs.

Figure 22–1. Organization of pharmaceutical companies’ medical division.1

CUSTOMER RESPONSE CENTER

Customer response center representatives are the first-line response team for unsolicited requests* for medical information. HPs in this setting are well trained for customer response center representative positions. Customer response center HPs are faced with a variety of responsibilities as the first line of communication with patients and providers. Responsibilities include capturing adverse events (AEs) that are reported and triaging nonmedical and medical information requests (MIRs). Customer response center HPs are provided with a variety of tools, including, but not limited to, product labeling (or package inserts), response letters, question and answer (Q&A) documents, and clinical topic overviews, typically drafted by peers in the medical information division to assist in answering unsolicited requests for product information. A guidance document, published by the FDA, regarding responding to unsolicited requests, also offers industry the FDA’s current thinking on this topic.2 Customer response center staff use product labeling, response letters, and literature searches to assist them in responding to MIRs. HPs serving in this capacity must have excellent verbal communication skills and are highly trained in effectively searching for information. Some MIRs may require additional research or analysis resulting in the customer response center HPs escalating the inquiry to a medical information specialist for further investigation.

MEDICAL INFORMATION

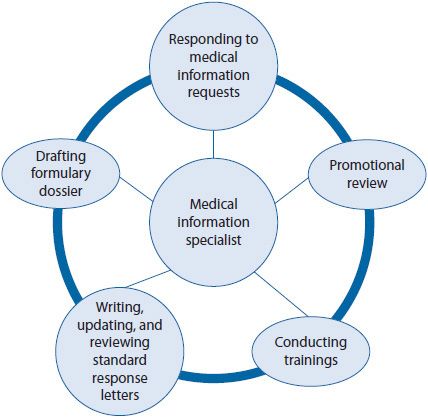

![]() Medical information specialists respond to inquiries, provide training, and draft materials for a variety of internal and external audiences. Medical information specialists are HPs who respond to unsolicited MIRs, write and update response letters, conduct scientific analysis of medical literature topics, review promotional materials, develop Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP)-formatted dossiers for formulary consideration, and train company staff (e.g., sales force, peers, account managers, and others [see Figure 22–2]).3,4

Medical information specialists respond to inquiries, provide training, and draft materials for a variety of internal and external audiences. Medical information specialists are HPs who respond to unsolicited MIRs, write and update response letters, conduct scientific analysis of medical literature topics, review promotional materials, develop Academy of Managed Care Pharmacy (AMCP)-formatted dossiers for formulary consideration, and train company staff (e.g., sales force, peers, account managers, and others [see Figure 22–2]).3,4

Figure 22–2. Responsibilities of medical information specialists.2

Medical information specialists also respond to MIRs that are escalated to them by customer response center representatives. Escalation, or the transfer of MIRs, occur frequently when the customer response center representatives do not have the resources necessary to formulate a response. Frequently, escalations involve questions about off-label use. This will be discussed later in the section entitled Regulation of Health Care Professionals in Industry. Medical information specialists may have access to additional resources, such as comprehensive reports from clinical trials, information provided to study investigators, marketing materials, posters and abstracts, and contacts in other departments, which makes them invaluable resources for analyzing and synthesizing information.

MEDICAL SCIENCE LIAISONS

Medical science liaisons (MSLs) originated as a highly specialized customer response center representative. An MSL supports, and is supported by, the scientific affairs and medical information team. MSLs have a close working relationship with key opinion leaders and are expected to engage in clinical conversations ranging from broad clinical guidelines to patient-specific care (Table 22–1).5 MSLs are expected to attend national meetings and provide comprehensive clinical presentations. MSLs may focus on one product or therapeutic area, so there may be overlapping MSLs working for the same company in one location, supporting different products and specialty areas, or vice versa, there may be one MSL in a remote location responsible for multiple products and therapeutic areas.

TABLE 22–1. RESPONSIBILITIES OF MEDICAL SCIENCE LIAISONS5

Responsibilities of medical science liaisons may include the following:

OUTCOMES RESEARCH

Outcomes research specialists are known in some companies as field-based outcomes liaisons or FBOLs. This position is similar to that of an MSL, except the focus of FBOLs may be to demonstrate the value of a product to managed care organizations, pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs), or other HPs in similar decision-making roles through the generation of outcomes data. Outcomes data typically provides studies focused on identifying, measuring, and evaluating the end result of a health care service or treatment. For example, a company that is marketing an antiplatelet medication might request that their FBOLs demonstrate to customers the value of the product through quality-life years gained or may request that the FBOLs create a risk stratification tool (e.g., stratification of risk for patients with cardiovascular disease) to assist clinicians in determining appropriate therapy options for their patients.

MEDICAL EDUCATION

HPs in medical education evaluate funding requests for continuing medical education (CME), continuing education (CE), and other programs submitted by qualified organizations. Grants are reviewed by medical education to ensure the program outlined in the grant addresses specific needs of clinicians in clinical practice and is consistent with the company’s educational goals and objectives for a specific therapeutic area.1 CME and CE programs must meet standards set by the corresponding accrediting body for the audience and should follow guidance documents published by the FDA.6,7

MEDICAL AFFAIRS

Medical affairs HPs typically oversee phase IV clinical trial programs and may also be involved with preclinical studies through phase IV or postmarketing studies. These HPs are primarily conducting research on marketed pharmaceuticals in areas of high therapeutic demands or information need. Medical affairs HPs play a key role in shaping the direction of future clinical development including where to focus resources on specific disease states, what drug candidates to support in human clinical studies, and what marketed drugs to develop with new indications or to study through the investigator-initiated study process. In addition, medical affairs staff is involved in a variety of tasks with peers in medical information, marketing, and with key opinion leaders in the field. These tasks include reviewing promotional and marketing materials, supporting phase IV clinical trial sites and maintaining communication with trial investigators, reviewing product labeling, formulary dossiers, training materials for promotional and education purposes, and developing and presenting original research in the form of posters, abstracts, and manuscripts. Medical affairs HPs are responsible for reviewing these materials for accuracy of medical information and to ensure that the final products (e.g., promotional materials, package inserts) are unbiased, fair balanced, and not misleading.1

MARKETING

HPs in the marketing division of a pharmaceutical company are responsible for developing the branded messages for a product. See Chapter 23 for further information on pharmaceutical marketing. The tag lines and main selling points seen in journal advertisements, on Web pages, and on printed materials are created by the marketing division. It is important for HPs in marketing to understand the clinical practice environment of their peers so they can provide useful, valuable tools and materials. Marketing drafts a plethora of promotional materials from journal and television advertisements to functional educational tools such as dose conversion guides. All of these materials are then reviewed by peers in medical information and medical affairs, and other internal business partners in regulatory and legal.1

PUBLICATIONS

The team of HPs in the publications department has the important task of ensuring the appropriate information reaches the appropriate audience. For example, a company coming to market with a new blood pressure medication would want its publications department to create a plan that would publish trial data (preclinical through post hoc and review data) concurrently with major meetings of prescribers treating blood pressure. The publications department ensures that reprints of posters, abstracts, and manuscripts are readily available for dissemination to HPs in the field. HPs in this department are also responsible for reviewing the final content of publications and drafting comments if necessary, often through a partnered review process with medical affairs and medical information, to make certain accurate information is available for practitioners in clinical practice.1

As outlined in this section, HPs have many varied opportunities within the industry. Each of the functions described previously abide by a set of rules and regulations. Understanding and complying with these rules and regulations help ensure the success of industry-employed HPs.

Regulation of Health Care Professionals in Industry

![]() Pharmaceutical companies are regulated both externally by the FDA and internally by standard operating procedures (SOPs).8,9 To help internal staff understand the regulations governing their department’s duties and establish an efficient methodological approach to the business, SOPs are developed internally by the company.2,3 While practitioners in clinical practice may not be governed by the same regulations as industry, having a basic understanding of company’s regulations will help align the external clinicians’ expectations with what can be provided by internal industry HPs.

Pharmaceutical companies are regulated both externally by the FDA and internally by standard operating procedures (SOPs).8,9 To help internal staff understand the regulations governing their department’s duties and establish an efficient methodological approach to the business, SOPs are developed internally by the company.2,3 While practitioners in clinical practice may not be governed by the same regulations as industry, having a basic understanding of company’s regulations will help align the external clinicians’ expectations with what can be provided by internal industry HPs.

CODE OF FEDERAL REGULATIONS

The Code of Federal Regulations (CFR) Title 21 regulates the United States (U.S.) pharmaceutical industry throughout the life cycle of a product, from before the investigational new drug application (pre-IND) through phase IV clinical trials, including postmarketing data collection.6,7,10–14 HPs working for a U.S. pharmaceutical company must achieve a thorough understanding of these regulations to ensure compliance with the regulations that pertain to their daily duties.

FDA GUIDANCE DOCUMENTS

FDA guidance documents represent the FDA’s current thinking on a topic. Guidance documents do not create or confer any rights for or on any person and do not operate to bind the FDA or public. Guidance documents are very useful because they expand upon the regulations. ![]() The FDA’s draft Guidance for Industry, “Responding to Unsolicited Requests for Off-Label Information About Prescription Drugs and Medical Devices,” describes the FDA’s current thinking about how manufacturers and distributors of prescription human drug products can respond to unsolicited requests for information about unapproved indications (off-label information) related to their FDA-approved or cleared products. An important portion of this guidance document for pharmaceutical companies is the discussion of unsolicited requests that are encountered through emerging electronic media. First though, several important definitions are provided with examples.

The FDA’s draft Guidance for Industry, “Responding to Unsolicited Requests for Off-Label Information About Prescription Drugs and Medical Devices,” describes the FDA’s current thinking about how manufacturers and distributors of prescription human drug products can respond to unsolicited requests for information about unapproved indications (off-label information) related to their FDA-approved or cleared products. An important portion of this guidance document for pharmaceutical companies is the discussion of unsolicited requests that are encountered through emerging electronic media. First though, several important definitions are provided with examples.

UNSOLICITED REQUESTS

![]() Unsolicited requestsare those initiated by persons or entities that are completely independent of the relevant firm. (This may include many HPs, health care organizations, members of the academic community, and formulary committees, as well as consumers such as patients and caregivers.) Requests that are prompted in any way by a manufacturer or its representatives are not unsolicited requests.

Unsolicited requestsare those initiated by persons or entities that are completely independent of the relevant firm. (This may include many HPs, health care organizations, members of the academic community, and formulary committees, as well as consumers such as patients and caregivers.) Requests that are prompted in any way by a manufacturer or its representatives are not unsolicited requests.

Two Types of Unsolicited Requests

Nonpublic unsolicited requests

A nonpublic unsolicited request is an unsolicited request that is directed privately to a firm using a one-on-one communication approach. For example: An individual calls or e-mails the medical information staff at a firm seeking information about an off-label use. In this case, neither the request nor the response would be visible to the public.

Public unsolicited requests

A public unsolicited request is an unsolicited request made in a public form, whether directed to a firm specifically or to a forum at large. For example: During a live presentation, an individual asks a question, directed to a firm’s representative but heard by other attendees, regarding off-label use of a specific product. This request is a public request. Similarly, a response by the firm that is conveyed to the same audience as the original question would be considered a public response. Another example is if an individual posts a question about off-label use of a specific product on a firm-controlled Web site (or a third-party discussion forum), that is visible to a broad audience. The request could be directed to a firm specifically or posed to users of a discussion forum at large. This request is a public online request. Similarly, a response by the firm that is visible to the same audience as the original question would be considered a public online response.

SOLICITED REQUESTS

![]() The FDA considers requests for off-label information that are prompted in any way by a manufacturer or its representatives to be solicited. Such solicited requests may be considered evidence of a firm’s intent that a drug be used for a use other than that specifically approved by the FDA. For example, if a firm announces results of a study via a microblogging service (e.g., Twitter) and suggests that an off-label use of its product is safe and effective, any comments and requests received as a result of the original message about the off-label use would be considered solicited requests.

The FDA considers requests for off-label information that are prompted in any way by a manufacturer or its representatives to be solicited. Such solicited requests may be considered evidence of a firm’s intent that a drug be used for a use other than that specifically approved by the FDA. For example, if a firm announces results of a study via a microblogging service (e.g., Twitter) and suggests that an off-label use of its product is safe and effective, any comments and requests received as a result of the original message about the off-label use would be considered solicited requests.

The FDA has long taken the position that firms can respond to unsolicited requests for information about FDA-regulated medical products by providing truthful, balanced, nonmisleading, and nonpromotional scientific or medical information that is responsive to the specific request, even if responding to the request requires a firm to provide information on unapproved indications or conditions of use.

STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURES

SOPs provide additional guidance to employees, supplementing regulations from federal and state government agencies. SOPs allow a company to digest federal regulations, making them applicable to employees and their everyday job functions.15 The pharmaceutical industry employs HPs and lawyers in regulatory affairs to ensure SOPs are up-to-date and provide employees proper guidance for complying with all applicable regulations.

Case Study 22–1

![]() DRUG A®

DRUG A®

The pharmaceutical company, Awesome Drug R Us, Inc., is planning to file a new drug application (NDA) for DRUG A®, their new medication to treat moderate to severe hiccups. Awesome Drugs R Us, Inc., is a small start-up company and has never launched a marketed product prior to DRUG A®. The company currently employs a small number of HPs in medical affairs and marketing. Awesome Drug R Us, Inc., received a priority review (a drug product with priority review designation is one where the FDA’s goal is to take action on the application within six months, rather than 10 months in a standard review, although it is not a requirement to do so) for DRUG A® and is expecting a review action in 6 months following the NDA filing.

• What internal documents should Awesome Drugs R Us, Inc., prepare so their employees are aware of the regulations governing their job functions?

• What external regulations should Awesome Drugs R Us, Inc., include in education for their staff?

• Discuss the job responsibilities in the current departments at Awesome Drugs R Us, Inc.

• What are some other departments Awesome Drugs R Us, Inc., should consider developing in the future? What are some of the job responsibilities of these departments?

![]()

Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America and the Code on Interactions with Health Care Professionals

HPs within the pharmaceutical industry hold themselves to a high standard when it comes to providing accurate, concise, and timely information. ![]() Interactions between pharmaceutical companies and HPs are defined, but not regulated, by a code of conduct established by Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) through the revised version of the Code on Interactions with Health Care Professionals.16 The prior edition, from 2002, addressed primarily products being marketed and activities prior to the launch of a medication. The updated version released in January 2009 includes more specific guidance regarding the interactions between pharmaceutical industry representatives and HPs. The goal of these regulations is to provide transparency to HPs and patients alike as to the motives and channels through which industry conducts business with external customers and business partners.17

Interactions between pharmaceutical companies and HPs are defined, but not regulated, by a code of conduct established by Pharmaceutical Research and Manufacturers of America (PhRMA) through the revised version of the Code on Interactions with Health Care Professionals.16 The prior edition, from 2002, addressed primarily products being marketed and activities prior to the launch of a medication. The updated version released in January 2009 includes more specific guidance regarding the interactions between pharmaceutical industry representatives and HPs. The goal of these regulations is to provide transparency to HPs and patients alike as to the motives and channels through which industry conducts business with external customers and business partners.17

Case Study 22–2

Use information from Case Study 22–1.

• What department(s) would review grants for educational programming for DRUG A®?

• What department(s) may be involved in approving marketing materials for DRUG A®?

![]()

Fulfillment of Medical Information Requests

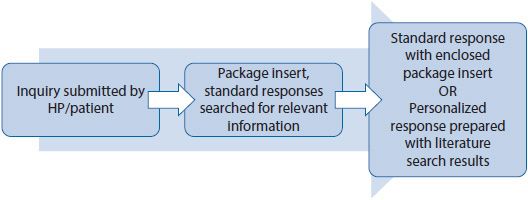

HPs and patients may contact a pharmaceutical company with questions regarding a medication when an answer is not readily available. A typical process for responding to these questions is described in Figure 22–3.

Figure 22–3. Medical information request receipt and fulfillment process.

RESPONSE LETTERS

![]() Clinical response lettersare written correspondence in response to unsolicited requests for medical information. The use of evidence-based medicine in response letters allows consumers and HPs to be confident they are receiving fair-balanced, unbiased, and not misleading information.18 Response letters are usually created according to a template for consistency (see Table 22–2) and drafted in anticipation of, or in response to, frequently asked questions.10 Solvay Pharmaceuticals determined that prior to the launch of a product, response letters took four to 8 hours each to create. The time spent by Solvay’s staff to create a response letter following launch significantly increased, taking 4 to 7 days to create. This was directly related to the increased workload and the continuous arrival of new MIRs.19 Once a product is available on the market, the number and complexity of MIRs is likely to increase. This increases HP’s total workload and, therefore, increases the time it takes to complete individual tasks, such as creating response letters. Because of this, the time to create a response letter and respond to an MIR may differ from Solvay’s results.

Clinical response lettersare written correspondence in response to unsolicited requests for medical information. The use of evidence-based medicine in response letters allows consumers and HPs to be confident they are receiving fair-balanced, unbiased, and not misleading information.18 Response letters are usually created according to a template for consistency (see Table 22–2) and drafted in anticipation of, or in response to, frequently asked questions.10 Solvay Pharmaceuticals determined that prior to the launch of a product, response letters took four to 8 hours each to create. The time spent by Solvay’s staff to create a response letter following launch significantly increased, taking 4 to 7 days to create. This was directly related to the increased workload and the continuous arrival of new MIRs.19 Once a product is available on the market, the number and complexity of MIRs is likely to increase. This increases HP’s total workload and, therefore, increases the time it takes to complete individual tasks, such as creating response letters. Because of this, the time to create a response letter and respond to an MIR may differ from Solvay’s results.

TABLE 22–2. COMPONENTS OF A STANDARD RESPONSE LETTER21

Pharmaceutical companies’ response letters are created from source documents in response to frequently asked questions and are peer reviewed internally.20 Standard response letters developed by companies may be either proactive or reactive. For example, if the evening news reports that a marketed drug, similar to Drug A® causes yellow stripes to appear on patients’ skin, the company that makes the competitor to Drug A®

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree