Pharma-think, Academic-think, and Government-think

Research is to see what everybody else has seen, and to think what nobody else has thought.

–Albert Szent-Gyorgyi

One of the signs of an approaching nervous breakdown is the belief that one’s work is terribly important.

–Bertrand Russell

Professionals who join the pharmaceutical industry from academia, government, other industries, or medical practice quickly see that the nature of pharmaceutical thinking differs in major ways from their previous way of thinking. In order to be fully effective both with in-house colleagues and with outsiders, these professionals must acquire and master pharma-think. Fortunately, most professionals can learn pharma-think without too much difficulty. The unfortunate fact is that few companies attempt to systematically train new staff in this area. Many people have to learn pharma-think entirely on their own, a process that may take a few years. Ironically, it is newly hired junior level staff more than senior managers and executives who are encouraged by their companies to take in-house courses and to attend basic courses outside the company that teach about pharma-think.

Industry managers and executives assume that new professionals they hire from academia and government understand the nature of the pharmaceutical industry and can operate effectively without specific training in the area of how pharma sense and pharma-think differ from that of their previous position. They believe that such new professionals only need to be taught the basic elements of their position. One of the primary messages of this chapter is to challenge that assumption and state that education of all new professionals, particularly those from academia and government service, should include lectures and material on how they can develop pharma sense and pharma-think.

This chapter describes several types of “think” frequently encountered by industry professionals. The basic differences among pharma-think, academic-think, and government-think relate to incentives, motivations, and specific pressures that influence them. These differences usually lead professionals in these areas to have different perspectives when they approach a problem and often to reach different conclusions about the same issue or question. Other work environments (e.g., consulting, full-time medical practice) also have their own characteristics but are not discussed in this chapter.

PHARMA SENSE AND PHARMA-THINK

Why Do Some Professional Staff Never Fit in the Pharmaceutical Industry?

The author has often wondered why some professionals who enter a pharmaceutical company for the first time adapt very rapidly to their new position, the company, and the industry, whereas others never seem to fit. It certainly has nothing to do with intelligence, training, prior experience in another industry, or prior interactions with industry professionals. Some professionals lose their desire to learn new skills and to fit into a new environment after leaving school. While this change may play a small role for some people, a more important factor is personality.

A desirable personality trait can be described as flexibility. This trait is present in everyone to a different degree. It is not the sole reason why some people fit in well in the pharmaceutical industry, but it plays an important role, as does the strength of a person’s desire to fit into the company.

The person who fits in rapidly (and well) within a pharmaceutical company enjoys working in groups and sees the company’s goals as ones that he or she can endorse and work toward achieving. This professional is interested in learning pharmaceutical industry principles and perspectives and does not simply assume or believe that it is like his or her previous environment. These persons seek to learn pharma sense from their experiences and from their mentors, as well as from courses and readings.

How People Inside the Industry Obtain Pharma Sense and Pharma-think

People in the pharmaceutical industry do not have an opportunity to become well versed in the detailed operations of the many widely dispersed disciplines that play a major role in the industry (e.g., basic research, clinical research, finance, law, manufacturing, marketing). However, the individual elements of the entire universe of pharmaceutical disciplines do not need to be mastered to have a well-developed pharma sense and to be able to use pharma-think.

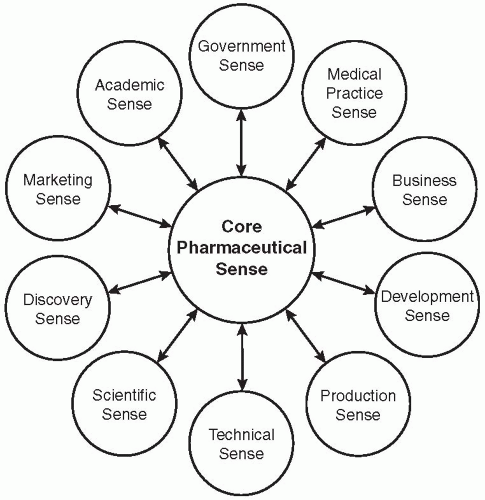

The first principle to conceptualizing what pharma sense and pharma-think mean is to recognize that they exist within each function in the industry and that they require an understanding of how the pharmaceutical company and even industry is organized and functions. A person may become highly sophisticated within any one area and develop a great deal of pharma sense that relates to that discipline (Fig. 5.1). From that knowledge, he or she may then develop a general (or core) pharma sense about the industry and possibly further develop pharma sense in other disciplines.

It is also possible to develop a greater and greater degree of pharma sense by progressively moving from one’s core discipline, which has been mastered, to others that are directly related and eventually to those that are more indirectly related. Figure 5.1 presents the view that, while many of these categories overlap with some others to a degree, there is still a distinction between such categories as discovery sense and development sense, preclinical sense and discovery (or development) sense, and many others. Scientific sense is a far more general term and meant to be differentiated from medical practice sense, in that few physicians possess scientific sense. Scientific sense has several subtypes, such as preclinical sense and clinical sense, when it refers to the science of clinical medicine.

It is only logical that each person’s own discipline is the most important to master. But since no discipline exists without major influences from others and on others, each professional should develop as much pharma sense as possible about the areas that are directly related to his or her own areas and with which he or she interacts.

Learning about other functions and disciplines contributes to the knowledge, experience, and pharma sense developed in one’s own area of expertise. For example, a marketing manager must learn a great deal about how production issues affect his or her area of marketing and also about how research and development, law, finance, and other disciplines affect the area. A marketing manager must also learn how other areas of marketing affect his or her area of marketing. Ironically, some marketing areas (e.g., over-the-counter drug promotion) may not be as close to the central activities and knowledge in marketing (e.g., prescription market research) as certain nonmarketing disciplines (e.g., finance, production).

The more senior the pharmaceutical manager, the more he or she should understand pharma sense in many (if not most) of the disciplines with which he or she interacts. The ideal company president will have an excellent understanding of what makes pharma sense in production, marketing, research, and most other areas as well. If this individual lacks this knowledge, then he or she must have trusted heads of each of those areas who can provide the most sophisticated decision-making skills in the company and who are entrusted to make appropriate decisions within their disciplines. It is common within both large and small pharmaceutical companies to find company presidents without broad knowledge, experience, and well-developed pharma sense. Instead, company presidents are usually successful attorneys, financial experts, marketers, or others with good business sense. While these skills are important attributes, they are insufficient on their own to make many major corporate decisions.

How to Best Learn the Operations of Multiple Functions

To learn about how a company and each of the internal functions operate, the best approach is to work in multiple areas inside the company, observe the methods that work, and learn about how things are done. It is important to learn which approaches succeed or fail and why. Few people within the pharmaceutical (or any other) industry have a goal of learning how the entire organization works. Of course, almost everyone wants to learn how to do his or her specific job well and how his or her small group and section operate, but fewer people in a large company try to understand how their department and division interact with others and how company goals influence and interact at each level of the organization.

What Is the Difference between the Pharma Sense of a Novice and Expert?

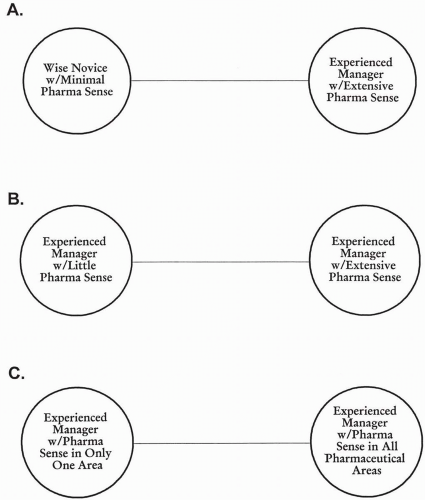

Figure 5.2 shows three spectra with which to consider some aspects of pharma sense. In Fig. 5.2A, the major difference between a wise novice and an experienced manager with extensive pharma sense is primarily the number and types of experiences of the more experienced manager. The tools they use to learn important lessons and general approaches are essentially the same.

In Fig. 5.2B, the major difference between the two managers is that one is actively learning from his or her experiences and is better able to do so than the other. Thus, one person will benefit more than the other from their own experiences, those of their company, and those of the industry.

The managers described in Fig. 5.2C differ in attitude and inquisitiveness, and although one can have pharma sense limited to a narrow area, it is hoped that that individual will not be promoted very high within the organization. The more senior the manager, the more pharma sense he or she should have across multiple pharmaceutical areas. A classic and all too common error in this regard is when a great scientist is promoted to be a manager but lacks the skills and even the pharma sense of how to be an effective manager in his or her company.

Obtaining a Pharmaceutical Perspective on a Drug or on an Issue

Most professionals are trained in their specialty to focus on the details of their particular area. Few are trained to view the entire scope of issues or projects that are being worked on in their own functional area (e.g., production, marketing, research and development). Even fewer professionals are trained (or even become experienced) in viewing functional areas outside their own (e.g., a production manager developing an understanding of marketing and being able to develop and use a marketing perspective).

How to Understand Other People’s Perspectives

Because of their scope of training or experience, many people have limitations in understanding other people’s perspectives. It is nonetheless possible to view current and future goals of one’s position (or the roles of others) in such a way as to broaden one’s vision. This may be accomplished by having meetings with colleagues or mentors and by attending relevant conferences or professional meetings where this is discussed. Another technique is to read trade journals, magazines, and newsletters in addition to respected national newspapers that present such stories. A final method is to read textbooks that describe the overall activities of a company, drug development, and other functions within a company.

A broad perspective may often be achieved by viewing all drug development (or marketing, discovery, production, etc.) using multiple approaches (e.g., consider different customers and groups, different phases of a study, different functions). The same comments apply to evaluating an entire therapeutic area, disease, or other category. The broad perspective is not always the best approach to understand or to operate within one’s job, but it should be considered before one adopts the narrower perspectives that are more commonly used within one’s discipline.

A professional who uses a broad perspective might ask the following question: “We’re considering developing a drug for indication X, but another disease it could work in is Y. We could get the drug to market faster by developing it for Y, but Y is a smaller market than X, and sales would probably be less. Which disease should we focus on initially, since we do not have the resources to do both simultaneously?” The same type of question could apply to two or more dosage forms of the same drug.

It is likely that numerous pictures can be described for any issue. As a result, one must evaluate whether one’s own picture is the most correct or whether another would include more

and/or different facts in correct perspective. This test of one’s perspective can be evaluated by oneself and can be finely tuned by discussing it with one’s mentor, colleagues, or experts in the field.

and/or different facts in correct perspective. This test of one’s perspective can be evaluated by oneself and can be finely tuned by discussing it with one’s mentor, colleagues, or experts in the field.

How People External to the Pharmaceutical Industry Can Learn Pharma Sense

Only a very small number of outsiders are able to understand the workings and behavior of a single pharmaceutical company and the myriad of functions and issues that transpire at this level. At the level of a single drug, many outsiders are also able to understand the issues involved in drug discovery, development, production, and marketing. In many ways, focusing on the issues regarding a single drug is easier to understand than understanding how a company operates. It is somewhat common for outsiders to “know” or learn how a single drug was developed but, at the same time, have absolutely no comprehensive understanding of the drug development process. When some of these people have written articles or books, it has led to many issues and misunderstandings of the industry’s fundamental procedures, strategies and approaches.

Some industry outsiders such as journalists learn a great deal about the overall pharmaceutical industry by interviewing various experts. Their newspaper stories, magazine articles, or even books are often extremely perceptive and accurate. Other approaches for outsiders to learn about the industry level are to focus on national and international economic, marketing, medical, scientific, and political issues.

Situations Where Pharma Sense and Pharma-think Are Necessary

There are a myriad of situations in the pharmaceutical industry where a strong ability to use pharma sense and phama-think are helpful or essential. An overview of the relationship of pharma sense and pharma-think and how it leads to pharma action is shown in Fig. 5.3. An individual with pharma sense and an ability to use pharma-think should be able to determine the following:

How to approach a novel pharmaceutical problem or issue where no precedent can be uncovered

How to stick with a strategy that has been thoroughly discussed and accepted, and not be swayed by those who propose new approaches that do not survive careful scrutiny

When to switch from a strategy that is not working

What new ideas are merely examples of a current fashion that are unproven and likely to disappear in a short period, and what new ideas represent major innovations

How and when to choose consultants to help the company

When to walk away from negotiations and drop a potential deal that is overpriced or has unacceptable terms that cannot be negotiated successfully

What questions are the most appropriate ones to ask and in what order they should be addressed

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree