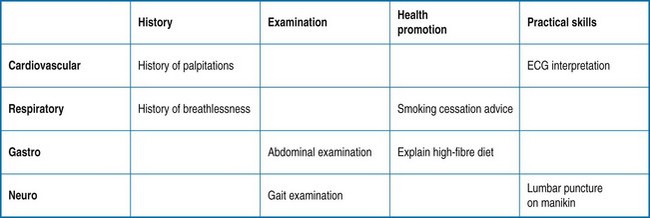

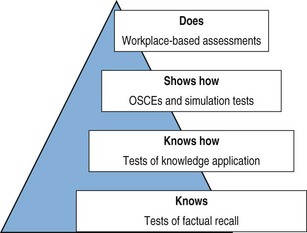

Chapter 38 The terms performance and competence are often used interchangeably. However, competence should describe what an individual is able to do, while performance should describe what an individual actually does in clinical practice. Clinical competence is the term being used most frequently by many of the professional regulatory bodies and in the educational literature. There are several dimensions to competence, and a wide range of well-validated assessments have been developed examining these. Traditional methods focus on the assessment of competence in artificial settings built to resemble the clinical environment. However, more novel methods of performance assessment concentrate on building up a structured picture of how the individual practitioner acts in his or her everyday working life, in interactions with patients and other practitioners, using technical, professional and interpersonal skills. Miller’s model, shown in Fig. 38.1, provides a framework for understanding the different facets of clinical competence and the assessment methods that test these. Fig. 38.1 Miller’s model of competence (adapted from Miller: Academic Medicine 65(suppl):S63–S67, 1990.). When planning assessments, it is important to be aware of the purpose of the assessment and where it fits into the wider educational programme: a tool is only as useful as the system within which it resides. Considerations would include how to make pass/fail decisions, how to give feedback to candidates, effects on the learning of candidates and whether the assessment is ‘high-stakes’. For example, assessments for the purpose of certification may require different criteria than some medical school assessments, where the primary purpose is to encourage and direct the learning of students (Downing 2003). In considering the best tools for the purpose of a particular assessment system, educators need to evaluate their validity, reliability, educational impact and acceptability (Schurwith & van der Vleuten 2009). • Demonstrating that the content of the assessment relates meaningfully to the learning outcomes • Demonstrating that the quality of the items has been rigorously appraised • Demonstrating that the results (scores) accurately reflect the candidates’ performance • Demonstrating that the statistical (psychometric) properties of the assessment are acceptable. This includes the reproducibility of the assessment, as well as item analyses (such as the difficulty of each item and the discrimination index). How is it used? The OSCE is typically used in high-stakes summative assessments at both the undergraduate and postgraduate level. The main advantages are that large numbers of candidates can be assessed in the same way across a range of clinical skills. High levels of reliability and validity can be achieved in the OSCE due to four main features (Newble 2004): • Structured marking schedules, which allow for more consistent scoring by assessors • Multiple independent observations collected by different assessors at different stations, so individual assessor bias is lessened • Wider sampling across different cases and skills, resulting in a more reliable picture of overall competence • Completion of a large number of stations, allowing the assessment to become more generalizable Organization: OSCEs can be complex to organize. Planning should begin well in advance of the examination date, and it is essential to ensure that there are enough patients, simulated patients, examiners, staff, refreshments and equipment to run the complete circuit for all candidates on the day of the exam. Careful calculations of the numbers of candidates, the length of each complete circuit and how many circuits have to be run need to be made. The mix of stations is chosen in advance and depends on the curriculum and the purpose of the assessment. A blueprint should be drawn up which outlines how the assessment is going to meet its goals. An example of a simple blueprint, detailing the different areas of a curriculum and how the stations chosen will cover these, can be seen in Fig. 38.2. Development of a blueprint ensures adequate content validity, the level to which the sampling of skills in the OSCE matches the learning objectives of the whole curriculum. It is also necessary to think about the timing of the stations. The length of the station should fit the task requested as closely as possible. Ideally, stations should be practised in advance to clarify this and anticipate potential problems with the setup or the mark sheet. Thought also has to be given to the training of assessors and standardized or simulated patients.

Performance and workplace assessment

Introduction

Choosing the right assessment

Assessments of clinical competence

Objective structured clinical examination (OSCE)

Performance and workplace assessment