Ellen K. Murphy

Patient Safety and Risk Management

Think about what happens in the perioperative setting. Patients’ natural pain, communication, and reflex and infection defenses are purposefully diminished or obliterated. Their bodies are positioned on very firm flat surfaces and in unnatural positions. Then their bodies are further traumatized with instruments, fibers, drugs, and other foreign materials. It is no wonder that more than one quarter of the reported sentinel events from 2006 through 2012 occurred in the perioperative setting (Table 2-1).

TABLE 2-1

Summary Data of Perioperative Sentinel Events Reviewed by The Joint Commission

| Type of Sentinel Event | Number of Events from 2004 to 2012 |

| Anesthesia-related event | 94 |

| Fall | 538 |

| Fire | 98 |

| Infection-related event | 153 |

| Med equipment-related | 193 |

| Medication error | 378 |

| Op/postop complication | 719 |

| Transfusion error | 114 |

| Unintended retention of a foreign body* | 773 |

| Wrong-patient, wrong-site, wrong-procedure | 928 |

| All others† | 3006 |

| Total Incidents Reviewed | 6994 |

†Examples include criminal event, infant abduction, suicide, and perinatal death/injury.

Modified from www.jointcommission.org/assets/1/18/2004_4Q_2012_SE_Stats_Summary.pdf. Accessed February 11, 2013.

Although patient safety should be, and is, a paramount concern to nurses in all settings, nowhere is it more imperative than in the immediate perioperative period. Additionally, many elements of perioperative patient safety are coextensive with those of workplace safety (see Chapter 3).

This chapter describes the evolution of perioperative patient safety and the management of injury risks as a collective responsibility of the entire healthcare team.

History

Patient safety remains a primary concern for members of the surgical team. Primum non nocere or “First, do no harm,” is a long-standing imperative for physicians and nurses. Early operating room (OR) nursing textbooks written by OR nurses included counting sponges among nursing duties (e.g., Smith, 1924). Perioperative nursing textbooks and curricula continued to include substantial content on infection control, positioning, safe medication practices, and counts through World War II. The first edition of this very textbook by Edythe Alexander (1943) included content on asepsis, the importance of correct side surgery, proper blood handling, and proper tourniquet application. Alexander did not use the word “safety,” but she described the purpose of “perfecting every detail . . . to insure that patients . . . have every chance to overcome the disease or injury with which they are afflicted” (1943, p. 7).

After World War II, safety activities increased and became more formalized. The Joint Commission for the Accreditation of Hospitals (JCAH), now The Joint Commission, emerged. Nursing groups and publications increasingly emphasized their patient safety content. The American Nurses Association (ANA) published its Code for Nurses, which included provisions on patient safety and privacy, and the Association of Operating Room Nurses (now, the Association of periOperative Registered Nurses [AORN]) organized in the early 1950s. From the beginning, AORN’s conferences and publications were replete with patient safety information. Its first conference in 1954 included programs on methods improvement, explosion prevention, bacteria destruction, the surgeon-nurse relationship, and positioning (Glass and Murphy, 2002). AORN published its first Standards of Operating Room Practice in 1974. Its Technical Standards soon followed, and by the 1980s it published and regularly updated its Recommended Practices (RPs). AORN soon became and remains the primary resource and a fundamental authority for evidence-based perioperative safety practices (e.g., the RP on sterile technique [AORN, 2013]).

Safety as an Individual Responsibility

Throughout the 1980s, healthcare authorities viewed professionals’ errors and their effects on patient safety primarily as the individual practitioner’s responsibility. The legal and professional licensure systems tended to reinforce this approach. Any finding of negligence required that at least one individual had failed to do what a similarly situated, reasonable, and prudent professional would have done under similar circumstances. Likewise, professional licensure related to the abilities and behavior of the individual licensee.

In 1991, Brennan, Leape, and others proposed that despite individual best efforts by professionals, mistakes continued and were, in fact, more common than previously thought (Brennan et al, 1991). Their findings, combined with James Reason’s influential book Human Error (1990), spawned a plethora of new safety-related groups (Box 2-1), as well as fresh research and literature based on the role of systems, human factors, and their relationship to human error in healthcare. Researchers and authorities began to recognize human errors leading to patient injuries not so much as an individual’s shortcoming, deserving of blame or punishment, but more as a result of system failures in patient care areas such as the perioperative setting. Similarly, Leape (1994), Cook and Woods (1994), and others urged that the legal and professional licensure systems’ continued focus on individual error was misplaced if adverse patient events were to be effectively prevented. They urged an emphasis on transparent systems that required open reporting, investigation, innovation, and dissemination. The aviation and nuclear systems’ parallel examination of human factors served as models for ideas that led to relative success in preventing injury attributable to human error. Communication and teamwork have been identified as key factors to promote patient safety.

In the first edition of this textbook, Alexander noted that “to get the best result from a surgical operation, the surgeon and his assistants, the operating room nurse and the entire staff must work as a team” (1943, p. 8). Despite AORN and its partner professional associations’ emphasis on safety and teamwork, however, patient injuries caused by human error in perioperative settings continue (Pronovost and Colantuoni, 2009; TJC, 2012b).

Concentrated Emphasis on Systems

This earlier work took on urgency in 1999. The Institute of Medicine (IOM) landmark work, To Err Is Human, spurred major additional safety initiatives when it reported that at least 44,000, and perhaps as many as 98,000, patients died in U.S. hospitals every year as a result of preventable adverse events (IOM, 1999). Even the lower figure exceeded the number of deaths resulting from motor vehicle accidents, breast cancer, or acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS). The IOM report did not focus solely on perioperative errors. However, it did refer to Reason’s (1990) theory that complex, tightly coupled systems are most prone to accidents, and specified the surgical suite, along with emergency departments and intensive care units, as examples of complex, tightly coupled systems. Moreover, when one considers the incredibly complex highly invasive surgical procedures and number of team members and disciplines involved, juxtaposed with anesthetized patients who are unable to detect pain or otherwise defend themselves, patient vulnerability and the consequent need for protection by all team members are strikingly apparent. More than 4000 surgical “never events” occurred each year between 1990 and 2010 in the United States, according to the findings of a retrospective study of national malpractice data (Johns Hopkins Malpractice Study, 2012).

Brennan and colleagues (1991) studied 30,121 randomly selected hospital records, found adverse events occurred in 3.7% of hospitalizations, and concluded that substandard care had caused substantial numbers of patient injuries. In part 2 of that study, Leape and colleagues (1991) found that nearly half (48%) of adverse events were associated with surgery. Their results were consistent with those of earlier investigators, who had found half of all hospital-based, potentially compensable events (i.e., injuries from substandard care) arose from treatment in the OR. The Joint Commission (TJC) findings from 2006 to 2012 (TJC, 2012b) are similarly consistent with those findings: Individual efforts of the best nurses, surgeons, and anesthesia providers, combined with a recognized need for teamwork, are not sufficient to prevent injury— and are especially insufficient in the perioperative setting.

This shift away from emphasis on individual responsibility to a broader systems approach that began in the 1990s has accelerated since 2000. Advances in surgical instrumentation and health information systems, as well as in social media and consumerism, have combined to alter the context of perioperative care dramatically. This change in context requires a new and more inclusive, global approach to safety.

New terms and phrases have joined the patient safety lexicon, such as “e-iatrogenesis,” “better systems for patient safety,” “shared decision making,” and C. diff. Checklists and tools for measuring safety practices have multiplied (e.g., the Institute for Healthcare Improvement (IHI) Global Trigger Tool for Measuring Adverse Events, Partnerships for Patients and IHI Improvement Blogs; the National Quality Forum’s (NQF) Safe Practices Quality Positioning System; and National Priorities Partnerships to the Leapfrog Group’s Health User Group Dashboards). Safety scholars have published influential treatises for the professions and the public that have raised everyone’s awareness of checklist initiatives (e.g., Conley, 2011; Gawande, 2009).

Despite the impressive initial effectiveness of checklists (Haynes et al, 2009), barriers to their adoption (Fourcade et al, 2012) and a parallel need for flexibility, leadership, and teamwork different from current practice (Walker, 2012) have been identified. Various voluntary and governmental standards have so proliferated that matrices are published by still other groups to compare or provide crosswalks between them.

Major Association Safety Activities

TJC and TJC International, especially their National Patient Safety Goals (NPSGs), are excellent sources for safety information applicable to systems and facilities wherein invasive procedures take place. The AORN Perioperative Standards and Recommended Practices is the best source for information specific to perioperative nursing practices. Major government agencies that provide financial incentives and research resources for patient safety are also useful sources for safety information for facilities and individual professionals.

The Joint Commission

TJC has long been involved with quality and safety. It sharpened its systems-based safety focus in the mid-1990s when it established its Sentinel Event Policy. That policy first encouraged and then required self-reporting of medical errors and root cause analyses of them. Based on cumulative data, TJC published its first NPSGs in 2003. It then recognized the need for standardized methods of patient identification and established the Universal Protocol (discussed later in this chapter) in 2004. By 2005, the World Health Organization (WHO) formed the Collaborative Centre for Patient Safety Solutions, comprised of TJC and TJC International. TJC also is a founding member of the National Patient Safety Foundation (NPSF), collaborates with the National Quality Forum (NQF), and is an affiliate of Consumers Advancing Patient Safety (CAPS).

Sentinel Events.

TJC designated unexpected occurrences involving death or risk of serious physical or psychologic injuries as sentinel events. It chose the word “sentinel” to indicate that these events signal the need for immediate investigation and response through root cause analysis, a systematized process to identify variations in performance that cause or could cause a sentinel event. Suggested steps in such an analysis are briefly summarized in the Patient Safety box on page 19. Whereas TJC data collection focuses on sentinel events, it also recognizes the value of analyzing “close calls” to improve patient safety (Wu, 2011).

TJC categorizes errors reported to it and publishes their frequencies. Examples of perioperative care errors are those that are (1) related to anesthesia; (2) caused by medical equipment; (3) caused by medication error; (4) result in infection, fires, and transfusion reactions; (5) are operative or postoperative; or (6) give rise to unintended retained surgical items (RSIs) or wrong site/patient/procedure surgery. The summary of sentinel events published in 2013 reveals that of 6994 total incidents reviewed from 2004 through 2012, nearly 25% of all incidents reviewed most likely occurred in an operative setting (RSI, referred to by TJC as retained foreign object [RFO], and wrong site procedures). Add in the number of events that could have occurred in the perioperative setting (falls, transfusion and medication errors) and the percentage might reach closer to the 50% figure that Leape and Brennan found in the early 1990s.

National Patient Safety Goals.

Another TJC initiative relates to NPSGs for hospitals and office-based surgery, derived from reported sentinel events. NPSGs are reviewed, updated, or retired each year. See the Patient Safety box on page 19 for an overview of the 2013 NPSGs for hospitals and the Patient Safety box on page 20 for elements of performance for the NPSG related to labeling medications.

TJC also publishes NPSGs for office-based surgery. These are not excerpted here because the goals for patients in both settings are almost the same. Although initially surprising, this similarity is understandable. Even though patients in office-based surgery settings tend to be of healthier physical status classifications as set out by the American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) (see Chapter 5), one could argue that error prevention procedures in office-based surgery facilities nevertheless must be rigorous because these smaller facilities are less likely to have available the hospitals’ wider array of emergency and corrective equipment and personnel. In addition, office-based and ambulatory perioperative staff provides most patient and family discharge education and preparation, unlike inpatient care settings (Ambulatory Surgery Considerations) (Patient and Family Education). Finally, causes of infection and patient defenses against infection do not differ based on the location of the surgical procedure.

Universal Protocol.

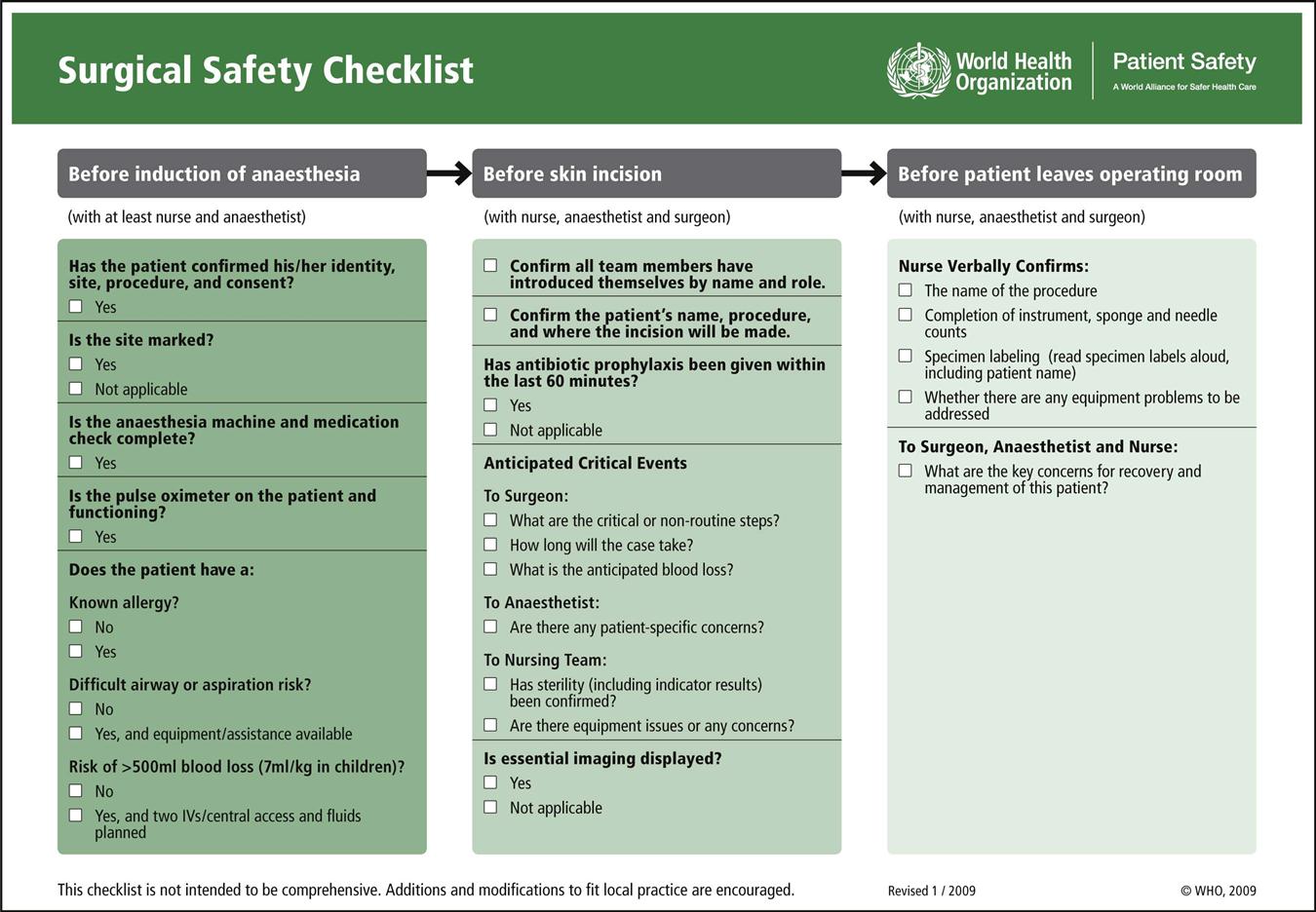

TJC introduced its required safety practice under the nomenclature, Universal Protocol, now incorporated into the NPSGs. Key features of the Universal Protocol, as codified in the NPSGs, are performing a preoperative verification process; marking the operative site; and conducting a time-out immediately before starting the procedure. A properly performed time-out includes information about the patient and procedure, as discussed in more detail later in this chapter.

U.S. Government Agencies

Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services.

As part of the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (DHHS), the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) is the federal agency charged with administration (including regulations for payment) of the Medicare, Medicaid, and multiple state Children’s Health Insurance Programs (CHIP), part of Medicaid. It also administers the Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA) (discussed later) and several other health-related federal programs. Significant to patient safety is the decision by CMS to impose financial disincentives for selected unsafe patient care outcomes by refusing to pay for the extra cost of treatment to correct those outcomes. Conversely stated, the agency responsible for paying Medicare claims now provides a financial incentive for safe patient care.

Nonreimbursable claims most relevant to perioperative patient care include the following (CMS, 2012):

• Pressure ulcers, stages III and IV

• Vascular catheter-associated infections

• Catheter-associated urinary tract infections (CAUTIs)

• Administration of incompatible blood

• Foreign objects unintentionally retained after surgery

• Wrong patient, wrong procedure, or wrong site surgeries

• Pulmonary emboli associated with knee and hip replacements

• High readmission rates to facility within 30 days of discharge

CMS regularly reviews and adds conditions pursuant to its federal rule-making process (e.g., it added specific types of readmissions within 30 days of discharge, effective 2013).

CMS notes that it does not consider these listed patient safety concerns more important than others. Rather, it has chosen the selected concerns to emphasize that the facilities deemed responsible now must bear directly otherwise avoidable financial costs of insufficient patient safety controls. Furthermore, CMS regulations prohibit passing these costs on to patients. Most private insurance companies have adopted similar provisions. Thus from a purely risk management standpoint, in addition to potential indirect costs arising from negligence awards and settlements (which can be insured against), facilities now bear the risk of direct, uninsurable, and potentially severe cost disincentives if they fail to avoid the listed conditions though the institution of safe practices.

Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ).

As one of the 12 agencies within DHHS, the AHRQ’s mission is to improve the quality, safety, efficiency, and effectiveness of healthcare for all Americans. This agency is committed to improving care safety and quality by developing successful partnerships and generating the knowledge and tools required for long-term improvement. The central goal of its research is measurable improvements in healthcare in America. These measurable goals include improved quality of life and patient outcomes, lives saved, and value gained.

The overall focus of AHRQ activities is threefold:

• Safety and quality: reduce the risk of harm

• Effectiveness: improve healthcare outcomes by encouraging the use of evidence

This agency serves healthcare clinicians, facilities and systems, consumers, policymakers, purchasers and payers, and academic healthcare. AHRQ offers nurses and other providers extensive evidence-based resources related to patient safety on its website (ahrq.gov).

The World Health Organization

The United Nations (UN) created WHO to function as its health oversight and coordination authority for all UN member nations who in turn have joined WHO. In 2004, WHO launched the World Alliance on Patient Safety, by which it began to examine patient safety in acute as well as in primary care settings relevant to all WHO member nations. Its action initiatives include Clean Care is Safer Care and Safe Surgery Saves Lives. The focus of the Clean Care campaign is hand hygiene (also referenced in TJC’s NPSGs); it resulted in release of a 2009 WHO guideline for surgical hand preparation (Evidence for Practice). Salient points in the guideline section titled Surgical Hand Preparation: State of the Art include discussion of the time required for preoperative hand antisepsis, encouragement of brushless hand scrubs, and review of antimicrobial hand scrub preparations.

WHO’s Safe Surgery Saves Lives initiative led to publication of its Surgical Safety Checklist. Similar in content to TJC’s Universal Protocol, the WHO checklist adds a third phase, the Sign Out that includes team reviews of outcomes and concerns to be included in the handover (the international term for “hand-off”) to postanesthesia recovery caregivers (Evidence for Practice). Haynes and colleagues (2009) hypothesized that implementation of the WHO Surgical Safety Checklist would reduce complications and deaths associated with surgery. They compared outcomes of surgical patients in eight countries representing widely diverse economic circumstances and patient populations, and found that a 1.5% prechecklist rate of death declined to 0.8% (p = 0.003) with use of the checklist. They also found inpatient complications occurred in 11% of patients before the checklist was implemented and in 7% after introduction of the checklist. They also confirmed tangible improvements in safety outcomes after implementation of the checklist (Haynes et al, 2009; 2011). Notable about WHO’s entry into surgical patient safety is recognition that perioperative adverse events causing complications before, during, and after surgery is a public health problem worldwide.

The Association of periOperative Registered Nurses

For nearly 60 years AORN has addressed perioperative patient safety issues. It represents perioperative patients and perioperative nurses in multiple policy settings, collaborates with TJC, WHO, other nursing associations and surgical alliances, and many safety coalitions to formulate safety statements that directly affect perioperative patient care. AORN provides an array of standards, RPs, guidelines, publications, videos, and tool kits that specifically address patient safety from the perioperative team’s point of view. Tool kits include subjects such as fire safety, correct site surgery, sharps safety, hand-off communications, safe patient handling, and cultural and human factors. RPs and tool kits are evidence based to the extent possible. These AORN undertakings aim to develop real-world strategies to implement perioperative patient care practices. Along with TJC and WHO recommendations, AORN recommendations should be reflected and adopted, to the extent possible, within institutional policies and procedures, and educational curricula.

Other Patient Safety Groups/Coalitions/Companies

Major professional associations representing other perioperative team members (e.g., American College of Surgeons [ACS], American Society of Anesthesiologists [ASA], American Association of Nurse Anesthetists [AANA], Association of Surgical Technologists [AST]) have also issued multiple position statements and clinical recommendations related to patient safety. Many of these are co-issued or mutually endorsed with AORN. This reflects the increasing systems approach to perioperative safety. Additionally, many coalitions with similar patient safety interests have emerged as not-for-profit entities to gather and disseminate data, guidelines, protocols, and goals. For-profit groups are also included in what now may fairly be called a “patient safety industry.” (A partial listing of additional patient safety groups is noted in Box 2-1.)

Perioperative Nursing Safety Issues

Communication and Teamwork

Communication underpins many patient safety issues. Implementation of both the Universal Protocol and the WHO checklist requires enhanced communication within a culture of teamwork (discussed later) (Research Highlight). Hand-off/handover protocols have joined traditional clinical written documentation records to improve communication further in perioperative settings. Research continues in the use of perioperative patient care checklists in a variety of settings and situations (Research Highlight).

Checklists and protocols alone, however, cannot enhance meaningful communication without an equal commitment to teamwork, trust, and respect. Ultimately, improved communication is imbedded in human factors, culture, and social systems, all of which are more complex than checklists, mnemonics, and acronyms (Bliss et al, 2012; de Vries et al, 2011).

Clinical Documentation

The written clinical record is the historical anchor of communicating perioperative patient information. Evidence suggests, however, that a written (or digital) record is inadequate as the sole perioperative communication tool. More enhanced communication initiatives such as safer surgery briefings and hand-offs now augment the written record. Nonetheless, whether documented on paper or digitally, the clinical record remains foundational in assuring a safer patient experience and provision of information to future care areas.

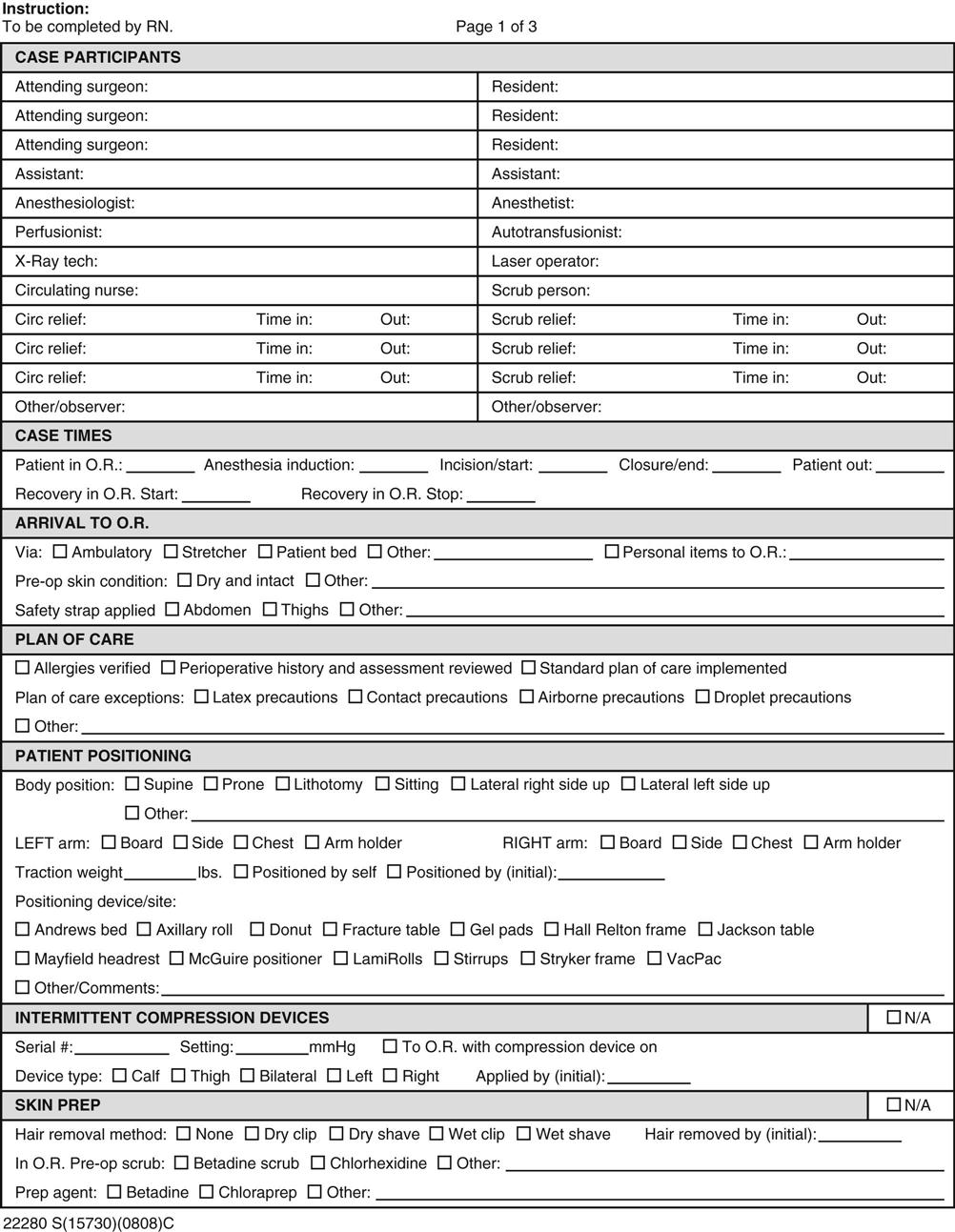

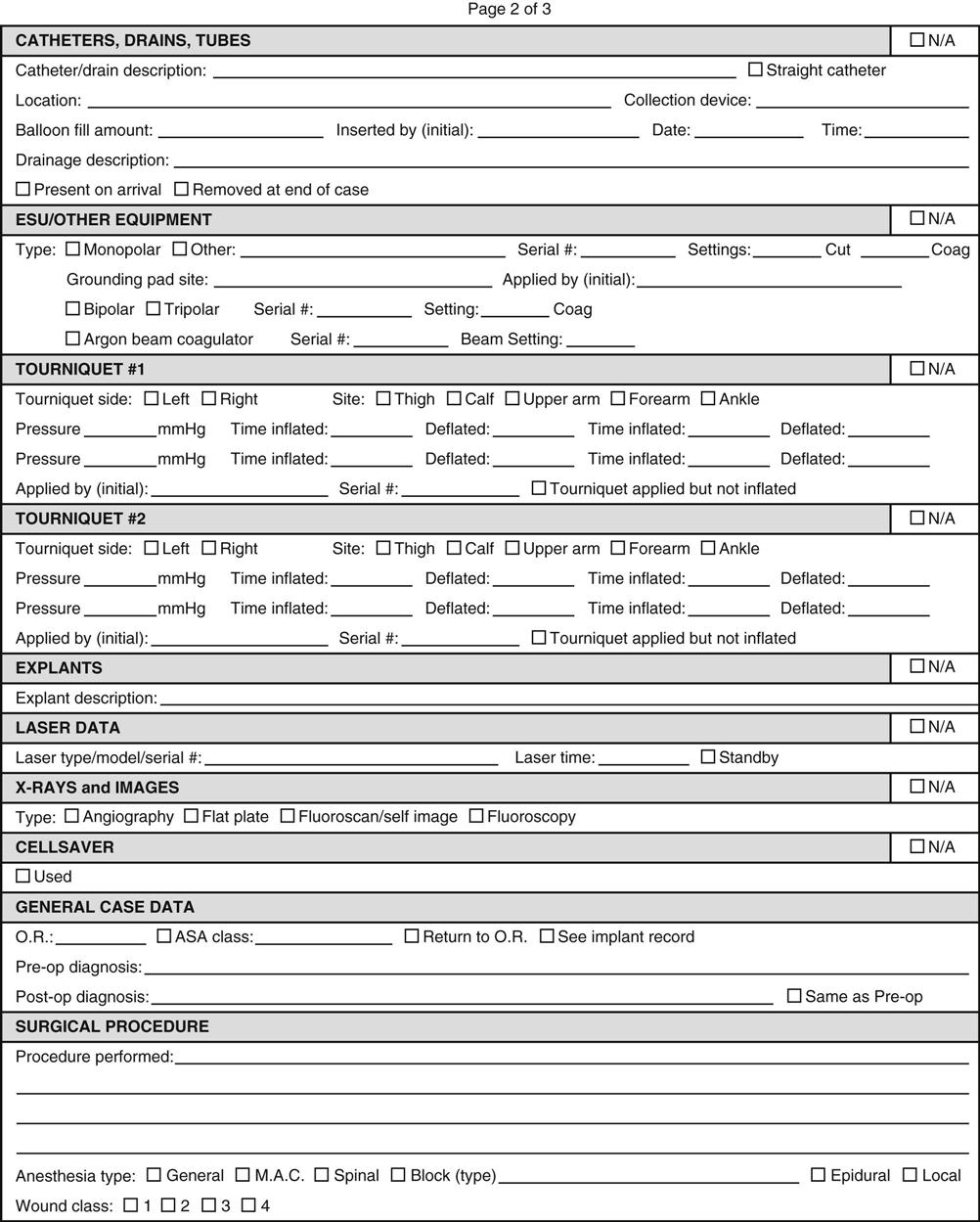

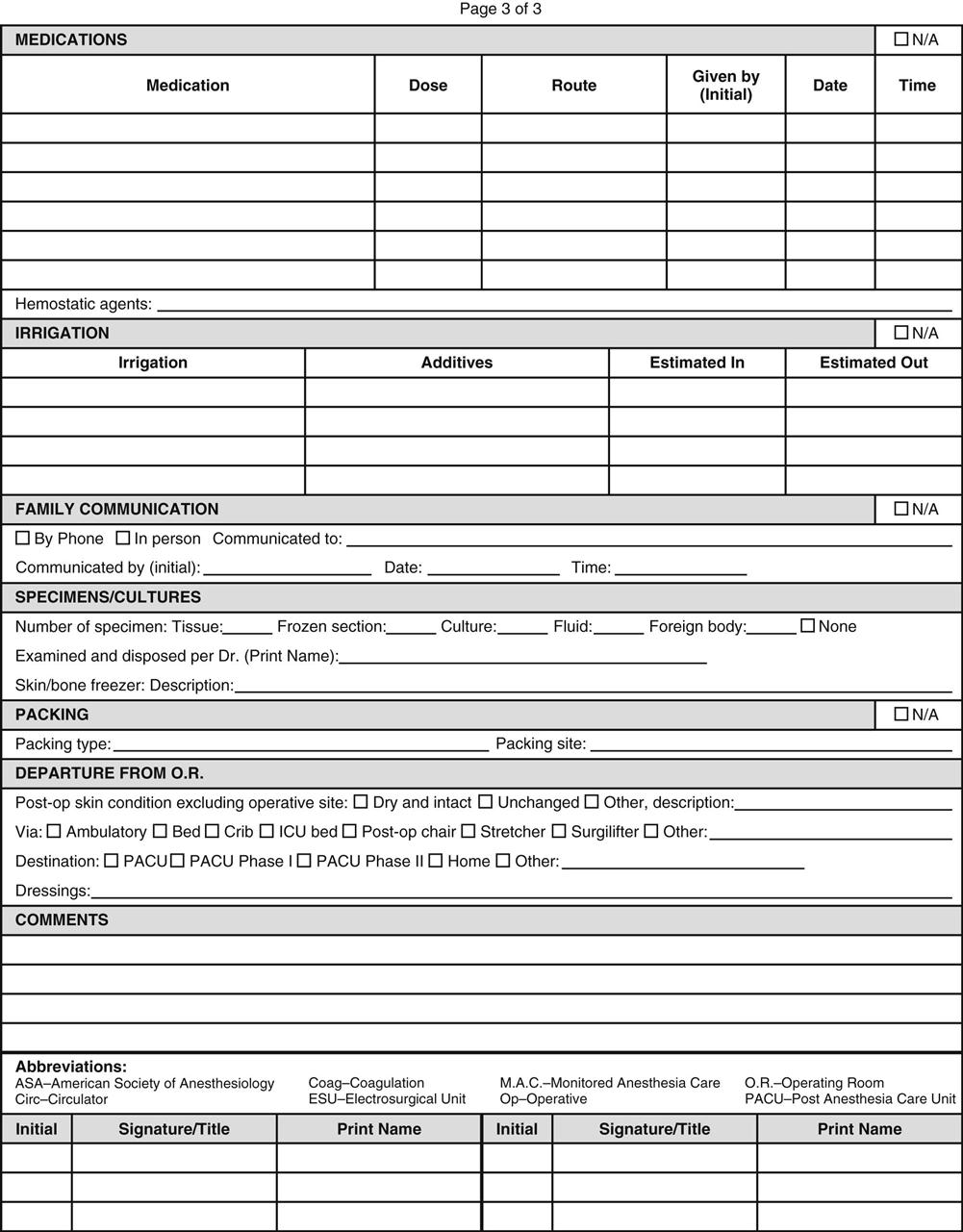

Facilities where operative and other invasive procedures occur maintain records of each operation that must comply with state and federal regulations as well as with accreditation requirements. Those operative records include preoperative diagnosis, surgery performed, a description of findings, specimens removed, postoperative diagnosis, and names of all individuals participating in intraoperative care. Additional key components include positioning and stabilizing devices, electrosurgical unit number and settings, medications, and evidence of ongoing assessment and additional actions taken (a sample intraoperative record is shown in Figure 2-1). The operative record is a permanent part of the patient’s medical record. Note that nearly all components of perioperative clinical documentation relate directly or indirectly to patient safety and injury prevention.

Proper perioperative nursing documentation describes assessment, planning, and implementation of perioperative patient care reflecting individualization of care and evaluation of patient outcomes. Any and every unusual or significant incident pertinent to patient outcomes must be documented as well as all remediation efforts related to the patient’s care. The facility’s risk manager may require additional documentation. Only objective information directly related to the specific patient is included in the patient’s record (e.g., it is inappropriate to record personal opinions or to describe circumstances surrounding an event except as they appear to affect the patient directly).

Thoughtfully designed perioperative nursing documentation tools include defined elements in a format to minimize time needed for the documentation process (e.g., checklists). Ideally, collaboration with preoperative, postanesthesia care unit (PACU), and postoperative nursing units will produce one documentation tool used across all areas, avoiding duplication of patient data by different nursing staff. Increasingly, settings where operative and other invasive procedures are performed use electronic records to enter and track patient care information. Coordination of the content included in the intraoperative record with that in the surgeon’s and anesthesia provider’s intraoperative content can reduce documentation time and provide a more integrated record that streamlines workflow and reduces documentation errors.

Documentation of perioperative patient care in the clinical record simultaneously serves risk management functions. Documentation requirements serve as reminders of actions needed to provide safe care, thus prompting risk reduction strategies and preventing injury. Information in the clinical record also enhances continuity of care, thus reducing future injury. If a patient injury does occur, documentation that preventive measures or other actions to mitigate risks were taken may lessen the likelihood of a successful lawsuit.

Hand-offs/Handovers

As noted, written documentation alone, however crucial, is insufficient to ensure patient safety as care responsibility passes from one team or individual caregiver to another. As they reviewed the evidence related to hand-offs, Friesen and colleagues (2008) defined the transfer of information and responsibility for care of the patient from one provider to another as a hand-off or (internationally) handover. Standardized approaches to hand-off communication further reduce risk for error.

TJC, AORN, and WHO uniformly recommend that time-outs (or “safer surgery briefings”), as well as pre- and postoperative hand-offs, be formalized. In healthcare settings, occasions for transfer-of-care processes, such as hand-offs, include nursing shift changes, temporary relief or coverage, nursing and physician hand-offs from one department to another, various other transfers of information in inpatient settings, and interhospital transfers. The purpose of hand-off communication and reports is to provide essential, up-to-date, and specific information about the patient. Standardized hand-off communication must include an opportunity to ask and respond to questions. For examples of strategies to assist in effective and efficient hand-off communication and reports, see the Patient Safety box on page 28.

Amato-Vealey and colleagues (2008) identified and further developed elements of effective hand-off communication for use at each perioperative hand-off stage, using the SBAR mnemonic (Situation, Background, Assessment, Recommendation). For identification of critical elements for hand-offs from preoperative to intraoperative, see Box 2-2; for hand-offs intraoperatively between scrub persons, see Box 2-3; and for hand-offs from intraoperative to PACU or another postanesthesia recovery area, see Box 2-4.