LIVER

The liver is a vital organ that performs a variety of important functions. It is unique among the internal organs for its ability to regenerate following tissue loss. Glucose homeostasis is maintained by the liver by way of glucose storage (as glycogen), glycogenolysis, and gluconeogenesis. In addition to glycogen, the liver is an important site for iron, copper, triglyceride, and lipid-soluble vitamin storage. A large number of serum proteins, such as albumin, clotting factors, and complement, are synthesized in the liver. Proper liver function is crucial for the catabolism of serum proteins and hormones and for the detoxification of exogenous substances, including many drugs. The liver is also the source of bile production, which is important for fat absorption within the small bowel.

CASE 10-1

The patient is a 46-year-old man who sought medical attention for vague complaints of fatigue, joint pain, and upper abdominal pain. Laboratory studies were performed as part of the patient’s evaluation and showed elevations of serum iron, serum transferrin saturation, and serum ferritin. There were mild elevations of aspartate aminotransferase (AST) and alanine aminotransferase (ALT). Given these findings, a liver biopsy was performed and showed a prominent increase in iron accumulation within hepatocytes and early bridging fibrosis. A diagnosis of hemochromatosis was established. To evaluate for a genetic cause of hemochromatosis (i.e., primary hemochromatosis), analysis of the HFE gene was performed and showed a homozygous C282Y mutation, consistent with primary hemochromatosis (see section “Hemochromatosis” and Figure 10-16).

The liver is located in the right upper quadrant of the abdomen, immediately beneath the diaphragm. Two hepatic lobes are recognized: a larger right lobe and a smaller left lobe. The hepatic artery and portal vein provide the liver with a dual blood supply. The hepatic artery originates from the celiac axis and is the liver’s source of more highly oxygenated blood. The portal vein is formed primarily by the convergence of the splenic vein and superior mesenteric vein. Because of its unique circulation, the portal vein provides the liver with metabolic substrates from the gut and provides a mechanism for ingested substances to be processed before entering the systemic circulation. The hepatic veins empty into the inferior vena cava and carry blood away from the liver and into the systemic circulation. The bile carrying ducts of the liver are called hepatic ducts. The right and left hepatic ducts empty into a common hepatic duct that merges with the cystic duct of the gallbladder to form the common bile duct (Figure 10-1).

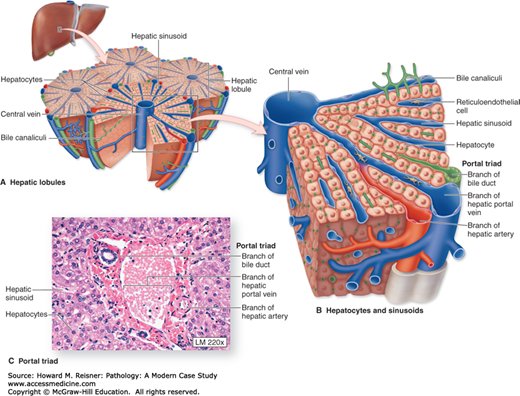

From a microanatomical perspective, the liver is composed of structural units called hepatic lobules. It is easiest to think of the hepatic lobule as a two-dimensional hexagon arranged around a terminal hepatic venule (a.k.a. central vein). Portal tracts (a.k.a. portal triads) are located at the peripheral angles of the hexagon. Portal tracts contain branches of hepatic artery, portal vein, and hepatic duct and are supported by stroma. Surrounding the portal tract is a layer of hepatocytes called the limiting plate. The majority of the hepatic lobule is made up of plates of hepatocytes measuring 1–2 cells thick that radiate from the terminal hepatic venule to the periphery of the lobule. These hepatic plates are surrounded by hepatic sinusoids (Figures 10-2 and 10-3). A reticulin stain can be used to highlight the edges of the sinusoids.

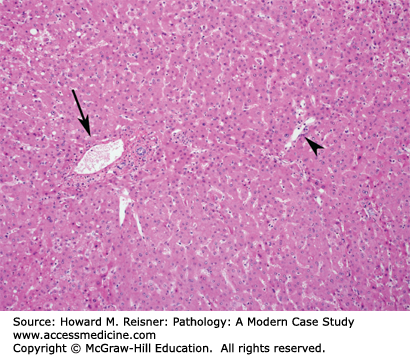

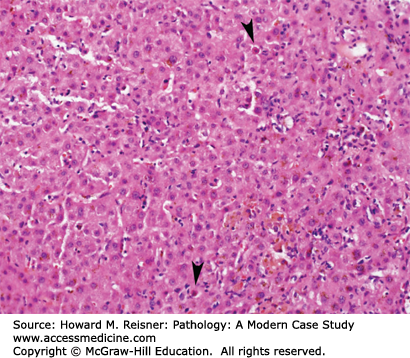

FIGURE 10-3

Hepatic lobule. In this section of liver, one portal tract (arrow) and one terminal hepatic venule (arrowhead) are present. The hepatocytes around the portal tract are referred to as zone 1 hepatocytes and the hepatocytes around the terminal hepatic venule are referred to as zone 3 hepatocytes. The hepatocytes in between are referred to as zone 2 hepatocytes.

Blood from branches of the hepatic artery and portal vein enters the sinusoids at the portal tracts. The blood flows through the sinusoid toward the terminal hepatic venule. Terminal hepatic venules drain into hepatic veins that, as previously noted, drain “processed” blood into the inferior vena cava. The sinusoid–hepatocyte junction is well suited to accommodate the free passage of plasma from the sinusoid to the hepatocyte, and vice versa.

Bile flows in the opposite direction. Bile is secreted by hepatocytes into spaces between adjacent hepatocytes called bile canaliculi. Bile flows from the bile canaliculi to the interlobular (portal tract) bile ducts though periportal bile ductules (a.k.a. cholangioles or canals of Hering).

Functionally, the liver is best thought of in terms of zones. Zone 1 is periportal, zone 3 is perivenular (i.e., around the terminal hepatic venule), and zone 2 is between zones 1 and 3. Zone 1 receives blood with the highest oxygen content, whereas zone 3 receives oxygen-poor blood and is most susceptible to ischemia. There are also metabolic differences between the zones.

The liver is the site of a vast array of non-neoplastic and neoplastic disorders and pathologic evaluation of the liver can be intimidating. Histologically, some non-neoplastic and neoplastic disorders can closely resemble normal liver parenchyma, further complicating evaluation.

Liver failure can be acute or chronic. Acute (fulminant) liver failure is most often caused by viral infection, drug/toxin injury, autoimmune hepatitis (AIH), or hepatic vein obstruction (Figure 10-4). The onset is rapid and, while some cases may be reversible, many cases require liver transplantation to avert death. Chronic liver failure is more insidious in onset and is usually seen in the setting of cirrhosis.

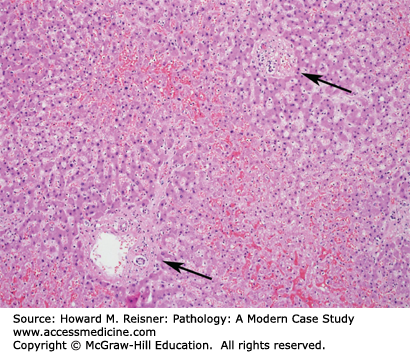

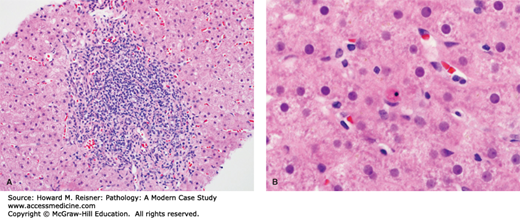

FIGURE 10-4

Fulminant liver failure. In this example of fulminant liver failure, there is panlobular hepatocyte necrosis. Bile duct-like structures are prominent and probably represent a proliferation of pluripotent cells in response to liver injury. The arrow marks a portal tract and the arrowheads mark terminal hepatic venules.

The clinical manifestations of liver failure are broad, which reflects the variety of liver functions outlined at the beginning of the chapter. Jaundice results from an inadequate clearance of bilirubin from the blood. Coagulopathy occurs in part due to reduced synthesis of coagulation factors. Decreased albumin synthesis results in edema due to albumin’s effects on oncotic pressure. Hepatic encephalopathy, renal failure, pulmonary derangements, and endocrine derangements are also manifestations of liver failure.

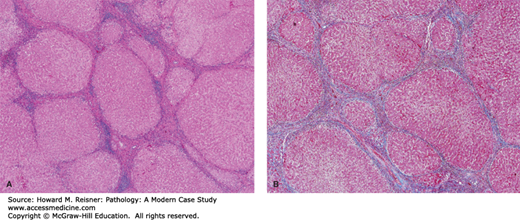

Cirrhosis is the end-stage of several forms of chronic liver disease and is characterized by destruction of the normal liver tissue and the formation of scar tissue (i.e., bands of fibrosis) surrounding regenerative nodules of hepatocytes (Figure 10-5). The most common causes are hepatitis B, hepatitis C, and alcoholic and nonalcoholic steatohepatitis (NASH).

Chronic passive congestion occurs when there is a physical or functional obstruction to the flow of blood through the hepatic vein. This occurs most commonly as the result of congestive heart failure, but can also occur with hepatic vein thrombosis (i.e., Budd–Chiari syndrome).

Grossly, the liver has a mottled cut surface that is said to resemble that of a nutmeg (nutmeg liver). Microscopically, there is dilation of the perivenular sinusoids, which are usually filled with red blood cells. This can cause atrophy of the adjacent zone 3 hepatocytes. Long-standing congestion can result in perivenular and zone 3 perisinusoidal fibrosis. Portal vein thrombosis can cause significant zone 3 hepatocyte necrosis (Figure 10-6).

Increased pressure within the portal vein (i.e., portal hypertension) is caused by increased resistance to blood flow through the portal venous system and is most often the result of cirrhosis. Portal vein thrombosis, hepatic vein obstruction, and, in some parts of the world, hepatic schistosomiasis are other possible causes.

Esophageal varices are a potentially dangerous complication of portal hypertension, as they can rupture and result in massive GI bleeding. Esophageal varices form when increased pressure in the portal venous system causes a compensatory dilation of portal-systemic collaterals that are very small in diameter under normal circumstances. Splenomegaly, ascites, and spontaneous bacterial peritonitis are additional complications of portal hypertension.

Viral hepatitis is far and away the most common infectious cause of hepatitis and will be the focus of the following discussion. Bacterial and fungal infections of the liver are usually part of a broader systemic infection. A number of parasitic infections can occur in the liver and these are relatively rare in developed parts of the world.

Many viruses can show tropism for the liver. For example, yellow fever, a mosquito-borne infection, can cause severe hepatitis with a characteristic pattern of zone 2 hepatocyte necrosis. Herpes simplex virus can cause fulminant liver failure. Of course, any discussion of viral infections of the liver is going to center around the specific viral hepatitides.

Hepatitis A virus (HAV) is an RNA virus that usually results in an asymptomatic infection or an acute self-limited hepatitis. Fulminant liver failure occurs in a very small percentage of cases. HAV does not cause chronic hepatitis. Infection usually occurs through a fecal–oral route and is most common in environments with poor sanitation and contaminated food and water supplies. Infection results in the formation of antibodies. IgM antibodies develop during the acute phase of the illness and fall during recovery, while IgG antibodies develop during the recovery phase and remain present throughout life, conferring resistance to reinfection. The presence of serum anti-HAV IgM antibodies identifies HAV as the cause of acute hepatitis. A vaccine for HAV is available.

Pathology of Acute Viral Hepatitis: The most consistent findings seen in acute viral hepatitis are inflammatory infiltrates and hepatocellular injury. Cholestasis, bile duct injury, and endothelial injury are sometimes encountered. Early hepatocyte injury is in the form of cellular swelling and is thought to be reversible. Irreversible injury is recognized as hepatocyte apoptosis or hepatocyte dropout with replacement by inflammatory cells. The inflammatory infiltrates of acute viral hepatitis are predominantly lymphocytic. The inflammation and hepatocyte injury is found predominantly in zone 3; however, this is not always the case. There is usually less portal inflammation than is seen in chronic hepatitis (Figure 10-7).

Hepatitis B virus (HBV) is a DNA virus that can cause a spectrum of disease. Infection usually occurs via sexual transmission, sharing of contaminated needles, and vertical transmission from mother to child. Most infections in adults result in an asymptomatic infection or an acute self-limited hepatitis, similar to HAV. Approximately 5–10% of infections result in chronic hepatitis that can progress to cirrhosis and is a major risk factor for the development of hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC). A very small percentage of infections can result in fulminant liver failure. A higher percentage of children infected with HBV develop chronic hepatitis, including the majority of vertical transmission cases. The antigens and antibodies associated with HBV infection are summarized in Table 10-1. A vaccine for HBV is available.

| Antigen/Antibody | Definition | Application |

|---|---|---|

| Hepatitis B surface antigen (HBsAg) | Viral surface protein |

|

| Hepatitis B surface antibody (anti-HBs) | Antibody produced in response to HBsAg |

|

| Hepatitis B core antigen (HBcAg) | Viral core protein |

|

| Hepatitis B core antibody (anti-HBc) | Antibody produced in response to HBcAg |

|

| Hepatitis B e-antigen (HBeAg) | Protein produced and released by actively replicating HBV |

|

Hepatitis C virus (HCV) is an RNA virus that causes chronic hepatitis in the large majority of infections. Many infections are asymptomatic. This can result in an extended period of indolent liver injury and unrecognized infectivity. Most infections are acquired through percutaneous exposure to infected blood. Vertical transmission and sexual transmission are much less common. Chronic HCV infection is the most common reason for liver transplantation and is a major risk factor for the development of HCC. Anti-HCV antibodies indicate exposure to HCV. A vaccine for HCV is not yet available.

Pathology of Chronic Viral Hepatitis: Classic findings in chronic viral hepatitis include portal inflammation, interface hepatitis (a.k.a. piecemeal necrosis), lobular necrosis, and varying degrees of hepatic fibrosis. The portal infiltrates are predominantly lymphocytic with lesser numbers of plasma cells, neutrophils, and eosinophils. The infiltrates can be restricted to the portal tracts or they can reach across the limiting plate and be associated with periportal hepatocyte necrosis (i.e., interface hepatitis). The earliest stage of fibrosis is portal fibrous expansion. With progression, fibrous bands extend from the portal tracts into the surrounding lobular parenchyma. When these bands connect with adjacent portal tracts, bridging fibrosis is present. Continued inflammation and injury can ultimately lead to cirrhosis (Figure 10-8).

Chronic HCV infection is frequently associated with steatosis (i.e., fatty change of the liver). Expansive portal infiltrates with germinal center formation are more frequently seen in chronic HCV.

Hepatitis D is a defective RNA virus that requires the presence of HBsAg for propagation. Coinfection with HBV can result in a fulminant hepatitis or more severe chronic hepatitis.

Hepatitis E is an enteric RNA virus that is transmitted through a fecal–oral route and causes epidemics of acute self-limited hepatitis, usually in underdeveloped areas. Interestingly, mortality rates are higher in pregnant woman. Hepatitis E does not cause chronic hepatitis and there is no vaccine currently available.

The most common causes of noninfectious hepatitis include fatty liver disease, AIH, and drug/toxin-induced liver injury.