THE ESOPHAGUS

The esophagus is a muscular tube that extends from approximately the level of the cricoid cartilage to its intersection with the stomach, known as the gastroesophageal (GE) junction. For clinical purposes, the distance to the GE junction is measured starting at the incisors and is generally about 25 cm in the adult.

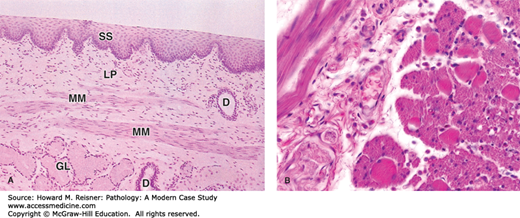

Histologically, the esophagus consists of nonkeratinized squamous epithelium overlying lamina propria and submucosa. Beneath the submucosa is the muscularis propria, consisting of inner circular and outer longitudinal muscle layers. In the upper third of the esophagus, the muscularis propria consists of striated muscle that gives way to smooth muscle in the middle and lower thirds. There is no serosa to the esophagus that allows for spread of tumor into the posterior mediastinum; additionally, the submucosa contains a dense lymphatic system that allows tumors to metastasize to distant sites (Figure 9-1).

FIGURE 9-1

Histology of normal esophagus: (A) Longitudinal section of esophagus shows mucosa consisting of nonkeratinized stratified squamous epithelium (SS), lamina propria (LP), and smooth muscles of the muscularis mucosae (MM). Beneath the mucosa is the submucosa containing esophageal mucous glands (GL) that empty via ducts (D) onto the luminal surface. ×40. H&E. (B) Transverse section showing the muscularis halfway along the esophagus reveals a combination of skeletal muscle (right) and smooth muscle fibers (left) in the outer layer, which are cut both longitudinally and transversely here. This transition from muscles under voluntary control to the type controlled autonomically is important in the swallowing mechanism. ×200. H&E. Mescher AL. Junqueira’s Basic Histology Text & Atlas, 12th ed. McGraw Hill Lange, New York: 2010. Page 260, Figure 15-14.

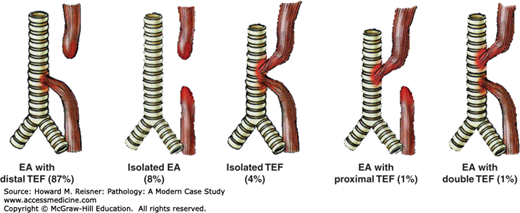

Developmental abnormalities involving the esophagus include atresia, fistulae, webs, and rings. Esophageal atresia occurs when there is incomplete separation between the trachea and esophagus, both of which develop from the primitive foregut, leading to incomplete formation of the esophagus. Frequently, esophageal atresia is accompanied by the development of fistula between the trachea and the esophagus. The most frequent anomaly is that of esophageal atresia with a distal tracheoesophageal fistula (Figure 9-2).

FIGURE 9-2

Developmental abnormalities of the esophagus: EA esophageal atresia, TEF tracheoesophageal fistula. Approximate frequency is indicated as a percentage of all observed cases. Source: Data from http://www.med-ed.virginia.edu/courses/rad/gi/esophagus/congen02.html © 2004 by the Rector & Visitors of the University of Virginia.

Other anatomic abnormalities of the esophagus are frequently secondary to a physical or environmental insult. Esophageal strictures/esophageal stenosis occurs when there is scarring of the esophageal wall following injury. Possible etiologies include gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD), radiation/chemical injury (e.g., ingestion of alkaline substances such as lye), or autoimmune conditions such as scleroderma.

Reflux esophagitis is the most common variant of esophagitis, affecting approximately 10–20% of adults in the Western world. Men and women are affected equally and reflux esophagitis can be seen in all age groups. Typical symptoms include heartburn and dyspepsia.

Reflux is caused by dysfunction of the lower esophageal sphincter (LES) that allows gastric acid to reflux into the esophagus. Common reasons for dysfunction of the LES included anatomic abnormalities such as hiatus hernia, as well as dietary and environmental factors such as obesity, alcohol use, and tobacco abuse.

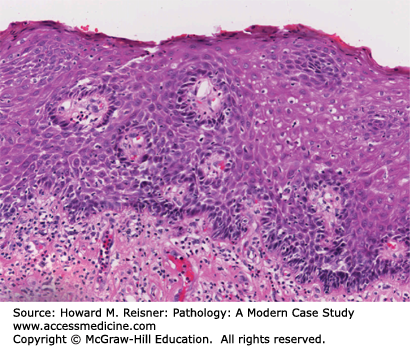

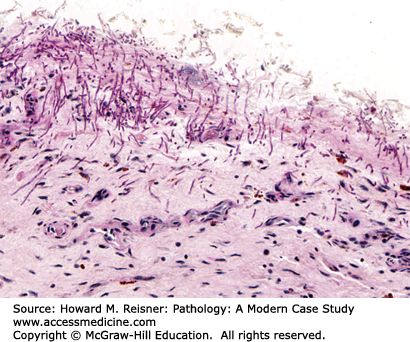

Grossly, the esophagus develops edema and hyperemia; continued reflux can lead to the development of mucosal erosions and ulcerations. Histologically, the squamous mucosa shows a combination of findings that point to a diagnosis of reflux including (1) basal cell hyperplasia, (2) elongation of the lamina propria papillae to greater than two-thirds of the overall height of the squamous epithelium, (3) spongiosis (intra- and extracellular edema, and (4) a variety of inflammatory cells including eosinophils, lymphocytes, and neutrophils (Figure 9-3).

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is less common than reflux esophagitis with an incidence of 0.1–1.2 per 10,000; nonetheless, it is the second most common form of chronic esophagitis. EoE is seen in both pediatric and adult populations. Children with EoE demonstrate failure to thrive and may complain of feelings of food “getting stuck” in their esophagus. Adults are more likely to present with symptoms similar to reflux esophagitis, including complaints of dyspepsia, nausea, and dysphagia.

At endoscopy, the esophagus may demonstrate mucosal rings, exudates, and/or linear furrows. Microscopically, as the name implies, the squamous epithelium shows infiltration by numerous eosinophils with accompanying eosinophilic microabscesses. Additionally, features similar to reflux esophagitis can also be present, including basal cell hyperplasia, lengthening of the lamina propria papillae, and an increase in intraepithelial lymphocytes. Given the overlap between the histologic features of reflux and EoE, it is recommended that patients first be tried on 2 months of high-dose proton pump inhibitor therapy to rule out reflux esophagitis before a diagnosis of EoE is considered (Figure 9-4).

Infectious esophagitis is important predominantly in the immunocompromised populations. Appropriate communication between clinicians and pathologist is often the key to making the correct diagnoses in these patients.

Candida esophagitis is the most common form of infectious esophagitis. Patients are frequently immunocompromised or have preexisting conditions that predispose them to fungal infection. Concurrent oropharyngeal candidiasis is often found as well.

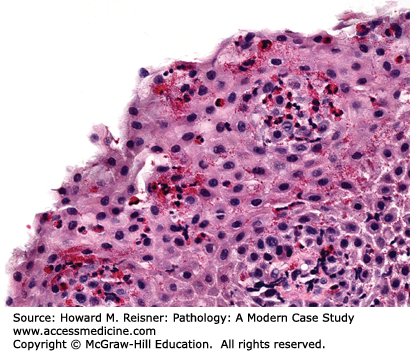

Patients with Candida esophagitis present with dysphagia and chest pain. Endoscopy demonstrates erythematous mucosa covered by white plaques that can be scraped away to reveal underlying ulcers. Histologic findings can be variable with some patients showing minimal changes to the squamous mucosa, while others have dense neutrophilic infiltrates, ulceration, and occasionally, granulomata (Figure 9-5).

CASE 9-1

An overweight 40-year-old man presents to his local physician complaining of burning, gnawing chest pain. The pain is made worse by eating and is worse at night. At endoscopy, linear ulcers are seen in the distal esophagus with accompanying erythema. Biopsy results show squamous epithelium with reactive atypia, increased intraepithelial lymphocytes and rare eosinophils, edema, basal cell hyperplasia, and elongation of the papillae. The patient is counseled to lose weight and treated with proton pump inhibitors with resolution of his symptoms (Figure 9-3).

CASE 9-2

A 35-year-old woman presents to her local emergency room for dysphagia. Pertinent past medical history includes positivity for HIV and prior noncompliance with retroviral therapy. Endoscopy reveals discrete, “punched out” ulcers along the length of the esophagus. Histologically, large, atypical cells are present both at the base of the ulcer and in surrounding endothelial cells with “owls-eye” inclusions in the nucleus. The patient is treated with antivirals and resumes her retroviral therapy with relief from her symptoms (Figure 9-6).

Patients with cytomegalovirus (CMV) esophagitis frequently present with dysphagia, nausea, and chest pain, similar to patients with reflux esophagitis. Unlike reflux esophagitis, however, patients with CMV and other forms of infectious esophagitis have concurrent fever as well. Endoscopy will frequently show ulcers of various types and possibly erosive esophagitis. Biopsies are best taken from the ulcer base, where microscopic examination demonstrates typical ulcer debris with cells containing the classic intranuclear “owl’s eye” inclusions (Figure 9-6).

Herpesvirus (HSV) esophagitis is seen predominantly in patients who are immunocompromised. Similar to CMV, presenting symptoms include dysphagia accompanied by fever. Coexisting herpetic lesions in the genitalia or oral pharynx are seen in a minority of patients.

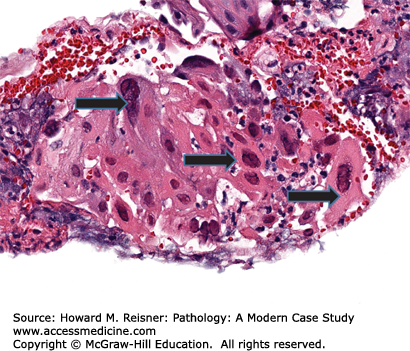

Grossly, HSV esophagitis shows erosive changes to the mucosa and frequently multiple superficial ulcers. Biopsies from the edge of the ulcer show, on histologic examination, ulcer debris with neutrophils and other inflammatory cells. HSV cytopathic effect is characterized by multinucleated cells demonstrating chromatin margination and ground glass nuclei (Figure 9-7).

Barrett esophagus (BE) is a term for a metaplastic, possibly precancerous condition that occurs when the squamous epithelium of the esophagus is replaced by columnar, intestinal-type epithelium with goblet cells. BE develops secondary to chronic injury and inflammation of the esophagus due to conditions such as reflux. The presence of hiatal hernia is also been shown to be a risk factor for BE, while the role of alcohol and smoking is less clear.

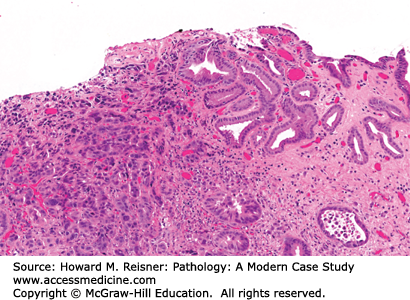

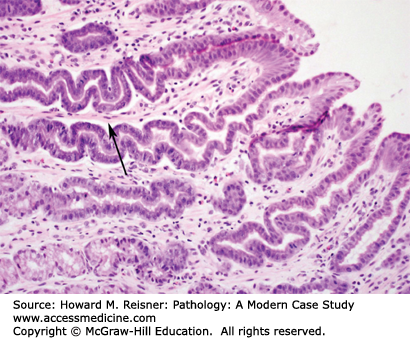

At endoscopy, BE is characterized by the presence of “tongues” of salmon-colored mucosa extending from the GE junction. Research has demonstrated that the length of BE seen at endoscopy correlates with risk of dysplasia and carcinoma. Microscopically, BE is characterized by the replacement of the normal squamous epithelium of the esophagus with intestinal-type epithelium demonstrating a mixture of goblet cells and gastric foveolar-type cells (Figure 9-8).

Case A case study of Barrett esophagus can be found in Chapter 2, Case 2-2.

Benign neoplasms of the esophagus are rare. Those benign tumors that do occur are usually submucosal in location and mesenchymal in origin. The most common is leiomyoma, a tumor arising from smooth muscle cells. Other infrequent tumors of the esophagus include squamous papilloma, inflammatory polyps, and granular cell tumors.

Malignant tumors of the esophagus include squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma. Worldwide, squamous cell carcinoma is the most common form of esophageal carcinoma while adenocarcinoma is now the most common form of esophageal cancer in the United States.

There are worldwide geographic variations in the incidence of squamous cell carcinoma; the highest incidence rates are found in Asia and sub-Saharan Africa with the lowest rates in Europe and the United States. Major risk factors for the development of squamous cell carcinoma include smoking and alcohol abuse; lesser risk factors include poor nutrition and diets low in fruits and vegetables. Patients present with symptoms of dysphagia, weight loss, epigastric pain, and regurgitation.

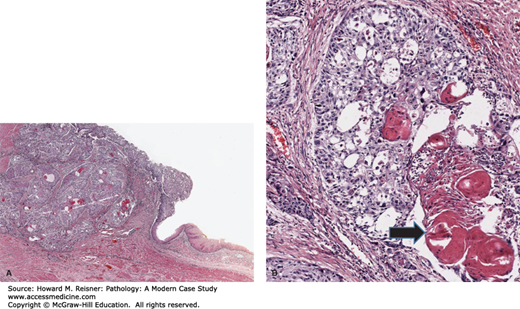

Grossly, squamous cell carcinoma arises predominantly in the middle third of the esophagus, followed by the lower and upper third segments, respectively. The majority of tumors appear as fungating lesions with the remainder demonstrating an ulcerative or infiltrative appearance. Microscopically, squamous cell carcinomas appear similar to squamous cell carcinomas elsewhere in the body, consisting of well, moderately, or poorly differentiated tumors that show invasive nests and islands of squamous epithelium, frequently with generous keratinization. Invasion of the submucosa allows access to the region’s rich lymphatic system, allowing metastases to regional lymph nodes, liver, and lung (Figure 9-9).

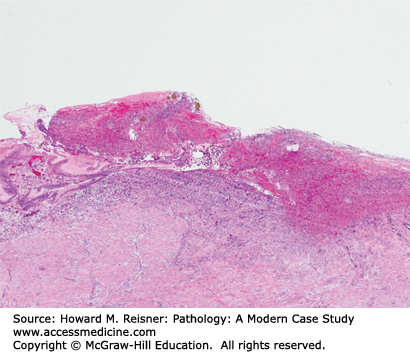

FIGURE 9-9

Squamous cell carcinoma: (A) (low power) Squamous cell cancer of the esophagus (left side of figure) characterized by islands of atypical squamous cells extending into the submucosa. (B) (high-power detail) Note keratin pearls (arrow). Cells demonstrate increased nuclear–cytoplasmic ratio, nuclear atypia, mitotic activity, and apoptotic debris.

Case See Chapter 2, Case 2-2.

Adenocarcinoma of the esophagus is now the most common form of primary esophageal carcinoma in the United States with an incidence of 1 to 5/100,000 population per year in the early 2000s. BE is the single greatest risk factor for the development of adenocarcinoma. Meta-analysis has demonstrated that the incidence of adenocarcinoma in patients with BE is approximately 4/1000 person-years that translates to an approximately 10% risk in patients with BE. Given the relationship between GERD and the development of BE, it should come as no surprise that the clinical presentation of esophageal adenocarcinoma frequently overlaps with that of reflux.

As adenocarcinoma develops from BE, the tumor is therefore found predominantly at the GE junction. Adenocarcinoma typically appears as flat, ulcerated tumors with a minority having a fungating appearance. Residual tongues of BE can sometimes be seen near the tumor bed. Microscopically, esophageal adenocarcinoma is characterized by islands of invasive glands demonstrating various degrees of differentiation. A small number of adenocarcinomas are of the diffuse type and demonstrate signet ring morphology reminiscent of diffuse type gastric adenocarcinoma (Figure 9-10) (see also Chapter 2, Case 2-2).

STOMACH

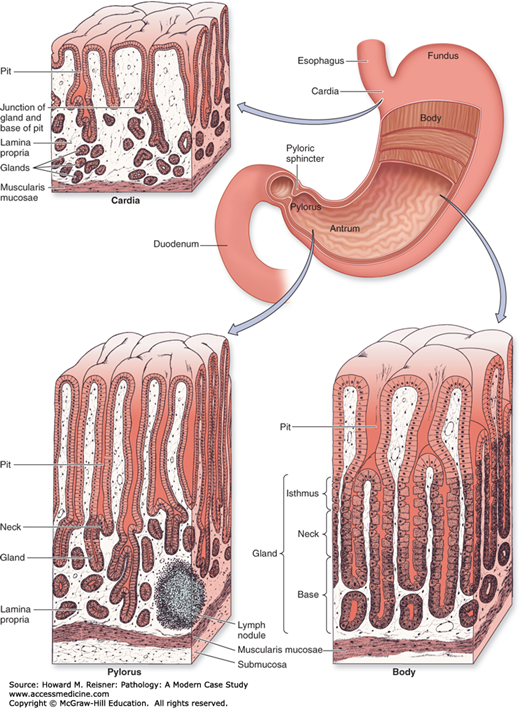

The stomach is a saccular organ located in the upper abdomen. The lumen is continuous with the esophagus at the GE junction and with the duodenum at the pyloric sphincter. The greater and lesser curvatures mark the left lateral and right lateral aspects of the stomach, respectively. The stomach is divided into five anatomic regions. The cardia is the most proximal region of the stomach and extends a very short distance from the GE junction (usually less than 5 mm). The fundus is the dome-shaped upper portion of the stomach, located to the left and above the GE junction. The body, or corpus, makes up the majority of the stomach and extends from the fundus to the antrum. The antrum makes up the distal third of the stomach and extends to the pylorus/pyloric sphincter, which is surrounded by a smooth muscle layer that controls the passage of food from the stomach to the duodenum. The gastric rugae are a series of mucosal folds that are prevalent in the fundus and body and allow the stomach to expand with a meal (Figure 9-11).

FIGURE 9-11

Regions of the stomach. The stomach is a muscular dilation of the digestive tract where mechanical and chemical digestion occurs. The muscularis consists of three layers for thorough mixing of the stomach contents as chyme: an outer longitudinal layer, a middle circular layer, and an inner oblique layer. The stomach mucosa shows distinct histological differences in the cardia, the fundus/body, and the pylorus. Cells that secrete HCI and pepsin are restricted mainly to the body and fundus regions. Glands of the cardia and pylorus produce primarily mucus. Source: Mescher AL. Junqueira’s Basic Histology Text & Atlas, 12th ed. McGraw Hill Lange, New York: 2010. Page 261, Figure 15-15.

CASE 9-3

The patient is a 47-year-old healthy man who underwent an upper gastrointestinal (GI) endoscopy for mild dyspepsia. Endoscopic examination of the stomach revealed a few small superficial erosions within the gastric antrum. Representative lesions were biopsied for microscopic evaluation by a pathologist. Additional biopsies were obtained for Campylobacter-like organism (CLO) testing, which demonstrated the presence of urease activity. The following day, microscopic examination of the tissue showed mild active (neutrophilic) gastritis, severe chronic gastritis, and numerous Helicobacter organisms along the mucosal surface, consistent with Helicobacter gastritis. He was given prescriptions for antibiotics and a proton pump inhibitor, but failed to complete the treatment. Several years later, he underwent a follow-up upper GI endoscopy that showed multiple shallow gastric ulcers and prominent gastric folds. Biopsies were obtained and showed the presence of gastric marginal zone B-cell lymphoma, which has arisen from mucosa-associated lymphoid tissue (MALT) in the presence of chronic Helicobacter gastritis (see section “Marginal Zone B-cell Lymphoma” and Figure 9-20).

The gastric wall, from inside to outside, consists of the mucosa, submucosa, muscularis propria, and serosa. From the mucosal surface, gastric pits extend down to the secretory glands, providing a conduit for gastric secretions to enter the gastric lumen. The composition of gastric glands varies depending on the anatomic region of the stomach. The gastric body and fundus contain an abundance of oxyntic (fundic) glands. These glands contain chief cells (secrete pepsinogen), parietal cells (secrete hydrochloric acid), and scattered endocrine cells. In the cardia, the glands contain mucous secreting cells or a mixture of mucous secreting cells and oxyntic cells. In the antrum and pylorus, the glands contain mucous secreting cells and endocrine cells (Figure 9-12).

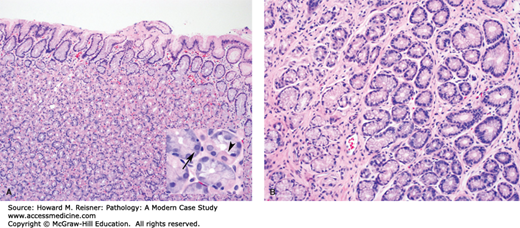

FIGURE 9-12

Normal gastric mucosa. (A) The epithelial component of the gastric mucosa consists of surface foveolar epithelium that is connected to the deep secretory component by gastric pits. In the body and fundus, the secretory component is predominantly made up of oxyntic glands. The inset highlights a parietal cell (arrowhead) and a chief cell (arrow). (B) In the cardia, antrum, and pylorus, the secretory component is predominantly made up of mucous secreting cells.

A variety of developmental disorders, inflammatory disorders, and neoplasms can be seen in the stomach.

With the exception of pyloric stenosis, developmental disorders of the stomach are relatively rare and include congenital diaphragmatic hernias, duplications, diverticula, cysts, atresias, and congenital membranes.

The pathologic hallmark of congenital pyloric stenosis is pronounced thickening of the inner circular layer of the muscularis propria of the pyloric sphincter. This thickening, likely in association with functional abnormalities of peristalsis, results in a narrowing of the pyloric canal that in turn obstructs the gastric outlet.

Clinically, this manifests as projectile vomiting during the first month of life. The ongoing loss of hydrochloric acid can lead to a hypochloremic metabolic alkalosis. The treatment of pyloric stenosis is surgical incision of the thickened pyloric smooth muscle (myotomy). Most patients have an excellent response to surgical intervention.

Inflammatory disorders are an important category of stomach disease and are frequently encountered in the clinical setting.

Acute hemorrhagic gastritis results from a breakdown in the mucosa’s protective mucous-bicarbonate barrier, which leads to mucosal hemorrhage, erosion, and ulceration. The amount of hemorrhage can be quite substantial, and even fatal in some cases. Common causes include severe physiologic stress (e.g., burn injuries), aspirin and nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory use, and excessive ethanol consumption.

Examination of the stomach shows areas of mucosal hemorrhage that can range from small petechial hemorrhages to large confluent areas of hemorrhage. Discrete ulcers can be present and these can, on occasion, extend deeply into the stomach wall. Microscopically, there are variable degrees of mucosal necrosis and hemorrhage, usually accompanied by acute (neutrophilic) inflammation.

Clinical management involves maintaining hemodynamic stability, if significant hemorrhage is present, and restoring the integrity of the mucous-bicarbonate protective barrier by removing any offending agents and lowering gastric acid secretion through the use of histamine receptor antagonists and proton pump inhibitors. Prophylactic use of histamine receptor antagonists is common in the management of hospitalized patients to protect against “stress ulcers.”

The term “chronic gastritis” encompasses a spectrum of stomach disorders, which are usually accompanied by a chronic inflammatory infiltrate. These disorders can present with dyspepsia but are often asymptomatic.

Helicobacter gastritis is a common chronic inflammatory disorder of the stomach caused by infection by H. pylori, and less commonly H. heilmannii. In addition to chronic gastritis, H. pylori infection can lead to peptic ulcer disease of the stomach and duodenum, atrophic gastritis, gastric MALT lymphoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma. Infection results from the ingestion of Helicobacter organisms, which are spiral-shaped gram-negative rods. Infection rates increase with age and are highest in developing parts of the world.

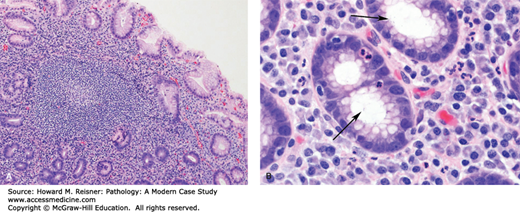

Examination of the stomach shows nonspecific mucosal changes, including erythema, erosions, and atrophy. Microscopically, mucosal biopsies show chronic gastritis, characterized by increased numbers of lymphocytes and plasma cells within the lamina propria (i.e., supportive loose connective tissue surrounding epithelial elements within the mucosa). Lymphoid follicles with germinal centers are often present and are highly specific for Helicobacter gastritis. During active infection, there is often an element of active (neutrophilic) gastritis. Neutrophils can be seen infiltrating the lamina propria, surface epithelium, gastric pits, and gastric glands. Helicobacter organisms are a noninvasive pathogen. They colonize the protective mucous layer and adhere to the surface epithelium. The neutrophilic component resolves quickly following treatment. The chronic inflammatory infiltrate resolves at a much slower pace and can still be present in endoscopic biopsies, even after successful eradication of the infection (Figure 9-13). Treatment involves a combination of proton pump inhibitors, bismuth, and antibiotics.

FIGURE 9-13

Helicobacter gastritis. (A) Note the dense lymphoplasmacytic infiltrate in the lamina propria with a characteristic germinal center. (B) A higher magnification view shows H. pylori organisms (arrows) within the superficial portion of the gastric pit. Note the associated intraepithelial neutrophils.

QUICK REVIEW Helicobacter Gastritis

H. pylori infection is a common cause of chronic gastritis.

Infection can also lead to peptic ulcer disease of the stomach and duodenum, atrophic gastritis, MALT lymphoma, and gastric adenocarcinoma.

Acute inflammation and lymphoid infiltrates with germinal centers are highly suggestive of infection.

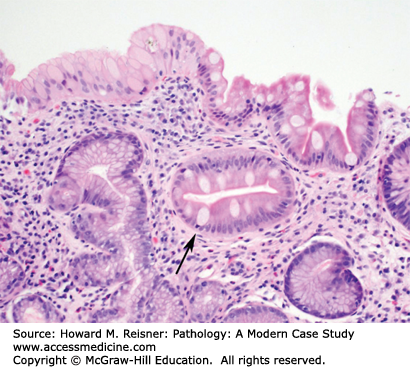

Atrophic gastritis is a gastric disorder characterized by progressive loss of normal gastric glands with replacement by fibrous tissue and metaplastic intestinal epithelium. There are two major categories: autoimmune gastritis and multifocal atrophic gastritis. Both forms can result in dyspepsia, prompting endoscopic evaluation; however, they are most commonly asymptomatic and can be discovered during the work-up of other upper GI complaints. Atrophic gastritis, regardless of the etiology, increases a person’s chances of developing gastric carcinoma. Intestinal metaplasia is thought to be a precursor lesion for dysplasia and carcinoma, similar to the sequence seen in Barrett esophagus (Figure 9-14).

Autoimmune gastritis is a form of atrophic gastritis that involves the body and fundus and is associated with serum autoantibodies to parietal cells and intrinsic factor. The precipitating factor that leads to the development of autoimmune gastritis is uncertain. Autoantibody-mediated destruction of parietal cells leads to progressive parietal cell loss and hypochlorhydria. Achlorhydria can occur in advanced cases. Chief cell loss also occurs, resulting in decreased pepsin activity. In response to decreased acid secretion, G cell hyperplasia occurs in the gastric antrum. G cells secrete gastrin in an effort to increase acid secretion. Gastrin also stimulates endocrine cells (i.e., enterochromaffin-like cells) in the gastric body to proliferate. Thus, neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia and neuroendocrine tumors and carcinomas can occur in autoimmune atrophic gastritis. Autoantibodies to intrinsic factor, a glycoprotein that plays a critical role in vitamin B12 absorption, can lead to pernicious anemia, a megaloblastic anemia resulting from decreased intrinsic factor-mediated absorption of vitamin B12.

This form of atrophic gastritis was formerly known as environmental metaplastic atrophic gastritis. In contrast to autoimmune gastritis, multifocal atrophic gastritis predominantly involves the gastric antrum with possible spillover into the adjacent gastric body. As the name implies, involvement of the antrum tends to occur in a more patchy distribution. Mild hypochlorhydria is possible; however, achlorhydria and pernicious anemia are not encountered. Gastrin secretion is not typically elevated to a significant degree, thus neuroendocrine cell hyperplasia and neuroendocrine tumors are not a usual component. Chronic H. pylori infection is a common cause.

A mucosal erosion is a loss of the superficial portion of the mucosa due to injury and inflammation. Similarly, an ulcer is the loss of mucosa due to injury and inflammation; however, the loss involves the full thickness of the mucosa and may extend deeply within the wall of the stomach. Peptic ulcers are a form of acute and chronic ulceration resulting from breakdown of the mucous-bicarbonate barrier and subsequent gastric secretion-mediated injury. Environmental factors (e.g., smoking, aspirin and NSAIDs use), infection (e.g., H. pylori), systemic illness (e.g., cirrhosis, chronic renal failure), and genetic factors can play a role. Peptic ulcers can occur in the stomach or duodenum. Dyspepsia (i.e., indigestion) and epigastric pain are the most common symptoms. Severe hemorrhage, stomach perforation, and gastric outlet obstruction due to scarring can sometimes occur.

Grossly, gastric ulcers are well-delineated areas of gastric tissue loss, often with characteristic heaped-up tissue at the margin of the lesion. Microscopically, gastric ulcers are characterized by necrosis, an overlying exudate containing necrotic debris and acute inflammatory cells, and granulation tissue and fibrosis at the deep aspect of the lesion (Figure 9-15). It is important to note that gastric ulcers occasionally harbor occult malignancies, which are usually poorly differentiated gastric adenocarcinomas.

Reactive gastropathy is a form of pauci-inflammatory mucosal injury that can occur in response to mucosal exposure to certain substances. Common offending agents include NSAIDs, bile (i.e., duodenogastric reflux), and alcohol.

Grossly, the gastric mucosa is often congested and edematous, and may have focal erosions. Microscopically, there is foveolar hyperplasia that imparts a characteristic corkscrew appearance to the gastric pits, lamina propria edema, vascular congestion, and smooth muscle proliferation within the interglandular stroma. There are occasionally superficial erosions with reparative epithelial changes (Figure 9-16).

The overall rates of gastric adenocarcinoma in the United States are much lower than those seen in other parts of the world, such as Japan. However, gastric adenocarcinoma is still an important cause of cancer-related mortality in the United States.

The depth of invasion at the time of diagnosis can be used to stratify tumors into two categories: early gastric cancer and advanced gastric cancer. Early gastric cancer refers to invasive adenocarcinoma confined to the mucosa or submucosa. This earlier stage of invasion is being detected with greater frequency due to the increased usage of upper endoscopy. Early gastric cancer has a much better 5-year survival rate than its counterpart advanced gastric cancer, which refers to invasive adenocarcinoma that has invaded into the muscularis propria or beyond.

CASE 9-4

The patient is a 62-year-old woman who presented to her primary care physician with a complaint of early satiety (i.e., a feeling of early fullness when eating). As part of the workup, an upper GI endoscopy was performed, which showed an area of tissue bulging into the lumen of the stomach with intact overlying mucosa. Several biopsies were obtained. The pathologist made a diagnosis of GI stromal tumor (GIST). A CT scan of the chest and abdomen was obtained, which showed a 5 cm mass originating from the wall of the stomach, as well as multiple metastases to the liver. Because of the advanced stage of disease, a decision was made to treat the patient with chemotherapy. DNA sequencing of the KIT gene (encodes a tyrosine kinase) was performed on the patient’s biopsy material, showing an activating mutation of the gene. Based on these results, the patient was started on imatinib, a tyrosine kinase inhibitor (see section “Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumor” and Figure 9-19).

Morphologically, gastric adenocarcinomas are broadly separated into two subtypes: intestinal type and diffuse type. Intestinal-type adenocarcinomas are gland-forming malignant neoplasms. In general, these tumors develop in older people, and chronic H. pylori infection is a common etiologic factor. The development of these tumors usually follows a sequence of atrophy to intestinal metaplasia to dysplasia to carcinoma (Figure 9-17

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree