Overview

Diseases of the bone include non-neoplastic disorders such as genetic defects (e.g., achondroplasia), osteoporosis, infections of the bone (i.e., osteomyelitis), and Paget disease. The age of the patient and the location of the tumor are very important considerations in the diagnosis of bone tumors. For example, most chondrosarcomas occur in older adults and almost never occur in the bones of the hands, whereas most Ewing sarcomas occur in the diaphysis of long bones of children.

Diseases of the joints include inflammatory and noninflammatory arthritides. The two major types of arthritis are osteoarthritis and rheumatoid arthritis. Wear and tear is one of the major etiologic agents for the development of osteoarthritis, whereas rheumatoid arthritis is considered to be an autoimmune condition. An important molecular topic regarding bone pathology is the receptor for nuclear factor-κβ (RANK), which is expressed on macrophages, monocytes, and preosteoclasts. The binding of RANK ligand (RANKL) to RANK stimulates osteoclastogenesis. RANKL is produced by osteoblasts and marrow stromal cells. Osteoprotegerin binds to RANK and blocks the binding of RANKL; therefore, it is inhibitory.

Inherited Defects in Bone Structure

Overview: There are many inherited conditions that result in abnormalities of bone structure. Three of the more common types, achondroplasia, osteogenesis imperfecta, and osteopetrosis, will be discussed below.

Inheritance pattern: Autosomal dominant; 80% of new cases are the result of spontaneous mutations.

Mutation: Gene for FGF receptor 3 (FGFR3) on the p arm of chromosome 4.

Effect of mutation: FGF receptor 3 (FGFR3) is an inhibitor of cartilage proliferation. The mutation places the receptor in a constant state of activation.

Manifestations of achondroplasia

- Gross: Disproportionate dwarfism with normal trunk length and short extremities, varus and valgus deformities of legs, short fingers and toes, and large head with prominent forehead.

- Microscopic: Narrow and disorganized zones of proliferation and hypertrophy.

Important points: Achondroplasia accounts for 70% of cases of dwarfism. Less commonly, dwarfism may be due to pituitary dysfunction or secondary to a mutation in the growth hormone receptor (Laron dwarfism).

Overview: There are several different types of osteogenesis imperfecta, each one caused by one of several different mutations. Some of the mutations have an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern. Only type I and type II osteogenesis imperfecta, two of the more common forms of the disease, will be discussed in detail here.

Mutations: Gene for α1 and α2 chains of type I collagen.

Effect of mutation: Varies, depending upon mutation. The results vary from phenotypically normal collagen produced in decreased amounts to absence of collagen production.

Two types of osteogenesis imperfecta

1. Type I osteogenesis imperfecta

Mutation: Decreased synthesis of pro-α1(1) collagen chain, which is compatible with normal life span or abnormal pro-α1(1) or pro-α2(1) collagen chains, which produce the complications discussed below.

Manifestations: Increased number of fractures; blue sclerae because of thin layer of collagen, causing choroid to be visible; hearing loss; and defective dentition. Patients can have a normal life span.

Microscopic morphology: Osteoporosis (i.e., decreased bone mass; bones have thin trabeculae).

2. Type II osteogenesis imperfecta

Mutation: Can involve gene for pro-α1(1) collagen chain in autosomal recessive form of the disease or produce an unstable triple helix in autosomal dominant form of the disease.

Manifestations: Death in utero or early perinatal period. Patients have multiple fractures.

Effect of mutation: Decreased resorption of bone by osteoclasts results in increased amount of bone, but the bone is structurally weak.

Types of osteopetrosis

- 1. Infantile malignant osteopetrosis

- Inheritance pattern: Autosomal recessive.

- Manifestations: Fractures, hydrocephaly, anemia, and infections due to decreased hematopoiesis, and hepatosplenomegaly due to extramedullary hematopoiesis.

- Inheritance pattern: Autosomal recessive.

- 2. and 3. Autosomal dominant type I and type II

- Manifestations of both type I and type II autosomal dominant osteopetrosis: Fractures, anemia, and mild cranial nerve defects due to impingement.

- 4. Carbonic anhydrase II deficiency

- Effect of mutation: Inability to excrete hydrogen ions.

Morphology of osteopetrosis

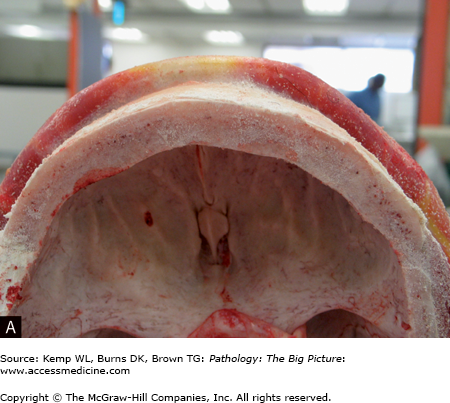

- Gross: No medullary canal; bulbous ends of long bones (i.e., Erlenmeyer flask deformity).

- Microscopic: Woven bone, with obliteration of marrow cavity.

Treatment of osteopetrosis: Bone marrow transplantation, since osteoclasts are derived from monocyte precursors.

Osteoporosis

Overview: Osteoporosis is due to a decrease in bone mass with a subsequent increase in the risk for fractures. Osteoporosis can be localized to one or a few bones (because of disuse) or generalized (involving a majority of the skeletal system). Osteoporosis can be a primary disorder, or it may be secondary to many other disorders.

Forms of primary osteoporosis: Most common forms are type I (postmenopausal osteoporosis) and type II (senile osteoporosis).

- Endocrine causes: Increased levels of parathyroid hormone (PTH) due to an adenoma, or hyperplasia of the parathyroid glands; diabetes mellitus; Addison disease.

- Gastrointestinal cause: Malnutrition.

- Drug causes: Steroids, heparin.

- Increasing age and family history.

- Smoking and alcoholism.

- Decreased estrogen; early or surgical menopause.

- Low body mass index, low calcium diet, and lack of weight-bearing exercise.

- Decreased ability of cells to make bone, which occurs with senility of the bone.

- Decreased physical activity.

- Decreased estrogen, which results in increased level of interleukin-1 (IL-1) and IL-6. IL-1 and IL-6 increase the level of RANK and RANKL and decrease the level of osteoprotegerin.

Clinical presentation of osteoporosis: Vertebral compression fractures with acute back pain and kyphosis; hip fracture. Most compression fractures are asymptomatic.

Osteonecrosis

Osteomyelitis

Overview: Osteomyelitis is infection of the bone. Two of the major forms of osteomyelitis are pyogenic and tuberculous.

Causative organisms: Staphylococcus aureus causes 80–90% of cases. S aureus has a receptor for collagen, which contributes to its pathogenicity. Other organisms that cause osteomyelitis include:

- Escherichia coli and Pseudomonas in intravenous drug users and patients with urinary tract infections.

- Haemophilus influenzae and Group B Streptococcus in neonates.

- Salmonella in patients with sickle cell disease.

Routes of infection: Hematogenous, direct extension from infection in adjacent site, or traumatic implantation.

Bones affected by osteomyelitis: Long bones, vertebral bodies.

Location of infection within the bone

- Neonates: Metaphysis or epiphysis.

- Child: Metaphysis.

- Adults: Epiphysis.

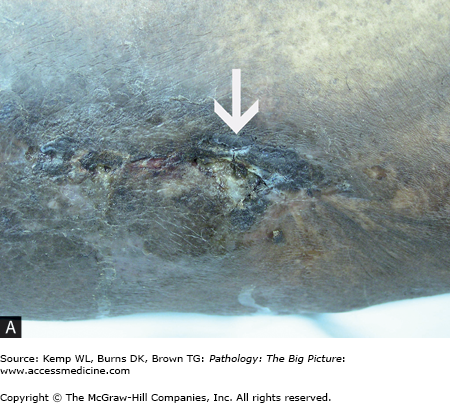

Gross morphology of pyogenic osteomyelitis: The infection can lift the periosteum, which impairs blood flow and can lead to ischemia of the bone. In children, periosteal lifting can lead to abscess formation. The dead bone fragment is called a sequestrum. New bone growth around the sequestrum is called the involucrum. A Brodie abscess is a residual abscess surrounded by rim of new bone growth.

Clinical presentation of pyogenic osteomyelitis

- Signs and symptoms: Malaise, fever, chills, pain, warmth, swelling, erythema; range of motion may be limited by pain.

- Laboratory findings: Leukocytosis with or without a left shift; elevated erythrocyte sedimentation rate. Reactive thrombocytosis may be seen; platelet count can be extremely high.

- Radiographic findings: Destruction of bone; can have radiolucent or radiodense areas in chronic osteomyelitis.

- Diagnosis: Blood cultures are positive in 50% of acute cases. An aspirate with culture is more sensitive and should be performed if possible. Plain radiographs are the first test in the evaluation of suspected osteomyelitis and may reveal soft tissue swelling, periosteal elevation, and subperiosteal resorption and erosion. MRI is the test of choice for evaluating suspected osteomyelitis in diabetic patients. In nondiabetic patients with normal radiographs, a bone scan is indicated to rule out osteomyelitis.

Complications of pyogenic osteomyelitis

- Ruptured periosteum, leading to soft tissue abscess and fistula formation (e.g., draining sinuses to the skin) (Figure 19-1 A and B).

- Pathologic fractures.

- Squamous cell carcinoma in the fistulous tract; sarcomas.

- Suppurative arthritis, which is more common in children and less common in adults.

- Approximately 5–25% of cases of acute osteomyelitis progress to chronic osteomyelitis.

Paget Disease (Osteitis Deformans)

Overview: Paget disease is a non-neoplastic disorder of bone characterized by disorganized growth of bony trabeculae, resulting in a thick, but fragile bone.

Three phases of Paget disease: Osteoclastic activity with hypervascularity; then mixed osteoclastic and osteoblastic stage; and finally, the osteosclerotic stage. The resultant bone is thick, but structurally weak.

Epidemiology: Prevalence in whites more than African Americans or Asians. Occurs in 1–10% of whites and commonly affects middle-aged adults.

Cause of Paget disease: Unknown, but may be viral. May be caused by paramyxovirus, which induces IL-6, which in turn stimulates osteoclasts.

Bones affected: Axillary skeleton (e.g., skull, ribs, vertebrae, pelvic bones) and proximal femur. The disease may be monostotic (15% of cases) or polyostotic (85% of cases).

- Most cases are diagnosed incidentally by radiography.

- The classic presentation is a patient who complains that his hat size is enlarging. Increased thickness of the skull can cause headaches.

- Pain caused by microfractures and bony overgrowth impinging the nerves. Patient may also have symptoms caused by impingement of the cranial nerves.

- Pathologic fractures, especially chalkstick–type fractures.

- High-output cardiac failure in initial hypervascular stage. The hypervascularity warms the skin and increases blood flow, functioning as an arteriovenous malformation.

- Sarcoma (1%), usually osteosarcoma or chondrosarcoma. Patients can also develop giant cell tumors.

- Gross: Thick bone.

- Radiographic finding: Thick, coarse cortex.

- Microscopic: Mosaic pattern of lamellar bone.