Overview

The main purpose of the gastrointestinal tract is the transport of food and the absorption of nutrients. Many pathologic conditions of the gastrointestinal tract impair either or both of these functions. The gastrointestinal tract, and especially the colon, is a common site of malignancy. The two main symptoms related to pathology of the gastrointestinal tract are abdominal pain and gastrointestinal hemorrhage.

The differential diagnosis for abdominal pain can be classified as either acute or chronic, based upon the length of time of the pain (Table 14-1). The four categories of the causes of acute abdominal pain are (1) inflammation, including appendicitis, cholecystitis, pancreatitis, and diverticulitis; (2) perforation; (3) obstruction; and (4) vascular disease, including acute ischemia and ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm. The five categories of causes of chronic abdominal pain are (1) inflammation, including peptic ulcer disease, esophagitis, inflammatory bowel disease, and chronic pancreatitis; (2) vascular disease, including chronic ischemia; (3) metabolic disease, including porphyria; (4) abdominal wall pain; and (5) functional causes, including irritable bowel syndrome. The most frequent causes of chronic abdominal pain are functional.

Time Course | General Category | Specific Causes |

|---|---|---|

Acute | Inflammation | Appendicitis, cholecystitis, acute pancreatitis |

Perforation | Peptic ulcer | |

Obstruction | Volvulus | |

Vascular | Acute ischemia, ruptured abdominal aortic aneurysm | |

Chronic | Inflammation | Peptic ulcer, esophagitis, IBD, chronic pancreatitis |

Vascular | Chronic ischemia | |

Metabolic | Porphyria | |

Abdominal wall pain | ||

Functional | Irritable bowel syndrome |

The second main symptom of gastrointestinal pathology is bleeding (Table 14-2). The character of the blood can help identify the source: hematemesis (i.e., vomiting of bright red blood), if the source is gastrointestinal, is most likely due to a source proximal to the ligament of Treitz. Melena (i.e., black, tarry stool) is most often due to upper gastrointestinal bleeding. Hematochezia (i.e., bright red blood per rectum) usually indicates a lower gastrointestinal bleed (or very rapid upper gastrointestinal bleed). The differential diagnosis of upper gastrointestinal bleeding includes gastritis, esophageal varices, and peptic ulcer disease (as a result of erosion into a blood vessel). The diagnosis of the source of an upper gastrointestinal bleed is often made by endoscopy. The differential diagnosis of lower gastrointestinal bleeding includes a rapid upper gastrointestinal bleed, diverticulosis, infections (e.g., Salmonella, Shigella), cancer, inflammatory bowel disease, and anal fissures or hemorrhoids. The diagnosis of a lower gastrointestinal bleed is often determined by flexible sigmoidoscopy or colonoscopy.

Upper GI bleeding | Esophageal varices, esophageal neoplasms, Mallory-Weiss laceration, gastritis, peptic ulcer disease |

Lower GI bleeding | Rapid upper GI bleeding, diverticulosis, infectious colitis, angiodysplasia, IBD, neoplasm, anal fissure, hemorrhoids |

This chapter will discuss pediatric gastrointestinal disorders, pathology of the oral cavity and salivary glands (including leukoplakia and salivary gland tumors); esophageal pathology (including motor disturbances, esophagitis, Barrett esophagus, and tumors); gastric pathology (including acute and chronic gastritis, peptic ulcer disease, and gastric tumors); and small and large intestinal pathology (including causes of diarrhea and constipation, malabsorption, celiac sprue and inflammatory bowel diseases, vascular disorders, causes of obstruction, diverticular disease, and intestinal tumors, including colonic adenocarcinoma and carcinoid tumors).

Pediatric Gastrointestinal Disorders

Overview: Although there are many gastrointestinal disorders associated with the pediatric population, only some of the more common conditions will be discussed below. Some of the conditions discussed below, including congenital pyloric stenosis, duodenal atresia, Hirschsprung disease, and intussusception, most commonly present during infancy and childhood, whereas Meckel diverticulum, a congenital malformation, commonly presents during adulthood or may be asymptomatic throughout the patient’s life.

Epidemiology: 1 in 300–900 births; prevalence in males, with a 4:1 ratio of male to female.

Association: Turner syndrome, trisomy 18, erythromycin.

Clinical presentation of congenital pyloric stenosis

- Symptoms: Projectile nonbilious vomiting, which presents during the second or third week of life.

- Signs: Palpable mass (“olive-shaped”) in the area of the pylorus. Metabolic alkalosis from vomiting.

- Treatment: Surgical incision (pylorotomy).

Microscopic morphology of congenital pyloric stenosis: Hypertrophy of the smooth muscle of the pylorus; may have inflammation of the overlying mucosa and submucosa.

Basic description: Failure of recanalization of the duodenal lumen during weeks 3–7 of embryologic development.

Epidemiology: 1 in 6000 births; more common in patients with Down syndrome.

Clinical presentation of duodenal atresia

- Symptoms: Bilious vomiting in the first 24 hours of life.

- Diagnosis: “Double-bubble” sign and absence of gas distal to the duodenum on plain films.

Epidemiology: 1 in 5000 live births; more common in males, with male to female ratio of 4:1. Commonly associated with Down syndrome.

Pathogenesis of Hirschsprung disease: Aganglionosis of a segment of the intestinal tract as a result of dysfunctional migration of neural crest cells.

Mutation: 50% of cases associated with RET.

Types of Hirschsprung disease

- Long-segment disease: Involves entire colon.

- Short-segment disease: Involves rectum and sigmoid colon.

Complications of Hirschsprung disease: Toxic megacolon (i.e., markedly distended segment of bowel), which can lead to thinning and rupture of the wall.

Clinical presentation: Failure to pass meconium by newborns, followed by constipation. If only a very short segment of intestine is involved, built-up pressure may cause diarrhea.

Basic description: Collapse of a proximal portion of bowel into a distal portion.

Incidence: 2 in 1000 births.

Clinical presentation of intussusception

- Symptoms and signs: Occurs mostly in children aged 2 months to 5 years. Presents with a classic triad of colicky abdominal pain, bilious vomiting, and “currant jelly” stools. A sausage-shaped right upper quadrant mass may be palpated.

- Diagnosis: Concentric circles of bowel wall may be visualized on ultrasound (“target sign”). Contrast enema is usually diagnostic and may be therapeutic as well.

Basic description: Congenital abnormality of the small intestine resulting from persistence of the omphalomesenteric duct; a true diverticulum containing all three layers of bowel wall.

Incidence: Present in 2% of the general population.

Clinical presentation of Meckel diverticulum

- Symptoms: Most are asymptomatic. May present as obstruction or intussusception.

- Diagnosis: Meckel scan (technetium scintiscan).

Important point: Rule of Two’s (all of which apply to Meckel diverticulum): 2% of the population, 2 inches long, 2 feet from ileocecal valve, child younger than age 2, and 2 types of tissue (ectopic stomach or pancreas).

Pathology of the Oral Cavity and Salivary Glands

Overview: Only some of the more common and important conditions that affect the oral cavity and salivary glands, including hairy leukoplakia, leukoplakia, squamous cell carcinoma of the oral cavity, and various salivary gland tumors, will be discussed here.

Morphology

- Gross: White patches of “hairy” hyperkeratotic thickening on the lateral surface of the tongue.

- Microscopic: Hyperparakeratosis, acanthosis; “balloon cells” in the stratum spinosum.

Association: Immunosuppression

- About 80% of patients with hairy leukoplakia have human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection.

- About 20% have immunosuppression due to other causes, including cancer therapy.

Cause of hairy leukoplakia: Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection.

Basic description: White patch on oral mucosa that cannot be scraped off (i.e., it is not candidiasis).

Importance: 5–25% of cases are premalignant. Tobacco use is a major risk factor.

Incidence: About 95% of head and neck tumors are squamous cell carcinoma.

Risk factors: Alcohol and tobacco use.

Mutations: Loss of heterozygosity of 9p21 involving the p16 gene.

Overview: The smaller the gland involved, the more likely the tumor in it will be malignant. The two types of salivary gland tumors discussed here are pleomorphic adenoma and mucoepidermoid carcinoma.

Epidemiology: About 60% of tumors of the parotid gland are pleomorphic adenomas. Pleomorphic adenomas are rare in the minor salivary glands.

Risk factor: Radiation.

Morphology of pleomorphic adenoma

- Gross: Round, well demarcated.

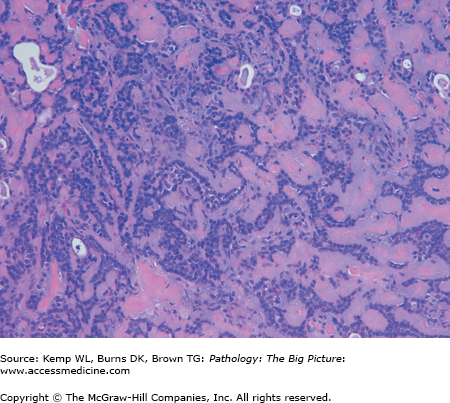

- Microscopic: Three components are ductal cells, myoepithelial cells, and matrix (myxoid, hyaline, or chondroid). Each component forms a variable amount of the tumor (Figure 14-1).

Clinical presentation of pleomorphic adenoma: Slow growing; painless.

Important points

- Although pleomorphic adenomas are benign, they must be completely excised with a wide margin. If the tumor is “shelled out” during surgery (i.e., removed intact with no margins of non-neoplastic tissue), it has a high rate of recurrence.

- Carcinoma can occasionally arise within a pleomorphic adenoma. Termed carcinoma ex pleomorphic adenoma, patients with these tumors have a poor survival rate (40% mortality at 5 years).

Basic description: Malignant tumor of the salivary glands.

Incidence: Most common malignant tumor of the salivary glands; 65% are found in the parotid gland.

Microscopic morphology of mucoepidermoid carcinoma

- Cords and sheets of squamous, mucinous, and intermediate cells. Mucinous cells stain positive with a mucin stain.

- Differentiation: Vary from bland cells to very anaplastic cells, resulting in low to intermediate to high-grade tumors.

Motor Dysfunction of the Esophagus

Overview: Two conditions that cause motor dysfunction of the esophagus are hiatal hernia and achalasia.

Basic description: Condition in which a segment of the stomach protrudes through the diaphragm into the mediastinum.

Types of hiatal hernia: sliding and paraesophageal

- Sliding: A segment of stomach is above the gastroesophageal junction. In effect, the gastroesophageal junction is positioned higher than normal and some stomach is above the diaphragm. A hiatal hernia is due to separation of the diaphragmatic crux.

- Paraesophageal: A small pouch of stomach protrudes through the esophageal hiatus adjacent to the gastro-esophageal junction.

Complications of hiatal hernia

- Gastroesophageal reflux: Many patients with gastro-esophageal reflux have hiatal hernias and many patients with hiatal hernias have reflux, but the two may or may not be related.

- Ulcers, bleeding, and perforation can occur in patients with gastroesophageal reflux.

- Paraesophageal hernias can undergo strangulation or obstruction.

Basic description: Achalasia is a condition caused by increased tone of the lower esophageal sphincter with subsequent failure to relax, and is associated with aperistalsis and distal esophageal dilation.

Mechanism: Loss of intrinsic vasoactive intestinal polypeptide (VIP) and nitric oxide inhibitory innervation of the lower esophageal sphincter; may be primary or secondary. Secondary achalasia is often due to Chagas disease, malignancy, or sarcoidosis.

Complications of achalasia

- Dysphagia, with regurgitation and aspiration of food.

- Squamous cell carcinoma, Candida infection, diverticuli.

Morphology of achalasia

- Gross: Dilation of upper esophagus.

- Microscopic: Inflammation of the esophageal myenteric plexus.

Clinical presentation of achalasia: Progressive dysphagia of solids and liquids. “Bird-beak” esophagus on barium swallow is classic.

Non-Neoplastic Disorders of the Esophagus Associated with Alcohol Use

Overview: Two non-neoplastic disorders of the esophagus associated with alcohol use are Mallory-Weiss lacerations and esophageal varices.

Basic description: Tear in the esophagus at the gastroesophageal junction.

Mechanism of Mallory–Weiss laceration: Reflex relaxation of the lower esophageal sphincter prior to antiperistalsis is overcome by prolonged vomiting.

Risk factors: Alcoholism; hiatal hernia.

Complications of Mallory-Weiss laceration

- Gastrointestinal bleeding.

- Ulcer.

- Perforation of the esophagus with resultant mediastinitis (note: complete rupture of the esophagus is referred to as Boerhaave syndrome).

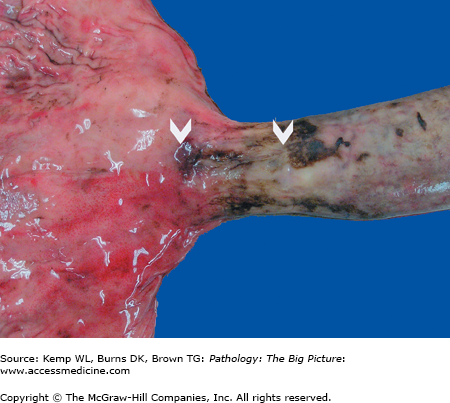

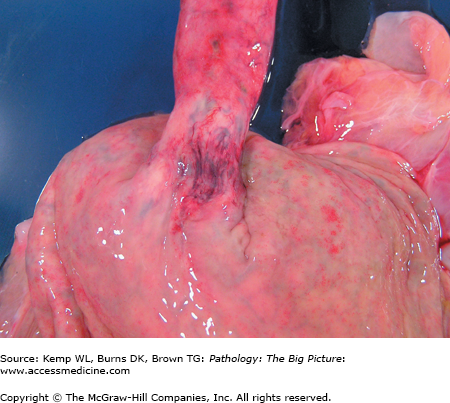

Gross morphology: Longitudinal tears at the gastroesophageal junction (Figure 14-2).

Clinical presentation of Mallory–Weiss laceration: Hematemesis after prolonged vomiting.

Basic description: Dilated submucosal esophageal veins.

Mechanism: Occur in association with cirrhosis of the liver and portal hypertension. The esophageal veins represent an alternative path for bloodflow on its return to the heart, which occurs in patients with cirrhosis. Increased flow through the vessels results in vessel dilation.

Complications of esophageal varices: Gastrointestinal bleeding.

Gross morphology: Dilated veins within the submucosa of the distal esophagus (Figure 14-3).

Clinical presentation of esophageal varices: Hematemesis; melena (black, tarry stool).

Esophagitis and Related Conditions

Overview: Reflux esophagitis, infectious and noninfectious esophagitis, and Barrett esophagus, an important complication of long-term reflux, are discussed in this section.

Basic description: Inflammation of the esophageal mucosa as a result of reflux of the stomach contents.

Mechanisms of GERD

- Increased gastric volume.

- Impaired regenerative capacity of esophageal mucosa and decreased function of antireflux mechanisms.

- Delayed esophageal clearance.

Specific causes of GERD: Alcohol use, central nervous system depressants, hypothyroidism; possibly hiatal hernia with the potential mechanism of removal of the added constriction of the diaphragmatic crura.

Complications of GERD

- Bleeding.

- Stricture formation.

- Ulcer.

- Barrett esophagus (i.e., glandular metaplasia), with resultant risk of adenocarcinoma (see esophageal neoplasms, below).

Microscopic morphology of GERD: Eosinophils, basal zone hyperplasia, and elongation of the lamina propria papilla (Figure 14-4).

Clinical presentation of GERD: Heartburn that occurs after meals or when the patient is supine. The heartburn may be accompanied by a bitter taste or excessive salivation (i.e., water brash) due to a vagal reflex induced by acid in the esophagus. Often, a chronic nonproductive cough is the only symptom of gastroesophageal reflux.

Other causes of esophagitis

- Prolonged gastric intubation, uremia, ingestion of corrosive substances, radiation.

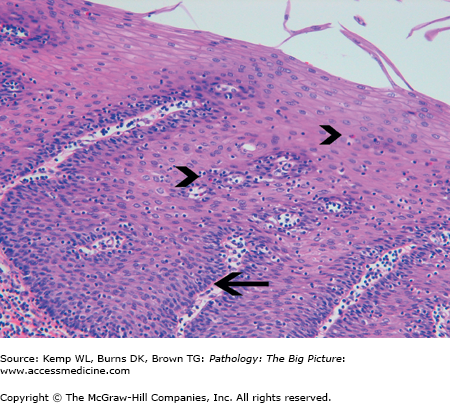

- Nonbacterial causes of esophagitis: Most common causes are infection caused by cytomegalovirus (CMV), herpes simplex virus (HSV), or Candida albicans, and all are associated with patients who are debilitated and have decreased immune function (Figures 14-5 and 14-6).

- Gross morphology: CMV has linear ulcers, HSV has punched out ulcers, and Candida has a white plaque.

- Clinical presentation: Dysphagia and odynophagia.

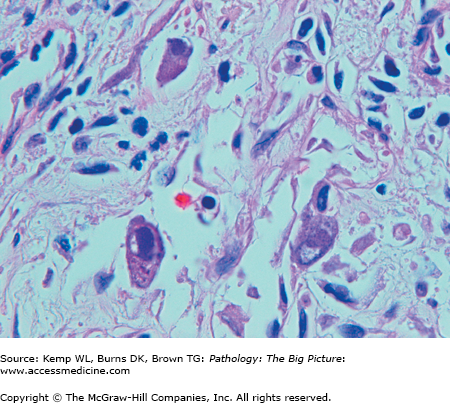

Figure 14-5.

Cytomegalovirus (CMV) esophagitis. CMV is one of the three common nonbacterial infectious causes of esophagitis, usually occurring in patients who are immunosuppressed. Three enlarged cells that have intranuclear inclusions, with a clear peripheral halo, are present in this photomicrograph. Hematoxylin and eosin, 400×.

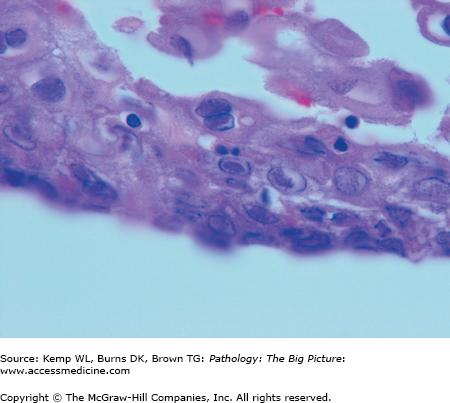

Figure 14-6.

Herpes simplex virus (HSV) esophagitis. HSV is one of the three common nonbacterial infectious causes of esophagitis, usually occurring in patients who are immunosuppressed. These esophageal squamous cells are not enlarged; however, the nuclei have intranuclear inclusions, with a clear halo. These represent Cowdry type A HSV inclusions. Hematoxylin and eosin, 1000×.

Basic description: Glandular metaplasia that occurs in the distal esophagus as a result of chronic reflux of gastric acid into the esophagus.

Pathogenesis: The normal squamous cell lining of the esophagus cannot handle gastric acid, so the epithelium converts to glandular epithelium (metaplasia). If the cause of the reflux is removed, the metaplasia will regress. If the reflux continues, metaplasia can lead to dysplasia, which leads to carcinoma.

Complications of Barrett esophagus

- Ulcer and stricture.

- Esophageal adenocarcinoma: Patients with Barrett esophagus have 30–40 times greater risk than the normal population for the development of esophageal adenocarcinoma. The lifetime risk is 10%.

- Treatment of reflux does not induce regression of Barrett esophagus, and has not been demonstrated to reduce subsequent risk of developing adenocarcinoma.

Morphology of Barrett esophagus (Figure 14-7 A and B)

- Gross: Velvety, gastric-type mucosa above the gastroesophageal junction.

- Microscopic: Columnar glandular epithelium with goblet cells.

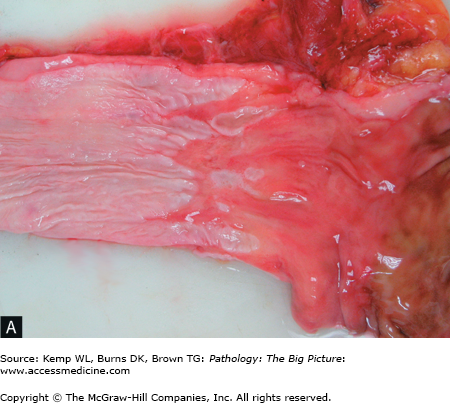

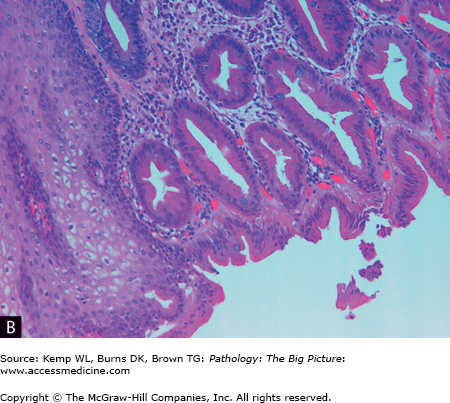

Figure 14-7.

Barrett esophagus. A, The pale smooth tan-white lining of this opened esophagus (left side of image) is interrupted above the gastroesophageal junction by multiple tongues of glistening red-tan gastric-like mucosa. B, The characteristic intestinal-type metaplasia of Barrett esophagus. The squamous epithelium of the normal esophagus is present in the left lower quadrant, and the remainder of the image shows glandular-type epithelium, with a prominent number of goblet cells. Hematoxylin and eosin, 200×.

Other Non-Neoplastic Lesions of the Esophagus

Overview: Although the common non-neoplastic disorders of the esophagus have been discussed above, four more conditions worthy of brief mention are esophageal webs, esophageal rings, true diverticula, and esophageal stenosis.

- Tetrad of esophageal webs, iron deficiency anemia, glossitis, and cheilosis.

- Patients are at risk for squamous cell carcinoma.

Location: A rings are located above the squamocolumnar junction; B rings (also called Schatzki ring) are located at the squamocolumnar junction.

- Zenker diverticulum: Location is the proximal esophagus.

- Traction diverticulum: Location is the mid esophagus.

- Epiphrenic diverticulum: Location is near the gastroesophageal junction.

Esophageal Neoplasms

Overview: The two main types of esophageal neoplasms are squamous cell carcinoma and adenocarcinoma.

Epidemiology: Squamous cell carcinoma is the most common type of carcinoma of the esophagus worldwide, and in the United States, its incidence equals that of adenocarcinoma. Predominance of male to female in a ratio of 2:1; African Americans have a higher risk than whites.

Location: Anywhere along the length of the esophagus.

Risk factors

- Smoking and alcohol use.

- Dysphagia due to esophagitis or achalasia, which increases exposure of mucosa to toxins.

- Plummer-Vinson syndrome.

- Deficiency of vitamin A.

Features of squamous cell carcinoma of the esophagus

- Metastases

- Squamous cell carcinoma in the upper third of the esophagus spreads to the cervical lymph nodes.

- Squamous cell carcinoma in the middle third of the esophagus spreads to the mediastinal, paratracheal, and tracheobronchial nodes.

- Squamous cell carcinoma in the lower third of the esophagus spreads to the gastric and celiac lymph nodes.

- Squamous cell carcinoma in the upper third of the esophagus spreads to the cervical lymph nodes.

- Mutations: Mutations of p53 occur in 50% of tumors. Mutations of p16INK-4.K-ras mutations are rare.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree