12.1 INTRODUCTION TO PARVOVIRUSES

Parvoviruses are among the smallest known viruses, with virions in the range 18–26 nm in diameter. They derive their name from the Latin parvus (small). The family Parvoviridae has been divided into two subfamilies: the Parvovirinae (vertebrate viruses) and the Densovirinae (invertebrate viruses). Some of the genera and species of the subfamilies are shown in Table 12.1.

Table 12.1 Some of the viruses in the family Parvoviridae

| Parvovirinae | Dependovirus | Adeno-associated virus 2 |

| Parvovirus | Minute virus of mice | |

| Feline panleukopenia virus | ||

| Erythrovirus | B19 virus | |

| Bocavirus | Human bocavirus | |

| Densovirinae | Iteravirus | Bombyx mori densovirus |

The subfamily Parvovirinae includes the genus Dependovirus, the members of which are defective, normally replicating only when the host cell is co-infected with a helper virus. Other parvoviruses that do not require helper viruses are known as autonomous parvoviruses.

12.2 EXAMPLES OF PARVOVIRUSES

12.2.1 Dependoviruses

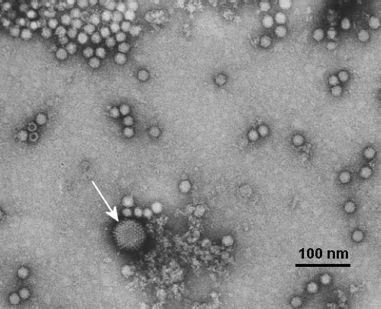

The first dependovirus to be discovered was observed in the electron microscope as a contaminant of an adenovirus preparation (Figure 12.1). The contaminant turned out to be a satellite virus (Section 1.3.4): a defective virus dependent on the help of the adenovirus for replication. The satellite virus was therefore called an adeno-associated virus. Other dependoviruses (distinct serotypes) have since been found in adenovirus preparations and in infected humans and other species. Results of surveys using serological methods and PCR detection of virus DNA indicate that dependovirus infections are widespread.

Figure 12.1 Virions of adenovirus (arrowed) and dependovirus.

Source: Reproduced with permission of Professor M. Stewart McNulty and The Agri-Food and Biosciences Institute.

Not all dependoviruses have an absolute requirement for the help of an adenovirus. Other DNA viruses (e.g. herpesviruses) may sometimes act as helpers, and some dependoviruses may replicate in the absence of a helper virus under certain circumstances.

Dependoviruses are valuable gene vectors. They are used to introduce genes into cell cultures for mass-production of the proteins encoded by those genes, and they are being investigated as possible vectors to introduce genes into the cells of patients for the treatment of various genetic diseases and cancers. One of the advantages of dependoviruses for such applications is the fact that they are not known to cause any disease, in contrast to other virus vectors, such as retroviruses (Section 17.5).

12.2.2 Autonomous parvoviruses

A parvovirus that does not require a helper virus was discovered in serum from a healthy blood donor. The virus, named after a batch of blood labeled B19, infects red blood cell precursors. Many infections with B19 are without signs or symptoms, but some result in disease, such as fifth disease (erythema infectiosum), in which affected children develop a “slapped-cheek” appearance (Figure 12.2).

Figure 12.2 Child with fifth disease.

Source: Reproduced by permission of the New Zealand Dermatological Society.

Other diseases caused by B19 virus include:

- acute arthritis;

- aplastic anemia in persons with chronic hemolytic anemia;

- hydrops fetalis (infection may be transmitted from a pregnant woman to the fetus and may kill the fetus).

In 2005 a new human parvovirus was discovered using a technique for molecular screening of nasopharyngeal aspirates from children with lower respiratory tract disease. The virus is related to known parvoviruses in the genus Bocavirus.

Viruses in the subfamily Densovirinae cause the formation of dense inclusions in the nucleus of the infected cell. Some of these viruses are pathogens of the silkworm (Bombyx mori), and can cause economic damage to the silk industry.

12.3 PARVOVIRUS VIRION

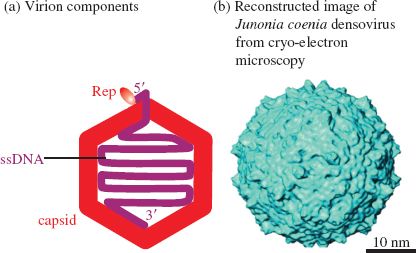

Parvoviruses are small viruses of simple structure with the ssDNA genome enclosed within a capsid that has icosahedral symmetry (Figure 12.3). Negatively stained virions of a parvovirus can be seen in Figure 12.1

Figure 12.3 The parvovirus virion.

Source: (b) Bruemmer et al. (2005) Journal of Molecular Biology, 347, 791. Reproduced by permission of Elsevier.

12.3.1 Capsid

The parvovirus capsid is built from 60 protein molecules. One protein species forms the majority of the capsid structure and there are small amounts of between one and three other protein species, depending on the virus. The proteins are numbered in order of size, with VP1 the largest; the smaller proteins are shorter versions of VP1. Each protein species contains an eight-stranded β-barrel structure that is common to many viral capsid proteins, including those of the picornaviruses (Chapter 14). Within VP1 there is a phospholipase domain that plays a role in penetrating the endosome membrane during entry into a cell.

The virion is roughly spherical, with surface protrusions and canyons (Figure 12.3(b)). At each of the vertices of the icosahedron there is a protrusion with a pore at the center.

12.3.2 Genome

Parvoviruses have genomes composed of linear ssDNA in the size range 4–6 kb. At the 5′ end there is a covalently linked protein molecule; depending on the virus, this protein is known either as Rep (because it is involved in replication) or NS1 (previously defined as non-structural). This protein, together with a short sequence of the DNA to which it is linked, is present on the surface of the virion (Figure 12.3(a)).

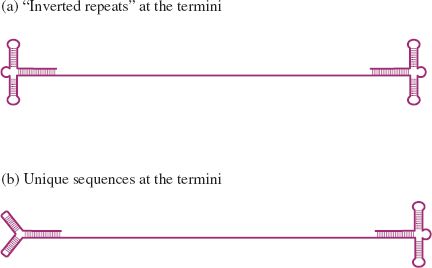

At each end of the DNA there are a number of short complementary sequences that can base pair to form a secondary structure (Figure 12.4). Some parvovirus genomes have sequences at their ends known as inverted terminal repeats (ITRs), where the sequence at one end is complementary to, and in the opposite orientation to, the sequence at the other end (Section 3.2.6). As the sequences are complementary, the ends have identical secondary structures (Figure 12.4(a)). Other parvoviruses have a unique sequence, and therefore a unique secondary structure, at each end of the DNA (Figure 12.4(b)).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree