Papillary Carcinoma

FREDERICK C. KOERNER

FREQUENCY

Papillary carcinoma is an uncommon form of ductal carcinoma in which the neoplastic cells grow on an arborizing fibrovascular skeleton. Early writers did not use the term papillary, in a consistent way, nor did they maintain a clear distinction between the noninvasive and invasive forms of this type of carcinoma. The many and varied definitions of papillary carcinoma have included ductal carcinoma in situ (DCIS) with papillary features in multiple ducts, solitary papillary tumors, cystic papillary carcinomas, and invasive carcinomas with a papillary growth pattern.1,2 Consequently, the literature contains only scant secure data concerning the frequency of this lesion. In a group of carcinomas from 383,146 women in the 1973 to 1998 Surveillance Epidemiology and End Results (SEER) registry, papillary carcinoma accounts for only 0.6%.3 McDivitt et al.4 wrote that invasive papillary carcinoma constituted approximately 1.5% of the cases of operable invasive carcinoma seen at Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, and Fisher et al.1 classified 2.1% of the carcinomas studied in National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project (NSABP) protocol #4 as invasive papillary carcinoma. Among radiologically detected carcinomas, invasive papillary carcinoma accounted for 0.04% in one series5 and 2.8% in another.6 Papillary carcinoma was found in 2 of 169 women (1.2%) who were at least 75 years old when breast carcinoma was diagnosed.7 A greater percentage of male breast carcinomas are papillary, accounting for 2.6% of 2,537 carcinomas in the 1973 to 1998 SEER registry,3 2.7% of a series of 187 cases in Denmark,8 and 8% of a group of 113 tumors seen at the Armed Forces Institute of Pathology.9

RELATIONSHIP BETWEEN PAPILLOMA AND PAPILLARY CARCINOMA

The relationship between benign and malignant papillary tumors of the breast has long been a controversial subject. As early as 1922, Bloodgood10 classified papilloma as a benign condition best managed by local excision. However, other authors, who concluded that papillomas frequently give rise to carcinoma, advocated simple mastectomy to treat breast papilloma.11,12,13 In 1946, Foote and Stewart14 commented that surrounding some lesions “… in which the presence of noninfiltrating papillary carcinoma is quite obvious, there will be additional outlying or adjacent foci in which the degree of structural change is distinctly less advanced and this leads one to believe that preexisting papillomatosis had been present and had undergone malignant transformation.”

A differing point of view was expressed by Stout15 in 1952, when he made the following comment at the Second National Cancer Conference:

Intraductal papillomas are altogether benign and the papillary carcinomas altogether malignant. I have never been able to detect cancer cells intermingled with the cells of a benign papilloma. Therefore in the breast I cannot say I have ever observed what may be interpreted as a carcinoma arising in a benign papilloma. Are benign papillomas precancerous lesions? It is almost impossible to get convincing evidence pro and con on this question for once a papilloma has been removed there is no further chance for that particular one to become malignant.

However, Stout and coworkers16 acknowledged that in situ carcinoma could reside in a papilloma when he stated:

Recognizable nodules of papillary carcinoma almost never show traces of benign intraductal proliferations, so that in doubtful cases if there are microscopic cells which one might be tempted to consider cancerous within an otherwise benign papillary tumor… either these are not cancer cells, or if one chooses to regard them as such, the condition is comparable to cancer in situ. Because we have no proof that this condition has ever led to the development of true clinical cancer, we have classified tumors showing epithelial proliferations of this sort with the rest of the benign intraductal papillary tumors.

One must presume that Stout used the term “clinical cancer” to mean invasive carcinoma. Because papillary lesions with in situ carcinoma did not produce metastases, he evidently chose to classify them as papillomas, but it is clear from the foregoing quotation that he did appreciate the fact that areas with carcinomatous features could be found within benign appearing papillary tumors.17 He recognized the difficulties inherent in proving that carcinoma may have arisen from a previously excised papillary lesion18:

Most attempts to determine the incidence of cancer development from intraductal papillomas by follow-up studies are fruitless because when discovered the papilloma is

removed. All that can then be demonstrated is that… the rate of breast cancer development in either breast following it is no higher than the expected breast cancer development rate for a comparable age group and time period.

removed. All that can then be demonstrated is that… the rate of breast cancer development in either breast following it is no higher than the expected breast cancer development rate for a comparable age group and time period.

Stout and Stewart took part in a study of lesions that had been diagnosed as benign intraductal papillomas from 125 patients treated at the New York Hospital.19 Carcinoma was subsequently detected in the ipsilateral breast of seven patients, typically in proximity to the lesion previously described as a papilloma. The investigators agreed that five lesions originally diagnosed as papillomas had actually been carcinomas. A sixth tumor was confirmed to be a papilloma, and the seventh prior lesion was not reviewed.

A solitary papilloma that has been excised and not found to contain carcinoma or severely atypical hyperplasia is not a precancerous lesion. The risk of detecting carcinoma subsequently in the same breast is low. Overall, fewer than 5% of patients reportedly have developed breast carcinoma after excision of a papilloma, and nearly one-half of the subsequent carcinomas were detected in the opposite breast. In some cases, the proximity of mammary carcinoma and a papilloma is such that they must be regarded as parts of a single lesion. Mingling of the two processes is evidence of carcinoma arising in a papilloma. Usually, the carcinomatous component in these lesions is DCIS. Papillary tumors that have progressed to invasion rarely contain areas of papilloma. A greater risk for the development of carcinoma has been associated with the presence of multiple papillomas and with papillomas that contain in situ carcinoma (see Chapter 5).

CLINICAL PRESENTATION

Age

The literature does not contain well-established reliable information concerning the epidemiologic features of patients with papillary carcinoma. The tumor usually occurs in adults beyond the age of 50 years, and, on average, women with papillary carcinoma are older than women with other types of breast carcinoma. In a review of 35 cases, Fisher et al.1 stated that “The lesion occurs with a significantly high frequency among … postmenopausal women.” Other publications echo this observation.6,20 Small series and case reports document the occurrence of papillary carcinomas in women as young as 29 years21 and as old as 91 years.22 Grabowski et al.23 calculated a mean age of approximately 70 years using cases in the California Cancer Registry classified as intracystic papillary carcinoma. Men with papillary carcinoma span the same range of ages. According to Fisher et al.,1 papillary carcinoma occurs more commonly in “non-Caucasians.”

Location

Nearly 50% of papillary carcinomas arise in the central part of the breast, and as a consequence, nipple discharge has been described in 22% to 34% of patients.24,25 Bleeding from the nipple occurs in a higher percentage of patients with papillary carcinoma than in women with a papilloma. Paget disease is rarely found in association with papillary carcinoma, but may be present if the lesion arises from major lactiferous ducts within the nipple or if there are additional foci of DCIS in the nipple. Most papillary carcinomas have a slow growth rate. Patients have reported the presence of a discharge or a mass for prolonged periods, and a duration of symptoms for a year or more before presentation is not unusual.24,25,26,27

Imaging Studies

Invasive papillary carcinomas present varied radiologic findings. Mammograms often display a multinodular pattern of increased density in a segmental distribution,5,6 and the nodules sometimes occupy only a single quadrant.5,6 Solitary masses also occur frequently.20 The masses typically appear round, oval, or lobulated,5,20,28 and their borders may be either well defined5,22 or ill defined.20,29 The differential diagnosis for a well-defined mass includes fibroadenoma (FA), benign cystic lesions, medullary carcinoma, and mucinous carcinoma. Coarse, irregular calcifications may develop in areas of sclerosis or resolved hemorrhage in papillomas or in papillary carcinomas. Calcifications are not abundant in most papillary carcinomas, and when present, they tend to be punctate and associated with the intraductal component.22 In one case,30 the calcifications appeared “rod like.” The sonographic features of papillomas and papillary carcinomas overlap.31,32 Sonography of invasive papillary carcinomas typically demonstrates masses that appear well defined, solid or mixed solid and cystic, inhomogeneous, and hypoechogenic with posterior enhancement.5,20,30 The presence of a nonparallel orientation, echogenic halo, posterior acoustic enhancement, and calcifications suggests the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma rather than papilloma.32 Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of one case33 yielded T1-weighted images showing an irregular mass with moderately decreased signal intensity; on T2-weighted images, the carcinoma appeared hypointense. After gadolinium injection, mild and inhomogeneous enhancement was noted. Other cases of invasive and noninvasive papillary carcinoma did not demonstrate specific findings.34 In fact, MRI failed to detect 2 of 13 papillary carcinomas and classified 6 of the remaining 11 as benign or probably benign. Extension of papillary carcinoma into adjacent ducts cannot be reliably assessed by mammography. Galactography may be used to examine patients who have nipple discharge to determine whether papillary lesions are multicentric.35 Filling defects in ducts outlined in a galactogram may be due to papillomas or papillary carcinoma. Clinically detectable enlargement of axillary lymph nodes (ALNs) is unusual except in patients with massive tumors, which tend to develop areas of hemorrhagic necrosis.

GROSS PATHOLOGY

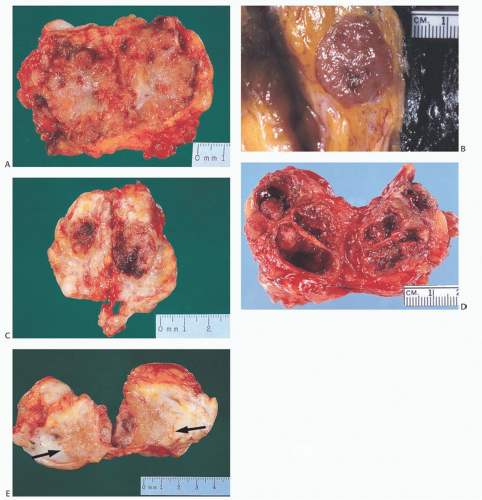

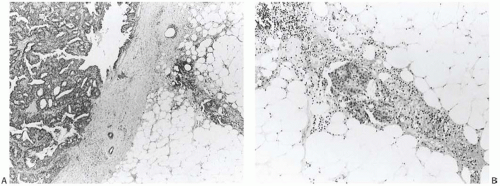

The gross appearance of papillary carcinomas varies considerably depending on the relative proportions of cystic and solid components (Fig. 14.1). The average clinically

determined size of tumors is 2 to 3 cm. Papillary carcinomas are usually well circumscribed grossly, and they may even appear encapsulated (Fig. 14.2). The tumor is soft to moderately firm, depending upon the extent of fibrosis. Bleeding into the tumor can impart a dark brown or hemorrhagic appearance, but the carcinomas are usually described as tan or gray. Needle aspiration or needle core biopsy can produce more hemorrhage than occurs in a nonpapillary mammary carcinoma because of the friable character of many papillary lesions, especially those without fibrosis or healed prior hemorrhage.

determined size of tumors is 2 to 3 cm. Papillary carcinomas are usually well circumscribed grossly, and they may even appear encapsulated (Fig. 14.2). The tumor is soft to moderately firm, depending upon the extent of fibrosis. Bleeding into the tumor can impart a dark brown or hemorrhagic appearance, but the carcinomas are usually described as tan or gray. Needle aspiration or needle core biopsy can produce more hemorrhage than occurs in a nonpapillary mammary carcinoma because of the friable character of many papillary lesions, especially those without fibrosis or healed prior hemorrhage.

MICROSCOPIC PATHOLOGY

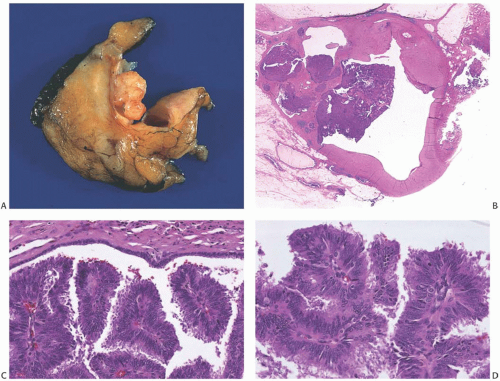

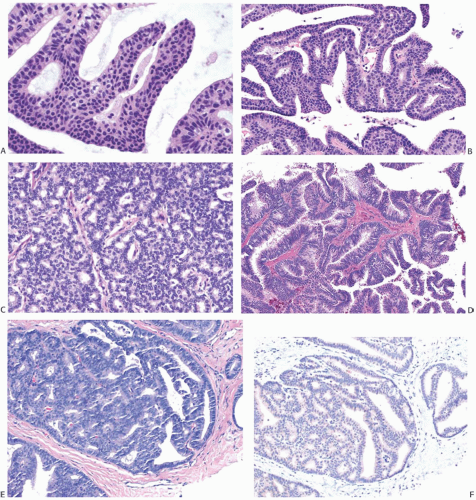

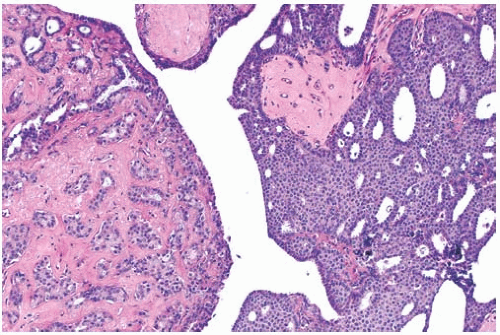

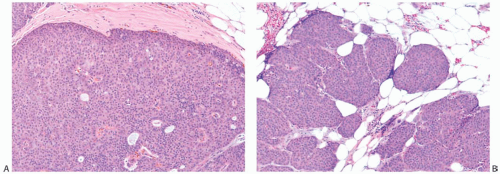

The term “papillary” describes carcinomas in which the underlying microscopic pattern is predominantly frond forming (Fig. 14.3). Although most of these tumors are large enough to form a palpable mass, the diagnosis is also applicable to microscopic lesions that have a papillary structure (Fig. 14.4). Many papillary carcinomas have cystic areas, but cyst formation is not necessary for the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma. Foote and Stewart14 observed that “in some areas the cell

proliferation becomes so dense that basic papillary properties are overgrown.” Such a tumor is classified as solid papillary carcinoma (Fig. 14.5). The underlying papillary nature of these lesions is defined by a branching network of fibrovascular stroma, but there are no spaces between individual papillary fronds.

proliferation becomes so dense that basic papillary properties are overgrown.” Such a tumor is classified as solid papillary carcinoma (Fig. 14.5). The underlying papillary nature of these lesions is defined by a branching network of fibrovascular stroma, but there are no spaces between individual papillary fronds.

NONINVASIVE PAPILLARY CARCINOMA

The histologic features of in situ papillary carcinomas contrast with those of their benign counterparts, papillomas. The distinction between the two lesions is determined by their cytologic and microscopic attributes. In 1962, Kraus and Neubecker36 set forth often quoted criteria for distinguishing benign from malignant papillary tumors. The histologic characteristics enumerated by Kraus and Neubecker are summarized in Table 14.1; however, numerous exceptions and structural variations complicate the application of these criteria.

The fundamental principle in evaluating papillary tumors is to determine whether the epithelium between adjacent fibrovascular cores has features diagnostic of DCIS. The space between the fibrovascular cores can be likened to a duct lumen bounded by these stromal elements and the epithelium covering the cores to the epithelium lining a duct. The cytologic and architectural attributes of the epithelial cells growing on the stromal cores determine that the nature of the papillary tumor and other, ancillary, findings will often help to substantiate the diagnosis.

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

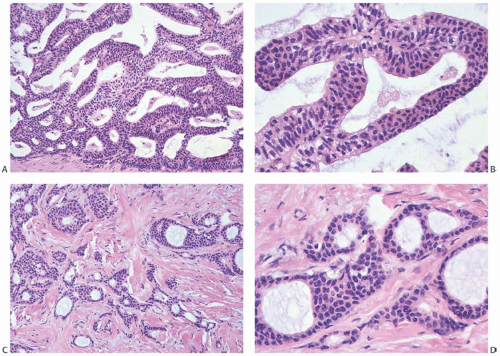

Cell Types

Benign luminal and myoepithelial cells make up the epithelium of a papilloma, whereas malignant ductal cells comprise the entire epithelial population of most papillary carcinomas. As a result of uneven stratification and loss of polarity with respect to stromal elements within the lesion (Fig. 14.6), the carcinoma cells of papillary carcinoma grow in a less orderly fashion than do the benign cells of papillomas. They usually do not form two consistently arranged layers composed of distinct cell types. Instead, the carcinoma cells demonstrate

papillary, micropapillary or filiform, cribriform, reticular, or solid growth patterns (Fig. 14.7).

papillary, micropapillary or filiform, cribriform, reticular, or solid growth patterns (Fig. 14.7).

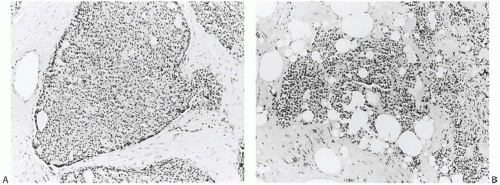

Myoepithelial cells that are distributed relatively uniformly and proportionately with the epithelium in benign papillary lesions are usually overgrown in papillary carcinomas. However, the finding of myoepithelial cells in some parts of a papillary lesion is not inconsistent with a diagnosis of carcinoma.37,38,39 Myoepithelial cells are prominent mainly in residual areas of a papilloma that has given rise to a papillary carcinoma, and they tend to be less conspicuous or absent in the carcinomatous areas (Fig. 14.8).

Nuclei

The malignant cells of papillary carcinomas demonstrate the same cytologic features as those of commonplace DCIS. Although the cellular attributes vary according to the grade of the carcinoma, common alterations include an increase in the size of the cell and enlargement of its nucleus. In common, low-grade papillary carcinomas, the cells appear uniform, but those of the uncommon high-grade papillary carcinomas demonstrate conspicuous cellular pleomorphism. The nuclei are characteristically hyperchromatic regardless of cytologic grade, and there is usually a high

nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. The mitotic figures vary in number, and they are more numerous in carcinomas that exhibit the most severe cytologic atypia. Mitotic activity is uncommon in papillomas. The presence of more than one mitosis in 10 high-magnification (40×) fields suggests the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma.

nuclear-to-cytoplasmic ratio. The mitotic figures vary in number, and they are more numerous in carcinomas that exhibit the most severe cytologic atypia. Mitotic activity is uncommon in papillomas. The presence of more than one mitosis in 10 high-magnification (40×) fields suggests the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma.

Apocrine Metaplasia

The tumor cells sometimes have secretory “snouts” at the luminal surface. The cytoplasm is typically amphophilic, but eosinophilic cells are found in a number of lesions. Papotti et al.37 found apocrine cells that were immunoreactive

for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 (GCDFP-15) in 75% of papillomas and in 50% of papillary carcinomas. Apocrine areas in a papillary carcinoma exhibit cytologic atypia consistent with the rest of the tumor and, in that way, differ from the bland foci of apocrine metaplasia commonly encountered in papillomas (Fig. 14.9). The presence of cytologically benign apocrine elements is invariably associated with a papilloma rather than a papillary carcinoma.

for gross cystic disease fluid protein-15 (GCDFP-15) in 75% of papillomas and in 50% of papillary carcinomas. Apocrine areas in a papillary carcinoma exhibit cytologic atypia consistent with the rest of the tumor and, in that way, differ from the bland foci of apocrine metaplasia commonly encountered in papillomas (Fig. 14.9). The presence of cytologically benign apocrine elements is invariably associated with a papilloma rather than a papillary carcinoma.

FIG. 14.8. Papillary carcinoma. A: Solid areas of carcinoma are distributed on the surfaces of the fronds of an underlying papilloma. B: Myoepithelial cells are seen in epithelium of the papilloma on the right, and they are absent in the papillary carcinoma on the left. C: Papillary carcinoma with cribriform structure and myoepithelial cells (arrows). D: Solid papillary carcinoma with spindle cell growth in which attenuated myoepithelial cells are highlighted by an immunostain for SMA. |

Glandular Pattern

Describing the epithelium of papillomas, Kraus and Neubecker36 introduced the term complex glandular pattern to refer to the compact, back-to-back arrangement of proliferative glands within the stalk of a papilloma. The authors noted that this close crowding of glands “… was often a source of confusion in that it superficially resembled the cribriform pattern of carcinoma.”36 The cribriform pattern characteristic of low-grade DCIS does occur in papillary carcinomas frequently. To distinguish the “complex glandular pattern” seen in papillomas from the cribriform spaces of papillary carcinoma, one should examine the tissue separating the individual acinar structures. Thin strands of collagen and slender capillaries surround each of the glands that compose the “complex glandular pattern,” whereas the spaces formed in cribriform carcinomas lack these connective stromal elements.

Stroma

Supporting fibrovascular stroma is present in virtually all papillary carcinomas, but it tends to be less conspicuous in carcinomas than in benign papillary lesions because of the dominance of the epithelial component in carcinomas. A minority of papillary carcinomas have areas in which there are relatively broad fibrous stalks of extensive sclerosis, and consequently the character of the stroma within the lesion is not by itself a reliable diagnostic feature (Fig. 14.10).

Scaring frequently occurs in the periphery of papillary tumors. This process can entrap both benign glands and those harboring in situ carcinoma. The resulting appearance simulates the look of invasive carcinoma and makes the recognition of minimal invasion difficult.

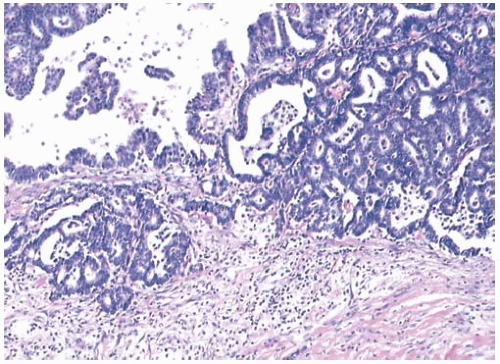

Adjacent Ducts

Carcinoma usually extends into ducts at the periphery of a papillary carcinoma. When the interpretation of an orderly papillary tumor is difficult, careful examination of the surrounding ducts can be extremely helpful. The presence of foci of papillary, cribriform, or comedocarcinoma is usually evidence that in situ carcinoma is also present in the papillary tumor. In the same way, study of an epithelial proliferation situated on the wall of the duct harboring a papillary tumor can shed light on the nature of the epithelial cells within the papillary portion.

Sclerosing Adenosis

In almost one-half of the papillomas studied by Kraus and Neubecker,36 the surrounding tissue displayed sclerosing adenosis (SA), and it protruded into ducts and simulated papillomas in a few instances. SA does not coexist with papillary carcinomas commonly.

FIG. 14.11. Papillary carcinoma with mucin secretion. A: Blue mucin vacuoles are present in the epithelium. B: The mucin is stained blue with the Alcian blue/PAS reaction. |

Mucin Secretion

There is a broad range of mucin secretion demonstrable in papillary carcinomas with the mucicarmine, Alcian blue, and periodic acid-Schiff (PAS) stains (Fig. 14.11). Some papillary carcinomas have no detectable intracellular mucin. In the majority, mucin secretion is not prominent, but a small number of papillary carcinomas have signet ring cells (Fig. 14.12) or abundant and diffuse intracellular mucin secretion (Fig. 14.13). The accumulation of abundant extracellular mucin creates a pattern that resembles invasive mucinous carcinoma, but does not represent invasion when confined within the tumor (Fig. 14.14).

Microcalcifications

Microcalcifications found in many papillary carcinomas are usually distributed in the glandular portions of the lesion, but they may also be found in the papillary stroma. Calcifications also form in the stroma of papillomas, so neither the presence nor the pattern of calcification provides reliable diagnostic information.

Residual Papilloma

Papillary carcinoma that has arisen in a papilloma sometimes retains areas of papilloma that appear benign or atypical, as well as having foci of more cellular proliferation diagnostic of carcinoma (Figs. 14.8, 14.9, and 14.15). Small areas of papilloma in such lesions are of little consequence, and they should not impede the recognition of the carcinomatous element. In some instances, the diagnosis of papillary carcinoma can be “a ‘shadow land’ even for the most experienced pathologist,”40 a situation that Foote and Stewart14 referred to as “a zone of altered cell growth where the diagnosis of carcinoma versus atypical papillomatosis

is a question of occult distinction and must be accepted or rejected on grounds of faith in the pathologist or lack of it.” “Borderline” papillary lesions that fit this description often have modest or substantial areas of benign papillary proliferation as well as more cellular and atypical components. To make a diagnosis of carcinoma in the latter setting, it is necessary to find one or more low-power microscopic fields where the growth pattern and cytologic appearance constitute one of the established patterns of DCIS. Some authors have illustrated focal DCIS in papillomas, but classified these lesions as “papillomas with atypical ductal hyperplasia.”41,42 In one of these studies, the relative risk for “subsequent carcinoma” in women with such papillomas was more than four times the risk of women with papillomas that lacked atypical ductal hyperplasia/DCIS.42 Underdiagnosis of such lesions is likely to result in inadequate treatment that is reflected in the outcomes of patients in these reports.

is a question of occult distinction and must be accepted or rejected on grounds of faith in the pathologist or lack of it.” “Borderline” papillary lesions that fit this description often have modest or substantial areas of benign papillary proliferation as well as more cellular and atypical components. To make a diagnosis of carcinoma in the latter setting, it is necessary to find one or more low-power microscopic fields where the growth pattern and cytologic appearance constitute one of the established patterns of DCIS. Some authors have illustrated focal DCIS in papillomas, but classified these lesions as “papillomas with atypical ductal hyperplasia.”41,42 In one of these studies, the relative risk for “subsequent carcinoma” in women with such papillomas was more than four times the risk of women with papillomas that lacked atypical ductal hyperplasia/DCIS.42 Underdiagnosis of such lesions is likely to result in inadequate treatment that is reflected in the outcomes of patients in these reports.

Three-Dimensional Structure

Three-dimensional reconstruction of the microscopic structure of papillary lesions has revealed some interesting differences between papillomas and papillary carcinomas.43,44 In papillomas and usual ductal hyperplasia (UDH), the luminal spaces between the proliferating epithelial cells form a complex but diffusely anastomosing continuous network of channels. On the other hand, in DCIS, the luminal spaces tend to be separate, and they do not form a continuous network. These elegant and painstaking studies have resulted in a more complete appreciation of the structural differences between hyperplastic and carcinomatous papillary lesions.

Cystic Papillary Fluid

In additional to histologic study, biochemical analysis of the fluid from cystic papillary lesions may be helpful in the differential diagnosis between cystic papilloma and papillary carcinoma. Matsuo et al.45 found an elevated carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) content in aspirated fluid from a 10-cm cystic breast tumor. CEA was demonstrated immunohistochemically in the carcinoma cells in the resected specimen. Another study compared CEA and human epidermal growth factor 2 (HER2) protein levels in fluid from 6 cystic papillomas, 6 papillary carcinomas, and 42 gross cysts.46 Five of the six carcinomas (83%) had elevated levels of both proteins compared with two (33%) of the papillomas and two (5%) of gross cysts.

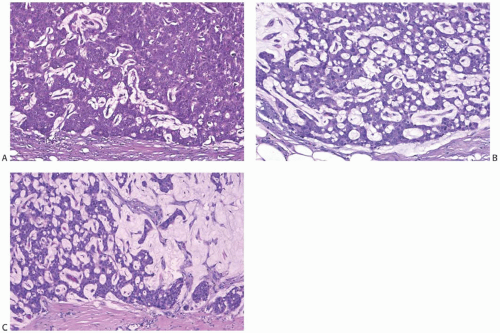

INVASIVE PAPILLARY CARCINOMA

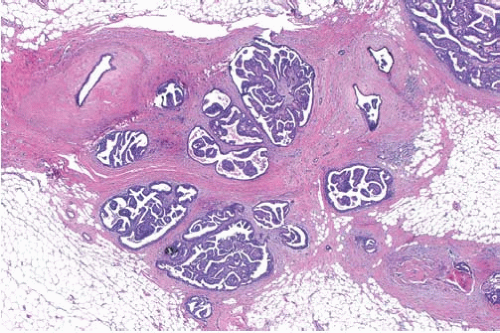

Evidence of Invasion

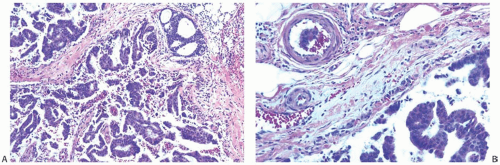

The growth patterns found in areas of frankly invasive papillary carcinoma usually constitute variations on the architecture of the carcinoma in the underlying in situ papillary tumor (Fig. 14.16). The cytologic characteristics of the invasive component also resemble those of the in situ portion of the lesion, in some cases including apocrine features. Cribriform, comedo, tubular, and mucinous foci may also be present. The invasive element may grow partly or entirely as mucinous

carcinoma, an occurrence usually associated with solid papillary carcinoma. Mucinous differentiation in solid papillary carcinoma is manifest not only by the presence of intracellular and intraluminal mucin but also by the accumulation of extracellular mucin in limited amounts between the neoplastic epithelium and adjacent stroma (Fig. 14.14). This phenomenon can occur within the tumor, adjacent to fibrovascular stalks, and at the border of the tumor. The resultant small pools of mucin are not interpreted as invasive mucinous carcinoma unless they contain detached neoplastic cells. Larger accumulations may surround or disrupt portions of the epithelium, and the resultant appearance is interpreted as invasive mucinous carcinoma when carcinoma cells surrounded by mucin extend into the adjacent stroma (Fig. 14.17).

carcinoma, an occurrence usually associated with solid papillary carcinoma. Mucinous differentiation in solid papillary carcinoma is manifest not only by the presence of intracellular and intraluminal mucin but also by the accumulation of extracellular mucin in limited amounts between the neoplastic epithelium and adjacent stroma (Fig. 14.14). This phenomenon can occur within the tumor, adjacent to fibrovascular stalks, and at the border of the tumor. The resultant small pools of mucin are not interpreted as invasive mucinous carcinoma unless they contain detached neoplastic cells. Larger accumulations may surround or disrupt portions of the epithelium, and the resultant appearance is interpreted as invasive mucinous carcinoma when carcinoma cells surrounded by mucin extend into the adjacent stroma (Fig. 14.17).

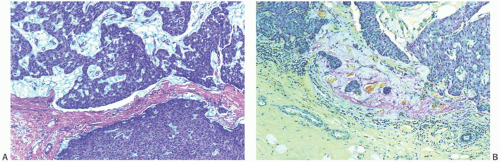

FIG. 14.17. Papillary carcinoma, invasive mucinous. A: Extracellular mucin in a solid papillary carcinoma confined to the tumor (above) does not constitute invasive carcinoma (see Fig. 14.14). B: Small clusters of carcinoma cells and mucin in the peritumoral stroma represent invasive mucinous carcinoma (mucicarmine stain). |

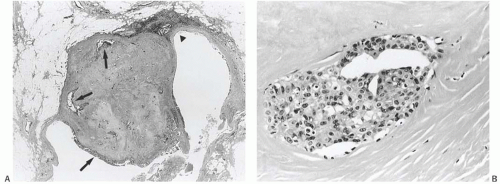

Clusters of invasive papillary carcinoma cells are particularly prone to shrinkage artifact, and they often appear to lie in spaces, creating the appearance of lymphatic tumor emboli. When one applies strict criteria for the diagnosis of lymphatic invasion, most such foci prove to be artifactual.47

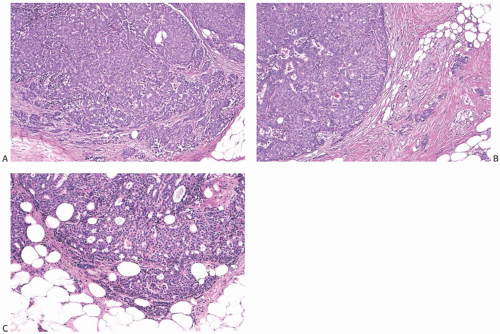

The invasive nature of many papillary carcinomas appears obvious, but the recognition of minimally invasive papillary carcinoma can be difficult. Many papillary carcinomas are bounded by zones of fibrosis, recent or resolved hemorrhage, and chronic inflammation, and similar alterations may occur within the lesion. Papillary or glandular clusters of epithelial cells routinely found within these areas present a challenging problem (Fig. 14.18). If one recalls that similar patterns of epithelial dispersal can occur in sclerotic portions of benign papillary lesions, it is possible to determine that these do not constitute foci of invasion in most cases. Groups of neoplastic cells distributed parallel to layers of reactive stroma at the border of a papillary carcinoma usually represent entrapped in situ epithelium rather than invasive carcinoma. An actin immunostain is sometimes helpful in this situation, although staining of reactive myofibroblasts can complicate the interpretation. Myofibroblastic staining is avoided if the p63 immunostain is used, but this procedure is useful only if the p63 stain reveals myoepithelium throughout the papillary tumor. Isolated invasive carcinoma cells can be identified with a cytokeratin immunostain. In general, the most reliable histologic evidence of frank invasion is extension of tumor beyond the zone of reactive changes into the mammary parenchyma and fat (Figs. 14.17, 14.19, and 14.20).

Effects of Needling Procedures

Papillary lesions that have been subjected to fine-needle aspiration (FNA) or needle core biopsy prior to excision can exhibit iatrogenic alterations that complicate the determination of invasion. Hemorrhage is commonly found in and around the tumor grossly. The best microscopic clues to such manipulation of the tumor are the presence of fresh

hemorrhage and acute inflammation associated with “unnatural” fragmentation of the lesion. Tumor cells can be found singly or in clusters deposited in areas of hemorrhage and along the course of the needle tracks (Fig. 14.21). As long as it is known that the lesion was recently biopsied, these detached cells are best regarded as the result of trauma rather than as evidence of invasion. Sometimes epithelial cells are also seen in capillary or lymphatic channels after needle aspiration (Fig. 14.22). This uncommon finding should be described in the pathology report and may be regarded as a manifestation of invasive carcinoma in some instances.48 Epithelial displacement associated with needling procedures is discussed more extensively in Chapter 44.

hemorrhage and acute inflammation associated with “unnatural” fragmentation of the lesion. Tumor cells can be found singly or in clusters deposited in areas of hemorrhage and along the course of the needle tracks (Fig. 14.21). As long as it is known that the lesion was recently biopsied, these detached cells are best regarded as the result of trauma rather than as evidence of invasion. Sometimes epithelial cells are also seen in capillary or lymphatic channels after needle aspiration (Fig. 14.22). This uncommon finding should be described in the pathology report and may be regarded as a manifestation of invasive carcinoma in some instances.48 Epithelial displacement associated with needling procedures is discussed more extensively in Chapter 44.

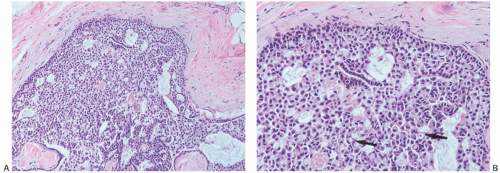

FIG. 14.20. Papillary carcinoma, microinvasive. Isolated microinvasive carcinoma cells are highlighted in the peritumoral stroma by a cytokeratin immunostain (CAM5.2). |

One unusual pattern of true invasion found in solid papillary carcinomas simulates epithelial displacement resulting from needling procedures. This type of invasion is characterized by the presence of one or more irregular cohesive sheets of carcinoma cells in fat or stroma surrounding the tumor without the reactive stromal changes that ordinarily accompany invasive carcinoma (Fig. 14.23). These invasive carcinomatous foci abut sharply on normal fat cells or less often on collagenous stroma in a fashion that superficially suggests that they were “pushed” or artifactually displaced to this location. In this situation, the features that favor true invasion are the absence at this site of evidence of a prior procedure such as hemorrhage, fat necrosis, a needle track, or tissue disruption. Perhaps the most telling observation is the intimate mingling of carcinoma cells and normal tissue, especially in fat, where individual adipose cells may be found in the sheet of carcinoma cells. Carcinoma cells may be “molded” around fat cells within or at the border of such foci (Fig. 14.24).

FIG. 14.22. Papillary carcinoma, needle biopsy. A: Tumor disruption and hemorrhage. B: Disrupted papillary neoplasm (below) and a fragment of papillary epithelium in a blood vessel (above). |

VARIANT PATTERNS OF PAPILLARY CARCINOMA

Classical invasive papillary carcinomas consist of a population of malignant ductal cells forming a more or less compact mass and dissecting into the surrounding tissue in an arborizing manner. Differences in the manner of growth or the characteristics of the neoplastic cells give rise to several variant patterns of in situ and invasive papillary carcinoma.

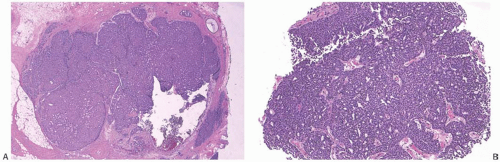

(Intra)cystic Papillary Carcinoma

Physicians have known of the existence of predominantly cystic papillary carcinomas since the middle of the 19th century, but the lesion did not become well defined until 100 years later, when Gatchell et al.49 and Czernobilsky50 published studies of cases from the Mayo Clinic and the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, respectively. Czernobilsky described the features of this form of papillary carcinoma as “… a large, usually solitary hemorrhagic cyst surrounded by a fibrous wall into which projects a predominantly papillary adenocarcinoma which often also lines the inner surface of the cyst and the absence of extensive tumor involvement of the tissues surrounding the cyst favor the diagnosis of intracystic carcinoma.” In both reports, this form of carcinoma constituted 0.5% of mammary carcinomas; however, a subsequent study by McKittrick et al.51 reported a frequency of 2.0%, and among a large group of Swedish and Hungarian women,52 intracystic papillary carcinoma accounted for 1.3% of breast carcinomas.

The age of patients with cystic papillary carcinoma ranges from 2149 to 94 years,51 and the lesion affects both women and men. Cases in men have attracted special interest,53,54,55,56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65 and one notes the large proportion of reports in the Japanese literature.56 In one series,66 intracystic papillary carcinoma accounted for 5% of breast carcinoma in men. The ages of men with cystic papillary carcinoma cluster in the seventh and eighth decades with just a few cases beyond the age of 80 years.55 Patients usually report especially long symptomatic intervals. In one case,67 the patient noted the appearance of the mass 10 years prior to presentation, and in another, complaints persisted for 59 years before the patient sought medical attention.49

Most cystic papillary carcinomas appear well defined on a mammogram,55,58,60,68 but two cases displayed slightly ill-defined margins,62 and two others appeared lobulated.30,59 Calcifications occur in only a minority of cases.62 The calcifications appear linear, amorphous, or stippled. Ultrasonography reveals a complex, predominantly cystic mass with posterior enhancement and one or more mural nodules. Serial studies of one case demonstrated growth of the nodule.55 Intracystic carcinomas usually consist of just one cyst, but multilocular examples have been described.29,53,58,64,68 Computerized tomography scans reveal the cyst69 and may show an inner mass.64 MRI has the ability to demonstrate both the cystic and the solid components,29,58,63 and it can highlight regions of invasion.29 Dynamic MRI studies may yield findings that suggest a malignant neoplasm.63,70 Pneumocystography highlights the intracystic tumor and thickening of the cyst wall.52,53

Classical cystic carcinomas present a characteristic macroscopic appearance. They usually measure several centimeters; however, dimensions as large as 18 cm have been recorded,67

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree