Pancreatic Endocrine Tumors

Jeffrey A. Norton

Yijun Chen

Pancreatic endocrine tumors (PETs) are rare pancreatic neoplasms with an annual incidence of 1 to 1.5 per 100,000 population, resulting in approximately 2,500 cases per year in the United States. They account for 1% to 2% of all pancreatic neoplasms. PETs are clinically classified into two groups: functional and nonfunctional. Functional PETs secrete biologically active peptides causing one of the previously well-described syndromes including insulinoma, gastrinoma, VIPoma, glucagonoma, somatostatinoma, and other exceedingly rare neoplasms. Nonfunctional PETs are not associated with a specific hormonal syndrome. They account for 15% to 30% of all PETs. Insulinoma is the most common islet cell tumor, while gastrinoma and pancreatic polypeptide (PP)-oma are the most common malignant islet tumor. With the exception of insulinomas, that is usually benign, most PETs are potentially malignant. However, although many of the PETs are malignant, they usually have slow growth and aggressive surgical resection should benefit most patients. Data from many centers and the National Cancer Data Base have demonstrated that surgical resection of primary tumor and metastases in patients with PETs is associated with improved survival.

The majority of PETs are sporadic, but PETs may also be associated with genetic syndromes such as MEN-1 (5% to 10% of patients), von Hippel–Lindau (VHL) disease, neurofibromatosis 1 (NF-1), and tuberous sclerosis (TSC). Most authors believe that the cells of PETs are from the embryonic endodermal cells that later give rise to the islet cells of Langerhans. It is important to differentiate PETs from exocrine tumors of pancreas (pancreatic adenocarcinomas), because PETs have a much better prognosis. From the National Cancer Data Base, for 3,851 patients who underwent surgical resection of PETs, the 5-year overall survival was 59.3%, and the 10-year survival was 37.7%. However, the 5-year survival for similar patients with pancreatic adenocarcinoma is generally between 5% and 20%.

There are several important general principles in managing patients with PETs. Unequivocal biochemical diagnosis for suspected hormonal syndrome should be established. Further, every patient should be carefully assessed for family history of endocrine tumors, especially MEN-1. For endocrinally functional tumors, control of the hormonal syndrome should be done to prepare the patient for surgery. When planning surgical treatment, complete extirpation of tumor should be the goal, but it must be tailored to the severity and natural course of the disease, the general condition of the patient, and the possible complications.

Insulinoma

The incidence of insulinoma is approximately 0.5 to 1 in a million population. They account for about 30% to 45% of all functional PETs. They are the most common functional PET. Insulinomas are generally solitary, except in MEN-1 when they may be multiple throughout the pancreas. About 90% of insulinomas are benign. They are small and uniformly distributed.

Patients with insulinoma usually present with symptoms related to episodic hypoglycemia caused by uncontrolled secretion of insulin. Common symptoms are neuroglycopenic (personality changes, blurred vision, fatigue, and seizures) and neurogenic (hunger, sweating, anxiety, tremor, and palpitations due to activation of the autonomic nervous system). Symptoms commonly occur during the early morning hours, when glucose reserves are low after a period of overnight fasting and tumor insulin production remains elevated. Symptoms may also occur during exercise when glycogen stores are low.

The majority (60% to 75%) of patients are women and some may have undergone extensive psychiatric evaluation. Delay in diagnosis is common. Because insulinoma is rare and neuroglycopenic symptoms are relatively nonspecific, a high index of suspicion for insulinoma is necessary when other explanations for these symptoms are not evident.

In the workup of a patient with any PET, multiple endocrine neoplasia type 1 (MEN-1) must be excluded. This should be done by carefully checking family history of manifestations of MEN-1 (prolactinoma, primary hyperparathyroidism, low blood glucose, secretory diarrhea, PET, kidney stone, and multiple lipomas seen on physical examination). Biochemical studies to exclude other MEN-1 tumors should be done when there is suspicion of prolactin, ionized calcium, parathyroid hormone (PTH), gastrin, and PP. In any patient with the possibility of MEN-1, the MEN-1 gene can be sequenced.

The Whipple’s triad consists of symptoms of hypoglycemia during a fast, a concomitant blood glucose concentration less than 45 mg/dL, and relief of the hypoglycemic symptoms after glucose administration. The diagnosis of insulinoma is made by the presence of low blood glucose levels (<45 mg/dL) and falsely elevated serum insulin levels (>5 μU/mL). Factitious or surreptitious hypoglycemia must be excluded. The 72-hour fast is the gold standard for diagnosis of insulinoma. It is done in the hospital with appropriate biochemical measurements and close observation. During this test, patients should have intravenous (IV) access, and are allowed to have only noncaloric liquids. The fast may last as long as 72 hours, although most patients develop symptoms in 24 hours. Neuroglycopenic symptoms (confusion, slurred speech, and visual changes) mark the end of the fast. Serum glucose and insulin concentrations are measured every 6 hours and when the patient develops neuroglycopenic symptoms. The fast is concluded when the patient has symptoms and the plasma glucose level drops to less than 45 mg/dL. At that time, blood insulin levels, C-peptide levels, and proinsulin levels are measured and glucose is administered. Urine sulfonylurea products levels are also checked to exclude administration of oral hypoglycemic drugs. The patient is given IV glucose to relieve symptoms. A positive test is defined as hypoglycemia (45 mg/dL) with elevated insulin levels (>5 μU/mL). Some tumors make large amounts of proinsulin (>25%) that do not lower blood glucose level as much as regular insulin. Insulinoma patients should also have elevated C-peptide levels.

In the pediatric population, insulinoma must be distinguished from nesidioblastosis, a congenital islet cell dysmaturation, or malregulation that occurs primarily in infants and causes hyperinsulinemic hypoglycemia. Age at the time of presentation is the most important distinguishing factor, as nesidioblastosis occurs most commonly in children under the age of 18 months. Approximately half of infants with nesidioblastosis require a spleen-preserving near-total pancreatectomy, in which 95% of the pancreas is removed, because this disorder affects the entire pancreas diffusely. Some have been successfully managed with octreotide, and patients outgrow hypoglycemia. Adult nesidioblastosis is very infrequent. Hypoglycemia has been associated with gastric bypass surgery, but this can usually be managed with octreotide instead of pancreatectomy.

Localization of Insulinoma

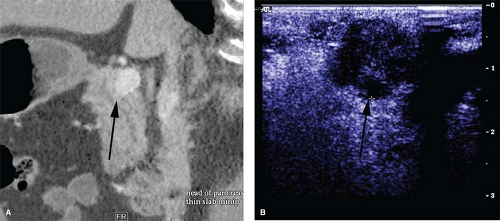

Since insulinomas are small, accurate preoperative and intraoperative tumor localization is critical. Modern radiologic imaging facilitates the localization of the tumor, avoiding the need for a “blind” pancreatic resection. Computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) are able to identify pancreatic tumors as small as 1 cm in diameter. Pancreatic protocol CT with arterial contrast and thin cuts is our imaging modality of choice. However, the sensitivity of CT is the same as that of MRI. Few false positives occur. Somatostatin-receptor scintigraphy (SRS), which has a major role in imaging other PETs, is not useful in locating insulinomas, as they have a low density of somatostatin subtype-2 cell-surface receptor.

Since about 20% to 50% of patients have small (<2 cm) insulinomas that are not detected by noninvasive imaging, a few more sensitive invasive tests have evolved to localize these tumors preoperatively. Endoscopic ultrasound (EUS) uses a high-frequency ultrasound probe (5 to 10 mHz) that is placed endoscopically in close proximity to the pancreas. The pancreatic head and duodenum are scanned with the probe positioned in the duodenum. The body and tail are imaged through the stomach. EUS may be the best preoperative imaging study to localize the insulinoma. The detection rate is highest in the head of the pancreas (83% to 100%) because the head can be viewed from three angles (from the third portion of the duodenum, through the bulb of the duodenum, and through the stomach). It is lower (37% to 60%) in the body and tail, which can only be viewed through the stomach. However, false positives may occur, especially with accessory spleens. It is best to ask for an EUS-guided biopsy. If that is positive, it is unequivocal.

If both noninvasive imaging and EUS fail to localize the tumor, calcium arteriography can be used. The calcium arteriogram has largely replaced portal venous sampling (PVS). It is the most informative preoperative test for localizing occult insulinomas. Arteries that perfuse the pancreatic head (gastroduodenal artery and superior mesenteric artery) and the body/tail (splenic artery) are selectively catheterized sequentially, and a small amount of calcium gluconate (0.025 mEq Ca2+/kg bodyweight) is injected into each artery during different runs. A catheter positioned in the right hepatic vein is used to collect blood for measurement of insulin concentrations. A positive result requires twofold increase in the hepatic vein insulin concentration. It localizes the tumor to the area of the pancreas being perfused by the injected artery. In this way, calcium arteriography helps to identify the region of the pancreas containing the tumor (head, body, or tail). The arteriogram portion of the study may also show the tumor as a vascular blush. The sensitivity of calcium angiogram is between 88% and 94%. If during surgical exploration, palpation and ultrasound fail to identify the tumor, calcium angiogram–guided resection may be indicated. However, recently, with improved localization methods, the utilization of this study has declined.

For patients who have clear clinical and biochemical evidence for insulinoma, but extensive preoperative workup fails to

localize the tumor, surgical exploration is still indicated. Studies have demonstrated that even in this situation most patients will have successful surgery. The single best modality for localizing insulinoma is intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) (>95%). Surgical exploration with exposure and palpation of the pancreas combined with the use of IOUS is accepted as the most cost-effective approach for primary insulinomas, even when other preoperative studies are negative.

localize the tumor, surgical exploration is still indicated. Studies have demonstrated that even in this situation most patients will have successful surgery. The single best modality for localizing insulinoma is intraoperative ultrasound (IOUS) (>95%). Surgical exploration with exposure and palpation of the pancreas combined with the use of IOUS is accepted as the most cost-effective approach for primary insulinomas, even when other preoperative studies are negative.

Medical Management of Hypoglycemia

The aim of medical management is to avoid life-threatening hypoglycemia. Euglycemia is maintained initially with frequent feeds of a high-carbohydrate diet, including a night meal. Cornstarch may be added to food for prolonged absorption. Diazoxide, which inhibits insulin release, is used for patients who continue to become hypoglycemic between feedings. Diazoxide should be discontinued 1 week prior to surgery to avoid intraoperative hypotension. Calcium-channel blockers or phenytoin may also suppress insulin production in some patients.

Operative Management

Surgery is the only curative therapy for insulinoma. With the use of IOUS, blind pancreatic resection is no longer indicated. Enucleation is indicated for most small and benign tumors that are less than 2 cm. Preoperative localized tumors can be removed with laparoscopic techniques. The gold standard of tumor localization is IOUS and palpation. Even in occult insulinoma patients, adequate mobilization of the pancreas with the use of IOUS results in successful identification and resection of the insulinoma in nearly all cases.

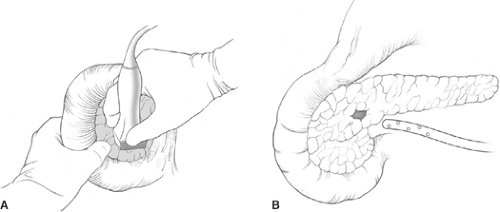

Laparoscopic approaches to insulinoma should be done for well-localized solitary tumors. In general, a 30-degree camera is used and four ports are placed. The specific area of the pancreas with tumor is exposed by either doing a Kocher maneuver or opening the gastrocolic ligament. IOUS is used to identify the tumor and guide the dissection. The relationship of the tumor to vital structures like the superior mesenteric vein (SMV), portal vein, common bile duct, and pancreatic duct is clarified with ultrasound. Tumors in the head and body are enucleated with ultrasound guidance using the harmonic scalpel. Tumors in tail are resected using an endo-stapler. The spleen should be preserved if possible. After tumor removal, a frozen section of PET is performed and blood glucose levels usually increase. Fibrin glue sealant and a closed-suction drains are used to control pancreatic exocrine secretion. Laparoscopic removal of insulinoma with enucleation or distal pancreatectomy has been applied in many centers, and has been associated with markedly reduced hospital stay, reduced pain, and smaller incisions.

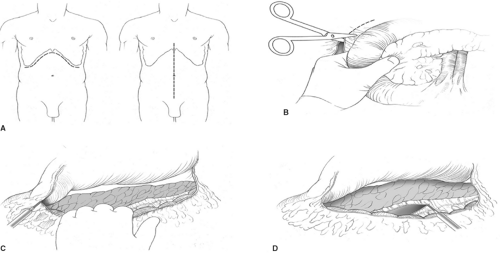

For open procedures, bilateral subcostal incision is recommended to give adequate exposure of the pancreas. Access to the pancreas is most typically gained through the lesser sac by dividing the gastrocolic omentum. An extended Kocher maneuver of the duodenum is done to lift the head of the pancreas out of the retroperitoneum. The separation of the transverse mesocolon from the inferior border of the pancreas allows for complete mobilization of the pancreas (Fig. 1). Since almost all insulinomas are located within the pancreas and are uniformly distributed throughout the entire gland, the entire pancreas should be visually inspected and bimanually palpated to identify the presence of tumors after complete mobilization. Insulinomas are

typically small, solitary, encapsulated, and reddish-brown. The tumor feels like a firm, nodular, and discrete mass. Approximately 65% of insulinomas may be identified by the traditional operative maneuvers of inspection and palpation. IOUS is critical during surgery for insulinomas because it not only facilitates identification of these tumors, but also helps to define the relationship of the tumor to the common bile duct, pancreatic duct, portal vein, and adjacent blood vessels. On IOUS, an insulinoma appears as a sonolucent mass with margins distinct from the uniform, more echodense pancreatic parenchyma (Fig. 2). In experienced hands, the sensitivity for detecting insulinomas using IOUS is approximately 95%.

typically small, solitary, encapsulated, and reddish-brown. The tumor feels like a firm, nodular, and discrete mass. Approximately 65% of insulinomas may be identified by the traditional operative maneuvers of inspection and palpation. IOUS is critical during surgery for insulinomas because it not only facilitates identification of these tumors, but also helps to define the relationship of the tumor to the common bile duct, pancreatic duct, portal vein, and adjacent blood vessels. On IOUS, an insulinoma appears as a sonolucent mass with margins distinct from the uniform, more echodense pancreatic parenchyma (Fig. 2). In experienced hands, the sensitivity for detecting insulinomas using IOUS is approximately 95%.

Most insulinomas are amenable to enucleation, which excise only the adenoma with minimal normal pancreatic tissue loss. Tumor size, location, and surrounding anatomy determine whether enucleation or pancreatic resection is performed. IOUS allows a precise, safe tumor enucleation and helps plan the shortest, most direct route to the tumor while avoiding the pancreatic duct (Fig. 3). The indication for distal or subtotal pancreatectomy includes large tumors, malignant tumors, proximity to the ductal structure, and the inability to get a clear margin between normal pancreas and the tumor. In rare cases, pancreaticoduodenectomy is indicated if enucleation cannot be performed safely. About 10% insulinoma patients have MEN-1, and a more aggressive approach is warranted in those patients. Most have multiple pancreatic tumors throughout the pancreas and thus may require a distal pancreatectomy and enucleation of any palpable or ultrasonographically detected lesions in the head of the gland. The goal of surgery is to ameliorate the hypoglycemia by eliminating the source of insulin. Usually a dominant large tumor (>3 cm) is responsible for secreting the excessive insulin.

For patients with malignant insulinoma, the procedure should be planned to attempt to remove all tumors. This may require major pancreatic resection and/or combined liver resection. Radiofrequency ablation (RFA) can also be used to eliminate unresectable lesions in the liver. If most of the insulin-producing tumor can be removed, then this will benefit the patient in terms of long-term symptomatic control of the glucose level.

Outcome

Most patients with sporadic insulinoma are cured of hypoglycemia. They have a normal long-term survival. However, for MEN-1 patients, persistent or recurrent hypoglycemia owing to multiple insulinomas or metastatic tumor is not uncommon. With the use of IOUS, the pancreatic surgery for insulinoma should have a low morbidity and mortality rate. Potential complications include fistula, pseudocyst, pancreatitis, and abscess.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree