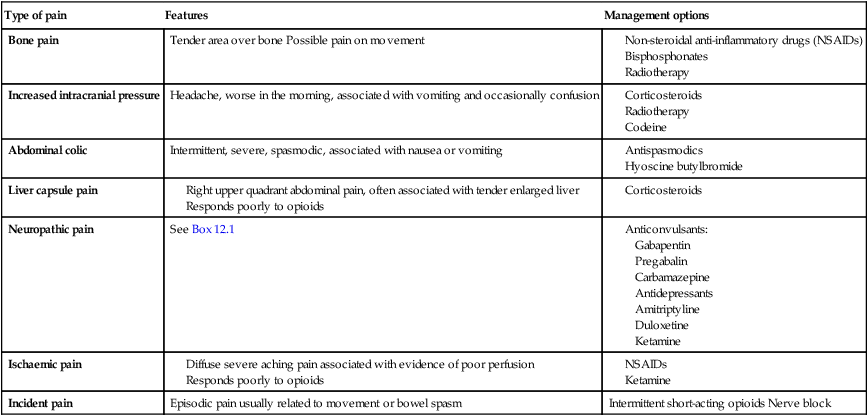

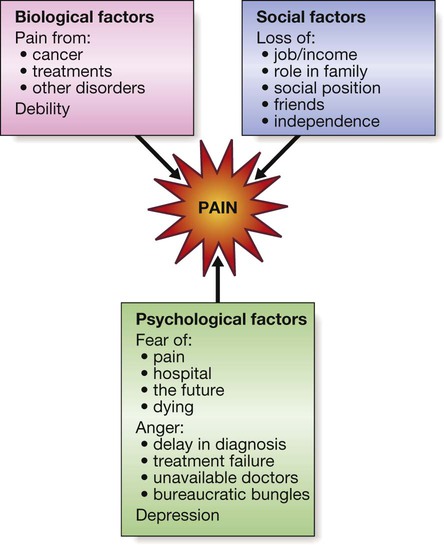

Pain can be classified into two types: • Nociceptive: due to direct stimulation of peripheral nerve endings by a noxious stimulus such as trauma, burns or ischaemia. • Neuropathic: due to dysfunction of the pain perception system within the peripheral or central nervous system as a result of injury, disease or surgical damage, such as continuing pain experienced from a limb which has been amputated (phantom limb pain). This should be identified early (Box 12.1) because it is more difficult to treat once established. The pain perception system (p. 1147) is not a simple hard-wired circuit of nerves connecting tissue pain receptors to the brain, but a dynamic system in which a continuing pain stimulus can cause central changes that lead to an increase in pain perception. This plasticity (changeability) applies to all the peripheral and central components of the pain pathway. Early and appropriate treatment of pain reduces the potential for chronic undesirable changes to develop. Accurate assessment of the patient is the first step in providing good analgesia. A full pain history should be taken, to establish its causes and the underlying diagnoses. Patients may have more than one pain; for example, bone and neuropathic pain may both arise from skeletal metastases (Box 12.2). • Verbal rating scale. Different verbal descriptions are used to rate pain – ‘no pain’, ‘mild pain’, ‘moderate pain’ and ‘severe pain’. • Visual analogue scale. A question is used, such as ‘Over the past 24 hours, how would you rate your pain, if 0 is no pain and 10 is the worst pain you could imagine?’ • Behavioural rating scale. It can be particularly difficult to decide whether a patient with cognitive impairment is suffering pain. A variety of measures are available which use observed behaviours, such as agitation and withdrawn posture, to assess levels of pain. Commonly used scales include Abbey and Dolorplus. Changes in behavioural rating pain scores can indicate whether drug measures have been successful. Perception of pain is influenced by many factors other than the painful stimulus, and pain cannot therefore be easily classified as wholly physical or psychogenic in any individual (Fig. 12.2). Patients who suffer chronic pain will be affected emotionally and, conversely, emotional distress can exacerbate physical pain (p. 240). Full assessment for symptoms of anxiety and depression is essential to effective pain management. Two-thirds of patients with cancer experience moderate or severe pain, and a quarter will have three or more different pains. Many of these are of mixed aetiology and 50% of pain from cancer has a neuropathic element. Careful evaluation to identify the likely pain mechanism facilitates appropriate treatment (see Box 12.2). It is vital that the patient’s concerns about opioids are explored. Patients should be reassured that, when they are used for pain, psychological dependence and tolerance are extremely rare (Box 12.3).

Palliative care and pain

Presenting problems in palliative care

Pain

Pain classification and mechanisms

Assessment and measurement of pain

History and measurement of pain

Psychological aspects of chronic pain

Management of pain

Palliative care and pain