15 Palliative and supportive care

Defining palliative and supportive care

Supportive care helps patients and their families to cope with cancer and its treatment – through the process of diagnosis and treatment, to continuing illness, possible cure or death and into bereavement. (NICE 2004). Where cure is not an option, care is focused on helping them through the difficult times ahead and maintaining optimum independence with the best quality of life possible. Supportive care is an integral part of palliative care.

Palliative care involves the total care of patients with advanced progressive illness which no longer responds to curative treatment. It is needed when the best quality of life for them and their families becomes the most important issue, and where the management of pain and other symptoms, and the provision of psychological, social and spiritual support, are paramount. Palliative care neither hastens nor postpones death: it merely recognizes a patient’s right to spend as much time as possible at home, and pays equal attention to physical, psychological, social and spiritual aspects of care wherever the patient is (World Health Organization [WHO] 1990).

• remain in reasonable good health until shortly before death, with a steep decline in the last few weeks or months

• decline more gradually, with episodes of acute ill health

• be very frail for months or years before death with a steady, progressive decline

(Department of Health [DOH] 2008 End of Life Care Strategy).

Palliative and supportive care requires the expertise of a multidisciplinary team whose members include doctors, nurses, physiotherapists, occupational therapists, social workers, clergy, counsellors, complementary therapists etc., but to be effective it must be tailored to the needs of patients and their families. Often both palliative and supportive care are provided by the patient’s family and other carers, and not exclusively by professionals (NICE 2004). The aromatherapist, even if treating a patient independently, is still part of the team and should recognize the importance of keeping the team informed of his/her part in the patient’s care.

The disorders involved

Until now, palliative and supportive care has been largely confined to those with cancer – at least 50% of all patients in the UK with this condition will have had such care at some time in the course of their illness (Addington-Hall 1998). However, in developed countries more people die of chronic circulatory and respiratory conditions such as chronic heart disease (CHD), stroke and chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD). Few palliative care services have focused on their needs or those of others with non-cancerous life-limiting conditions when they near the end of their life (NICE 2003; Ahmedzai 2006; Gore et al. 2000).

The ageing population is increasing rapidly – it is estimated that by 2033 in the UK, 23% of the population will be over the age of 65 (Office of National Statistics 2009). Many, if not most, will have two or more coexisting chronic conditions that will significantly impair their quality of life. Palliative and supportive care has now broadened to include all those with life-limiting conditions, notably:

• infection with human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) and acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS)

• degenerative neurological disorders such as motor neuron disease (MND), multiple sclerosis (MS) and Parkinson’s disease (PD)

• chronic circulatory conditions, including CHD and stroke

• chronic respiratory conditions, e.g. COPD

• chronic organ failure such as kidney and liver

• disorders that occur only in childhood, e.g. cystic fibrosis

• various genetic and congenital disorders, e.g. Huntington’s disease

Common characteristics

These disorders have some or all of the following characteristics in common:

• an increased likelihood of fear, psychological, social and spiritual distresses

• unpredictable symptoms, which are always changing and can be very distressing. There will be good days and bad days, which can add to the frustrations and stress of the patient, family and carers

• a lack of understanding of these disorders by some healthcare workers and by society in general, can unwittingly contribute to the person’s distress

• life-threatening, with shortened life expectancy – often quite significant, and the last phase of the illness probably being relatively short

• a ‘life’ pattern which can fluctuate quite markedly both in the individual and from person to person, e.g. there may be periods of remission, exacerbation or stability, or there may be a slow progressive decline; nevertheless, people may also appear fit and well with little or no change to their way of life

• the rate and manner of decline can fluctuate and varies considerably from person to person. The point comes when death is likely to occur in a matter of hours or days rather than weeks.

Symptoms

Below are some examples of distressing symptoms caused directly or indirectly by the disease or its treatment and commonly encountered in palliative care. Most, except possibly those marked with * can be helped or alleviated in some way by the essential oils listed alongside the individual symptoms in Appendix A II on the CD-ROM. More detailed information on the emotional aspects can be found in Aromatherapy and Your Emotions (Price 2000).

Physical examples

• Fatigue – no energy – always feeling tired/weak

• Poor appetite – loss of interest in food – nothing tastes or smells the same

• Feeling sick most/all of the time – smells, especially food/or sight/thought of food

• Vomiting* with or without nausea/with or without effort

• Sleep problems – can’t get to sleep/keep waking up

• Feeling out of breath all the time – and at rest/can’t breathe – panic attacks

• Mouth problems – dry – sore /ulcerated/infected – nasty taste

• Skin problems – dry/papery/marks or tears easily/lesions/bruising/rashes/sore/red

• Wound/stoma smells/‘I smell’

• Muscle spasms/rigidity/weakness/loss of control* – difficulty in swallowing*/dribbling of saliva*/attacks of choking*

• Loss of bladder control/constipation/diarrhoea

• reduced mobility – reduced dexterity

• Impaired sensation* – reduced/increased/altered – numbness/pins and needles

• Swollen limb(s)/swollen body

Psychosocial examples

• Shock and disbelief at the diagnosis, unable to make sense of what is happening – often described as ‘a whirlpool of emotions’

• Anger and frustration with delays in diagnosis, etc.

• Anxiety and fear of pain, the unknown, death itself, how, when and where they will die, fear of being alone when that time comes

• Tense, depressed, anxious, frightened and panicky – not able to say why

• Feeling helpless and no longer in control

• Worry about the future, how will their loved ones cope, how will it affect them

• Loss, grief, appearance, independence, different future

• Confusion, including disorientation (usually associated with brain tumours or dementia, can be due to medication)

• Withdrawing from people, not talking about their illness, keeping loved ones at a distance

• Low morale and self-esteem – ‘can’t be bothered’, ‘what’s the point’ etc.

Anxiety and panic

There is some evidence to show that aromatherapy massage can help relieve anxiety and aid relaxation (Hadfield 2001, Imanishi et al. 2007, Wilkinson et al. 2007). When patients are experiencing severe anxiety and panic there are many calming and sedative essential oils to choose from, such as Chamaemelum nobile [Roman chamomile], Canarium luzonicum (elemi) Cananga odorata [ylang ylang], Citrus aurantium var amara per. [orange bigarade] and

Case 15.1 Pain relief

Intervention

• Origanum majorana [sweet marjoram] – calming to the nervous system, analgesic for aching muscles

• Juniperus communis (fruct) [juniper berry] – helpful for painful joints and insomnia

• Chamaemelum nobile [Roman chamomile] – sedative, anti-inflammatory.

After 10 minutes she looked comfortable and relaxed, with no response when spoken to softly.

Citrus reticulata (mandarin] (also see Appendix B.9 on the CD-ROM). The patient can be asked to choose the aroma they find the most pleasing from a small selection of single oils, and/or a blend of two or three.

Spirituality

Being confronted with their own mortality often makes a person turn inwards and question their innermost thoughts, beliefs and values in an attempt to make sense of what is happening. The less a person is able to do physically, the more time they have for thinking, which can lead to much anguish and torment. Aromatherapy treatment may afford help in spiritual care, bringing comfort and peace in the form of deep relaxation. Patients may then be able to focus on their own spirituality. Essential oils that would help here are those which are both uplifting and soothing, analgesic and/or tonic to the heart, relieving any fears, e.g. Boswellia carteri [frankincense], Chamaemelum nobile [Roman chamomile], Citrus bergamia [bergamot], Lavandula angustifolia [lavender], Ocimum basilicum [sweet European basil] and Origanum majorana [sweet marjoram] (Price 2000; Tisserand 1992).

Pain – an example of the complex nature of a symptom

According to Twycross and Lack (1984) the perception of pain is modulated by the patient’s mood and morale, the meaning of pain to the patient and the

Case 15.2 Fungating lesion

Intervention

• Lavandula x intermedia [lavandin] – antiseptic, deodorant, calming, cicatrizant

• Citrus aurantium var. sinensis [sweet orange] – antiseptic, calming

• Myristica fragrans [nutmeg] – deodorant, analgesic, antibacterial

• Cupressus sempervirens [cypress] – deodorant, antiseptic, antibacterial

To help aid relaxation, shoulder massage was carried out in a 1% dilution in sweet almond oil with:

fact that pain may remain intractable if mental and social factors are ignored.

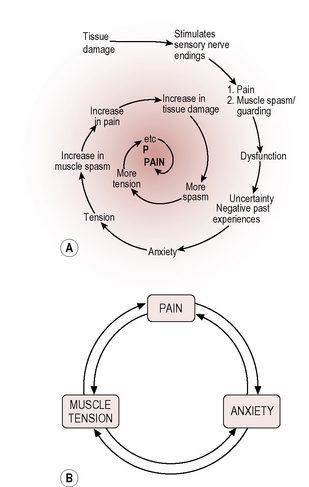

Pain is a warning of actual or potential tissue damage or pathology and creates some muscle tension (guarding) to protect the area. It elicits an arousal and an emotional response, and is modified by mental state and emotions (Marieb 1998). Most people with pain usually become anxious about the possible implications; this leads to more muscle tension, and muscle tension increases the pain that increases the emotional response, and so on, each perpetuating the other into a vicious circle that can become a spiralling process (McCaffery & Beebe 1989).

Localized pain and essential oils

Box 15.1 Some factors affecting pain threshold

| Threshold lowered by: | Threshold raised by: |

|---|---|

| Discomfort Insomnia Fatigue Anxiety Fear Anger Sadness Depression Boredom Introversion Mental isolation Social abandonment | Relief of symptoms Sleep Rest Sympathy Understanding Companionship Diversional activity Reduction of anxiety Elevation of mood Analgesics Anxiolytics Antidepressants |

In Chapter 8, Price discusses the effects that essential oils have on the emotions, which may or may not be a placebo response: according to Tisserand, if a smell is appealing, it soothes the mind (Tisserand 1992 p. 99). Placebo or not, if the experience of aromatherapy is pleasant and relaxing, even for a short time, it will surely have some beneficial effect on the patient’s mood and morale long enough to interrupt the vicious circle, thus helping them relax (Hadfield 2001), enhancing factors that raise a person’s tolerance level to their situation. This has a dual effect:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree