Overview of Safety and Risk Management

Drugs, like life, are not risk free.

–Anonymous

DEFINITIONS AND USES OF THE TERMS SAFETY AND RISKS

Safety is a frequently used word in the pharmaceutical industry, regulatory agencies, healthcare professional offices, the public’s mind, and the media. Yet the word safety only appears to mean “risk” to most people, and this definition is incomplete if not incorrect. Safety is more appropriately defined as the comparison (sometimes called the balance) of a drug’s risks and benefits.

Understanding risks alone are not sufficient to understand safety. One must factor in the concept of benefits as well. Consider this, an antihistamine that is associated with a high incidence of headaches of moderate severity would not be considered a “safe” drug because the benefits do not justify taking such a drug. However, an effective anticancer agent that caused the same incidence and severity of headaches (i.e., the risk) would definitely be considered a relatively safe drug. Even if the effective anticancer drug caused a higher incidence of severe headache and additionally caused nausea, vomiting, and hair loss, it would still be considered adequately safe because the clinical benefits would outweigh those adverse events.

Therefore, the risks which are much worse for the hypothetical anticancer drug, would be acceptable to most patients with cancer because the benefits would be agreed to be greater, and the drug’s overall safety profile would be deemed acceptable by regulators and practicing physicians. However, the risks of the less serious and less severe adverse events caused by the antihistamine means that its risks are unacceptable and its overall safety profile is negative.

THREE FRAMES OF REFERENCE TO VIEW SAFETY ISSUES

Lifecycle Approach to Viewing Drug Safety

The book The Future of Drug Safety by the Institute of Medicine (Baciu, Stratton, and Burke 2007) discusses a lifecycle approach to viewing drug risk and benefit. The essence of the main concept,

which is quite simple, is that a regulatory review should occur throughout a drug’s life after approval. While this concept is not new, it would be revolutionary if a formal system were to be developed and accepted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for implementation. The committee that authored this book makes several recommendations to Congress to give the FDA additional power and authority for enforcement to ensure compliance with postmarketing suggestions that go far beyond current practice and regulations. Some of the major recommendations are as follows:

which is quite simple, is that a regulatory review should occur throughout a drug’s life after approval. While this concept is not new, it would be revolutionary if a formal system were to be developed and accepted by the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) for implementation. The committee that authored this book makes several recommendations to Congress to give the FDA additional power and authority for enforcement to ensure compliance with postmarketing suggestions that go far beyond current practice and regulations. Some of the major recommendations are as follows:

Placing a symbol on all new products for two years to alert the public that the product is new. This period may be lengthened or shortened based on experience and the specific issues involved.

Establish performance goals for safety.

Hold industry and researchers accountable for making drug safety study results public for studies in Phase 2 through Phase 4.

Provide adequate resources and staff to do this work.

Have the FDA Commissioner appointed for a six-year term and limit the ability of the President to remove this person from office.

Increase communications from the FDA to the public with advice from a committee on communication with patients and consumers.

Review every new molecular entity approved within five years of its approval to ensure that the safety and efficacy are reassessed and found to be acceptable.

It should be noted that these recommendations are for mandatory standards and not voluntary ones.

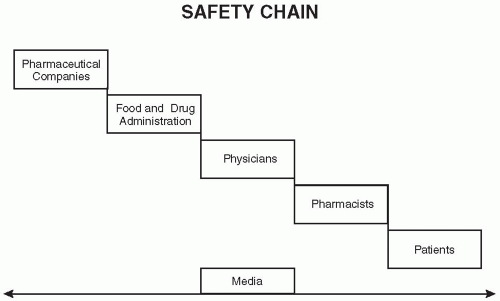

Three Umbrella Categories for Classifying Safety Issues

There are many issues that involve risks and benefits of drugs, so many in fact that it has become necessary to be able to create a frame of reference to be able to understand the scope of the many safety issues. This understanding should assist groups in being able to deal with these issues efficiently and effectively. The model (i.e., frame of reference) presented below places most safety issues into one of three broad categories, although some issues can easily fit into more than one of these three umbrella-type categories (i.e., inherent benefits and risks of a drug, FDA-related issues, and safe uses of drugs to minimize or eliminate medication errors). A separate frame of reference discussed later in this chapter reviews the “safety chain” which illustrates some of the interactions and relationships among various stakeholders in this area.

Inherent Benefits and Risks of Drugs

Those issues that involve the inherent benefits and risks of drugs focus on the medical benefits and the risks of adverse events, both expected and unexpected, and both known and unknown. These issues include those relating to the incidence of adverse events [i.e., how many occur per thousand (or per 10,000) patients], their degree of severity (i.e., are the adverse events mild, moderate or severe) and seriousness (e.g., do they cause a life-threatening event, cause hospitalization), and the relationship of those adverse events to the drug in terms of causality (is it unrelated, possibly related, probably related, definitely related, or of unknown relationship).

Some of the major safety issues over the past several years that fit this category include:

Hepatotoxicity as observed and reported in preclinical, clinical, and postmarketing studies

QTc prolongation of the cardiac electrical signal in the electrocardiogram and Torsades-de-Pointes

Increased use of active surveillance methodologies for seeking new signals and for evaluating actual or possible adverse events of marketed drugs

Risk management programs (discussed later in this chapter)

Reporting of adverse events by healthcare providers to the FDA, which are traditionally under-reported and contain insufficient information

Reproductive risks of taking drugs during pregnancy or safety during lactation

Safe Use of Drugs in Medical Practice and Clinical Trials

This category of issues involves the safe use of drugs that are available for use. This category involves the question of how drugs are being used in clinical practice by physicians, pharmacists, nurses, other healthcare professionals, and also by patients. This involves medication errors that arise as well as the larger overall category of medical errors of which medication errors are a small subset. There are many systems that are currently being implemented that seek to decrease the incidence of such errors, many of which will lead to lives saved. Some details are presented later in this chapter.

Regulatory Issues Relating to Safety of Drugs

This third broad category of issues includes those that primarily involve the FDA and other regulatory agencies. This category includes issues such as:

Are drugs being reviewed too rapidly by regulatory agencies?

Are the standards used to assess a drug’s safety appropriate or should they be changed?

What responsibilities do regulatory agencies have for monitoring safety in the postmarketing environment?

What systems for evaluating postmarketing safety should the regulators use or require companies to use?

Should a new office or institute to evaluate safety of new drugs be established that is independent of the national or other regulatory agency?

What postmarketing requirements and standards make sense for the nation given the current issues of safety being reported for newly approved drugs?

While all three of these areas are of critical importance, there has been a shift in the national focus on safety since 1998 when the first reports of an excess number of deaths from adverse events was reported in JAMA (Lazarou, Pomeranz, and Corey 1998). This article served to focus attention on the first broad category (i.e., inherent risks of drugs). A couple of years later, largely stimulated by two major reports from the Institute of Medicine of the National Academy of Sciences [To Err is Human (Kohn et al 2000) and Crossing the Quality Chasm (Institute of Medicine 2001)] the national focus changed fairly rapidly from looking at safety as an issue based on the inherent risks of drugs to looking at the medical use of drugs and the large number of medical errors that were occurring. The category of medical errors includes medication

(i.e., drug) errors. Immediately after publication of these books, there were widespread discussions on steps and methods that could be implemented to decrease both medical and medication errors, and these discussions and activities have continued through to the present and will hopefully continue into the future. It should be noted that medication errors were reported as a relatively minor subset (less than 10%) of the number of medical errors.

(i.e., drug) errors. Immediately after publication of these books, there were widespread discussions on steps and methods that could be implemented to decrease both medical and medication errors, and these discussions and activities have continued through to the present and will hopefully continue into the future. It should be noted that medication errors were reported as a relatively minor subset (less than 10%) of the number of medical errors.

Each group in the safety chain (see next section) was said to have responsibilities in policing its professionals, researching which methods and systems would decrease errors, and implementing such programs. Many programs have been implemented ranging from bar codes on packaging and drugs themselves to more computer generated orders for patients, and to systems that confirm requests received from physicians for their patients. These programs appear to be having a significant effect on decreasing medical and medication errors.

While there have always been questions about the FDA‘s roles and responsibilities in the safety area, and how well the agency has fulfilled its roles, recent reports have increased attention on the FDA. The national focus on safety is shifting from medical (and medication) errors to responsibilities of the FDA and how to improve the national system for evaluating safety and minimizing adverse events. It is anticipated that this will lead to a more detailed evaluation over the ensuing years of the FDA‘s systems, resources, standards, and oversight to implement methods for improving the safety of marketed drugs.

The Safety Chain

The safety chain is illustrated in Fig. 57.1.

The chain starts with the pharmaceutical company that develops and/or manufactures a drug and then has it approved for marketing by the FDA. After it is approved, physicians in hospitals and in outpatient settings are able to prescribe the drug for their patients. In outpatient settings, they provide a prescription to their patient or family member (or directly contact the pharmacy) where the prescription is filled and dispensed and given to the patient. After that point, the patient takes the drug. The in-hospital setting is clearly different in terms of how the prescription flows from physician through ordering channels to the pharmacy and then back to the nurses’ station and to the patient.

All along this process, there are innumerable places for problems or medical errors to occur. While the chain is presented as a sort of handoff, there are many feedback loops built into this system and many other groups and organizations that play a role in the processes described (e.g., Medicare, Medicaid, insurance companies, legislators, the public). There is one group, the media, which observes and comments on each step of the safety chain and also influences each of the groups in the safety chain. Therefore, in some ways the media is part of the safety chain as much as any of the parties shown in Fig. 57.1.

In addition to understanding the roles of each group, there are various issues or problems that may and do arise and, of course, there are many systems, procedures, and actions that can be implemented by each of the groups along this chain to improve their efficiency and also to both directly and indirectly decrease (or even prevent) medication errors from occurring.

MEDICAL AND MEDICATION ERRORS

The Institute of Medicine report on medical errors reported that about 98,000 people die from medical errors each year and that about 7,000 of those deaths are from medication errors.

While some medical errors may theoretically result from problems in pharmaceutical manufacturing process and relate to the quality of drugs, medication errors are rarely due to such pharmaceutical quality issues. Medication errors are more typically due to issues that arise at all stages of the safety chain and are not typically part of the drug development process. Packaging drugs in blister packs and using bar codes and other production mechanisms has reduced errors. Formulation approaches to reduce medication errors has focused on choice of

colors of tablets and solutions and other products, labeling of drugs with code numbers, and the many things that can be considered in drug packaging. For example, colors that are standardized for labeling different dose sizes of ampoules and vials could decrease errors in anesthetic drugs produced by different manufacturers (imagine a tired anesthesiologist reaching for a vial of 1:100,000 epinephrine and who misreads a label and picks up a vial with one zero more or less because all vials are simply packaged the same way versus having a broad red or green stripe across the label of all epinephrine vials of a specific concentration). Another area where errors can be reduced is by creating novel delivery systems that help to prevent misuse. Strong and tight standard operating procedures are already built into the pharmaceutical industry, pharmacies, and hospitals (see Chapter 58) and need to be tightened in other environments to decrease the number of medical and medication errors. Since the topic of medical errors (as opposed to medication errors) extends far beyond the scope of drug development, this important topic is not discussed.

colors of tablets and solutions and other products, labeling of drugs with code numbers, and the many things that can be considered in drug packaging. For example, colors that are standardized for labeling different dose sizes of ampoules and vials could decrease errors in anesthetic drugs produced by different manufacturers (imagine a tired anesthesiologist reaching for a vial of 1:100,000 epinephrine and who misreads a label and picks up a vial with one zero more or less because all vials are simply packaged the same way versus having a broad red or green stripe across the label of all epinephrine vials of a specific concentration). Another area where errors can be reduced is by creating novel delivery systems that help to prevent misuse. Strong and tight standard operating procedures are already built into the pharmaceutical industry, pharmacies, and hospitals (see Chapter 58) and need to be tightened in other environments to decrease the number of medical and medication errors. Since the topic of medical errors (as opposed to medication errors) extends far beyond the scope of drug development, this important topic is not discussed.

Reducing Medication Errors

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree