and Natalia Buza1

(1)

Department of Pathology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA

Keywords

Ovarian sex cord-stromal tumorsFibromaAdult granulosa cell tumorJuvenile granulosa cell tumorSertoli-Leydig cell tumorLeydig cell tumorSteroid cell tumor, NOSSclerosing stromal tumorIntroduction

Sex cord-stromal tumors represent the third group of ovarian tumors in decreasing order of frequency, with approximately 5–10 % of cases falling within this category. The most common entity among these tumors—ovarian fibroma—is readily recognized on frozen sections by a general surgical pathologist; however, other sex cord-stromal tumors may present a significant challenge due to their diverse morphology. In addition, unlike in other tumor types, the biological behavior of sex cord-stromal tumors is usually not directly linked to their microscopic degree of pleomorphism or cytological atypia. As an example, most adult granulosa cell tumors have uniform nuclei and relatively low mitotic activity, despite their locally aggressive behavior and overall 20–30 % recurrence rate. Similarly, the nuclear atypia may not be obvious in juvenile granulosa cell tumors and in biologically aggressive forms of Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors. While histological subtyping of primary ovarian epithelial malignancies on frozen section is typically not necessary and may be deferred for permanent sections, mere identification of an ovarian tumor as sex cord-stromal in origin, without recognition of the specific entity, is not sufficient for predicting outcome and guiding intraoperative management.

Endocrine/hormonal manifestations—estrogenic or androgenic—are relatively frequent in these tumors compared with other groups of ovarian neoplasms and may be helpful in the differential diagnosis at the time of frozen section.

Fibroma

Clinical features

Most common pure ovarian stromal tumor.

Most often occurs in middle-aged patients (mean 48 years).

May be associated with ascites, or rarely both ascites and pleural effusion—Meigs syndrome—in approximately 1 % of cases [1, 2].

Ascites is more common in tumors >10 cm.

May occur in patients with Gorlin syndrome (nevoid basal cell carcinoma syndrome) [3].

May present with acute abdominal pain due to torsion [4].

Gross pathology (Fig. 10.1)

Fig. 10.1

Fibroma. The ovarian surface is smooth and glistening (a). The cut surface is solid, firm, tan white (b) and may also be hemorrhagic due to torsion (c)

Mean tumor size is 6.8 cm [5].

Up to 8 % of cases are bilateral, mostly those that are associated with Gorlin syndrome.

Smooth ovarian surface.

Cut surface is solid, firm, white, or tan.

Hemorrhage and necrosis may be present, due to torsion.

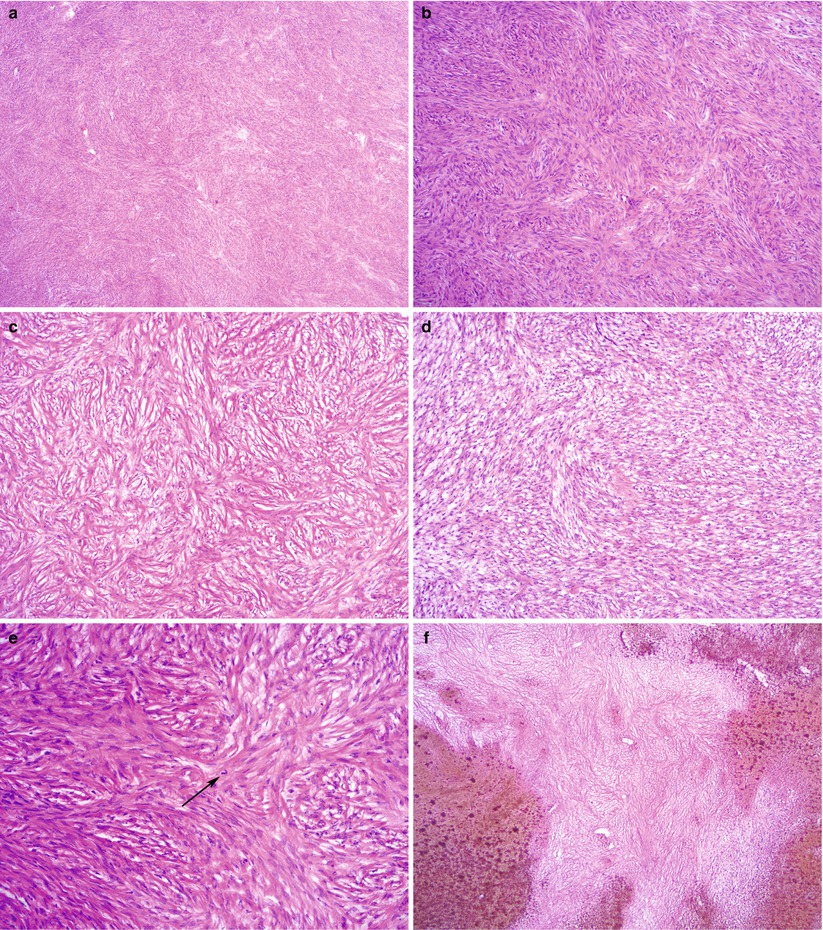

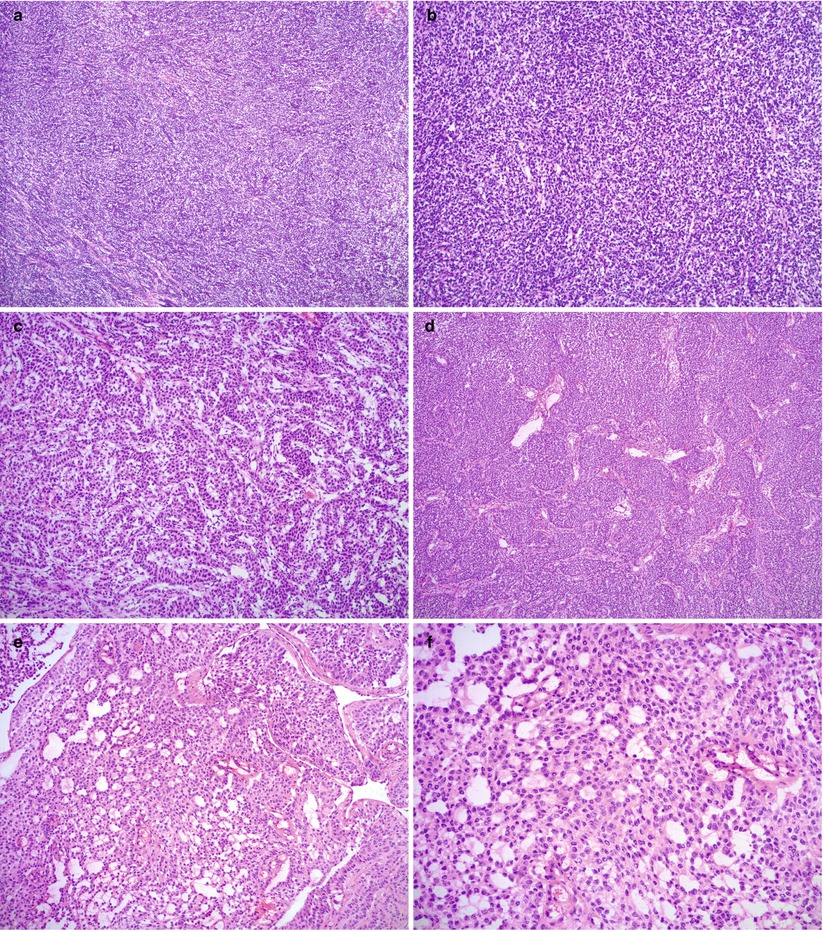

Microscopic features (Fig. 10.2)

Fig. 10.2

Fibroma. Note the variable cellularity and stromal hyalinization (a, b). The spindled tumor cells are arranged in a storiform pattern (c) or form intersecting fascicles (d). Mitotic figures may be seen (e, arrow). Hemorrhagic infarction of fibroma due to torsion (f) is not uncommon

Intersecting bundles/fascicles of spindle cells.

Storiform pattern, hyalinization, collagen bands, or plaques are often present.

Cellularity is variable.

Edema, hemorrhage, and hemorrhagic infarction may be seen due to torsion.

Nuclear atypia is absent or mild.

Low mitotic activity (≤3/10 high power field (HPF)).

Cellular tumors with mitotic activity of ≥4/10 HPF and no more than mild atypia have been termed mitotically active cellular fibroma [7].

No atypical mitotic figures.

Minor sex cord elements—granulosa cells or sertoliform tubules—may be present (<10 % of tumor on any slide) [8].

Differential diagnosis

Metastatic signet-ring cell tumors (Krukenberg tumor)

Adult granulosa cell tumor

Fibrosarcoma

Thecoma

Stromal hyperplasia/stromal hyperthecosis

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

The most clinically relevant differential diagnoses are adult granulosa cell tumor and metastatic carcinomas with reactive ovarian stromal proliferation.

Presence of minor sex cord elements (<10 % of tumor) has not been reported to have clinical significance in an otherwise typical fibroma.

Thorough sampling with additional blocks for frozen section is recommended to rule out an adult granulosa cell tumor or Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor.

Adult granulosa cell tumors may show a spindle-cell, “sarcomatoid” morphology, mimicking a fibroma/cellular fibroma.

Characteristic nuclear features of adult granulosa cell tumors—irregular nuclear membranes with nuclear grooves—may be difficult to appreciate due to frozen section artifact.

Identification of other morphologic patterns of adult granulosa cell tumor (i.e., insular, trabecular, or microfollicular) can be helpful—additional blocks may be sampled for frozen section.

Krukenberg tumor must be ruled out by careful microscopic examination.

Bilaterality should raise suspicion for metastasis, although up to 8 % of fibromas may be bilateral.

Scattered individual metastatic tumor cells with signet-ring or breast lobular carcinoma morphology may be missed on low magnification in a reactive/hyperplastic ovarian stroma.

Ovarian fibrosarcoma shows at least moderate nuclear atypia and increased mitotic activity (≥4/10 HPF), often with atypical mitotic figures.

Distinction between fibroma and other benign entities—thecoma, stromal hyperplasia/stromal hyperthecosis is not crucial at the time of frozen section.

Thecoma

Clinical features

Uncommon ovarian tumor.

Typically occurs in postmenopausal women.

May show symptoms associated with hormone production (most often estrogenic).

Luteinized thecomas tend to occur in younger (premenopausal) patients and may produce androgens [9].

Gross pathology

Most often unilateral.

Average size is 5–10 cm.

Cut surface is solid, yellow, but may contain white areas.

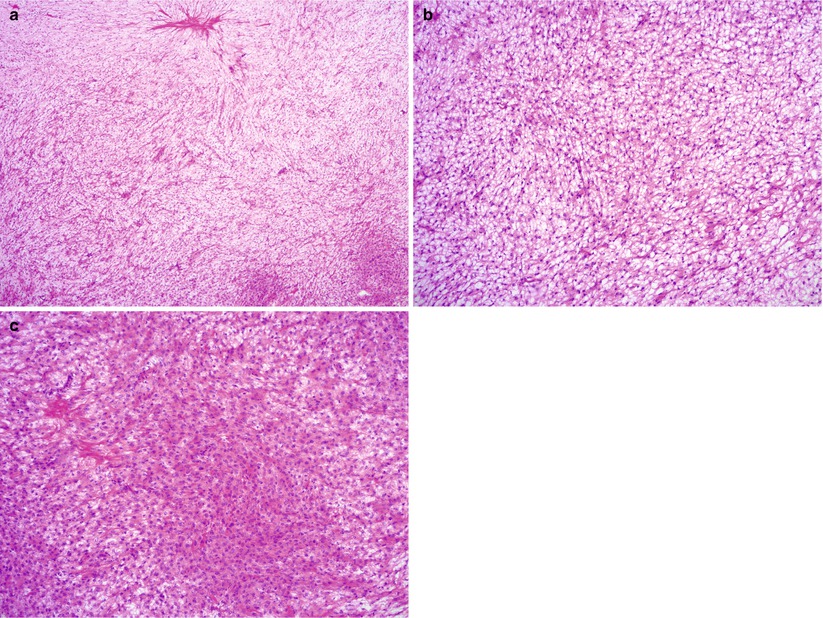

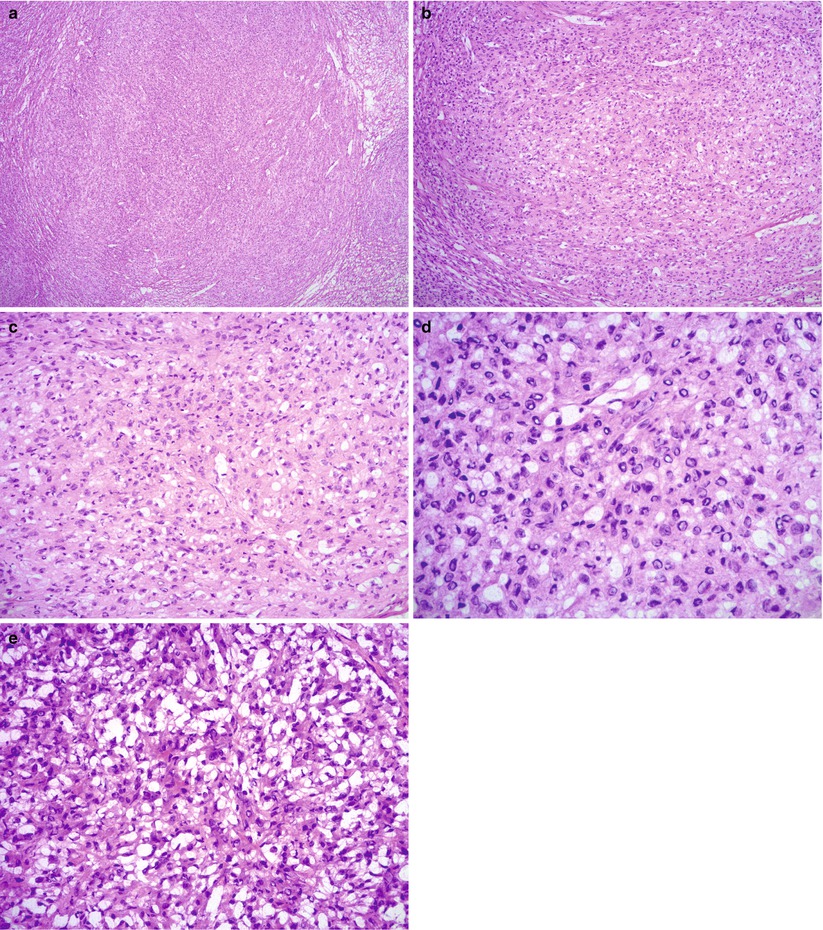

Microscopic features (Fig. 10.3)

Fig. 10.3

Thecoma. Note the sheets of round to oval, uniform cells with abundant eosinophilic or clear cytoplasm (a–c). Hyaline plaques may be seen (a, c)

Sheets composed of oval or round cells.

Moderate to abundant amount of pale eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Atypia is absent or minimal.

Mitoses are rare.

Hyalin plaques and focal calcifications may be seen.

May contain clusters of luteinized cells with pink or clear cytoplasm.

Areas resembling a fibroma are not uncommon; these tumors can be designated as fibrothecoma.

Differential diagnosis

Adult granulosa cell tumor

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor

Fibroma

Steroid cell tumor

Leydig cell tumor

Stromal-Leydig cell tumor

Stromal hyperplasia/stromal hyperthecosis

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

The most clinically relevant differential diagnosis is adult granulosa cell tumor, which typically requires complete surgical staging.

Adult granulosa cell tumors may show luteinization, closely resembling thecomas/luteinized thecomas, and on frozen sections—without the help of ancillary studies—the distinction between the two entities may be very difficult.

In such cases, the frozen section slide could be interpreted as “sex cord-stromal tumor with luteinization,” and the diagnosis could be deferred for permanent sections to avoid overdiagnosis.

Luteinized cells in thecomas may raise the possibility of a Leydig cell or Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor. While distinction between a Leydig cell tumor and a luteinized thecoma is not critical at the time of frozen section, identification of a Sertoli cell component is important, as a surgical staging procedure is typically performed for Sertoli-Leydig cell tumors [10]

Presence of intracytoplasmic Reinke crystals—which may be better preserved on frozen sections than on permanent sections after formalin fixation—confirms Leydig cells

Distinction between fibroma and other benign entities—thecoma, stromal hyperplasia/stromal hyperthecosis is not crucial at the time of frozen section.

Tumors with fibromatous areas and foci of luteinization or features of thecoma may be designated as fibrothecoma.

Luteinized Thecoma with Sclerosing Peritonitis

Rare, distinctive clinicopathologic entity

Typically occurs in young women (median 27 years) and presents with abdominal distension due to ascites and occasionally bowel adhesions [11].

Most often bilateral with tan to red-brown cut surface.

Hypercellular with spindled tumor cells and rare round, luteinized cells.

Edema, microcyst formation, and increased mitotic activity are not uncommon.

Adult Granulosa Cell Tumor (AGCT)

Clinical features

May occur at any age, but most often in postmenopausal patients—the peak incidence is between 50 and 55 years of age [12–14].

May present with pelvic mass/pain.

Endocrine—most often estrogenic—manifestations are common and include abnormal bleeding: postmenopausal bleeding, menorrhagia, metrorrhagia, or amenorrhea.

Concurrent endometrial hyperplasia or well-differentiated endometrioid endometrial adenocarcinoma may be seen in approximately 25 % and 5 % of cases, respectively [15].

Approximately 10 % of patients present with acute abdomen, due to tumor rupture, hemoperitoneum, or torsion [13].

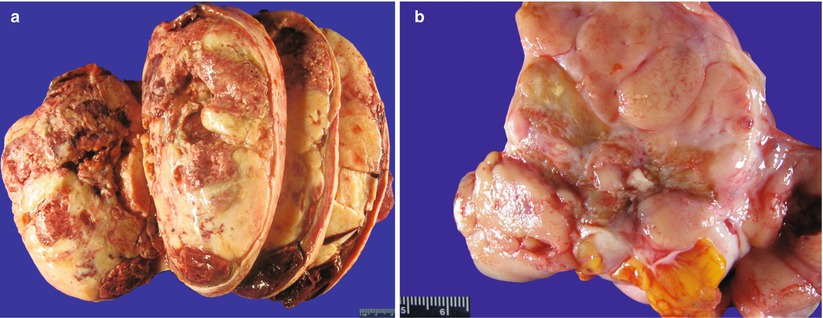

Gross pathology (Fig. 10.4)

Fig. 10.4

Adult granulosa cell tumor (AGCT). The cut surface of the tumor is solid, tan-yellow (a) or tan-pink (b). Hemorrhage and cystic changes are commonly present (a)

Most often unilateral (>95 % of cases).

Size may vary from microscopic up to 40 cm; average 10–12 cm [12].

Cut surface is typically solid and cystic, tan-yellow, or white.

Less often it may be entirely solid or entirely cystic (uni- or multilocular).

Foci of hemorrhage are common.

Consistency may be firm or soft, friable, depending on the amount of fibrous stroma.

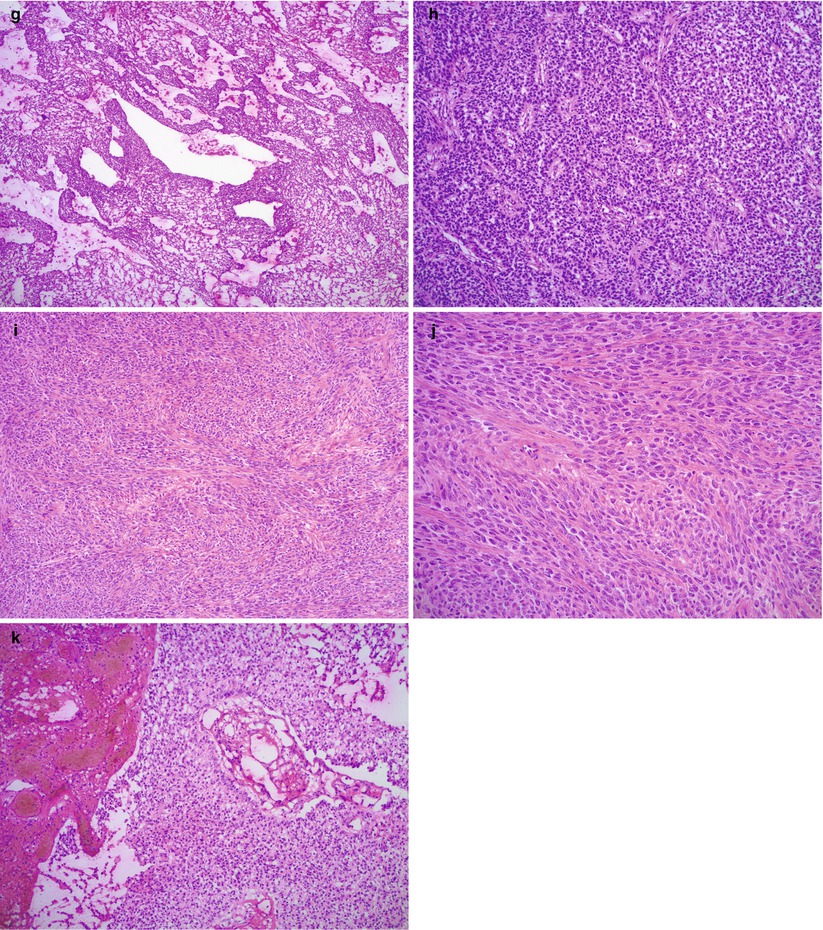

Microscopic features (Figs. 10.5, 10.6, and 10.7)

Fig. 10.5

Histological features of adult granulosa cell tumor (AGCT). Note the various morphologic patterns: diffuse (a, b), trabecular (c), insular (d), microfollicular (e, f), macrofollicular (g), pseudopapillary (h), and sarcomatoid (i, j). Hemorrhage is not uncommon (k)

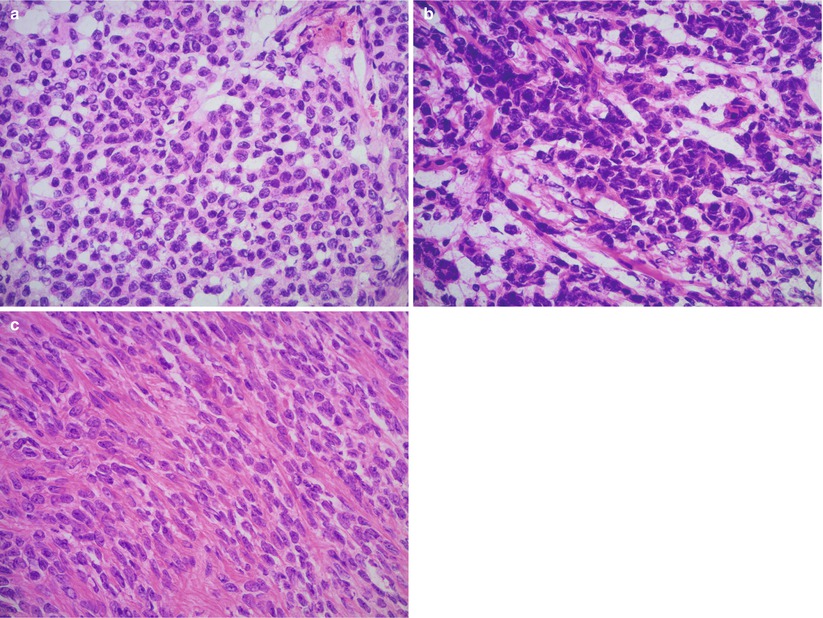

Fig. 10.6

Cytological features of adult granulosa cell tumor (AGCT). The tumor cells have round to oval nuclei with irregular nuclear membranes and longitudinal grooves, pale chromatin, small nucleoli, and scant eosinophilic cytoplasm (a–c). Note the vague trabecular arrangement of tumor cells (b) in a tumor with a predominant diffuse growth pattern

Fig. 10.7

Luteinized adult granulosa cell tumor (AGCT). Note the diffuse growth pattern (a, b) and characteristic abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and round nuclei lacking grooves (c, d). Frozen section artifact may result in cytoplasmic clearing, mimicking signet-ring cells (e)

Various morphologic patterns, often admixed within the same tumor.

Common patterns

Diffuse: most common pattern with nonspecific arrangement of tumor cells in large sheets

Insular: well-defined nests of tumor cells surrounded by fibromatous stroma

Trabecular: trabecular or cordlike arrangement

Less common/uncommon patterns

Microfollicular: tumor cells surrounding small round spaces filled with eosinophilic material (Call-Exner bodies)—only seen in minority of granulosa cell tumors

Macrofollicular: larger cystic spaces lined by tumor cells

“Watered silk” and gyriform patterns: undulating files or rows of tumor cells

Pseudopapillary: central vascular core lined by tumor cells—may be a degenerative phenomenon

Sarcomatoid: spindled cells, resembling cellular fibroma

Tumor cells are relatively uniform with scant pale cytoplasm and round to oval nuclei.

The chromatin pattern is pale and the nuclear membrane is characteristically irregular with folds resulting in nuclear grooves.

Nuclear grooves may be difficult to appreciate on frozen sections due to freezing artifact.

Luteinized AGCTs have a more abundant pink cytoplasm and most often lack nuclear grooves.

Mitotic activity is variable, but usually <3/10 HPF in most tumors.

Atypical mitotic figures are usually absent.

Rare tumors may show marked cytological atypia with bizarre nuclei [18].

Hemorrhage and necrosis may be seen, the latter usually secondary to torsion.

Differential diagnosis (Table 10.1)

Table 10.1

Differential diagnosis of adult granulosa cell tumor (AGCT)

AGCT

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma

Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor

Carcinoid tumor (primary)

Dysgerminoma

Age (years)

Most often postmenopausal (mean 50–55)

5th–6th decades (mean 58)

Most common in young patients (mean: 25–30)

14–79 years (mean 53)

2nd–3rd decades (mean: 22)

Bilaterality

Very rare

Up to 17 %

Very rare

Very rare (suspect metastasis if bilateral)

10–20 %

Size (mean)

10–12 cm

15 cm

12–14 cm

Variable

Most often >10 cm

Clinical symptoms

Pelvic mass/pain; hormonal (estrogenic > androgenic) manifestations

Asymptomatic or pelvic mass/pain

Hormonal manifestations common (androgenic > estrogenic)

May be incidental; one-third of patients have carcinoid syndrome

Pelvic mass/pain; increased serum LDH

Cytoplasmic features

Little cytoplasm, cell membrane not well defined, except luteinized AGCT

Moderate to abundant; may show squamous and mucinous differentiation

Leydig cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm containing lipofuscin pigment and Reinke crystals

Moderate amount, may show mucinous differentiation (goblet cell carcinoid)

Abundant clear or pale eosinophilic cytoplasm; well-defined cell borders

Nuclear features

Most often uniform, pale nuclei with membrane folds and grooves

Variable nuclear atypia; no grooves

Grade dependent; nuclear membrane folds and grooves may be seen in Sertoli cells

Uniform, small, round nuclei with finely stippled chromatin

Uniform nuclear enlargement with prominent nucleoli

Necrosis

May be seen

Common

May be seen (in poorly differentiated tumors)

Absent

Common

Primary ovarian carcinomas—endometrioid adenocarcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, and small cell carcinoma

Metastatic carcinomas—breast, pancreatic, and small cell carcinoma

Carcinoid tumor—primary or metastatic

Sex cord-stromal tumors—Sertoli-Leydig cell tumor, juvenile granulosa cell tumor, thecoma, and fibroma

Germ cell tumors—dysgerminoma

Lymphoma

Follicle cyst versus unilocular AGCT

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

In postmenopausal patients with AGCT, the surgical treatment includes total hysterectomy, bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy as part of the complete surgical staging [19].

Fertility-sparing surgery may be performed in younger patients with tumors confined to one ovary (without surface involvement) and includes unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, staging procedure (with or without lymphadenectomy), and intraoperative assessment of the contralateral ovary [19, 20].

Ovarian surface involvement should be reported if identified grossly or microscopically on frozen section, as it may preclude fertility-sparing surgery.

Clinically the most important distinction at the time of frozen section is between AGCT and its benign mimics among sex cord-stromal tumors and carcinomas metastatic to the ovary, as no surgical staging would be required for the latter two categories of lesions.

Bilaterality, marked nuclear atypia and high mitotic activity with abnormal mitotic figures are not typical features of AGCT and should raise suspicion for carcinoma—primary or metastatic.

Clinical history of prior malignancy and morphologic comparison with prior biopsies—if available—is very helpful.

Carcinomas typically have more abundant cytoplasm than AGCT.

Characteristic nuclear features of AGCT—uniform, oval nuclei with irregular, folded nuclear membranes and grooves—are distinct from those of carcinomas.

Distinction between primary ovarian carcinoma and AGCT is less critical on frozen section, as the surgical management is the same in most cases.

In young patients, fertility-sparing surgery may be performed for AGCT, but its role in epithelial malignancies is more controversial.

AGCT with microfollicular pattern can mimic carcinoid tumors—primary or metastatic.

Carcinoid tumors characteristically have round nuclei with smooth nuclear membranes, stippled chromatin pattern in contrast to the oval nuclei and grooves of AGCT.

AGCT with a diffuse morphologic pattern may mimic a fibroma or cellular fibroma.

Identification of other morphologic patterns of AGCT—insular, trabecular or microfollicular—is most helpful, and it may require careful microscopic examination or sampling of additional tissue blocks.

AGCT with luteinization can pose a significant diagnostic challenge on frozen section evaluation, closely mimicking a thecoma/fibrothecoma.

Luteinized AGCT usually has more abundant pink cytoplasm and lacks nuclear grooves.

Distinct tumor nodules are more in favor of AGCT, while a diffuse pattern is more common in thecomas.

In difficult cases, the frozen section slide could be interpreted as “sex cord-stromal tumor with luteinization,” and the diagnosis could be deferred for permanent sections.

Distinction between adult and juvenile granulosa cell tumors on frozen section is typically not critical for intraoperative management.

Frozen section artifacts often hamper the morphologic interpretation:

Artifactual cytoplasmic clearing may raise the possibility of clear cell carcinoma or dysgerminoma.

Artifactual clearing of nuclei may obscure the characteristic nuclear features.

Evaluation of endometrium: If the diagnosis of AGCT is made on frozen section, evaluation of the endometrium is also recommended—at least grossly or both grossly and microscopically—if a hysterectomy specimen is available

If the uterus will be spared, an endometrial curettage during the same procedure is recommended to rule out endometrial hyperplasia or carcinoma.

Juvenile Granulosa Cell Tumor (JGCT)

Clinical features

Much less common than AGCT, representing approximately 5 % of granulosa cell tumors.

Usually occurs within the first three decades, although rarely may also occur in older women [21].

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree