and Natalia Buza1

(1)

Department of Pathology, Yale University School of Medicine, New Haven, CT, USA

Keywords

Serous ovarian tumorsPeritoneal and lymph node involvement by serous tumorsMucinous ovarian tumorsEndometrioid ovarian tumorsClear cell ovarian tumorsBrenner tumorsMixed epithelial-mesenchymal tumors of ovaryIntroduction

Surface epithelial tumors are the most common group of ovarian neoplasms in general and represent approximately 90 % of ovarian malignancy; hence, they are one of the most frequently encountered gynecologic specimens in the frozen section laboratory. Preoperative diagnostic workup of ovarian tumors is usually limited to imaging studies and serum markers, both of which suffer from low sensitivity and specificity. Intraoperative frozen section evaluation therefore is crucial for determining the required extent of surgery: limited cystectomy or unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy for benign tumors—especially in young patients desiring fertility preservation—or extensive staging procedure with bilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, lymph node dissection, omentectomy, and peritoneal biopsies for ovarian carcinomas. Accurate diagnosis and classification of borderline (atypical proliferative) tumors may also allow for conservative surgical management and fertility preservation in the reproductive age group [1, 2]. Misinterpretation of the frozen section, on the other hand, may result in unnecessary extensive surgical procedure or will put the patient at risk for a second surgery.

Combination of careful gross examination, appropriate sampling, and interpretation of morphologic findings along with familiarity of the clinical context is key to the accurate frozen section diagnosis and successful intraoperative consultation on epithelial ovarian tumors. The proportion of solid and cystic areas on gross examination may provide a preliminary impression in this group of neoplasms, as vast majority of completely cystic tumors with a smooth lining and without solid nodules is histologically benign [3]. On the other hand, many of the benign epithelial tumors have a partially or entirely solid cut surface, e.g., adenofibromas or benign Brenner tumors. Serous tumors, both benign and malignant, are often bilateral; however, bilaterality of mucinous tumors—especially those with borderline or overt malignant features—should always raise suspicion for metastasis. In addition, mucinous tumors generally require more extensive sampling even at the time of frozen section, due to their significant histological heterogeneity. Clinical history of any previous malignancy is very important in this setting, but may not be provided by the clinical team unless asked specifically. The patient’s age and reproductive status also play a significant role in the frozen section consultation of ovarian epithelial tumors. The distinction between borderline tumors and invasive carcinomas may be difficult at the time of frozen section and a conservative approach may be appropriate, especially in young patients to avoid overdiagnosis of carcinoma.

The differential diagnosis of epithelial ovarian tumors also includes other primary ovarian neoplasms—e.g., sex cord-stromal tumors, germ cell tumors, and other miscellaneous neoplastic or nonneoplastic conditions, which will be separately discussed in detail within the following chapters.

Serous Ovarian Tumors

Serous Cystadenoma

Clinical features

Usually adults; mean age between 40 and 60 years

Up to 20 % bilateral

Gross pathology (Fig. 8.1)

Fig. 8.1

Serous cystadenoma macroscopic appearance: smooth ovarian surface (a) and unilocular cyst with thin wall and a smooth cyst lining without papillary excrescences (b)

Uni- or oligolocular cyst.

Up to 30 cm in size, mean: 5–8 cm.

Smooth external surface.

Typically filled with clear, watery fluid; occasionally appears thicker, mucoid in consistency.

Smooth inner lining without solid areas or papillary excrescences.

Gross sampling should include multiple fragments or “rolled up” cyst wall in one block.

Microscopic features (Fig. 8.2)

Fig. 8.2

Serous cystadenoma. The cyst is lined by ciliated tubal-type epithelium (a, b) often with nuclear pseudostratification (c). Significant epithelial proliferation, tufting, and cytological atypia are absent

Single layer of cuboidal to columnar cells, resembling tubal-type epithelium; often with pseudostratification of nuclei.

Ciliated cells are present.

No cytological atypia.

No significant epithelial proliferation.

Differential diagnosis

Serous cystadenoma with focal epithelial proliferation (<10 % of epithelial lining shows atypical proliferation) [4, 5]

Serous borderline tumor (SBT)/atypical proliferative serous tumor (APST)

Mucinous cystadenoma; especially when cyst contents appear grossly mucinous

Endometriosis

Other cystic benign, nonneoplastic lesions (e.g., paratubal cyst, hydrosalpinx, cystic follicle/follicular cyst)

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

Tangential sectioning of serous/tubal-type epithelium may mimic epithelial proliferation.

Prominent pseudostratification of nuclei may mimic epithelial proliferation/atypia.

Serous cystadenoma with focal epithelial proliferation (<10 % of epithelial lining shows atypical proliferation) [4, 5].

Does not meet criteria for SBT/APST, no staging surgery is necessary.

Additional frozen section sampling should be pursued to rule out SBT/APST.

Surgeon may be advised that additional sampling for permanent sections could increase the percentage of atypical proliferation, especially in large tumors.

SBT/APST

Epithelial proliferation and tufting in at least 10 % of tumor with mild cytological atypia

Mucinous cystadenoma

Classification/diagnosis is based on histological cell type, not gross appearance of cyst contents.

Surgeon may perform appendectomy if the frozen section diagnosis indicates a mucinous cystadenoma (see mucinous ovarian tumors).

Precise distinction from benign, nonneoplastic cystic lesions is typically not required on frozen section.

Serous Cystadenofibroma/Adenofibroma

Clinical features

Usually occurs in adults, with a mean age between 40 and 60 years

Up to 20 % bilateral

Gross pathology (Fig. 8.3)

Fig. 8.3

Serous cystadenofibroma. The ovarian surface is often lobulated and may show coarse papillary projections (a). The cyst lining may also show coarse, firm papillary protrusions into the lumen (b)

Surface may be lobulated or have coarse, firm papillary projections.

Variable proportion of cystic and solid areas.

Lining of cystic component may have papillary projections, which are typically firm and coarse

Serous adenofibromas without a cystic component have a solid, firm cut surface occasionally with visible small lumina (“spongelike” appearance).

Gross sampling should be focused on papillary and solid areas, with multiple blocks if necessary.

Microscopic features (Fig. 8.4a, b)

Fig. 8.4

Serous cystadenofibroma. Note the broad, fibrous papillae lined by a single layer of serous (tubal-type) epithelium (a, b). Tangential sectioning may result in pseudostratification mimicking epithelial proliferation (c)

Broad, fibrous papillae lined by a single layer of serous (tubal-type) epithelium, protruding into the cyst lumen (cystadenofibroma) or scattered glands with serous (tubal-type) lining embedded in fibrous stroma (adenofibroma).

Ciliated cells are present.

No cytological atypia or significant epithelial proliferation.

May show focal calcifications (stromal or epithelial).

Differential diagnosis

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

Tangential sectioning of serous/tubal-type epithelium may mimic epithelial proliferation (Fig. 8.4c).

Prominent pseudostratification of nuclei may mimic epithelial proliferation/atypia (see Fig. 8.2c).

Serous cystadenofibroma with focal epithelial proliferation (<10 % of epithelial lining shows atypical proliferation) [4, 5] (Fig. 8.5).

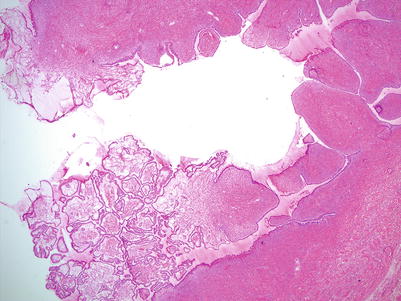

Fig. 8.5

Serous cystadenofibroma with focal epithelial proliferation. Focal papillary epithelial proliferation is seen on low magnification in the left lower portion of this serous cystadenofibroma, comprising less than 10 % of the entire epithelial lining

Does not meet criteria for SBT/APST, has been shown to have a benign clinical course, and does not require staging surgery.

Additional frozen section sampling should be pursued to rule out SBT/APST.

Surgeon may be advised that additional sampling for permanent sections could increase the percentage of atypical proliferation, especially in large tumors.

SBT/APST

Papillary projections of the cyst lining in serous cystadenofibroma are typically firm and coarse, scattered, and few in number—in contrast to the large number of soft, friable papillary intraluminal growth in SBT/APST.

Serous Borderline Tumor (SBT)/Atypical Proliferative Serous Tumor (APST)

Gross pathology

Typically cystic.

Can have a wide size range, although usually >5 cm [6].

Abundant friable papillary projections on the cyst lining (Fig. 8.6a).

Fig. 8.6

Serous borderline tumor (SBT)/atypical proliferative serous tumor (APST). The cut surface shows a unilocular cyst with abundant, friable tan-pink intraluminal papillary projections (a). Occasionally SBT/APST presents as a solid surface growth with a “cauliflower-like” gross appearance (b)

Papillary projections may also be present on the ovarian surface.

Less commonly the entire tumor presents as a “cauliflower-like” surface mass without a cystic component (Fig. 8.6b).

Inking of ovarian surface (at least in the area where frozen sections are submitted from) is helpful in determining surface involvement.

Gross sampling should be focused on intracystic and surface papillary and solid areas, with multiple blocks if necessary.

Microscopic features

Hierarchical branching papillae (Fig. 8.7a).

Fig. 8.7

Microscopic features of SBT/APST. Note the hierarchical branching papillae (a, b) and epithelial proliferation with tufting (b, c). The tumor cell nuclei are mildly atypical with occasional conspicuous nucleoli (d). Psammoma bodies are often present (d , right upper corner). Hobnail cells and round, eosinophilic cells are also common (e)

Epithelial proliferation in the form of stratification (multiple cell layers, rather than multiple layers of nuclei as seen in “pseudostratification” of benign tumors), budding, and tufting in at least 10 % of tumor (Fig. 8.7b, c).

Micropapillary or cribriform architectural pattern may be seen focally (<5 mm) [6].

Mild to moderate nuclear atypia with oval to round nuclei (Fig. 8.7d).

Nucleoli are usually inconspicuous, but occasionally may be prominent.

Low mitotic activity.

Ciliated, hobnail, and round eosinophilic cells are often present (Fig. 8.7e).

Psammomatous calcifications within the epithelium or stroma (see Fig. 8.7d)

Psammomatous calcifications are nonspecific; may also be seen in benign serous tumors, as well as low-grade and high-grade carcinomas

Microinvasion (<5 mm in greatest dimension) may be present: round eosinophilic cells (single cells or small clusters) in a desmoplastic stroma (Fig. 8.8).

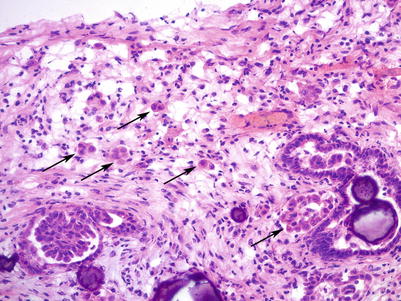

Fig. 8.8

Microinvasion in SBT/APST. Note the small clusters of round, eosinophilic tumor cells in a desmoplastic stroma (arrows). Numerous psammoma bodies are also seen

Differential diagnosis

Serous cystadenoma/cystadenofibroma

Serous cystadenoma with focal epithelial proliferation (<10 % of epithelial lining shows atypical proliferation) [4, 5]

Mucinous/seromucinous borderline tumor

SBT/APST micropapillary variant/noninvasive low-grade serous carcinoma

Low-grade serous carcinoma

High-grade serous carcinoma

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

Serous cystadenoma/cystadenofibroma may mimic a SBT/APST due to pseudostratification (multiple layers of nuclei, as opposed to multiple layers of cells in true epithelial stratification of SBT/APST) or tangential sectioning of the epithelium. Cystadenoma/cystadenofibroma lacks cytological atypia and has oval or elongated nuclei, rather than the more commonly round nuclei of SBT/APST.

Serous cystadenoma/adenofibroma with focal atypical epithelial proliferation: It may be difficult to estimate the percentage of epithelial proliferation within a cystic serous tumor based on limited number of frozen sections. If based on both gross and microscopic examination—the epithelial proliferation is relatively focal and there is a chance that it may fall under 10 % after thorough sampling on permanent sections, a conservative frozen section interpretation of “serous cystadenoma with focal epithelial proliferation” may be reported, especially in young patients. The surgeon should be advised that additional sampling might increase the percentage of involvement and result in an upgrade to SBT/APST on the final diagnosis.

Definitive diagnosis of microinvasion or microinvasive carcinoma in SBT/APST on the frozen sections is typically not necessary for clinical management; frozen section diagnosis of “serous borderline tumor” or “at least serous borderline tumor” is appropriate. Presence of microinvasion does not have a significant impact on survival [5, 8].

SBTs/APSTs may display more nuclear irregularity, pleomorphism, and prominent nucleoli, raising the differential of low-grade serous carcinoma. Stromal invasion measuring >5 mm should be classified as invasive low-grade serous carcinoma.

The distinction between SBT/APST and noninvasive (SBT/APST micropapillary variant) or invasive low-grade serous carcinoma is typically not crucial at the time of frozen section; frozen section diagnosis of “at least serous borderline tumor” or “serous borderline tumor with micropapillary features” is appropriate.

High-grade serous carcinomas (HGSC) may have a predominantly papillary architecture mimicking SBT/APST on low magnification. However on higher magnification HGSC shows marked nuclear pleomorphism, numerous mitotic figures and often necrosis, none of which are features of SBT/APST. Identification of the more common solid or glandular patterns (with “slit-like” configurations) is also helpful in making the diagnosis of HGSC, and ruling out SBT/APST. HGSC requires complete surgical staging, in contrast to the optional conservative—fertility-preserving—surgery for SBT/APST, which typically affects a younger patient group.

SBT/APST Micropapillary Variant/Noninvasive Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma

Clinical and gross features

Similar to SBT/APST

May be more often bilateral [9]

Microscopic features

Non-hierarchical branching micropapillary or cribriform architecture—in at least one confluent area measuring 5 mm [6] (Fig. 8.9).

Fig. 8.9

SBT/APST—micropapillary variant/noninvasive low-grade serous carcinoma. Note the non-hierarchical branching of long, slender micropapillae (at least 5 times longer than wide) (a, b) or cribriform architecture (c)

Micropapillae are at least five times taller than wide with scant or no fibrovascular cores.

Micropapillae are smoothly contoured.

Round or polygonal, uniform nuclei; slightly more nuclear atypia and higher nuclear to cytoplasmic (N/C) ratio than SBT/APST.

Ciliated cells are absent.

Low mitotic activity (but may be slightly higher than SBT/APST).

Differential diagnosis

SBT/APST with extensive tufting and eosinophilic metaplasia

SBT/APST with focal micropapillary features (<5 mm)

Low-grade serous carcinoma, invasive

High-grade serous carcinoma

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

Prognostic significance of micropapillary variant of SBT (noninvasive low-grade serous carcinoma) is controversial, has been reported to be clinically more aggressive than SBT/APST in some studies [6, 10, 11].

The distinction between SBT/APST and SBT micropapillary variant (noninvasive low-grade serous carcinoma) may not be crucial at the time of frozen section depending on the patient’s age and fertility status. Frozen section diagnosis of “serous borderline tumor,” “at least serous borderline tumor” or “serous borderline tumor with micropapillary features” may be communicated.

Fertility-sparing surgery may be performed in younger patients.

High-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) shows marked nuclear pleomorphism, numerous mitotic figures, and often necrosis, none of which are features of SBT/APST. One should be very cautious when considering HGSC in the reproductive age group, as it is a highly aggressive tumor, requiring complete surgical staging.

Low-Grade Serous Carcinoma (LGSC), Invasive

Clinical features

Gross pathology

Solid or partially cystic mass with papillary growth (Fig. 8.10).

Fig. 8.10

Low-grade serous carcinoma showing a predominantly solid, tan-pink cut surface

Cut surface may appear gritty, due to calcifications.

Necrosis is practically absent.

Inking of ovarian surface (at least in the area where frozen sections are submitted from) is helpful in determining surface involvement.

Gross sampling for frozen section should be focused on solid and papillary areas, with multiple blocks if necessary.

Microscopic features (Fig. 8.11)

Fig. 8.11

Low-grade serous carcinoma. The tumor cells infiltrate the stroma forming irregular nests or micropapillae with abundant psammoma bodies (a, b). Mild to moderate nuclear atypia with conspicuous nucleoli is seen (c)

Irregular small nests, micro- or macro-papillae, or single cells.

Destructive stromal invasion.

Relatively uniform nuclei with mild to moderate atypia.

Nuclear pleomorphism is usually slightly increased compared to SBT/APST.

Prominent nucleoli may be seen.

Low mitotic activity (<12 mitoses/10 high-power field).

Psammomatous calcifications may be abundant (“psammocarcinoma”).

Necrosis is practically absent.

Differential diagnosis

SBT/APST

SBT/APST—micropapillary variant/noninvasive low-grade serous carcinoma

High-grade serous carcinoma

Malignant mesothelioma (see Chap. 13)

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

The distinction between LGSC and SBT/APST may not be crucial at the time of frozen section. Requesting additional biopsies from any extraovarian lesions or implants—if detected by the surgeon—may be helpful in identifying destructive stromal invasion and establishing the diagnosis of LGSC.

Although high-grade serous carcinoma (HGSC) may show focal or predominant papillary architecture mimicking LGSC, presence of other types of growth patterns—solid and glandular with slit-like spaces—is a helpful diagnostic clue for HGSC. In addition, HGSC shows marked nuclear pleomorphism and numerous mitotic figures. Necrosis is also common in HGSC, while it is practically absent in LGSC.

Peritoneal Implants of SBT/APST (Noninvasive)

Microscopic features

Hierarchical branching papillae or detached cell clusters, histologically similar to ovarian SBT/APST (epithelial-type noninvasive implants) (Fig. 8.12).

Fig. 8.12

Peritoneal implants of SBT/APST (a, b). Noninvasive epithelial implants of SBT/APST show hierarchical branching of atypical papillary epithelial proliferation without stromal invasion. Psammomatous calcifications are often present

Desmoplastic noninvasive implants are associated with significant desmoplastic reaction without infiltrative growth.

Differential diagnosis

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

Endosalpingiosis consists of simple benign glands lined by a single layer of columnar, tubal-type epithelium. No epithelial proliferation, tufting, or atypia is seen. Calcifications may be present.

Low-grade serous carcinoma (LGSC) (previously termed “invasive implants”) shows destructive stromal invasion and generally increased nuclear atypia, compared to (noninvasive) implants of SBT/APST.

Distinction between LGSC and noninvasive implants of SBT/APST may not be crucial at the time of frozen section—especially in the older age group—the differential diagnosis may be communicated to the surgeon.

Sampling of additional peritoneal lesions or the ovary for frozen section may be helpful if more specific classification is desired.

Well-differentiated papillary mesothelioma [see also Chap. 13] is a benign entity usually presenting as a small (<2 cm), incidental solitary papillary lesion, without any nuclear atypia or mitotic activity. Clinical correlation with the surgeon regarding the intraoperative findings is important. Extensive or multifocal lesions should raise concern for malignant mesothelioma or other entities in the differential (e.g., serous tumors/implants). Surgical sampling of additional lesions might be helpful.

Malignant mesothelioma [see Chap. 13] can often have a papillary pattern, but it usually coexists with other architectural patters (tubular and solid) that are not typical features of serous implants. The stroma may show prominent myxoid change. Presence of intracytoplasmic and extracellular mucoid material may be helpful in ruling out a serous tumor.

HGSC shows marked nuclear pleomorphism and numerous mitotic figures, in contrast to the mild to moderate nuclear atypia and low mitotic activity of SBT/APST implants.

Psammomatous calcifications with no viable tumor cells should be communicated to the surgeon as such. Additional sampling of any clinically suspicious mass lesions may be helpful to reveal epithelial tumor cells.

Lymph Node Involvement by Serous Tumors

Microscopic features

Epithelial cells forming papillary or glandular structures within the lymph node, histologically similar to the primary ovarian SBT/APST or LGSC (Fig. 8.13).

Fig. 8.13

Lymph node involvement by SBT/APST. Note the papillary epithelial clusters of eosinophilic epithelial cells (a) with noticeable nuclear atypia (b)

Papillary architecture with proliferation and tufting.

Cytological atypia.

Psammomatous calcifications are common.

Epithelial cells—single or in small clusters—with nuclear atypia and abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm.

Differential diagnosis

Endosalpingiosis

Endometriosis

Benign mesothelial inclusions

Metastatic carcinoma

HGSC

Other gynecologic or non-gynecologic primaries

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

Endosalpingiosis consists of simple benign glands lined by a single layer of columnar, tubal-type epithelium. No epithelial proliferation, tufting, or atypia is seen. Calcifications may be present (Fig. 8.14).

Fig. 8.14

Endosalpingiosis in lymph nodes (a, b). Note simple, small glands lined by a single layer of columnar, tubal-type epithelium without epithelial proliferation, tufting, or atypia

May be located in the lymph node capsule or within the parenchyma

Distinction between metastatic carcinoma and involvement by SBT/APST or LGSC may be difficult on frozen section if the tumor focus is small; additional tissue samples and comparison with the primary (ovarian) lesion may be helpful.

Clinical history of previous gynecologic and non-gynecologic primaries and morphologic comparison with the patient’s previous material (if available) may offer important diagnostic clues

High-Grade Serous Carcinoma (HGSC)

Clinical features

Most common type of ovarian carcinoma

Mean patient age: late 50s to early 60s

Over 90 % of cases present at an advanced stage

Majority of cases are bilateral

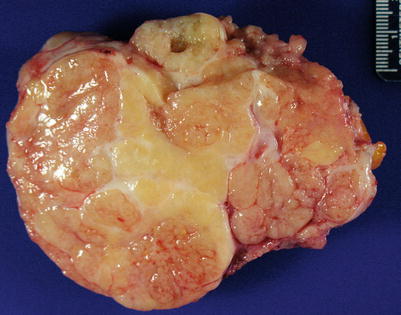

Gross pathology (Fig. 8.15)

Fig. 8.15

High-grade serous carcinoma on gross examination may be a partially cystic mass lesion with intracystic papillary growth (a) or predominantly solid with areas of necrosis and hemorrhage (b)

Size ranges from <1 to 20 cm.

May be entirely solid or partially cystic with a solid component.

Ovarian surface is frequently irregular, grossly involved by tumor.

Cut surface often shows hemorrhage and necrosis.

May show intracystic papillary growth pattern.

Sampling of one or two blocks from the solid or papillary viable tumor areas is usually sufficient for frozen section.

Sampling of grossly obvious foci of necrosis and hemorrhage should be avoided.

Microscopic features (Figs. 8.16 and 8.17)

Fig. 8.16

High-grade serous carcinoma. Note the variety of microscopic growth patterns: complex glandular pattern with slit-like spaces (a), papillary (b), undulating epithelial cell “ribbons” (c), and solid sheets of tumor cells (d)

Fig. 8.17

High-grade serous carcinoma, high magnification. Marked nuclear atypia, brisk mitotic activity with atypical mitoses (a, arrow; b), desmoplastic reaction (c), and necrosis (d) are characteristic

Usually an admixture of various morphologic patterns: solid, complex glandular with slit-like spaces, cribriform, and papillary.

Rarely may show predominant or exclusive papillary pattern.

Undulating bands of epithelial cells resembling transitional cell carcinoma may be seen.

Stromal desmoplastic response may be present.

Marked nuclear atypia with prominent, eosinophilic nucleoli.

Multinucleated tumor cells and bizarre pleomorphic nuclei.

High mitotic activity with atypical mitotic figures.

Necrosis in small or large confluent foci.

Psammomatous calcifications are common.

Cytoplasmic vacuolization may be present.

Differential diagnosis

SBT/APST

LGSC

Other Mullerian (gynecologic) carcinomas:

Endometrioid adenocarcinoma, clear cell carcinoma, malignant Brenner tumor, carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed Mullerian tumor)

Malignant germ cell tumors (MGCT)

Metastatic tumors (gastrointestinal, breast)

Malignant mesothelioma, with papillary pattern

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

Two most important issues regarding the intraoperative diagnosis:

Recognize the tumor as a high -grade epithelial malignancy.

Rule out metastasis from other—non-gynecologic—primaries.

Rarely HGSC may show a predominant papillary growth pattern without obvious stromal invasion, mimicking SBT/APST. However, unlike SBT/APST, HGSC displays marked nuclear atypia and high mitotic activity.

While the architectural features of HGSC may mimic LGSC on low-power examination, higher magnification shows the obvious differences in nuclear atypia and mitotic index.

The distinction between HGSC and other high-grade carcinomas of Mullerian origin (e.g., endometrioid and clear cell carcinoma, malignant Brenner tumor) is usually not critical on intraoperative sections. Frozen section diagnosis can be communicated to the surgeon as “high-grade carcinoma, consistent with Mullerian primary.”

HGSC arising from the fallopian tube or peritoneum is morphologically identical to HGSC of ovary—distinction between these primary sites is not critical for intraoperative management.

Metastatic endometrial serous carcinoma also shares the morphologic features of ovarian HGSC, but it is usually not crucial for intraoperative management to distinguish between the two primaries.

Mucinous tumors: HGSC may show intracytoplasmic vacuoles raising the possibility of mucinous differentiation. In addition, intraluminal necrosis can mimic the type of “dirty necrosis” often seen in metastatic colon adenocarcinomas. It is helpful to find areas (multiple sections may be submitted if necessary) with papillary and slit-like glandular architecture, psammomatous calcifications, and bizarre, markedly atypical nuclei to establish the diagnosis of HGSC.

MGCTs typically present at a much younger age (children or young adults), than HGSC.

Metastatic tumors (gastrointestinal and breast).

Clinical history and morphologic comparison of patient’s previous material (if available) are most helpful.

Papillary and slit-like glandular architecture and psammomatous calcifications, although not entirely specific for HGSC, are less often seen in metastatic tumors of the ovary.

Malignant mesothelioma, with papillary pattern [see Chap. 13].

Malignant mesothelioma can closely mimic HGSC. however, it generally has more uniform tumor cells, with lesser degree of nuclear atypia (mild to moderate), and the mitotic activity is not as high as that of HGSC. Psammomatous calcifications may be seen in both tumors.

Mucinous Ovarian Tumors

Mucinous Cystadenoma

Clinical features

Most common ovarian mucinous tumor

Wide patient age range; mean 50 years [6]

Commonly presents with pelvic pain and/or mass

Typically unilateral (95 %)

Gross pathology (Fig. 8.18)

Fig. 8.18

Mucinous cystadenoma often appears as a uni- or multiloculated cyst on gross examination

Size may vary from 1 to >30 cm (mean 10 cm).

Smooth ovarian surface.

Cystic, uni- or multilocular cut surface.

Rarely may be entirely or partially solid—mucinous adenofibroma or due to associated Brenner tumor or mature teratoma

Cyst contents are viscous, glistening mucoid material.

Appearance of cyst contents may be helpful to form an initial impression, but only the type of epithelial lining is used in the final histological classification

Mucinous tumors often show significant morphologic heterogeneity; therefore, multiple areas should be sampled for frozen section for adequate assessment.

Microscopic features (Figs. 8.19, 8.20, and 8.21)

Fig. 8.19

Mucinous cystadenoma is lined by a single layer of nonstratified mucinous epithelium, resembling gastric foveolar-type (a) or intestinal-type epithelium with goblet cells (b)

Fig. 8.20

Mucinous cystadenoma. The tumor may show invaginations of the cyst lining and have an adenofibromatous appearance (a). Focal epithelial proliferation comprising less than 10 % of tumor may also be seen (b, right lower corner). Acellular mucin in the ovarian stroma (pseudomyxoma ovarii) can be associated with mucinous cystadenoma (c, lower portion of image)

Fig. 8.21

Seromucinous cystadenoma (Mullerian-type mucinous cystadenoma). Note the admixture of serous (eosinophilic) and mucinous (endocervical-type) epithelial cells

Epithelial lining is simple, nonstratified, most commonly resembling gastric foveolar-type or intestinal-type epithelium with goblet cells.

Epithelium may be undulating or may form filiform papillae with fibrovascular cores.

Nuclei are basally located, small, uniform without significant atypia.

Abundant slightly basophilic cytoplasm.

Low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio.

Mitotic figures are rare or absent.

Invaginations of cyst lining into ovarian stroma are not uncommon and should not be mistaken for epithelial complexity or invasion.

“Spillage” of acellular mucin into the ovarian stroma may be seen (“pseudomyxoma ovarii”) and may be associated with histiocytic response.

Less commonly seromucinous (previously also termed endocervical-type or Mullerian-type) lining may be seen with variable admixture of serous and mucinous (endocervical-type) epithelial cells.

Seromucinous tumors are often associated with endometriosis.

Intestinal-type mucinous cystadenomas may be associated with Brenner tumor or mature teratoma.

Differential diagnosis

Other benign cystic entities—serous cystadenoma, follicular cyst, simple cyst, and endometriotic cyst

Mucinous cystadenoma with focal epithelial proliferation/atypia (<10 % of tumor)

Mucinous borderline tumor (MBT)/atypical proliferative mucinous tumor (APMT)

Epithelial proliferation and atypia is present in >10 % of the tumor.

Metastatic mucinous carcinomas

Diagnostic pitfalls/key intraoperative consultation issues

Distinction between benign mucinous cystadenoma and other benign cysts should be made on frozen section if possible. If the frozen section diagnosis indicates a mucinous ovarian tumor (even benign mucinous cystadenoma), the surgeon may survey the appendix intraoperatively and may elect to perform appendectomy to rule out the possibility of an appendiceal primary.

Distinction between intestinal and seromucinous subtypes of mucinous cystadenoma is not critical on frozen sections.

Tangential sectioning of epithelium or invaginations of cyst lining into ovarian stroma may mimic epithelial proliferation.

Mucinous cystadenoma with focal proliferation and atypia (<10 % of epithelial lining shows proliferation or atypia) [5, 17].

Does not meet criteria for MBT/APMT; no staging surgery is necessary.

Additional frozen section sampling may be helpful.

Surgeon may be advised that additional sampling for permanent sections could increase the percentage of atypical proliferation, especially in large tumors.

Metastatic mucinous carcinoma.

Rarely metastatic mucinous tumors from appendiceal, pancreatobiliary, and endocervical primaries can mimic benign mucinous ovarian cystadenoma (“maturation phenomenon”), especially on limited frozen section sampling

Bilaterality, small size (<10 cm) and ovarian surface involvement strongly favor metastasis [18, 19]

The surgeon should be inquired about:

Patient’s clinical history of prior malignancies

Any concurrent mass lesions/imaging findings

Intraoperative findings

Mucinous Borderline Tumor (MBT)/Atypical Proliferative Mucinous Tumor (APMT)

Clinical features

Wide age range with a mean age in 40s.

Almost always unilateral (intestinal-type MBT/APMT).

Seromucinous MBT/APMT may be bilateral in up to 40 % of cases.

Almost always limited to the ovary.

Excellent prognosis, >99 % overall survival [6].

Gross pathology (Fig. 8.22)

Fig. 8.22

Mucinous borderline tumor (MBT)/atypical proliferative mucinous tumor (APMT) typically shows a multiloculated cystic cut surface with viscous/mucinous cyst contents (a, b)

Size may be up to 50 cm, mean: 21.5 cm [20].

Smooth external surface.

Multiloculated, cystic cut surface and viscous mucoid cyst contents.

Solid component is uncommon and should raise concern for carcinoma or mural nodule.

Inking of ovarian surface (at least in the area where frozen sections are submitted from) is helpful in determining surface involvement.

Mucinous tumors often show significant morphologic heterogeneity; therefore, multiple areas—up to 3–4 tissue blocks—should be sampled to adequately assess the tumor on frozen section.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree