Ovarian Endometrioid, Clear Cell, Transitional, and Mixed Epithelial–Stromal Tumors

Endometrioid Tumors

Endometrioid tumors of the ovary resemble those encountered more frequently in the endometrium.1,2 They include endometrioid carcinomas, endometrioid stromal sarcomas, adenosarcomas, and malignant mesodermal mixed tumors (carcinosarcomas). Endometrioid carcinomas are the most common. Although an origin from endometriosis can be demonstrated in some cases, it is not required for the diagnosis (almost all müllerian tumors can originate from endometriosis).1,2 Recent molecular genetic studies, however, suggest that most endometrioid cancers are caused by the malignant transformation of endometriosis and do not derive from the ovarian surface epithelium.3–6

The epithelial cells of endometrioid tumors resemble those of proliferative endometrium. Diastase–periodic acid–Schiff (PAS) and mucicarmine staining reveal some extracellular mucin plus staining of the luminal glycocalyx. Ten percent of tumors contain argyrophil cells of neuroendocrine type. Secretory changes similar to those seen in postovulatory endometrium are frequently seen in well-differentiated tumors and squamous elements are common. Most ovarian endometrioid carcinomas are moderately or well-differentiated tumors with a predominantly glandular or papillary architecture. Presently, the poorly differentiated carcinomas tend to be classified as high-grade serous carcinomas, suggesting that high-grade endometrioid carcinoma is not a distinct tumor type.7 The Systematized Nomenclature of Medicine (SNOMED) classification of endometrioid tumors is as follows:

Epithelial Tumors

Clinical Features

Endometrioid epithelial tumors represent 2–4% of all ovarian tumors.2 Benign endometrioid tumors (mostly adenofibromas) are rare and account for <1% of benign ovarian tumors. Only 2–3% of borderline ovarian tumors are endometrioid. Endometrioid carcinomas account for 10–15% of ovarian carcinomas, representing the second most common form of ovarian epithelial malignancy;2 however, when strict criteria are used (i.e., close resemblance to uterine endometrioid carcinoma and reclassification of nonspecific high-grade carcinomas as serous carcinomas), the frequency falls to <10%.

Benign, borderline, and malignant endometrioid epithelial tumors occur most commonly in women in the perimenopausal or postmenopausal age groups, with mean ages of 56, 51, and 56 years, respectively.2 Most patients with borderline endometrioid tumors have endometriosis (63%) and concomitant endometrial hyperplasia/carcinoma is common (39%).8 Similarly, about 40% of the endometrioid carcinomas are associated with documented ipsilateral ovarian or pelvic endometriosis.2,9 Patients whose tumors are accompanied by endometriosis are 5–10 years younger on average than patients without associated ovarian endometriosis.2,10,11 Endometriosis-related ovarian carcinomas are more frequently low grade and low stage and have a more favorable prognosis than carcinomas unrelated to endometriosis.12 Endometrioid carcinomas are confined to the ovaries and adjacent pelvic structures in 70% of cases. They are bilateral in 28% of all cases and in 13% of those in International Federation of Gynecologists and Obstetricians (FIGO) stages I–II.

Endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary is associated in 15–20% of cases with carcinoma of the endometrium.2,13 The favorable outcome in those cases in which the tumor is limited to both organs suggests that these are mostly independent primary tumors arising as a result of a müllerian field effect or due to implantation of endometrial stem cells carrying genetic abnormalities.13–15 The criteria for distinguishing ovarian metastasis, uterine metastasis, and independent primary tumors of both organs are presented in the following sections.

Like most ovarian carcinomas, many endometrioid carcinomas are asymptomatic. Some present as a pelvic mass with or without pain, and may be associated with endocrine symptoms secondary to steroid hormone secretion by the specialized ovarian stroma.16 Serum CA125 is elevated in over 80% of the cases.17

Pathogenesis

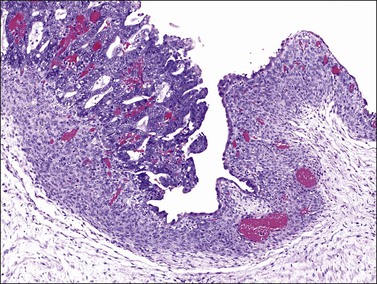

The frequent association of ovarian endometrioid carcinomas with endometriosis, endometrial carcinoma, or both, suggests that some ovarian endometrioid carcinomas may have the same risk factors for their development as endometrial carcinomas. Up to 42% of the endometrioid carcinomas are associated with ipsilateral ovarian or pelvic endometriosis,10 an entity in which the entire spectrum of endometrial hyperplasia can be seen18 (see Chapter 22). Several epidemiologic studies have shown that ovarian endometriosis is associated with an increased risk of developing ovarian endometrioid and clear cell carcinomas (CCCs)9,12,19,20 and a direct transition from ovarian atypical endometriosis to carcinomas has been described in 15–32% of cases11 (Figure 27.1). Atypical ipsilateral endometriosis occurs in up to 23% of endometrioid carcinomas and may have a role in the process of transformation to malignancy.11,18 Occasionally, however, the lining epithelium of endometriotic cysts shows large cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and large, hyperchromatic, smudgy nuclei. This cytologic change is often seen in the absence of carcinoma and its malignant potential is unknown.21

In cases of ovarian endometrioid carcinoma associated with endometriosis, common genetic alterations have been encountered in the adjacent endometriosis, atypical endometriosis, and adenocarcinoma.4 In mice harboring K-RAS mutations that result in the development of benign lesions reminiscent of endometriosis, deletion of PTEN leads to the induction of invasive endometrioid carcinoma.22 Recently, AT-rich interactive domain 1A (ARID1A) gene mutations have been discovered in endometrioid carcinomas and CCCs as well as in adjacent endometriosis.23 These findings indicate that inactivation of tumor suppressor genes such as PTEN or ARID1A may represent early events in the malignant transformation of endometriosis.6

Benign Endometrioid Tumors

The rare endometrioid cystadenomas are similar to endometriotic cysts but lack endometrial stroma, hemosiderin-laden macrophages, and a myofibroblastic wall. Nevertheless, their frequent merging with endometriotic cysts suggests that a pure endometrioid cystadenoma may not even exist. Adenofibromas have non-mucinous glands lying within an abundant fibromatous stroma. Tall columnar epithelium resembles that of proliferative endometrium, with basophilic to deeply eosinophilic cytoplasm and elongate nuclei with relatively coarse chromatin and small but obvious nucleoli, or inactive endometrium with uniform dark nuclei and scanty cytoplasm. Mitoses are rarely seen. Squamous differentiation in the form of morules is a common finding.1,2

Borderline Endometrioid Tumors

Pathologic Features

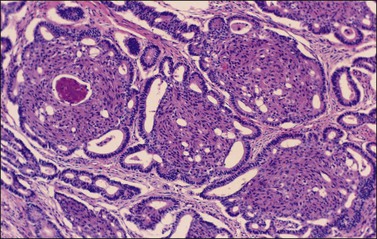

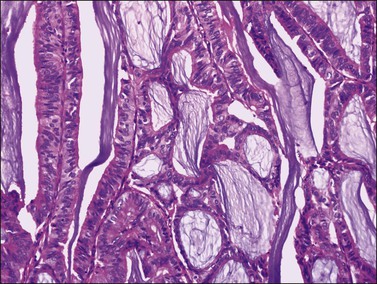

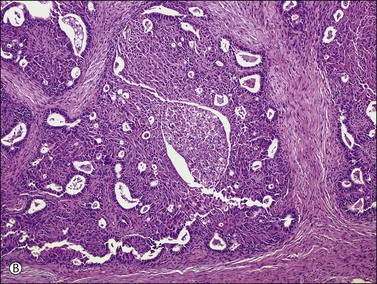

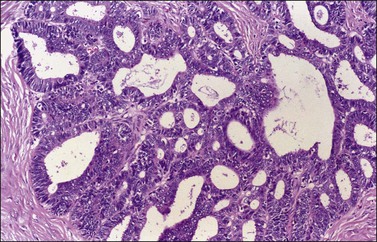

There is no agreement on the criteria for the diagnosis of borderline endometrioid tumors. Most are adenofibromatous and show crowded endometrial-like glands and cystic spaces embedded in stroma that varies from ovarian to hyaline or collagenous (Figure 27.2). The second most common pattern is villoglandular or papillary with an atypical cell lining similar to atypical hyperplasia of the endometrium also in a fibromatous background. By World Health Organization (WHO) criteria, these tumors exhibit glands or cysts lined by atypical or cytologically malignant endometrioid-type cells without obvious stromal invasion (Figure 27.3).1 Mitoses range up to 4 mitotic figures per 10 HPF but are rarely atypical. Squamous metaplasia, present in one-third to one-half of cases, may be occasionally both florid (Figure 27.4) and keratinizing. It may give rise to a foreign body giant cell reaction. Stromal luteinization occasionally occurs. An uncommon stromal change is focal metaplastic benign bone formation. When the epithelial component is carcinomatous the term borderline endometrioid tumor with intraepithelial carcinoma is used and the tumor is graded 1–3 (Figure 27.3). Microinvasion is arbitrarily defined as the presence of one or more foci of epithelial cells haphazardly infiltrating the stroma, 10 mm2 or less in area.2 Tumors exhibiting confluent glandular growth (5 mm or more in maximum diameter) and destructive stromal invasion greater than microinvasion are diagnosed as invasive carcinomas. Cytologic atypia and microinvasion do not appear to affect the favorable prognosis of borderline endometrioid tumors and conservative treatment, i.e., unilateral salpingo-oophorectomy, appears to be curative. However, only 134 cases have been reported and clinical follow-up data are limited.8,24

Figure 27.2 Borderline endometrioid adenofibroma. (A) Crowded endometrial-like glands and cystic spaces are embedded in dense fibrous stroma. (B) The squamous differentiation confirms the endometrioid nature of the tumor.

Figure 27.3 Borderline endometrioid adenofibroma with well-differentiated (grade 1) intraepithelial carcinoma. Island of crowded glands with cribriform pattern and moderate nuclear atypia without obvious stromal invasion.

Immunohistochemistry and Somatic Genetics

The immunohistochemical profile of borderline endometrioid tumors resembles that of endometrioid carcinomas (see later). In both, β-catenin gene mutation appears to be an early event in tumorigenesis.25 In a study of eight borderline endometrioid tumors, a strong nuclear β-catenin immunoreaction (in both, the glandular and squamous components) was obtained in all cases, and seven (90%) had β-catenin gene (CTNNB1) mutations. Only one tumor had a PTEN mutation. Neither K-RAS mutations nor microsatellite instability were encountered.

Endometrioid Carcinomas

Macroscopic Features

Endometrioid carcinomas are predominantly cystic, measuring 12–20 cm in diameter, with usually smooth outer surfaces. The cut surfaces reveal friable soft masses or papillae partly filling cystic spaces that may contain blood-stained fluid. Rarely, they are completely solid, exhibiting hemorrhage or necrosis. Mucus may sometimes fill the cystic spaces. The tumor, if it has arisen in an endometriotic cyst, tends to be a polypoid nodule projecting into the lumen of a thick-walled blood-filled cyst (Figure 27.5).

Microscopic Features

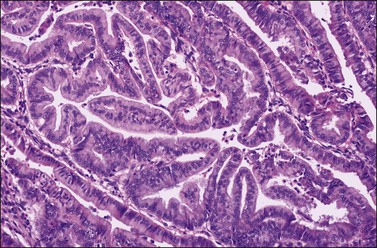

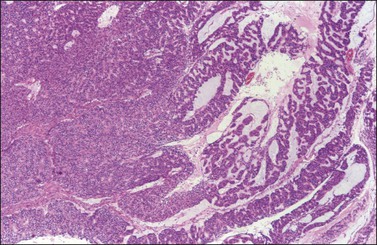

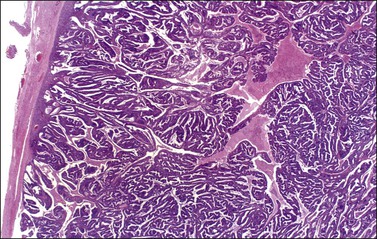

Ovarian endometrioid carcinomas closely resemble endometrioid carcinomas of the uterine corpus. Most tumors show confluent glandular proliferation or ‘expansile invasion.’26 There is back-to-back arrangement of the glands with reduction of the stroma, glandular branching, cribriform pattern, and complex papillary proliferation (Figure 27.6). Less frequently, the tumors exhibit destructive infiltrative growth characterized by obvious stromal invasion in the form of glands, cell clusters, or individual cells, disorderly infiltrating the stroma and frequently associated with a desmoplastic or inflammatory stromal reaction.26

Figure 27.6 Well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma (grade 1). The tumor shows a villoglandular pattern.

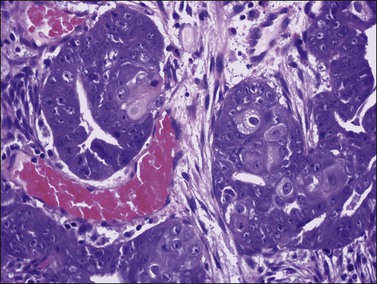

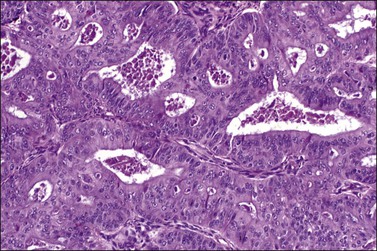

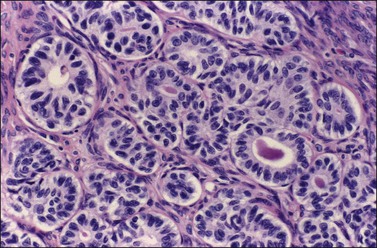

Most endometrioid carcinomas are well differentiated—particularly those arising from endometriotic cysts—and show round, oval, or tubular glands lined by stratified non-mucin-containing epithelium (Figure 27.7). Mitoses range up to about 5 per 10 HPF. Cribriform or villoglandular patterns may be present (Figure 27.8). The broad blunt papillae with obvious connective tissue cores differ from the usually fine micropapillae of serous carcinomas. Squamous differentiation occurs in 30–50% of the cases, often in the form of morules (cytologically benign-appearing squamous cells) (Figure 27.9).2 Occasionally, the squamous elements appear malignant and are then intimately admixed with or separated from the glandular component. The current designation ‘endometrioid carcinoma with squamous differentiation’ is generally preferable to the adenoacanthoma or adenosquamous carcinoma, even though the latter terms in many cases more succinctly convey the degree of histologic differentiation of the squamous epithelium.1,2 Aggregates of spindle-shaped epithelial cells are an occasional finding in endometrioid carcinoma (Figure 27.10).27 Rarely, the spindle cell nests undergo a transition to clearly recognizable squamous cells, suggesting that the former may represent abortive squamous differentiation.27 Some well-differentiated endometrioid carcinomas, almost always with a squamous component, may have a prominent fibrous stroma (malignant adenofibromas). Stromal invasion in such tumors is difficult to document and inferred only by the extent and complexity of the glandular component and the presence of a desmoplastic stroma.

Figure 27.7 Endometrioid adenocarcinoma. The crowded neoplastic glands are lined by stratified non-mucin-containing epithelium. Nuclear atypia is moderate.

Figure 27.10 Endometrioid adenocarcinoma with spindle-shaped epithelial cells. The spindle-shaped cells merge almost imperceptibly with the glandular epithelium (abortive squamous differentiation).

Rare examples of mucin-rich (Figure 27.11), secretory, ciliated cell, and oxyphilic types have been described.28,29 In the mucin-rich variant, glandular lumens and apex of the cell cytoplasm are occupied by mucin.30 Minor foci of mucinous epithelium are present in some endometrioid carcinomas and should not lead to the diagnosis of mucinous carcinoma. The secretory type contains vacuolated cells with supranuclear and/or subnuclear vacuoles resembling those of an early secretory endometrium.2 Hobnail cells are not seen. The oxyphilic variant has a prominent component of large polygonal tumor cells with abundant eosinophilic cytoplasm and round central nuclei with prominent nucleoli.29

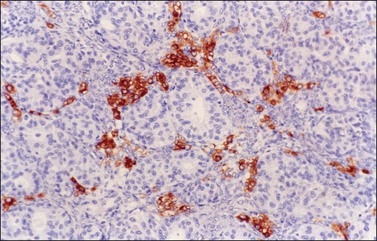

Occasional tumors contain solid areas punctuated by tubular or round glands or small rosette-like glands (microglandular pattern) simulating an adult granulosa cell tumor.31 Unlike the Call–Exner bodies found in granulosa cell tumors, the microglands in endometrioid carcinomas contain intraluminal mucin. The nuclei of endometrioid carcinomas are usually round and hyperchromatic, whereas those of granulosa cell tumors are round, oval, or angular, pale, and grooved31 (see Chapter 28). Rare cases of endometrioid carcinomas of the ovary show focal to extensive areas resembling Sertoli and Sertoli–Leydig cell tumors (Figures 27.12 and 27.13)31–33 They contain small, well-differentiated hollow tubules, solid tubules or, rarely, thin cords resembling sex cords. Furthermore, the stroma may appear cellular and fibrous, resembling the spindle cell component of stromal tumors. When the stroma is luteinized (Figure 27.14), this variant (designated as ‘endometrioid carcinoma resembling sex cord–stromal tumor’ or ‘sertoliform endometrioid carcinoma’) may be mistaken for a Sertoli–Leydig cell tumor, particularly if the patient is virilized. However, typical glands of endometrioid carcinoma and squamous differentiation are each present in 75% of the tumors, facilitating their recognition as an endometrioid carcinoma.31 Furthermore, immunostains for α-inhibin (Figure 27.15) and calretinin show reactivity in the luteinized stromal cells and Sertoli cells but not in the cells of endometrioid carcinoma.34 At surgery, most of these tumors are confined to the ovary (FIGO stage I).

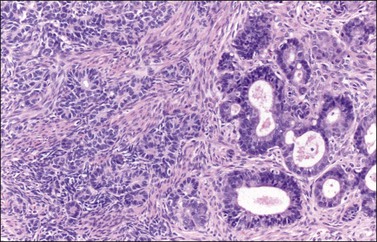

Figure 27.12 Endometrioid adenocarcinoma resembling a Sertoli cell tumor. Tubular glands lined by cells with oval nuclei and clear cytoplasms, resembling the tubules of a Sertoli cell tumor.

Figure 27.13 Endometrioid adenocarcinoma resembling a Sertoli cell tumor. The small tubular glands, resembling the tubules of a Sertoli cell tumor (left), appear adjacent to typical glands of endometrioid carcinoma (right).

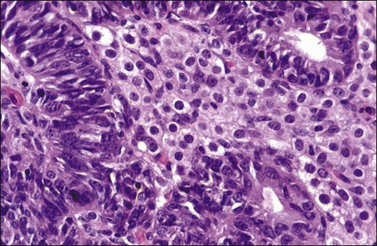

Figure 27.14 Endometrioid adenocarcinoma resembling a Sertoli–Leydig cell tumor. The tubular glands contain high-grade nuclei. The luteinized ovarian stromal cells resemble Leydig cells.

Figure 27.15 Endometrioid adenocarcinoma resembling a Sertoli–Leydig cell tumor. Immunoreaction for α-inhibin is positive in the luteinized stromal cells and negative in the epithelial cells.

Rarely, endometrioid carcinomas may exhibit an adenoid basal or adenoid cystic-like component35 (Figure 27.16). Recently, endometrioid carcinomas with transitional cell-like differentiation have been reported.36 More rarely, endometrioid carcinomas may contain yolk sac tumor elements. These tumors are often large and have an unfavorable prognosis.37,38 Immunoreactions for α-fetoprotein (AFP) and glypican-3 are strongly positive in the yolk sac tumor component.

Most well-differentiated endometrioid adenocarcinomas contain areas of endometriosis, endometrioid adenofibroma, or borderline endometrioid tumor.26,39

Poorly differentiated endometrioid carcinomas are rare and have a predominantly solid pattern with focal microglandular areas. Mitotic activity is high (up to 5 or more mitoses per HPF) and squamous or secretory change infrequent. Hemorrhage and/or necrosis are prominent. However, most high-grade carcinomas with these features would be currently classified as serous carcinomas.40

Sometimes, ovarian carcinomas with a predominantly endometrioid component are mixed with other epithelial types such as clear cell and serous carcinoma. A mixed epithelial tumor is diagnosed when 10% or more of a second or third type of epithelium is present.1

Immunohistochemistry

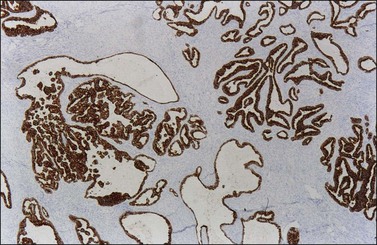

Endometrioid carcinomas react strongly with epithelial markers including cytoplasmic immunoreaction for cytokeratins (CK7, 97%; CK20, 13% positive) (Figure 27.17) and membranous reaction for epithelial membrane antigen (EMA). The rate of immunoreactivity for other markers is as follows: vimentin, 31%; B72.3, 86%; OC-125, 76%; and carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA), 30%. Estrogen receptors (ERs) and progesterone receptors (PRs) are positive in the majority of cases.41 WT1 and p16 are usually negative42,43 but WT1 can be positive in 17–29%44–47 and focal p16 immunoreactivity can occur in up to half of cases.44 BRCA1 protein is usually positive (nuclear reaction).48 Inhibin is usually negative,34,49 but calretinin is strongly positive in 10%, and weakly positive in an additional 10–25%.45,50 CD99 is often positive. PTEN expression is negative in well-differentiated carcinomas; however, PTEN immunoreaction is unreliable.51 Most tumors with microsatellite instability, approximately 10–15% of ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinomas,52 show negative immunoreaction for hMLH1 and hMSH2 proteins.53 Strong and diffuse immunoreactivity for p53 should raise the differential diagnosis of high-grade serous carcinoma.

Grading

Grading of endometrioid carcinoma of the ovary uses the same criteria as for endometrial adenocarcinoma54 (see Chapter 18). Grade I tumors are glandular or papillary neoplasms exhibiting <5% of solid tumor growth (Figure 27.6). Grade II tumors show 5–50% solid growth, and grade III tumors show >50% solid tumor growth (Figure 27.18). Areas of squamous or spindle cell differentiation are not counted as solid growth. When the nuclei are highly atypical and the architectural glandular pattern is grade I or II, the overall tumor grade is increased by one. Most ovarian endometrioid carcinomas are well differentiated, and show low-grade nuclei. Thus, nuclear grade is the best discriminator.

Spread and Metastasis

Stage I carcinomas are bilateral in 17% of the cases. The stage distribution of endometrioid carcinomas differs from that of serous carcinomas. According to the FIGO annual report, 31% of the tumors are stage I, 20% stage II, 38% stage III, and 11% stage IV.55 However, in a review of 874 cases from 19 series, 43% of the tumors were stage I.24

Genetic Susceptibility

Most endometrioid carcinomas occur sporadically but occasional cases develop in families with germline mutations in DNA mismatch repair genes, mainly MSH-2 and MLH-1 (Muir–Torre syndrome).56 This syndrome, a variant of the hereditary nonpolyposis colorectal cancer (HNPCC) syndrome, reflects an inherited autosomal dominant susceptibility to develop cutaneous and visceral neoplasms.57

Somatic Genetics

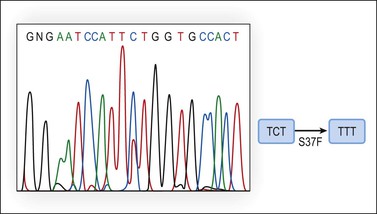

The molecular genetic alterations of well-differentiated ovarian endometrioid carcinomas are similar to those of their uterine counterparts. Compared with uterine endometrioid carcinomas, the ovarian tumors have similar frequency of β-catenin abnormalities but a lower rate of microsatellite instability and PTEN alterations.52 β-catenin protein, encoded by the CTNNB1 gene located in 3p21, maintains cell polarity by interacting with E-cadherin at the cell membrane. In the cytoplasm, free β-catenin interacts with the adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) protein and may function as a transcription factor. The APC protein downregulates β-catenin by cooperating with the glycogen synthase kinase 3-β (GSK-3-β), inducing phosphorylation of the serine–threonine residues coded in exon 3 of the CTNNB1 gene and its degradation through the ubiquitin–proteasome pathway. CTNNB1 activating mutations alter recognition sequences and inhibit phosphorylation, resulting in cytoplasmic and nuclear accumulation of β-catenin, signal transduction, and transcriptional activation through the LEF/Tcf pathway. Increased β-catenin expression caused by CTNNB1 or APC mutations results in uncontrolled activation of target genes such as matrix metalloproteinase-7 (MMP-7) and cyclin D1 (CD1). Activating mutations of the CTNNB1 gene occur in 38–50% of ovarian endometrioid carcinomas (Figure 27.19)52,58,59 and nuclear β-catenin immunoreaction is seen in the tumor cells in over 80% of these cases. Endometrioid carcinomas with CTNNB1 mutations often show squamous differentiation, and are low-grade and early stage tumors associated with good prognosis.52,60

Figure 27.19 Endometrioid adenocarcinoma. DNA sequencing of exon 3 of the β-catenin (CTNNB1) gene discloses a TCT to TTT point mutation at codon 37 (S37F).

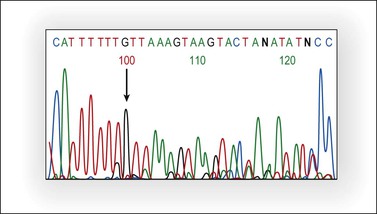

The tumor suppressor gene PTEN is located in chromosome 10q23.3, a genomic region undergoing loss of heterozygosity (LOH) in a wide variety of human cancers. PTEN encodes a lipid phosphatase that antagonizes the PI3K/AKT pathway by dephosphorylating PIP3, the product of PI3K. PI3K is a heterodimer enzyme consisting of a catalytic subunit (p110) and a regulatory subunit (p85).The PIK3CA gene, located on chromosome 3q26.32, codes for the p110 catalytic subunit of PI3K. Decreased PTEN activity causes activation of the PI3K/AKT pathway and expression of several genes involved in suppression of apoptosis and cell cycle progression. PTEN may be inactivated by several mechanisms such as mutation, LOH at 10q23, and promoter hypermethylation. Loss of function of the two alleles is needed for PTEN inactivation and, usually, mutation and LOH coexist. PTEN is mutated in approximately 20% of endometrioid ovarian tumors (Figure 27.20) and in 46% of those with 10q23 LOH.5,52 PTEN mutations occur between exons 3 and 8. The majority of endometrioid carcinomas with PTEN mutations are well-differentiated and stage I tumors, suggesting that PTEN inactivation is an early event in this subset of ovarian tumors.5,52,60 The finding of 10q23 LOH and PTEN mutations in endometriotic cysts that are adjacent to endometrioid carcinomas with similar genetic alterations provides additional evidence for the precursor role of endometriosis in ovarian carcinogenesis.6

Figure 27.20 Endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Partial representative nucleotide sequencing of antisense strand around the (A) 6 tract in exon 8 of PTEN. Sequence analysis of polymerase chain reaction (PCR) product of tumor DNA showed the deletion of one nucleotide in the poly-A tract.13 (Reproduced with permission from Irving et al.13)

PIK3CA mutations, mainly clustered in exons 9 and 20, have been identified in up to 20% of ovarian endometrioid carcinomas but in only 2% of serous carcinomas.61 In some tumors, PIK3CA and PTEN mutations co-occur and an additive effect on the PI3K pathway has been suggested.62 In both the ovary and the endometrium, PIK3CA mutations are associated with adverse prognostic parameters.63

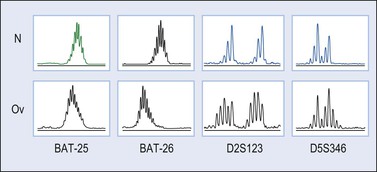

Microsatellites are repetitive DNA sequences usually one to five nucleotides in length. Microsatellite instability refers to alterations in the DNA of tumor cells in which the number of sequence repeats in these microsatellites differs from the number of repeats at the same locus in DNA from the patient’s normal cells. Microsatellite instability has been found in 12–20% of ovarian endometrioid carcinomas.52,58,64 Cancer patients from HNPCC kindreds have an inherited germline mutation either in MLH-1, MSH-2, MSH-6, or in PMS-2 (‘first hit’) and carcinoma develops after the instauration of a deletion or mutation in the contralateral allele (‘second hit’).65 In contrast, in sporadic tumors, MLH-1 inactivation by promoter hypermethylation is the main cause of mismatch repair deficiency leading to accumulation of myriads of mutations in coding and non-coding DNA sequences (Figure 27.21).52,58,64 Short-tandem repeats are particularly susceptible to mismatch repair alterations; however, most occur in non-coding DNA sequences and subtle mutations (insertions or deletions) do not result in the production of abnormal proteins. However, some mononucleotide repeats are located within the coding sequence of important genes such as BAX, IGFIIR, hMSH3, hMSH6, MBD4, CHK-1, or caspase-5, which may be potential targets during tumor progression in ovarian endometrioid carcinomas with microsatellite instability.64

Figure 27.21 Endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Microsatellite instability for the loci BAT-25, BAT-26, D2S123, and D5S346 (capillary electrophoresis).

Inactivating mutations of ARID1A, which encodes a subunit of the SWI/SNF chromatin remodeling complex, have been found in 30% of endometrioid carcinomas.23 The mutations are typically frameshift or nonsense mutations that result in loss of protein expression. p53 mutations have been reported in up to 60% of endometrioid carcinomas arising in the ovary, most often in high-grade tumors. However, recent studies indicate that many ovarian tumors previously diagnosed as high-grade endometrioid carcinomas lack the characteristic mutations of low-grade endometrioid carcinoma and have gene expression profiles indistinguishable from high-grade serous carcinomas.

Differential Diagnosis

The distinction of endometrioid tumors from mucinous neoplasms has been discussed in Chapter 26.

1. High-grade serous carcinoma. As indicated above, most ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinomas are low-grade carcinomas that exhibit rounded glands and broad papillae lacking the slit-like spaces typical of high-grade serous carcinomas. Furthermore, not infrequently they show squamous differentiation and an adenofibroma component. In contrast to high-grade serous carcinoma, ovarian endometrioid adenocarcinomas usually fail to react for WT1, are only focally immunoreactive for p16, and show positive PR and vimentin immunoreaction. Nuclear reaction for β-catenin is frequently positive whereas p53 is usually negative.

2. Endometrioid adenofibroma versus Brenner tumor. Both tumors exhibit a prominent fibrous stromal component. Endometrioid tumors generally have an epithelial component in the form of glands with lumens, whereas in Brenner tumors the epithelial component typically consists of branching nests and trabeculae of transitional cells; a glandular component, if present in the Brenner tumor, is frequently mucinous. Nuclear grooves, characteristic of the transitional cells of Brenner tumors, are not found in squamous morules.

3. Endometrioid adenocarcinoma, secretory type, versus clear cell adenocarcinoma. The secretory form of endometrioid adenocarcinoma displays glands lined by well-differentiated cells with basal and supranuclear vacuoles. The tubulocystic pattern of CCC exhibits glands lined by hobnail cells with high-grade nuclei. In addition CCC, unlike secretory carcinoma, usually contains areas where the tumor is composed of sheets of tumor cells with clear cytoplasm.

4. Ovarian tumor of wolffian origin. The glands of endometrioid carcinoma commonly contain intraluminal mucin, which is absent in wolffian tumors. Wolffian tumors are reactive for CD10 but rarely reactive for EMA and B72.3.2

5. Yolk sac tumor (glandular variant). Typically occurs in young women, shows other more common patterns, and exhibits reactivity for AFP and glypican-3 (see Chapter 29). Occasionally, yolk sac differentiation is encountered in endometrioid carcinomas.38

6. Granulosa cell tumor (insular, trabecular, or microfollicular). In contrast to Call–Exner bodies, endometrioid carcinomas contain microglands with intraluminal mucin. Also, the nuclei of endometrioid carcinomas are usually round and hyperchromatic, whereas those of granulosa cell tumors are round, oval, or angular, pale and grooved.31 Carcinomas are reactive for EMA, whereas granulosa cell tumors are reactive for FOXL2, α-inhibin, and calretinin.

7. Sertoli–stromal cell tumors. Most occur at an average age of 25 years and are usually unilateral (bilaterality, 2%). Endometrioid carcinomas are bilateral in about 28% of the cases. Typical endometrioid glands (Figure 27.13) with intraluminal mucin and squamous differentiation are each found in three-fourths of tumors resembling Sertoli–stromal cell tumors.31 α-Inhibin and calretinin are positive in Sertoli cells.34,49

8. Identical patterns of endometrioid carcinoma involving both the ovary and uterine corpus (independent primaries vs metastatic tumors). This problem is discussed later. The good prognosis in cases in which the tumor is limited to both organs provides strong evidence that the neoplasms are independent primaries in most of such cases.13,14 According to FIGO, the primary site of the tumor should be determined by its initial clinical manifestations.55

9. Metastatic colonic adenocarcinoma. This differential diagnosis is covered more fully in Chapter 30. Bilaterality, ‘dirty’ necrosis, amputated glands, desmoplastic stroma, vascular invasion, and ‘too high grade’ nuclei, all favor metastatic carcinoma. In addition, metastatic colonic carcinoma is usually reactive for CK20, CEA, and CDX-2, whereas endometrioid carcinoma is reactive for CK7 (Figure 27.17).

Treatment and Prognosis

The treatment of endometrioid carcinomas is similar to that of ovarian cancers in general. The 5 year survival rate of patients with stage I carcinoma is 78%, stage II 63%, stage III 24%, and stage IV 6%.55 Patients with grade I and II tumors have a higher survival rate than those with grade III tumors. Peritoneal foreign body granulomas to keratin found in cases of endometrioid carcinoma with squamous differentiation do not seem to affect the prognosis adversely in the absence of viable-appearing tumor cells.2 Endometrioid carcinomas with a mixed clear cell, serous, or undifferentiated carcinoma component are reported to have a worse prognosis.67

Simultaneous Endometrioid Carcinomas of the Ovary and Endometrium

Simultaneous carcinomas of the ovary and uterine corpus, usually detected as synchronous and less frequently as metachronous tumors, occur in 15–20% of ovarian tumors and in approximately 5% of uterine tumors.1 Both tumors are of endometrioid type in the majority of cases. Accurate diagnosis, as independent primary tumors or metastases, has important prognostic implications and is necessary for appropriate staging and treatment. Independent primary low-grade endometrioid carcinomas limited to the endometrium and ovary are associated with favorable outcome and require no additional treatment other than oophorectomy and hysterectomy. In contrast, metastatic tumors usually carry an adverse prognosis and adjuvant therapy is indicated.

Assessment of conventional pathologic features including tumor size, histologic type, and grade; pattern of tumor growth; vascular invasion; and coexisting atypical hyperplasia or endometriosis allows the distinction in most cases.1 For example, in cases of low-grade endometrial carcinomas associated with hyperplasia and minimal or no myometrial invasion, the ovarian tumor can safely be regarded as primary, particularly if it shows endometriosis, adenofibroma, or a borderline tumor component. In contrast, bilaterality and multinodular growth, as well as vascular space and tubal invasion, are characteristic features of ovarian metastases. In patients with simultaneous carcinomas, however, the 5 year survival is 70–92%, and the median survival is 10 years or longer;68,69 thus, follow-up favors two independent adenocarcinomas since most patients survive without recurrence.14,70,71

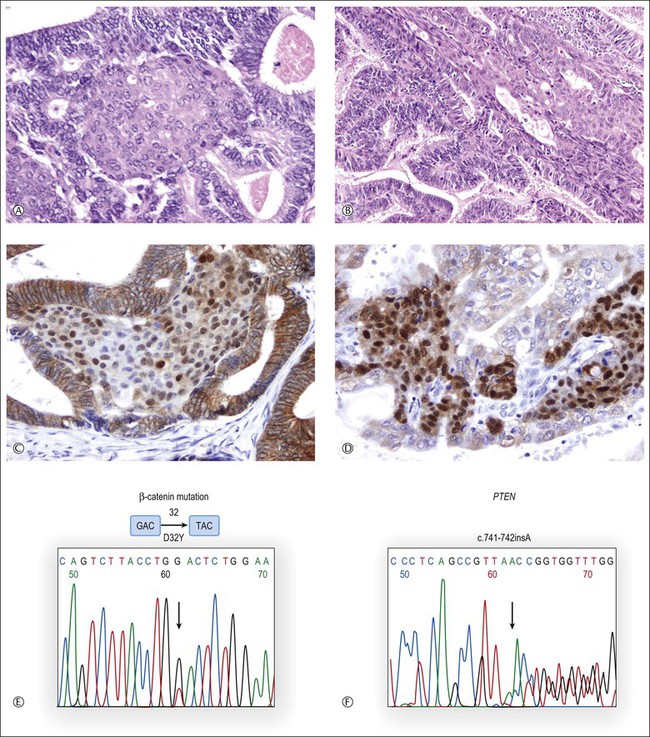

Occasionally, the differential diagnosis can be difficult or impossible as the tumors may show overlapping features.1 Even if patient follow-up is the single most conclusive factor in such cases, ancillary techniques may help to establish the correct diagnosis.13,70,72 Most of the strategies have relied upon the presence or absence of clonal genetic alterations in the ovarian and endometrial adenocarcinomas to identify metastatic or independent primary tumors, respectively. It must be emphasized that the results of these analyses should always be interpreted in the light of the clinicopathologic findings.72–75 Also, it should be kept in mind that independent primary carcinomas may show identical gene mutations (Figure 27.22), reflecting induction of the same genetic abnormalities by a common carcinogenic agent acting in two separate sites of a single anatomic region. Alternatively, the genetic profiles of metastatic carcinomas may differ from those of their corresponding primary tumors as a result of tumor progression. In other words, the genetic profile can be identical in independent tumors and different in metastatic carcinomas.73,75

Figure 27.22 Synchronous, independent primary endometrioid carcinomas of the uterus (left) and ovary (right). Both tumors are grade 1 with squamous differentiation as shown in (A) (uterus) and (B) (ovary). Nuclear accumulation of β-catenin is most prominent in squamous morules (C, uterus; D, ovary). Sequence analysis of exon 3 of CTNNB1 reveals an identical GAC → TAC point mutation (D32Y) in both uterine and ovarian tumors (E). Sequencing histogram of PTEN frameshift mutation (F). An identical bp insertion in exon 7 was detected in both tumors.13 (Reproduced with permission from Irving et al.13)

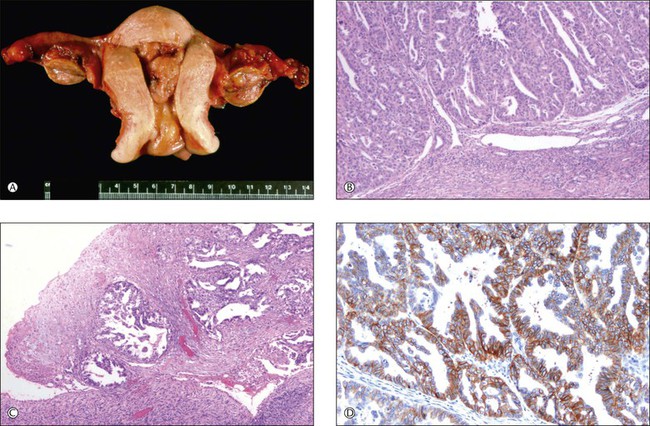

A recent study has revealed a frequency of molecular alterations in both independent and metastatic tumors, including MI and PTEN mutations, which is higher than that observed in single sporadic tumors. Nuclear immunoreactivities for β-catenin and CTNNB1 mutations were restricted to independent uterine and ovarian tumors and were absent in metastatic tumors (Figure 27.23). These findings correlated with the clinical outcome.13

Figure 27.23 Primary endometrioid carcinoma of the uterine corpus with bilateral ovarian metastases. (A) Polypoid tumor filling the endometrial cavity, with surface involvement of both ovaries. (B) The uterine tumor is a minimally invasive (<1 mm) grade 3 endometrioid carcinoma. (C) The ovarian surfaces are extensively involved by metastatic grade 3 endometrioid carcinoma. (D) Membranous pattern of β-catenin immunoreactivity is observed in the uterine tumor (shown) as well as both ovaries and omental metastases.13 (Reproduced with permission from Irving et al.13)

Mixed Tumors (Tumors with a Sarcomatous Component)

Malignant Mesodermal Mixed Tumors (Carcinosarcomas)

These tumors are composed of high-grade carcinoma of different müllerian types and sarcoma. The latter component may be homologous (tissue types native to the müllerian tract, i.e., endometrial stroma, fibrous tissue, and smooth muscle) or heterologous (foreign tissue, such as skeletal muscle, adipose tissue, cartilage, and bone). Any of these various components may be widespread or limited to small foci.1 Approximately one-third fall into the homologous group. Occasionally, these complex neoplasms arise in ovarian endometriosis.

General Features

Malignant mesodermal (müllerian) mixed tumors (MMMTs) account for 2% of all ovarian cancers. They occur in the sixth to eighth decades, and are rare before the age of 40 years.2 Recent immunohistochemical and molecular genetic studies76–78 support a clonal origin of both tumor components (epithelial and mesenchymal-like elements) and, accordingly, a proposal to designate these tumors ‘undifferentiated or metaplastic carcinoma’ has been made.79 However, preserving the currently accepted term MMMT, which indicates the type(s) of neoplastic differentiation, is recommended because of the unique clinicopathologic features of this tumor.

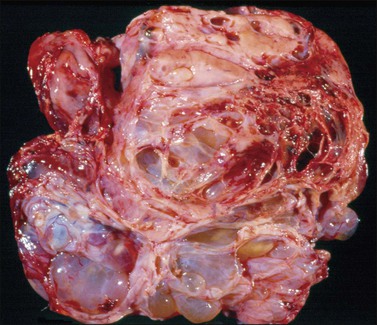

Macroscopic Features

The tumors are bilateral in one-third of the cases.2 They are usually large (15–20 cm mean diameter), friable, solid and/or cystic with areas of necrosis and hemorrhage (Figure 27.24). Occasionally, bone or cartilage can be palpated.

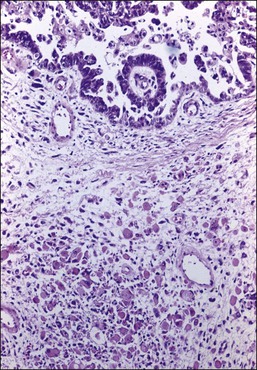

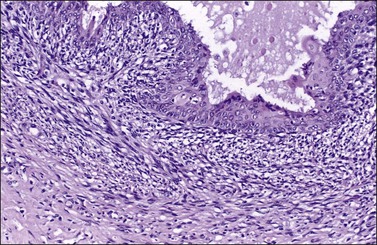

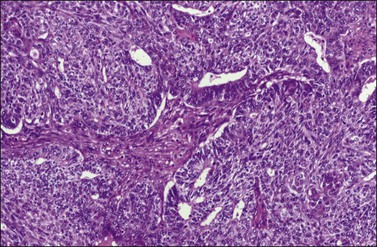

Microscopic Features

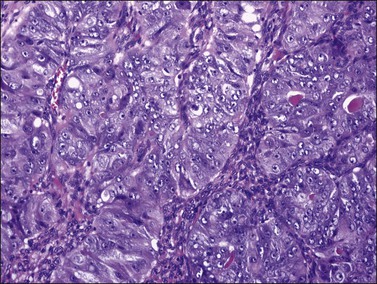

Most tumors display a complex admixture of epithelial and malignant stromal elements and transitions are uncommon. The epithelial component is most frequently high-grade serous (Figure 27.25), endometrioid, or undifferentiated carcinoma. Occasionally, squamous, mucinous, or clear cell carcinoma is found. If the epithelium is mucinous, care should be taken to distinguish such tumors from mucinous cystic tumors with mural nodules (see Chapter 26). The sarcomatous elements are usually hypercellular sheets of small hyperchromatic round to spindle-shaped cells with a high mitotic rate and lacking apparent differentiation. In the homologous type, the sarcoma component resembles fibrosarcoma, malignant fibrous histiocytoma, or high-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. The heterologous tumor most often contains chondrosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma (Figure 27.25), or both. Rarely, osteosarcoma or liposarcoma is present. PAS-positive, diastase-resistant hyaline bodies are common in the sarcoma component. Glial, neuronal, and trophoblastic differentiation may be encountered.

Immunohistochemistry

As a general rule, reactivity for EMA and cytokeratins (AE1/AE3 and CAM5.2) but not for vimentin helps distinguish poorly differentiated carcinoma from sarcoma. However, in MMMTs, the sarcomatous component may also react for cytokeratins and EMA7 and reactivity with vimentin in not uncommon in the epithelial component. The presence of heterologous components may be confirmed by immunohistochemistry including desmin, myogenin, and myoD1 for rhabdomyosarcoma or S-100 for chondrosarcoma. Reactivity with chromogranin, neural specific enolase, and synaptophysin is found in one-sixth of the cases.

Histogenesis

MMMTs are of epithelial cell origin and molecular studies favor a monoclonal origin by showing concordant TP53 abnormalities within the carcinoma and sarcoma component.76,77,80 Further indirect evidence supporting the epithelial origin is that MMMTs may present as recurrence of high-grade serous carcinomas,81 and that the metastatic pattern of MMMTs is also similar to that of high-grade serous carcinomas.

Somatic Genetics

MMMTs are probably monoclonal as the histologically different components share similar allelic losses and retentions.76–78 A cell line developed from an MMMT has expressed both epithelial and mesenchymal antigens.82 Tumor progression (clonal evolution) could explain the heterogeneous pattern of LOH in either the carcinoma or sarcoma components of the neoplasm.77

Differential Diagnosis

1. MMMT versus immature teratoma. Immature teratoma occurs predominantly in children and adolescents and typically contains elements derived from all three germ layers. Neuroectodermal tissue, which is rarely found in MMMT, is almost always the predominant malignant component. In addition, the malignant epithelial component of immature teratoma has an embryonal appearance and the cartilaginous component resembles fetal cartilage with uniform nuclei, in contrast to the cartilage found in MMMT in which the cells are bizarre and appear clearly malignant (chondrosarcoma) (see Chapter 29).

2. MMMT versus poorly differentiated Sertoli–Leydig cell tumor with heterologous elements. The latter tumor nearly always occurs in young women, many of whom present because of virilization. Usually, some area is better differentiated and readily diagnosable as Sertoli–Leydig tumors. Reactivity for α-inhibin and calretinin (Sertoli–Leydig) and EMA (in MMMT) also facilitates the diagnosis (see Chapter 28).

3. MMMT versus endometrioid stromal sarcomas with sex cord-like differentiation. The latter tumors are better differentiated than MMMTs and often exhibit sex cord differentiation (see later).

4. MMMT versus sarcoma-like mural nodules in mucinous cystic tumor. The mural nodules may be reactive, composed of anaplastic carcinoma, or truly sarcomatous (see Chapter 26).

Tumor Spread and Prognosis

Over 75% of MMMTs have spread beyond the ovary at the time of diagnosis, 60% being stage III and 10% stage IV.1 The metastases commonly contain both carcinomatous and sarcomatous components. The prognosis is very poor. After cytoreductive surgery and platinum-based chemotherapy, the overall 5 year survival is under 30%. Only 25% of patients survive 2 years (median survival, 10 months).1

Müllerian Adenosarcomas

Ovarian adenosarcomas are usually unilateral and predominantly solid tumors containing numerous small cysts. Over 50 cases have been reported.83,84 They occur in older women (mean age, 54 years) and have a much worse prognosis than their more common uterine counterparts; 50% die within 5 years.

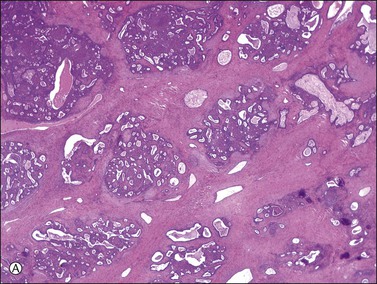

Microscopically, the tumors exhibit both a malignant stromal and a glandular component. The glandular epithelium, which is usually of endometrioid type (Figure 27.26), appears benign or less frequently atypical. The stroma resembles a cellular fibroma, low-grade fibrosarcoma, or low-grade endometrial stromal sarcoma. Typically, it is most cellular adjacent to the glands forming cuffs around them (‘periglandular cuffing’). The glands become cystic and polypoid projections of stroma into the lumens (phyllodes-like pattern) are often present. Mitoses in the stromal cells range from 2 to <40 per 10 HPF.83 Heterologous elements, sex cord-like structures, and sarcomatous overgrowth are occasionally found.

< div class='tao-gold-member'>

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree