Patient Story

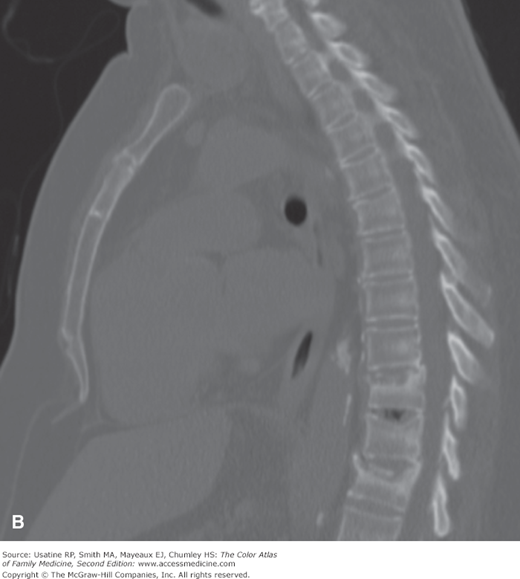

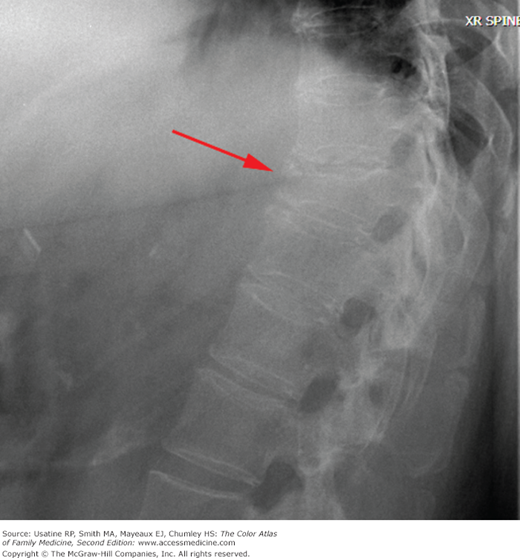

An 83-year-old woman accompanied by her 56-year-old daughter presents to the office with severe upper back pain over the past 2 days. Her medical problems include hypothyroidism, for which she is on replacement medication, and mild hypertension, which is controlled with a diuretic. She has known osteopenia and was taking calcium and vitamin D but had not tolerated a bisphosphonate. Physical examination reveals moderate thoracic kyphosis and tenderness over several lower thoracic vertebrae. A plain radiograph demonstrates a vertebral compression fractures (Figure 225-1A). The daughter asks about management options for pain and prevention of future fractures and also about screening for herself. As there was a suggestion of multiple compression fractures a CT was ordered to better visualize the fractures (Figure 225-1B).

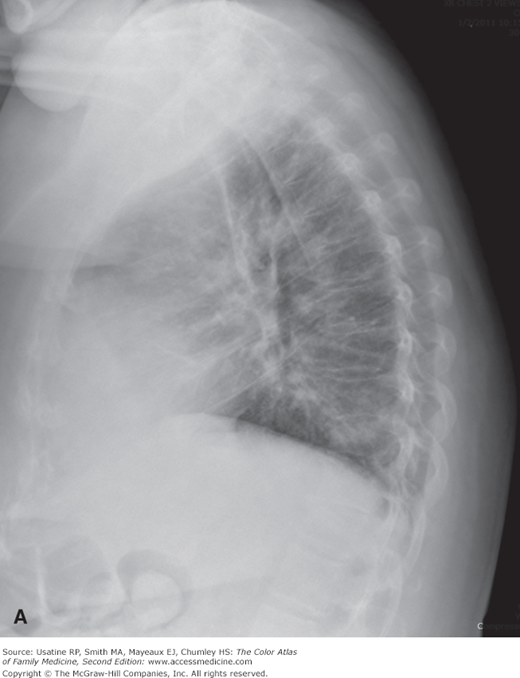

Figure 225-1

Osteoporosis-related thoracic vertebral compression fractures in an 83-year-old woman with kyphosis. A. Lower thoracic vertebral compression fractures seen on the lateral plain radiograph. B. Same fractures visualized more clearly on a lateral CT of the spine. (Courtesy of Rebecca Loredo-Hernandez, MD.)

Introduction

- Osteoporosis is a skeletal disorder characterized by low bone mineral density (BMD) ≤2.5 standard deviations (SD) of the mean for a gender-matched young white adult and compromised bone strength predisposing a person to fracture from minimal trauma.

- Osteopenia is defined as a BMD measurement of between 1.0 and 2.5 SD below the gender-matched young white adult mean. The World Health Organization also defines osteoporosis as a history of fragility fractures and osteopenia.1

Epidemiology

- Approximately 12 million Americans older than age 50 years are have osteopenia.2

- Half of all postmenopausal women will have an osteoporosis-related fracture in their lifetime; 25% will experience a vertebral deformity and 15% will suffer a hip fracture.2

- Low BMD at the femoral neck (T-score of −2.5 or below) is found in 21% of postmenopausal white women,16% of postmenopausal Mexican American women, and 10% of postmenopausal African American women.3

- About 1 in 5 older men are at risk of an osteoporosis-related fracture.2

- Vertebral fractures can cause severe pain and lead to 150,000 hospital admissions per year in the United States.

- Following a hip fracture, more than 30% of men and approximately 17% of women die within 1 year and more than half are unable to return to independent living.3

Etiology and Pathophysiology

- Primary osteoporosis is either a result of aging changes or menopause.

- Usually affects those older than age 70 years.

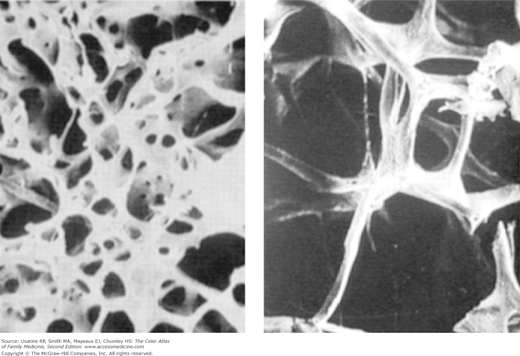

- Proportionate loss of cortical and trabecular bone density (Figure 225-2). Bone mass peaks at approximately age 30 years and declines thereafter. This bone loss can lead to an increase in vertebral, hip, and radius fractures.

- In the 15 years following menopause, there is a disproportionate loss of trabecular bone. This can lead to an increase in fractures of the vertebrae, distal forearm, and ankle.

- Usually affects those older than age 70 years.

- Secondary osteoporosis is a result of medical conditions or medications (Table 225-1). Long-term oral prednisone used to treat a number of autoimmune diseases is a major contributing cause of secondary osteoporosis (Figure 225-3).

Figure 225-2

Normal trabecular bone (left) compared with trabecular bone murmur patient with osteoporosis (right). The loss of mass in osteoporosis these bones more susceptible to breakage. (Printed with permission from Barrett KE, Barman SM, Boitano S, et al. Ganong’s Review of Medical Physiology, 23rd ed. Philadelphia, McGraw-Hill Medical; 2009.)

Genetic factors

| Medications (commonly used)

|

Nutritional factors

| Lifestyle factors

|

Medical disorders

| |

Risk Factors

- See Table 225-1.

- Previous low-trauma fracture.4 Other risk factors for an osteoporosis-related fracture include advanced age, low BMD, low body mass index (BMI), and starred items in Table 225-1.3

- There are many validated clinical decision rules that can help identify patients who are at higher-than-average risk of fracture.5,6 An extensively validated online tool developed by the World Health Organization, the Fracture Risk Assessment (FRAX) (http://www.shef.ac.uk/FRAX/), can be used to estimate 10-year risk for fractures for women and men based on easily obtainable clinical information, such as age, BMI, parental fracture history, and tobacco and alcohol use.

Diagnosis

- Height loss (>1 cm or >0.8 inch) can alert the clinician to osteoporosis.

- Kyphosis and cervical lordosis (dowager’s hump).

- Acute pain is often the first symptom from a fracture, usually of the vertebrae (vertebral body collapse), hip or forearm, especially occurring after minor trauma. Pain may also be elicited from palpation over spinous processes and paraspinous muscle spasm may be noted.

- Osteoporosis may be identified on x-ray done for another purpose.

- Fractures caused by menopausal osteoporosis typically occur in thoracic vertebrae, distal forearm, and ankle; occasionally there is loss of teeth.

- Fractures caused by senile osteoporosis are in the vertebrae, hip, and radius.