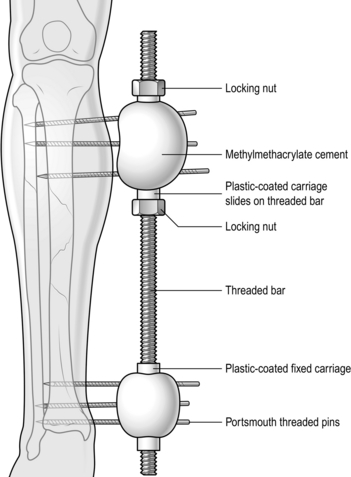

30 1. Most elective orthopaedic operations are carried out on otherwise healthy patients, but always assess the patient’s fitness for operation beforehand. When operating for trauma, ensure that the patient is adequately resuscitated. 2. Postpone elective operations until any concomitant illness such as a chest or urinary infection or hypertension has been corrected. This is especially so if one is contemplating implanting a prosthetic device (e.g. a total joint replacement). 3. Correct blood loss and dehydration before emergency operations. 4. Antibiotics. It is recommended practice usually to administer an antibiotic intravenously at the time of induction of anaesthesia, followed up by two further doses at 8-hourly intervals, making three doses in all. The choice of antibiotic depends upon the nature of the operation, the likely infecting organism and the patient’s potential sensitivity. It is usual to use a broad-spectrum antibiotic (e.g. cefradine 500 mg t.d.s.) or an agent that has a potent anti-staphylococcal activity. 5. Anticoagulation. The routine use of prophylactic anticoagulants for major orthopaedic operations, particularly on the hip joint, is controversial. The current consensus from the British Orthopaedic Association1 is that, while chemical agents (e.g. heparin and warfarin) may reduce the incidence of deep venous thrombosis, death from other causes may be increased and there is no reduction in the rate of fatal pulmonary embolism. Anticoagulant therapy itself may also lead to excessive intra- or postoperative bleeding complications and ultimately jeopardize a total joint replacement. However, where there is a previous history of thromboembolic disease it is advisable to give heparin 5000 IU subcutaneously twice daily. If the patient is already fully anticoagulated, aim to reduce the international normalized ratio (INR) to <2 over the perioperative period, maintaining the patient on intravenous heparin infusion and reverting to oral anticoagulation when the patient is mobile – hopefully within 24–48 hours. 6. Anaesthesia. General anaesthetic is appropriate for most orthopaedic procedures, especially for prolonged operations when a tourniquet is used. Under some circumstances (e.g. a patient with rheumatoid arthritis), it may be preferable to operate under a regional block (spinal, epidural, axillary). Some procedures (e.g. carpal tunnel decompression) may be performed using a local anaesthetic wound infiltration. In addition, local anaesthetic is a useful adjunct in postoperative pain relief. In our opinion Bier’s block, while theoretically safe, provides an unsatisfactory operative field for anything but the simplest of procedures. 1. Apply a pneumatic tourniquet of appropriate size over a few turns of orthopaedic wool around the proximal part of the upper arm or thigh. 2. Exsanguinate the limb either by elevation (Bier’s method) or with a soft rubber exsanguinator (Rhys-Davies). If the latter is not available, use an Esmarch bandage, but take particular care if the skin is friable, as in a patient with rheumatoid disease. A stockinette applied over the skin prior to exsanguination reduces the likelihood of shear stresses and potential skin damage. 3. Secure the cuff and inflate until the pressure just exceeds the systolic blood pressure for tourniquets on the upper limb, and to twice the systolic blood pressure for tourniquets on the lower limb. In practice, 200 mmHg is appropriate for the upper limb and 350 mmHg for the leg. Higher pressures are unnecessary and may cause soft-tissue damage by direct compression, especially in thin patients. Never allow the pressure to exceed 250 mmHg in the arm or 450 mmHg in the leg. 4. If the tourniquet is accidentally deflated or slips during the operation, allowing partial or complete return of the circulation, deflate the cuff completely, re-position and re-fasten it and elevate the limb before re-inflating the cuff. 5. We prefer to release the tourniquet and achieve satisfactory haemostasis before closing the wound. Some surgeons, however, prefer to close and dress the wound prior to tourniquet release. Under these circumstances a drain is usually necessary and any plaster must be split. 1. On completion of the operation always ensure that the circulation has returned to the limb. Locate and mark the position of the peripheral pulses to facilitate subsequent postoperative observations. 2. Reduce the likelihood of swelling by applying bulky cotton wool and crepe bandage dressing for at least 24 hours after the operation. Encourage and supervise active exercises. A good orthopaedic maxim is ‘Don’t just lie there – do something!’ 1. There should be no break or superficial infection in the skin of a limb or the area of the trunk that is to be operated on. If necessary, postpone the operation until any wound has healed or infection has been eradicated. 2. Instruct the patient to bathe or shower within 12 hours of the operation using an antiseptic soap. Preoperative shaving is a matter of personal preference, but should be performed as late as possible and by an expert. Poor preoperative shaving may result in multiple skin nicks, which in turn become colonized with bacteria, increasing the risk of postoperative infection. 3. Mark the limb or digit to be operated on with an indelible marker. Give instructions to re-mark it if the mark is accidentally erased before the operation. 4. Prepare the skin with either iodine or chlorhexidine in spirit or aqueous solution. Iodine solutions are more effective skin antiseptics but are also the most irritant. Avoid pooling of alcohol-based solutions beneath a tourniquet or diathermy pad, with an attendant risk of explosion. 1. Prepare the skin in the anaesthetic room after induction of anaesthesia. 2. Cover open wounds with a sterile dressing held in place by an assistant. 3. Clean the surrounding skin with a soft nail brush and warm cetrimide (Savlon) solution, removing ingrained dirt and debris. 4. Remove the dressing and clean the wound itself in similar fashion to remove all dirt and debris, controlling bleeding by local digital pressure. 5. Irrigate the wound with copious volumes of physiological saline. A pulsed lavage system may be extremely helpful in this regard. 6. Complete the cleansing and irrigation of the wound in the theatre as part of the definitive surgical treatment. 1. Resuscitate the patient, if necessary, according to ATLS (advanced trauma life support) principles and guidelines before dealing with an open wound. 2. Take a culture swab from the wound and send it for culture and sensitivities. This may be useful in the management of later infection. 3. If possible take a Polaroid or digital photograph of the wound prior to the dressing being applied, to give you (or the treating surgeons) an idea of the extent and configuration of the underlying wound and to avoid disturbing the dressings unnecessarily. 4. Stop the bleeding by applying local pressure. Elevate the limb if necessary. Do not attempt blind clamping of any bleeding vessels, to avoid damaging adjacent structures. 1. Determine how the wound was sustained and whether it is recent and clean or long-standing and dirty, and if it is superficial or deep. The longer the period since the injury and the deeper and dirtier the wound, the greater the need for antibiotics and tetanus prophylaxis. 2. Consider what structures may have been damaged and test for the integrity of arteries, nerves, tendons and bones. 3. Make an initial assessment of skin loss or damage and look for exit wounds following penetrating injuries. 4. An X-ray will show the extent of bone damage and the presence of radio-opaque foreign bodies (remember that not all foreign bodies are radio-opaque). 5. Always request X-rays of the skull, lateral cervical spine, chest and anteroposterior views of the pelvis in multiply injured patients, but do not let this delay treatment. 6. Depending on the extent of the wound, carry out further assessment and treatment without anaesthesia or with regional or general anaesthetic. Avoid local infiltration anaesthesia. 1. Give a broad-spectrum antibiotic, unless the wound is clean, superficial and recent in origin. 2. If the wound is dirty, deep and more than 6 hours old, give 1 g of benzylpenicillin, and 0.5 ml of tetanus toxoid intramuscularly if the patient has been actively immunized in the past 10 years. 3. If the patient has not been actively immunized, give 1 vial (250 units) of human tetanus immunoglobulin in addition to the toxoid. Ensure that further toxoid is given 6 weeks and 6 months later. 4. Clean the wound and prepare the skin, as described above. 1. Gently explore the wound, examining the skin, subcutaneous tissues and deeper structures. Follow the track of a penetrating wound with a finger or a probe to determine its direction and to judge the possibility of damage to vessels, nerves, tendons, bone and muscle. If you suspect muscle damage, slit open the investing fascia and take swabs for an anaerobic bacterial culture. Decide into which category the wound falls, since this determines the subsequent management. 2. Simple clean wounds have no tissue loss, although all wounds are contaminated with microorganisms, which may already be dividing. In clean wounds seen within 8 hours of injury, the bacteria will not yet have invaded the tissues. 3. Simple contaminated wounds have no tissue loss. However, they may be heavily contaminated and if you see them more than 8 hours after the injury, they can be assumed to be infected. Late wounds show signs of bacterial invasion, with pus and slough covering the raw surfaces, and redness and swelling of the surrounding skin. Although there is no loss of tissue from the injury, the infection will result in later soft-tissue destruction. 4. Complicated contaminated wounds result when tissue destruction (e.g. loss of skin, muscle or damage to blood vessels, nerves or bone) has occurred, or foreign bodies are present in the wound. Recently acquired low-velocity missile wounds fall into this category since there is insufficient kinetic energy to carry particles of clothing and dirt into the wound. 5. Complicated dirty wounds are seen after heavy contamination in the presence of tissue destruction or implantation of foreign material, especially if the wound is not seen until more than 12 hours have elapsed. 6. High-velocity missile wounds deserve to be placed in a category of their own. For instance, when a bullet from a high-powered rifle strikes the body it is likely to lose its high kinetic energy to the soft tissues as it passes through, resulting in extensive cavitation. Although the entry and exit wounds may be small, structures within the wound are often severely damaged. Muscle is particularly susceptible to the passage of high-velocity missiles and becomes devitalized. It takes on a ‘mushy’ appearance and consistency and fails to contract when pinched or to bleed when cut. If the bullet breaks into fragments or hits bone, breaking it into fragments, the spreading particles of bullet and bone also behave as high-energy particles. The whole effect is of an internal explosion. In addition, the high-velocity missile carries foreign material (bacteria and clothing) deeply into the tissues, causing heavy contamination. 7. Open fractures can be classified in a variety of ways. Probably the most widely accepted is the Gustilo classification, which is particularly useful in discussing soft-tissue reconstruction: 1. Stop all bleeding. Pick up small vessels with fine artery forceps and cauterize or ligate them with fine absorbable sutures. Control damage of major arteries and veins with pressure, tapes or non-crushing clamps, so as to permit later repair. 2. Irrigate clean simple wounds with copious volumes of sterile saline solution without drainage. Do not attempt to repair cleanly divided muscle with stitches but simply suture the investing fascia. Close the skin accurately. 3. Complicated contaminated wounds can be partially repaired after excising the devitalized tissue. Once bone stability has been achieved, damaged segments of major arteries and veins should be repaired by an experienced surgeon, using grafts where appropriate. Loosely appose the ends of divided nerves with one or two stitches in the perineurium, so that they can be readily identified and repaired later when the wound is healed and all signs of inflammation have disappeared. Similarly, identify and appose the ends of divided tendons in preparation for definitive repair at a later date. Do not remove small fragments of bone that retain a periosteal attachment or large fragments whether they are attached or unattached. Excise devitalized muscle, especially the major muscle masses of the thigh and buttock. Remove foreign material when possible. Some penetrating low-velocity missiles are better left if they lie deeply, provided damage to important structures has been excluded. Remove superficial shotgun pellets. Low-velocity missile tracks do not normally require to be laid open or excised, but do not close the wound. Excise damaged skin when the deep flap can be easily closed, if necessary by making a relaxing incision or applying a skin graft. Do not lightly excise specialized skin from the hands; instead leave doubtful skin and excise it later, if necessary, on expert advice. 4. Stabilize any associated fracture. It may be possible merely to immobilize the limb in a plaster cast, cutting a window into it so that the wound can be dressed. An open fracture, however, is not an absolute contraindication to surgical stabilization using the appropriate device (plates and screws, intramedullary nails), but such should be undertaken only by an experienced trauma or orthopaedic surgeon. In an emergency situation it is preferable to use temporary skeletal traction and external fixator. 5. Complicated dirty wounds require similar treatment of damaged tissues such as nerves and tendons, but do not attempt to repair damaged structures other than major blood vessels. Pack the wound and change the dressing daily until there is no sign of infection, then close the skin by suture or by skin grafting. 6. Lay open high-velocity missile wounds extensively. Foreign matter, including missile fragments, dirt and clothing, is carried deeply into the wound, so contamination is inevitable. Explore and excise the track, since the tissue along the track is devitalized, lay open the investing fascia over disrupted muscle to evacuate the muscle haematoma and excise the pulped muscle, leaving healthy contractile muscle that bleeds when cut. This leaves a cavity in the track of the missile. 7. Mark divided nerves and tendons for definitive treatment later. Excise the skin edges and pack the wound with saline-soaked gauze. Treat any associated fracture as described above. Change the packs daily until infection is controlled and all dead tissue has been excised. Only then can skin closure be completed and the repair of damaged structures be planned. The Ilizarov and similar circular frames are beyond the scope of this chapter, but in an emergency you should be familiar with the principles involved, and the techniques of applying a simple unilateral frame. Such a frame is constructed from one or more rigid bars which are aligned parallel to the limb and to which the threaded pins that are drilled into the fragments of bone are attached. In the more sophisticated devices (Orthofix, AO, Monotube, Hoffman) this is done by clamping the pins to universal joints, which allow the position of the fragments to be adjusted before the clamps are finally tightened. In the simplest form, here described, the pins are held to the bar with acrylic cement (Denham type; Fig. 30.1). 1. Make a stab wound through healthy skin proximal to the fracture site, bearing in mind the possible need for subsequent skin flaps. 2. Drill a hole through both cortices of the bone, approximately at right-angles to the bone, with a sharp 3.6-mm drill. Take care in drilling the bone that the drill bit does not overheat, which may in turn cause local bone necrosis leading to the formation of ring sequestra with subsequent loosening and infection of the pins. Measure the depth of the distal cortex from the skin surface. 3. Insert a threaded Schantz pin into the drill hole so that both cortices are penetrated. 4. If possible, insert two more pins approximately 3–4 cm apart into the proximal fragment and three pins into the distal fragment in similar fashion. Biomechanically, the stability of the fixator is enhanced if there are three pins in each of the major fragments, with the nearest pin being close to the fracture line. 5. Loosen the locking nuts that hold the carriages on to the rigid bar and hold the bar parallel to the limb and 4–5 cm away from the skin. 6. Place one carriage opposite the protruding ends of each set of three pins and adjust the locking nuts to hold the carriages in position. 7. Fix the pins to the carriages with two mixes of acrylic cement for each carriage, moulding the cement around the pins and the carriage, maintaining the position until it is set. 8. Remove any temporary reduction device and carry out the final adjustment on the locking nuts to compress the bone ends together.

Orthopaedics and trauma

general principles

PREOPERATIVE PREPARATION

Appraise

TOURNIQUETS

Appraise

Most orthopaedic operations on the limbs, especially the hand, are facilitated if performed in a bloodless field using a pneumatic tourniquet. It has been said that attempting to operate on a hand without a tourniquet is akin to trying to repair a watch at the bottom of an inkwell!

Most orthopaedic operations on the limbs, especially the hand, are facilitated if performed in a bloodless field using a pneumatic tourniquet. It has been said that attempting to operate on a hand without a tourniquet is akin to trying to repair a watch at the bottom of an inkwell!

Use a tourniquet with caution if the patient suffers from peripheral vascular disease or if the blood supply to damaged tissues is poor. Peripheral vascular disease, however, is not an absolute contraindication to the use of a tourniquet.

Use a tourniquet with caution if the patient suffers from peripheral vascular disease or if the blood supply to damaged tissues is poor. Peripheral vascular disease, however, is not an absolute contraindication to the use of a tourniquet.

Action

Aftercare

SKIN PREPARATION

Elective surgery

Emergency surgery

OPEN WOUNDS

Appraise

Prepare

Assess

Type I: an open fracture with a cutaneous wound <1 cm.

Type I: an open fracture with a cutaneous wound <1 cm.

Type II: an open fracture with extensive soft-tissue damage.

Type II: an open fracture with extensive soft-tissue damage.

Type IIIA: high-energy trauma irrespective of the size of the wound. There is adequate soft-tissue coverage of the fractured bone, despite extensive soft-tissue lacerations or flaps.

Type IIIA: high-energy trauma irrespective of the size of the wound. There is adequate soft-tissue coverage of the fractured bone, despite extensive soft-tissue lacerations or flaps.

Type IIIB: there is an extensive soft-tissue injury with loss of tissue, accompanied by periosteal stripping and bone exposure. These wounds are usually associated with massive contamination.

Type IIIB: there is an extensive soft-tissue injury with loss of tissue, accompanied by periosteal stripping and bone exposure. These wounds are usually associated with massive contamination.

Type IIIC are open fractures associated with vascular and/or neurological injury requiring repair.

Type IIIC are open fractures associated with vascular and/or neurological injury requiring repair.

Action

EXTERNAL FIXATION

Action

![]()

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

Orthopaedics and trauma: general principles