Organization at the Corporate Level

A staff of four hundred represents the critical number in a firm taken over. It is the number which separates the personal boss from the high-level manager. A man (person) may run a firm of four hundred or fewer people extremely well, but that is the maximum he can run personally, knowing all their names, without too much delegated authority. If you expand that firm to, say, 1,100, you may destroy him: Instead of all being people he knows by name, they become pegs on a board; instead of just doing and deciding he has to do a lot of explaining and educating, instead of checking up on everything himself, he has to institute a system and establish procedures. All this demands skills quite different from those he built his success on, and ones which he may well lack.

–Antony Jay. From Management and Machiavelli.

VIEWING AN OVERALL CORPORATE ORGANIZATION

Various Perspectives on Viewing a Company’s Structure

Before discussing models that are frequently used to organize a pharmaceutical company, it is important to identify how a company is viewed by managers who must operate the organization. Two basic ways of viewing a company are in terms of (a) current organizational structures and reporting relationships that have grown up over the years or (b) activities that are carried out by groups that make up the company. The former view takes cognizance of the contradictions and conflicts plus other warts and blemishes in the way a company is structured and operates. Titles and even arbitrarily imposed reporting relationships are viewed as relevant and important. The other viewpoint is functionally oriented and sees a company in terms of flow charts of how things get accomplished. Relevant groups are considered in terms of their activities, procedures, and interactions. According to this functional view, a company should be organized to facilitate these activities and relationships.

A company may also be viewed as an allocation of resources from senior managers to more junior managers and then to even

more junior managers and, finally, to the staff who use those resources. Resources are primarily staff and money but also include information and other categories (see Chapter 3). Each level in a company has different needs and wants in terms of resources required to fulfill their function. When an organization is structured to facilitate communications among and between its employees and managers, it is better able to allocate its resources.

more junior managers and, finally, to the staff who use those resources. Resources are primarily staff and money but also include information and other categories (see Chapter 3). Each level in a company has different needs and wants in terms of resources required to fulfill their function. When an organization is structured to facilitate communications among and between its employees and managers, it is better able to allocate its resources.

Finally, a company may also be viewed from the perspective of an employee or executive in terms of one’s own discipline and department. This view stresses the relationship between one’s area and the overall organization in terms of structure and function. On this more personal level, employees may perceive benefits and drawbacks of their positions relative to the way that the company is organized. They may also assess the structure insofar as it facilitates or hinders various work activities and facilitates or hinders progress in drug development. Other criteria used from an insider’s personal perspective may be expressed in terms of company culture, image, traditions, personnel, political issues, and the way in which work actually is accomplished.

These different views present a challenge. How can a single organizational structure and set of operating procedures be established to fit all of the dissimilar and conflicting aspects of the perspectives described while maintaining balance and cooperation in developing drugs and running a company?

Issues to Address in Deciding How to Organize a Company or Subunit

The two most important issues to focus on in deciding how to organize a company (or another group) in the pharmaceutical industry are (a) personnel—specific individuals present who will be involved (or could be involved) in the organization and (b) functions that must be accomplished through the organization. Either of these considerations (or a blend of both) could be the major influence on the particular organizational structure that is established.

A company may be people oriented and want to use that factor as the basis for their organizational structure, but the company may not have a sufficient number of suitable staff around whom to structure their company, division, or department. In that situation, the most senior position should be filled first, and that individual would then help recruit and hire the rest of the staff. For example, Glaxo Inc. hired Dr. Pedro Cuatrecasas to establish an initial research group in the United States. He then began to hire senior managers, and the research organization rapidly took shape. If a company believes that structure itself is more important to define than to identify the people who will fill each slot, then relevant individuals may proceed to organize their company on paper. The most appropriate people to fill each position (either from within the company or as new hires) are considered and chosen after the agreed-upon organizational structure is in place. One of the justifications for this latter approach is that people come and go, but it is generally believed that a company’s structure should have a greater permanence. This is especially true for larger companies.

When building an organization based on function, it is especially important that the logic underlying the new structure make sense to employees. The logic used should mimic present routes of work that are efficient whenever it is realistic to do so. If work patterns and procedures are to change because of a new or modified structure, a great deal of education may be needed to convince people that the new organizational structure will improve efficiency.

Building a large organizational structure solely around people or around work functions is generally inappropriate. An organizational structure based on an ideal or theoretical set of functions is sterile because it does not consider specific people present in the company who will be asked to fill most, if not all, positions. Building a structure solely around people may lead to serious problems when an important person leaves the company or even changes positions within the company. This is a dilemma that is faced by many companies, and there is no easy answer except to aim for a system that best fits the company and considers these and other issues.

When a company’s organizational structure is to be modified, it is important that the changes made are in concert with other parts of the organization that are intended to remain stable. It is clearly necessary to plan carefully the integration of established and newly modified (or added) areas.

MODELS OF A COMPANY’S OVERALL ORGANIZATION

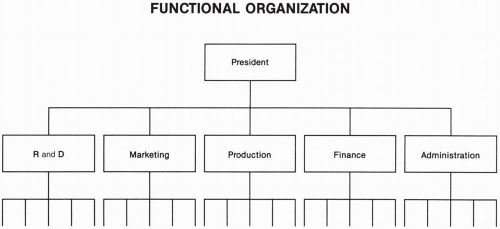

It is said by some theoretical business school academicians that all businesses are organized according to one of three basic models. These models are to organize (a) by function, (b) by division or product (profit center), or (c) using a matrix approach. These three models are illustrated in Figs. 19.1, 19.2, 19.3.

Functional Model

The functional model (Fig. 19.1) is the structure present in most pharmaceutical companies. The departments in each function report to a central person (e.g., department head), who governs the group’s activities. The major advantage of organizing a company according to the functional model is that individuals deal most often with people who have similar backgrounds and training. The major disadvantages are that there tends to be little communication with groups in other functional areas, and fewer people have an overall or broad corporate view.

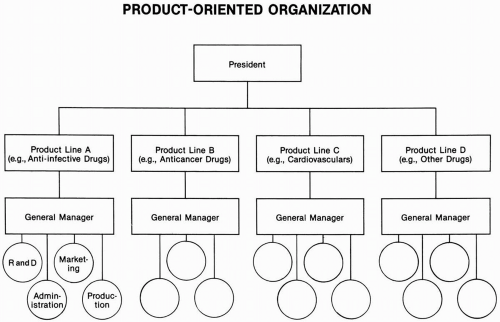

Product-oriented Model

Figure 19.2 illustrates a product-oriented (i.e., division-oriented) organization. The prototype company that used the divisional approach is General Motors. Each car division was at one time organized like a stand-alone business and had its own marketing, research and development (R and D), and other functions. Some pharmaceutical companies have organized themselves around self-contained business units such as consumer products, diagnostics, hospital supplies, and ethical drugs. In theory, at least, each of these business units could be almost totally independent. A major advantage of this approach is to encourage the General Manager of each division to be as successful as possible. The major disadvantage is a duplication of many functions that otherwise would be centralized. One variation on this theme is for only one of the functions in Fig. 19.1 to organize itself using this model.

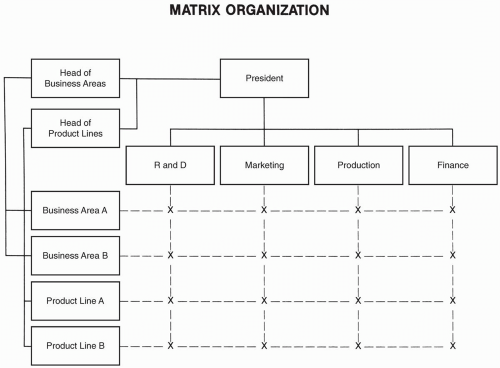

Matrix Model

Figure 19.3 illustrates a matrix structure. The matrix approach recognizes the importance of both functional and product-oriented models. None of the business managers control the resources they

need but must negotiate with line managers to get resources. Therefore, businesses may compete among themselves for resources. Separate teams are established to run each business. This model has advantages over the divisional model in Fig. 19.2 because there is less duplication, waste, and inefficiency. Resources are shared between businesses in the matrix model. The matrix model recognizes business interdependence and, in theory, offers greater flexibility than the other models.

need but must negotiate with line managers to get resources. Therefore, businesses may compete among themselves for resources. Separate teams are established to run each business. This model has advantages over the divisional model in Fig. 19.2 because there is less duplication, waste, and inefficiency. Resources are shared between businesses in the matrix model. The matrix model recognizes business interdependence and, in theory, offers greater flexibility than the other models.

Advantages of a matrix organization are that it is client oriented, promotes teamwork, minimizes intergroup conflict, is more responsive to change, provides greater visibility for lower level employees, and offers multiple career paths. Major disadvantages of a matrix organization are that it (a) dilutes authority of line function managers, (b) requires greater interpersonal skills on the part of numerous managers to succeed, (c) requires cooperation of line function managers, and (d) leads to a greater erosion of detailed technical skills.

An organization’s matrix should not solely be viewed in two dimensions as shown in Figs. 19.3, 19.4, 19.5. It is really necessary to think along three axes. The major axes for a multinational pharmaceutical company are (a) business areas, (b) function or discipline, and (c) geographical location. A particular company may be balanced or dominated by one or more of these dimensions. For example, the over-the-counter (OTC) business may be dominant (dimension one), the marketing function may be dominant (dimension two), or the US operation may be dominant (dimension three).

Although the model in Fig. 19.3 illustrates integration of an entire company, it is possible for one group of a functional model (Fig. 19.1) to use some methods of this matrix model; however, the head of the functional group who uses a matrix cannot give as much autonomy to a matrix group as in the pure matrix model shown in Fig. 19.3, where all functional groups are involved. In the matrix model, it is possible to organize a company around types or groups of products (e.g., diagnostics, OTCs) or customers (e.g., hospitals, health maintenance organizations, private doctors).

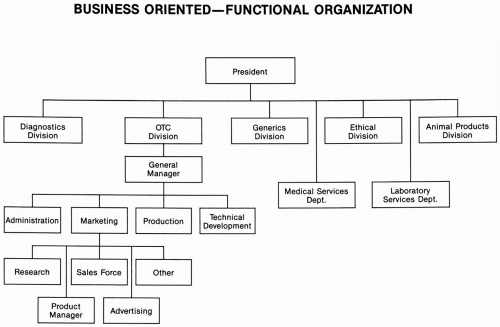

Other Models

In addition to the traditional models shown in Figs. 19.1, 19.2, 19.3, there are numerous hybrid-type organizations that are possible (e.g., Figs. 19.4 and 19.5).

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree