Figure 44-1 Rapid evaluation of ophthalmologic problems.

OCULAR HISTORY AND PHYSICAL EXAM

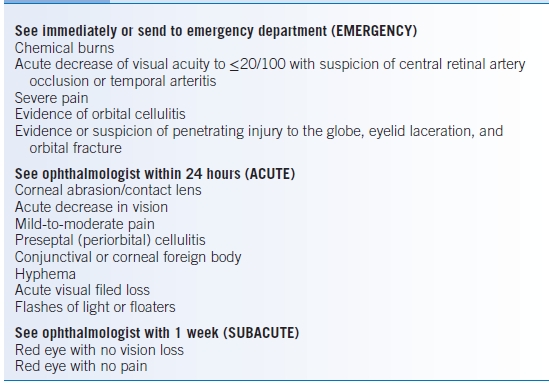

Careful history and examination are essential for correct diagnosis, triage (Table 44-1), and treatment of ocular conditions.

TABLE 44-1 Ophthalmology Referral Guide

History

- Correct diagnosis depends on a carefully taken, complete medical history, including past medical history, medications, family history, social history, and occupational history.

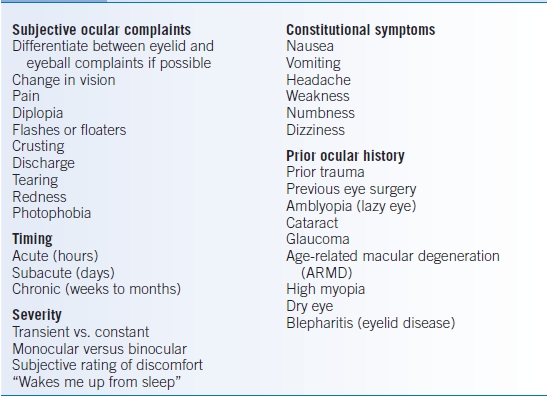

- Key elements of the ocular history are presented in Table 44-2.

- An essential initial step is to determine whether symptoms presented acutely, subacutely, or chronically.

TABLE 44-2 Elements of the Ophthalmologic History

Physical Examination

- Visual acuity

- Obtaining an accurate, best-corrected visual acuity is the most important component of the physical exam.

- Visual acuity should be tested in each eye while the patient is wearing glasses. Ideally a distance chart should be used; however, a near card can yield useful information as well.

- If formal vision charts are not available, have the patient attempt to read newspaper print or your name badge.

- If the patient cannot read the largest font on the chart, halve the distance between the patient and the chart and document the vision with “10” in the numerator (e.g., 10/200). If the patient still cannot read the chart check their ability to count fingers, or perceive hand motion or light.

- If patients do not have their glasses with them, their visual acuity when looking through a pinhole can be checked. Pinholing may resolve refractive error and is useful in the patient who cannot be optimally corrected.

- Obtaining an accurate, best-corrected visual acuity is the most important component of the physical exam.

- Pupillary exam

- Compare the size and shape of the pupils in light and dark conditions.

- Check for an afferent pupillary defect (APD) using the swinging flashlight test. When a light is directed from one eye to the other while the patient focuses on a distant target, the pupils should remain symmetrically constricted owing to the consensual light response. If the pupils dilate when the light is moved from the right to the left eye, then there is an APD of the left eye.

- Presence of an APD is evidence of optic nerve disease or significant retinal damage and should be evaluated in every patient presenting with vision loss.

- Compare the size and shape of the pupils in light and dark conditions.

- Ocular motility: The alignment of each eye in primary gaze, the ability of each eye to move in all directions of gaze, and the presence of nystagmus should be noted. The location of the corneal light reflex can be used to detect subtle deviations of eye position.

- Visual fields

- Have the patient cover one eye, and, while making eye contact with the patient, hold your fingers out into the four main quadrants.

- Minor field defects can be detected and documented by further visual field testing in the eye professional’s office.

- Have the patient cover one eye, and, while making eye contact with the patient, hold your fingers out into the four main quadrants.

- Intraocular pressure

- Intraocular pressure (IOP) is quantitatively measured in the eye professional’s office by tonometry.

- Extremely elevated IOPs, as occurs in angle-closure glaucoma, can occasionally be assessed qualitatively by palpation.

- Intraocular pressure (IOP) is quantitatively measured in the eye professional’s office by tonometry.

- External exam: Although most of the external exam is ideally performed using a slit lamp microscope, a penlight is useful as an initial screening tool.

- Eyelid examination

- Examine for evidence of erythema, edema, trauma, or eyelid lesions.

- Ptosis can be assessed by measuring the distance in millimeters between the corneal light reflex and the margin of the upper eyelid.

- Assess for proptosis (prominent eyes) or enophthalmos (recession of the eyeball into the orbit).

- Basal cell carcinomas affecting the eyelid most commonly develop on the lower eyelid.1

- Examine for evidence of erythema, edema, trauma, or eyelid lesions.

- Anterior segment examination

- The conjunctiva is the clear vascularized tissue overlying the sclera. Injection of the conjunctiva can occur in many conditions including viral and bacterial conjunctivitis.

- The cornea is the transparent, anterior wall of the outer eye. Assess the clarity of the cornea; any opacity should be characterized as diffuse or focal. Central focal opacities are more detrimental to vision than peripheral opacities.

- The anterior chamber is the fluid-filled space in between the cornea and the iris. White blood cells (hypopyon) or blood (hyphema) in the anterior chamber will obstruct the view of the iris.

- Irregularities in the shape of the iris should be noted.

- The lens lies posterior to the iris and can appear yellow or opaque if a cataract is present. Patients who have had previous cataract surgery could have a shimmering, reflective quality to their lens.

- The conjunctiva is the clear vascularized tissue overlying the sclera. Injection of the conjunctiva can occur in many conditions including viral and bacterial conjunctivitis.

- Fundus examination

- Most examinations in the office setting do not require dilation. Dilated fundus examinations are performed to assess retinal vascular health or to rule out findings, such as papilledema or vitreous hemorrhage.

- Pharmacologic dilation is usually performed in adults with phenylephrine hydrochloride 2.5% or tropicamide 1%, or both, and causes decreased accommodation for 4 to 6 hours.

- The patient should not be dilated without the direction of an ophthalmologist in the following circumstances: suggestion of a shallow anterior chamber, patient undergoing neurologic observation, and any question of an APD.

- Most examinations in the office setting do not require dilation. Dilated fundus examinations are performed to assess retinal vascular health or to rule out findings, such as papilledema or vitreous hemorrhage.

OPHTHALMIC SCREENING

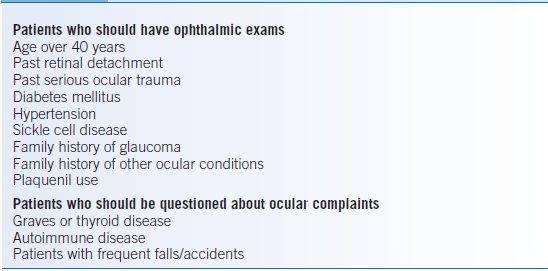

- Patients with specific medical conditions or who are taking certain medications should undergo periodic examinations by an ophthalmologist (Table 44-3).

- Other groups of patients should ideally be specifically asked about ocular complaints (Table 44-3).

- The definition of legal blindness in the U.S. is central visual acuity of 20/200 or less in the better eye with the use of a correcting lens. An eye with a visual field that extends <20 degrees is considered to have a visual acuity of <20/200 regardless of the measured acuity.

- Visual requirements for obtaining a driver’s license are determined by each state.

TABLE 44-3 Indications for Ophthalmic Screening

Symptom-Based Approach

VISION LOSS

Acute vision loss should be evaluated immediately in order to rule out processes that have systemic or devastating sequelae, such as giant cell arteritis, acute angle-closure glaucoma, optic neuritis, endophthalmitis, retinal detachment, and posttraumatic processes (ruptured globe, hyphema).

Acute Painless Vision Loss

Is the process transient or is it present for more than 24 hours?

Transient Vision Loss

- Amaurosis fugax

- Etiology: Amaurosis fugax is transient monocular vision loss due to retinal arterial occlusion. The occlusion is usually caused by a cholesterol or platelet embolus but can result from vasospasm. The most common sources of an atheroma resulting in amaurosis fugax are the carotid arteries. Evidence of a Hollenhorst plaque (refractile cholesterol plaque visible in the retinal vasculature) may be seen on physical examination.

- Symptoms: Often described as a shade or curtain coming over the vision that lasts a few minutes, it is most common in patients >50 years or those with a history of vascular disease. A full ophthalmologic examination must be performed by an ophthalmologist to rule out impending vascular occlusion.

- Management: Medical evaluation, including carotid Dopplers, cardiac echocardiography, and basic hematologic workup, should be performed to rule out systemic disease, even in the absence of Hollenhorst plaques. Patients should be sent to an ophthalmologist immediately if the vision loss has not recovered.

- Etiology: Amaurosis fugax is transient monocular vision loss due to retinal arterial occlusion. The occlusion is usually caused by a cholesterol or platelet embolus but can result from vasospasm. The most common sources of an atheroma resulting in amaurosis fugax are the carotid arteries. Evidence of a Hollenhorst plaque (refractile cholesterol plaque visible in the retinal vasculature) may be seen on physical examination.

- Ophthalmic migraines

- Etiology: A history of migraine may or may not be present. Ophthalmic migraines cause transient episodes that usually lead to at least 5 to 15 minutes of obscuration of vision.

- Symptoms: Fortification (jagged lightning bolts) and scintillating scotomas (blind spot centrally with hazy edges) are characteristic. Colored lights and other visual symptoms can occur. Visual acuity should return to baseline after the episode but headache or mild nausea may follow.

- Management: Careful history should be taken to rule out concomitant neurologic symptoms. Both eyes are usually affected, although it may be sufficiently asymmetric as to appear to be monocular. If truly monocular, then prompt referral to an ophthalmologist is necessary to rule out retinal pathology.

- Etiology: A history of migraine may or may not be present. Ophthalmic migraines cause transient episodes that usually lead to at least 5 to 15 minutes of obscuration of vision.

- Pseudotumor cerebri

- Etiology: Pseudotumor cerebri typically occurs in overweight young women and is more common in pregnancy. It is usually idiopathic but may be caused by vitamin A toxicity (>100,000 U/day), cyclosporine, tetracycline, oral contraceptives, or systemic steroid withdrawal.

- Symptoms: Patients will describe headache, transient visual obscurations often associated with changes in posture, diplopia, tinnitus, dizziness, and nausea.

- Management: If disc edema is seen, then a mass or venous thrombosis should be ruled out by an MRI and MR venography. Elevated opening pressure on lumbar puncture with normal cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) composition will confirm the diagnosis. Send patient to an ophthalmologist who can follow visual fields in order to monitor for vision loss and response to therapy. Counsel the patient on weight loss if overweight. Discontinue any causative medications. Medical treatment is achieved with acetazolamide 250 mg PO qid initially, increasing to 500 mg PO qid if tolerated and necessary. Surgery can be considered if medical options fail however this will require input from an ophthalmologist.

- Etiology: Pseudotumor cerebri typically occurs in overweight young women and is more common in pregnancy. It is usually idiopathic but may be caused by vitamin A toxicity (>100,000 U/day), cyclosporine, tetracycline, oral contraceptives, or systemic steroid withdrawal.

Progressive/Stable Vision Loss

- Giant cell arteritis (GCA) or temporal arteritis (ischemic optic neuropathies)

- Symptoms: This potentially life-threatening disease should always be considered when sudden painless vision loss develops in a patient over 50 years old.2,3 Concomitant symptoms of malaise, weight loss, anorexia, scalp tenderness, jaw claudication, or shoulder/limb girdle weakness should be documented.

- Management: Because this is a systemic disease that may lead to bilateral blindness within a few days, early diagnosis and a high level of suspicion are required. Referral emergently to an ophthalmologist is needed to differentiate between causes of sudden painless vision loss that are associated with GCA versus those that have no association or risk of vision loss in the other eye. If there is a high index of suspicion, consider an immediate dose of oral steroids prior to a patient going for blood work (complete blood count [CBC], erythrocyte sedimentation rate [ESR], C-reactive protein [CRP]) on their way to the ophthalmologist, or presenting to an emergency room. A temporal artery biopsy should be done within 2 weeks of starting steroids in any patient in whom the clinical suspicion is high.

- Symptoms: This potentially life-threatening disease should always be considered when sudden painless vision loss develops in a patient over 50 years old.2,3 Concomitant symptoms of malaise, weight loss, anorexia, scalp tenderness, jaw claudication, or shoulder/limb girdle weakness should be documented.

- Retinal detachment

- Etiology: As the vitreous body pulls away from the retina, it can pull the retina off with it. Patients are at higher risk with increasing age and if they are very near-sighted, postsurgical, or posttrauma. Similar symptoms of acute onset of floaters and occasional flashes but no vision loss may be seen with acute posterior vitreous detachment; however, a dilated exam by an ophthalmologist is still needed to rule out a retinal detachment.

- Symptoms: Presents with constant photopsia (flashing lights), floaters, and sometimes a shade over the part of the vision in one eye. Partial detachments may not affect central visual acuity dramatically, but those that involve the central macular area with significantly decreased visual acuity can be associated with an APD.

- Management: These patients need an emergent extensive dilated retinal examination by an ophthalmologist.

- Etiology: As the vitreous body pulls away from the retina, it can pull the retina off with it. Patients are at higher risk with increasing age and if they are very near-sighted, postsurgical, or posttrauma. Similar symptoms of acute onset of floaters and occasional flashes but no vision loss may be seen with acute posterior vitreous detachment; however, a dilated exam by an ophthalmologist is still needed to rule out a retinal detachment.

- Vascular occlusions: central retinal artery and vein occlusion (CRAO/CRVO) or branch artery and vein occlusions

- Etiology: This is often seen in people with previously diagnosed vascular disease; it may also occur in younger patients and requires evaluation for embolic (for arterial occlusion) or thrombotic (for venous occlusion) disease. On funduscopic examination, there may be evidence of pallor, vascular box-carring, and a cherry-red spot. Optic nerve swelling, venous engorgement, retinal hemorrhage, and cotton-wool spots, are often collectively described as blood and thunder (CRVO).

- Symptoms: Severe painless vision loss generally to the point of counting-fingers vision or worse. Many will awaken with poor vision or describe the very moment at which the vision was affected. As above, patients must be screened for GCA symptoms if over 50 years old.

- Management: Irreversible damage has been shown to occur after 90 minutes of occlusion and, therefore, patients should be sent to the emergency room or for referral immediately.4

- If the patient is diagnosed quickly enough with a CRAO, interventional radiologists may be able to treat the patient with catheterization of the ophthalmic artery and injection with thrombolytics, although this is not commonly indicated.5

- After the acute event, the patient requires a workup for embolic disease and follow-up for late ocular complications including neovascularization and its resultant complications. Follow-up with an ophthalmologist is imperative to treat ocular complications common with these processes.

- If the patient is diagnosed quickly enough with a CRAO, interventional radiologists may be able to treat the patient with catheterization of the ophthalmic artery and injection with thrombolytics, although this is not commonly indicated.5

- Etiology: This is often seen in people with previously diagnosed vascular disease; it may also occur in younger patients and requires evaluation for embolic (for arterial occlusion) or thrombotic (for venous occlusion) disease. On funduscopic examination, there may be evidence of pallor, vascular box-carring, and a cherry-red spot. Optic nerve swelling, venous engorgement, retinal hemorrhage, and cotton-wool spots, are often collectively described as blood and thunder (CRVO).

- Visual field defects

- Etiology: Visual field defects may occur from retinal and optic nerve disease but may also indicate intracranial disease. Lesions anterior to the optic chiasm (e.g., retina, glaucoma, and optic neuritis) produce lesions in one eye only. Pituitary adenomas at the optic chiasm may produce bitemporal field loss. Retrochiasmal (e.g., damage to the optic tracts, radiations, or the occipital cortex) lesions produce homonymous hemianopsias or other homonymous defects. Stroke is the most common cause of homonymous hemianopsia.

- Symptoms: Patients will describe areas in the visual field that are black or missing.

- Management: Generally bilateral visual field loss needs neurologic evaluation and imaging. An ophthalmologist can perform formal visual fields in the office to more precisely determine the pattern of field loss that can help in localization of the pathology.

- Etiology: Visual field defects may occur from retinal and optic nerve disease but may also indicate intracranial disease. Lesions anterior to the optic chiasm (e.g., retina, glaucoma, and optic neuritis) produce lesions in one eye only. Pituitary adenomas at the optic chiasm may produce bitemporal field loss. Retrochiasmal (e.g., damage to the optic tracts, radiations, or the occipital cortex) lesions produce homonymous hemianopsias or other homonymous defects. Stroke is the most common cause of homonymous hemianopsia.

- Vitreous hemorrhage

- Etiology: Vitreous hemorrhage is often seen in those with diabetes, vein occlusions, and retinal holes or breaks. Vitreous hemorrhage may occur after trauma or with any condition that causes abnormal retinal neovascularization. Terson syndrome is vitreous and retinal hemorrhage in association with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).

- Symptoms: Patients will describe sudden onset of floaters, veils, spider webs, or looking through red (blood). Vision can be moderately or severely impaired depending on the amount of bleeding.

- Management: Have the patient maintain an upright posture with the head of bed elevated while sleeping so that the blood may settle. Refer to an ophthalmologist to monitor progression and treat any retinal pathology. Unresolved hemorrhage may eventually require surgical removal. Stopping anticoagulation should only be considered if there is no risk of systemic complications of discontinuing therapy. Discussion with the ophthalmologist regarding the etiology of the bleed may reveal that discontinuing anticoagulation may be of little therapeutic value.

- Etiology: Vitreous hemorrhage is often seen in those with diabetes, vein occlusions, and retinal holes or breaks. Vitreous hemorrhage may occur after trauma or with any condition that causes abnormal retinal neovascularization. Terson syndrome is vitreous and retinal hemorrhage in association with subarachnoid hemorrhage (SAH).

Acute Painful Vision Loss

- Angle-closure glaucoma

- Etiology: Angle-closure glaucoma is a rare disorder that occurs when the anterior chamber is anatomically narrow and the dilated iris closes off the outflow of aqueous humor causing an acute rise in IOP.6 This event can cause an extremely elevated IOP (possibly up to the 70s), and patients are at risk for vascular occlusions and glaucomatous damage to the optic nerve.

- Symptoms: Severe pain, decreased vision, colored halos, corneal edema, and headache/eye pain. Nausea, vomiting, and abdominal pain may also occur. The pupil is usually fixed and does not react to light.

- Management: Send to an ophthalmologist to manage the IOP initially with medications. But the definitive treatment is a laser peripheral iridotomy, which should be performed as soon as possible; this procedure is also done on the unaffected eye for prophylaxis.6

- Etiology: Angle-closure glaucoma is a rare disorder that occurs when the anterior chamber is anatomically narrow and the dilated iris closes off the outflow of aqueous humor causing an acute rise in IOP.6 This event can cause an extremely elevated IOP (possibly up to the 70s), and patients are at risk for vascular occlusions and glaucomatous damage to the optic nerve.

- Optic neuritis

- Etiology: Optic neuritis is an inflammation of the optic nerve that may involve the optic disc (with hyperemia and optic disc swelling). It may alternatively be retrobulbar (with no apparent optic disc changes but more pain on extraocular motions). Demyelinating disease (multiple sclerosis) is the most common etiology in the proper demographic but is often idiopathic.7,8 Atypical optic neuritis should be worked-up in conjunction with an ophthalmologist/neurologist or neuroophthalmologist.

- Symptoms: Sudden vision loss associated with pain with eye movements and significantly reduced acuity.

- Management:

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

- Etiology: Optic neuritis is an inflammation of the optic nerve that may involve the optic disc (with hyperemia and optic disc swelling). It may alternatively be retrobulbar (with no apparent optic disc changes but more pain on extraocular motions). Demyelinating disease (multiple sclerosis) is the most common etiology in the proper demographic but is often idiopathic.7,8 Atypical optic neuritis should be worked-up in conjunction with an ophthalmologist/neurologist or neuroophthalmologist.

Full access? Get Clinical Tree