Open Fundoplication in Children with Gastroesophageal Reflux

Brad W. Warner

The popularity of fundoplication for children with documented gastroesophageal reflux is waxing and waning due to the advent of excellent pharmacologic acid suppression. Further, with the advent of minimally invasive approaches, many pediatric surgeons have adopted laparoscopic fundoplication in their usual armamentarium. However, aside from the obvious cosmetic considerations, the differences between laparoscopic and open fundoplication in the pediatric population are modest with regard to postoperative pain and length of hospitalization. Most studies have compared historical open procedures with more recent laparoscopic approaches; however, the conclusions are less convincing. Despite the advent of laparoscopy and the management of gastroesophageal reflux in children, the open approach is at the very least equivalent in terms of the long-term effects on foregut physiology and durability. Most children requiring antireflux surgery are neurologically impaired and most of the time require more permanent enteral feeding access. The cosmetic benefits of laparoscopy in this patient population are therefore somewhat less of a concern.

The signs and symptoms of significant gastroesophageal reflux may range from being quite obvious to very subtle. One of the more difficult features about reflux is that it is quite common in normal infants and more recent studies have demonstrated that many episodes of what may appear to be significant reflux do subside over time without operative intervention. This, along with some of the preoperative morbidity associated with operative antireflux surgery, has tempered widespread enthusiasm for this intervention in the otherwise normal pediatric population.

In children, several features may place these patients at higher risk for significant perioperative morbidity. These include the premature infant who has abnormal intestinal motility and chronic pulmonary disease related to prematurity. In addition, the presence of spasticity and mental retardation associated with intracranial bleeding poses additional risk. Other adverse comorbidities include neurologic impairment due to metabolic disease, intracranial trauma, or central nervous system (CNS) tumors. Children with severe weight loss secondary to chronic emesis are at increased risk for wound complications and the possibility of postoperative refeeding syndrome must be anticipated. Patients with cystic fibrosis and associated chronic cough and increased intra-abdominal pressure are at greater risk for development of paraesophageal herniation and recurrent reflux symptoms.

One of the most visible signs of reflux is persistent vomiting, which is usually associated with meals and/or tube feeding. Bilious emesis in a pediatric patient is a surgical emergency until proven otherwise and would be inconsistent with simple gastroesophageal reflux. Bilious emesis in a child should mandate an upper gastrointestinal (GI) study to exclude the possibility of rotational abnormality with midgut volvulus.

Exposure of acid to the esophageal mucosa is generally painful. In young infants and children this pain may be associated with meal aversion and failure to thrive. Sandifer syndrome (facial asymmetry and spasmodic torticollis associated with esophageal reflux) occurs when the child twists his or her head in an attempt to straighten the esophagus to promote clearance of the acid. Additional reflux-related symptoms include gagging or retching. Chronic acid injury to the esophagus is not unlike that in adults with esophageal erosion, ulceration, and stricture formation.

In addition to esophageal injury, chronic reflux can affect the respiratory tract from the level of the larynx to the lungs. In acid-induced laryngeal edema, there may be symptoms of hoarseness or chronic cough. Acute acid emersion of the larynx may result in severe laryngospasm and in some cases may be associated with apnea and in more extreme situations sudden infant death syndrome (SIDS). In premature infants, episodes of apnea and bradycardia may be related to reflux and should be considered when all other causes have been excluded. Recurrent pneumonias or episodes of bronchospasm and chronic asthma may also manifest in children with gastroesophageal reflux.

Growth failure with chronic reflux may also be evident as persistent vomiting with inadequate caloric intake being the most common cause. Other mechanisms include food aversion as pain is associated with reflux and gastric distention. More rare causes include protein loss from the denuded esophageal mucosa and chronic illness associated with repeated episodes of aspiration pneumonia.

The minimal preoperative evaluation of children for antireflux surgery should include an upper GI series. This is critical not only for demonstrating obvious reflux, but also for excluding other potential causes of vomiting in the childhood population. These would include anatomic abnormalities such as pyloric stenosis, antral or duodenal webs, annular pancreas, and duodenal stenosis/atresia. Additionally, the esophagus and the angle of His can be evaluated. An obtuse angle of His with a transverse orientation of the stomach is associated with a higher risk of reflux that will be more likely to require operative intervention.

It is important to emphasize that the upper GI contrast study is done not to make the definitive diagnosis of reflux, but to ensure normal gastroesophageal anatomy. The upper GI should not be completely relied upon for making the diagnosis of pathologic reflux since normal episodes of reflux occur frequently in children. In a child with significant frequency of clinical emesis that is uncontrolled with nonoperative measures, an upper GI is probably the only preoperative study needed.

Esophageal Ph Monitoring

Esophageal pH monitoring is perhaps the most sensitive and specific test for the diagnosis of pathologic gastroesophageal reflux. A nasoesophageal catheter is inserted with continuous pH readings recorded during 12- or 24-hour periods from the lower esophagus and midesophagus. The importance of this test is that it can distinguish between pathologic and physiologic reflux. The other value is that the fall in pH associated with reflux can be temporally correlated with clinical features associated with reflux such as signs of discomfort, retching, or cough. Generally, a pH of less than 4 for more than 4% of the measured time is considered abnormal. Limitations of pH monitoring are that bursts of large amounts of gastric contents can result in severe aspiration and can indeed be pathologic; however, the absolute time spent with a low pH measured in the esophagus can be low. A normal result despite pathologic reflux could therefore be evident. The interpretation of this test must therefore be correlated with the clinical presentation.

Radionuclide Gastric Emptying Study

This is a highly sensitive test for gastroesophageal reflux and must therefore be interpreted with caution. This study, due to its extreme sensitivity, cannot distinguish between physiologic and pathologic reflux. The primary value of this test is the detection of reflux in children with very subtle symptoms or in whom all other causes of apnea are excluded. In addition, this test will provide the ability to quantify gastric emptying, which may warrant drainage procedure coupled with antireflux procedure. This latter notion is quite controversial as most gastric emptying will improve with the antireflux procedure alone. Furthermore, the value of a single measurement of delayed gastric measuring is of questionable value since many times on a repeat study the gastric emptying will have normalized.

Esophagoscopy

Endoscopy of the lower esophagus may reveal the presence of Barrett’s esophagitis and long-term endoscopic surveillance is crucial in these patients. Erythema, mucosal friability, and frank ulcer formation are associated with the severity of reflux.

Intraluminal Impedance Esophageal Monitoring

Intraluminal impedance monitoring is an important adjunct in the diagnosis of covert

esophageal reflux in children. The combination of multichannel intraluminal impendence plus pH monitoring allows detection of pH episodes irrespective of changes in pH value. It is therefore important to detect both acid and nonacid reflux. The experience with this diagnostic study in children is growing and certainly may provide additional important information in documenting abnormal gastroesophageal reflux.

esophageal reflux in children. The combination of multichannel intraluminal impendence plus pH monitoring allows detection of pH episodes irrespective of changes in pH value. It is therefore important to detect both acid and nonacid reflux. The experience with this diagnostic study in children is growing and certainly may provide additional important information in documenting abnormal gastroesophageal reflux.

Esophageal Monometry

In children, mean lower esophageal sphincter pressures are lower than in adults and therefore, do not reliably correlate with reflux. Further, since inappropriate relaxation is probably more important than the absolute mean resting lower esophageal sphincter pressure, the use of monometry in making the diagnosis of gastroesophageal reflux has not been valuable.

Medical Management

In the majority of cases, medical management of gastroesophageal reflux in normal children is successful. Several dietary maneuvers may be useful for the control of symptoms and include maintenance of head-elevated position with feeding and during sleep as well as thickened and more frequent and small-volume feedings. Acid-reducing medications serve primarily to reduce the acid injury to the lower esophagus and help with symptoms, but probably do not affect the actual frequency of reflux.

The primary indications for antireflux surgery in the pediatric population include relentless symptoms and/or evidence for persistent endoscopic esophageal acid injury despite a trial of maximal medical management. Generally, several months are permitted for pharmacologic management and observation of the child’s eating patterns, weight gain, and frequency of emesis. Absolute surgical indications for reflux include episodes of near-miss SIDS with significant apnea. It is important that all other causes such as cardiac and neurologic are excluded in these children. Additionally, the presence of an esophageal stricture portends a fairly significant reflux and should warrant operative intervention. Finally, children with severe failure to thrive and stunted growth due to chronic emesis would be an appropriate candidate for antireflux surgery.

In addition to the above absolute indications, general indications would include aspiration pneumonia or severe asthma in situations where pathologic reflux has been identified. Frequently, pediatric surgeons are called to place feeding devices in children who are neurologically impaired. In a comparison of fundoplication plus gastrostomy with a simple transgastric jejunal feeding tube insertion, one study demonstrated increased mechanical complications associated with jejunal feeding tubes and frequent need for repositioning of the tube under radiologic guidance. The benefits of feeding directly into the stomach include the fact that both bolus and continuous feedings may be done whereas in the case of transgastric feeding only continuous feedings are employed. This latter modality may present excessive cost and time burden on family members and/or care providers. Further, since smaller tubes need to be used, the frequency of tube occlusion and dislodgment is greater.

There are multiple procedures designed to address gastroesophageal reflux. In prior years, many different types of operations were employed to address various other factors associated with reflux such as delayed esophageal and/or gastric emptying, stomach size, and surgeons’ personal preference. More recently, the Nissen fundoplication has emerged to be the standard procedure with minor modifications tailored for each patient.

A preoperative first-generation cephalosporin is administered. If it has not been done previously or if a significant period of time has elapsed since a prior study demonstrating significant esophagitis, I perform flexible esophagoscopy just prior to the fundoplication. A significantly inflamed esophagus will provide additional technical challenge during the crural dissection, which is important anticipatory information.

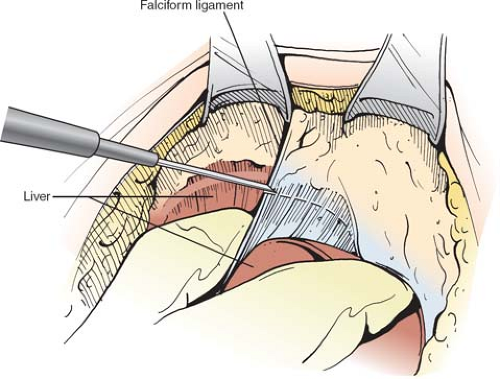

The type of abdominal incision is dictated primarily by the child’s anatomy. In cases where the angle of the lower rib with the sternum is fairly narrow, I prefer an epigastric midline incision. In children with a broad costal margin, a subcostal incision can be employed. Upon entering the peritoneal cavity, the falciform ligament is divided and the membranous component of the ligament that attaches the anterior aspect of the liver to the anterior abdominal wall is taken down with electrocautery to the level of the suprahepatic cava (Fig. 1). This is

done since the liver in neonates and young children is fragile and care must be exercised when it is handled. This also allows for greater mobility of the liver during exposure to the hiatus and helps prevent iatrogenic liver injury during retraction. Next a handheld retractor is held in the left upper quadrant to expose the left triangular ligament. Exposure is facilitated by placing a dry lap pad on the anterior aspect of the left lobe and applying downward and medial traction. A right-angled hemostat is inserted below the ligament and this enables electrocautery dissection of the left lobe away from the diaphragm (Fig. 2). This is done medially to the suprahepatic cava. One landmark to be careful is an inferior phrenic vein. It is often very close to the left hepatic vein and this should be a marker that the dissection has progressed medially as far as needed. The liver is now free from its attachment to the diaphragm and anterior abdominal wall. A self-retaining Thompson retractor is then placed (Fig. 3). I place three Richardson retractors, one in the upper part of the incision just below the sternum and one on either side of the incision. A malleable flat retractor is placed over the liver as the left lateral segment is folded onto itself and retracted to the patient’s right to expose the esophageal hiatus.

done since the liver in neonates and young children is fragile and care must be exercised when it is handled. This also allows for greater mobility of the liver during exposure to the hiatus and helps prevent iatrogenic liver injury during retraction. Next a handheld retractor is held in the left upper quadrant to expose the left triangular ligament. Exposure is facilitated by placing a dry lap pad on the anterior aspect of the left lobe and applying downward and medial traction. A right-angled hemostat is inserted below the ligament and this enables electrocautery dissection of the left lobe away from the diaphragm (Fig. 2). This is done medially to the suprahepatic cava. One landmark to be careful is an inferior phrenic vein. It is often very close to the left hepatic vein and this should be a marker that the dissection has progressed medially as far as needed. The liver is now free from its attachment to the diaphragm and anterior abdominal wall. A self-retaining Thompson retractor is then placed (Fig. 3). I place three Richardson retractors, one in the upper part of the incision just below the sternum and one on either side of the incision. A malleable flat retractor is placed over the liver as the left lateral segment is folded onto itself and retracted to the patient’s right to expose the esophageal hiatus.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree