30 One Health

Interdependence of People, Other Species, and the Planet

I Unprecedented Challenges, Holistic Solutions

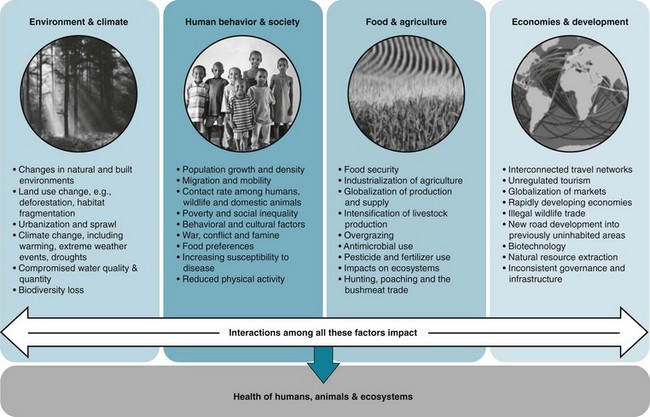

Population growth and the globalization of economic networks have resulted in a rapidly changing, highly interconnected world. The global human population surpassed 7 billion inhabitants in 2011 and is expected to reach 9.3 billion by 2050 and 10 billion by 2100.1 The resulting demands for living space, land, food, water, and energy have become an increasing challenge. Never before have global issues of environmental sustainability and the health of humans and animals been so closely interconnected. To broaden our thinking on the scope and magnitude of these shifting global trends, we introduce a number of anthropological, environmental, and economic issues that ultimately relate to human health (Figure 30-1).

These health and sustainability consequences of global change are economically, socially, medically, and environmentally costly, and as such, their control can be considered a global public good.2 The complexities and breadth of such threats demand interdisciplinary solutions that address the connections between human and animal health,3 as well as the underlying environmental drivers that impact health. Traditionally, however, approaches to health have focused on interventions such as human-based clinical treatment, emergency response, or vaccines. Increasingly, there is a push in the global community to move from reductionist, reactionist approaches to more holistic, preventive approaches that rely on systems thinking.4 One such approach, known as One Health, is a growing global strategy that is being adopted by a diversity of organizations and policy makers in response to the need for integrated approaches. This approach can be relevant to a wide range of global development goals, including the Millennium Development Goals themselves, which we explore in the Chapter 30 supplement on studentconsult.com.

II What is One Health?

One Health can be interpreted differently by various groups and tends to serve as a comprehensive framework that has been employed in different contexts.5 This flexibility can strengthen its applicability rather than narrow its scope. Although different definitions and interpretations exist, a frequently used description follows:

One Health is [characterized by] the collaborative efforts of multiple disciplines working locally, nationally and globally to attain optimal health for people, animals and our environment.6

The One Health approach calls for a paradigm shift in developing, implementing, and sustaining health policies that more proactively engage human medicine, veterinary medicine, public health, environmental sciences, and a number of other disciplines that relate to health, land use, and the sustainability of human interactions with the natural world.6–10 The use of this multifaceted perspective allows practitioners to work toward optimal health for people, domestic animals, wildlife, and the environment concurrently, over multiple spatial and temporal scales. Whereas some may view One Health as having a singular end goal of optimizing human health, we emphasize here that the maintenance and improvement of animal health and ecosystem functioning are also primary goals of One Health, with their own inherent value separate from their impact on human health.

Past global health interventions have generally tackled a single region or a single disease, but One Health offers an integrative, holistic health systems approach that also focuses on “upstream” prevention rather than reactive response. Just as the World Health Organization (WHO) maintains a multifaceted definition of health as “a state of complete physical, mental, and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity,” so too does One Health attempt to address the many different social, environmental, cultural, and physical determinants of human and animal health. Although different interpretations of One Health exist, certain unifying characteristics remain the same across all applications (Box 30-1).

A Relevance to Epidemiology

B Evolution of the Concept

The One Health concept is actually not a new one; its roots date back to ancient times. The Greek physician Hippocrates (ca. 460–370 bce) wrote of the importance of the environment for maintaining health in his text, On Airs, Waters and Places.11 Several centuries later, connections between human and veterinary medicine took shape in the 1800s when Rudolf Virchow (1821–1902), a German physician and pathologist known as the “Father of Comparative Pathology,” laid the foundations for One Health thinking. He defined the term zoonosis (a disease that can be transmitted from animals to people) and stated, “Between animal and human medicine there are no dividing lines—nor should there be.” A student of Virchow’s, the Canadian physician Sir William Osler (1849–1919), once called the “Father of Modern Medicine,” adopted similar ways of thinking about health across both human and veterinary medicine.4 By the 1940s, this type of collaboration took a more distinct form. James Steele, veterinarian and the first U.S. Assistant Surgeon General for Veterinary Affairs, expanded the role of veterinarians by developing the first Veterinary Public Health program within the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and by incorporating veterinarians into the U.S. Public Health Service. Calvin Schwabe (1927–2006), a leading figure in veterinary epidemiology, re-emphasized the importance of veterinary medicine to human health and promoted the term One Medicine in his book, Veterinary Medicine and Human Health.4,12,13

The field of veterinary public health, which holds that the health of wildlife, domesticated animals, and humans is inherently intertwined, solidified as a result of collaborations among major international organizations such as the WHO and the United Nations Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO).12,14 As the concept of sustainable development gained traction in the international arena during the late 1980s, a strengthened recognition of the role of the environment surfaced.4,13 As a result of this trend, some new fields—notably conservation medicine and ecohealth—emerged with a particular emphasis on how the Earth’s changing ecosystems affected the health of both animals and humans.4,14–20 These approaches extended the One Medicine concept to include the whole ecosystem and brought in ideas of sustainable development and socio-ecological influences on health. This represented a move from a more clinical focus to a more holistic view that broadly incorporated the environment and social sciences. This type of perspective contributed greatly to the highly influential and informative Millennium Ecosystem Assessment,21 which further delineated the reliance of human well-being on the environment.

C Manhattan Principles on “One World, One Health”

In 2004 the Wildlife Conservation Society (WCS) brought together an array of partners to develop an unprecedented collaborative One Health framework to launch the One World, One Health initiative.4,5,8 This launch resulted in the development of the Manhattan Principles (Box 30-2), which provide 12 recommendations for “establishing a more holistic approach to preventing epidemic/epizootic disease and for maintaining ecosystem integrity for the benefit of humans, their domesticated animals, and the foundational biodiversity that supports us all.”4,8,22 One World, One Health represented a proactive, collaborative effort among major international agencies and organizations and is seen as an important step in the evolution of One Health.

Box 30-2 Manhattan Principles on “One World, One Health”

1. Recognize the essential link among human, domestic animal, and wildlife health and the threat that disease poses to people, their food supplies, and economies, as well as the biodiversity essential to maintaining the healthy environments and functioning ecosystems we all require.

2. Recognize that decisions regarding land and water use have real implications for health. Alterations in the resilience of ecosystems and shifts in patterns of disease emergence and spread manifest themselves when we fail to recognize this relationship.

3. Include wildlife health science as an essential component of global disease prevention, surveillance, monitoring, control, and mitigation.

4. Recognize that human health programs can greatly contribute to conservation efforts.

5. Devise adaptive, holistic, and forward-looking approaches to the prevention, surveillance, monitoring, control, and mitigation of emerging and resurging diseases that take the complex interconnections among species into full account.

6. Seek opportunities to fully integrate biodiversity conservation perspectives and human needs (including those related to domestic animal health) when developing solutions to infectious disease threats.

7. Reduce the demand for and better regulate the international live-wildlife and bushmeat trade not only to protect wildlife populations but to lessen the risks of disease movement, cross-species transmission, and the development of novel pathogen-host relationships. The costs of this worldwide trade in terms of impacts on public health, agriculture, and conservation are enormous, and the global community must address this trade as the real threat it is to global socioeconomic security.

8. Restrict the mass culling of free-ranging wildlife species for disease control to situations where there is a multidisciplinary, international scientific consensus that a wildlife population poses an urgent, significant threat to human health, food security, or wildlife health more broadly.

9. Increase investment in the global human and animal health infrastructure commensurate with the serious nature of emerging and resurging disease threats to people, domestic animals, and wildlife. Enhanced capacity for global human and animal health surveillance and for clear, timely information-sharing (that takes language barriers into account) can only help improve coordination of responses among governmental and nongovernmental agencies, public and animal health institutions, vaccine/pharmaceutical manufacturers, and other stakeholders.

10. Form collaborative relationships among governments, local people, and the private and public (i.e., nonprofit) sectors to meet the challenges of global health and biodiversity conservation.

11. Provide adequate resources and support for global wildlife health surveillance networks that exchange disease information with the public health and agricultural animal health communities as part of early-warning systems for the emergence and resurgence of disease threats.

12. Invest in educating and raising awareness among the world’s people and in influencing the policy process to increase recognition that we must better understand the relationships between health and ecosystem integrity to succeed in improving prospects for a healthier planet.

From Cook RA, Karesh WB, Osofsky SA: The Manhattan Principles on “One World, One Health”: building interdisciplinary bridges to health in a globalized world, New York, 2004, Wildlife Conservation Society. Available at http://www.oneworldonehealth.org/sept2004/owoh_sept04.html.

This type of interagency collaboration has led to several initiatives, including the subsequent 2006 Beijing Principles.23 Notably, the World Organization for Animal Health (OIE), FAO, and the WHO released a joint strategic concept note to achieve a “world capable of preventing, detecting, containing, eliminating, and responding to animal and public health risks attributable to zoonoses and animal diseases with an impact on food security through multi-sectoral cooperation and strong partnerships.”22,23,24

Other joint partnerships have emerged. In 2007, the American Veterinary Medical Association (AVMA) and the American Medical Association (AMA) both unanimously and explicitly supported One Health.6 The AVMA-AMA collaboration called for the formation of a One Health Commission to work toward the “establishment of closer professional interactions, collaborations, and educational opportunities across the health sciences professions, together with their related disciplines, to improve the health of people, animals, and our environment” (see Websites list at end of chapter). In addition, the One Health Initiative has served as an important global clearinghouse for news and information related to One Health. It collaborates directly with the One Health Newsletter, an online quarterly for One Health articles sponsored by the Florida Department of Health. Through the newsletter and website, communication among One Health professionals all over the world has improved significantly.

Through the evolution of the One Health concept, different—yet complementary and related—approaches have emerged. All these approaches capture dimensions of One Health or have played an important role in the development of One Health. Relevant terms and fields complementary to One Health include One Medicine, comparative medicine, “One World, One Health,” ecohealth, ecosystem approaches to health, veterinary public health, health in socio-ecological systems, conservation medicine, ecological medicine, environmental medicine, medical geology, and environmental health. Similarities also obviously exist between One Health and major fields such as global health, public health, and population health. As it continues to change and evolve, One Health will be strengthened and further defined, extending in scope and in its ability to address complex health and environmental challenges.4

D Disciplines Engaged in One Health

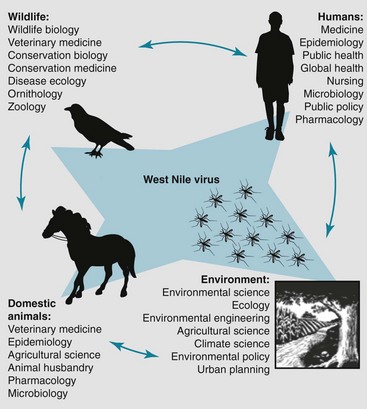

Implementing One Health requires the cooperation of experts from numerous disciplines, including but not limited to the following: human medicine, veterinary medicine, public health, environmental science, ecology, environmental health, conservation biology, dentistry, nursing, social sciences, the humanities, engineering, economics, education, and public policy. Although the foundations of the One Health concept originated within the veterinary and human medical professions, there is a strong push toward representation of a wider array of disciplines. One Health is not to be “owned” by certain disciplines. We illustrate the need for the participation of multiple disciplines when approaching health problems with a particularly relevant case study involving West Nile virus (WNV) (Fig. 30-2). When WNV emerged in New York City in 1999, discovery of the outbreak and development of a control strategy depended upon the involvement of multiple disciplines.25

Figure 30-2 Emergence of West Nile virus (WNV) into the United States.

The collaborative response to WNV in the U.S. provides a perfect case study for the One Health approach. In 1999, physicians noted a strange illness in elderly patients in New York City; simultaneously, veterinary pathologists and epidemiologists were exploring the mysterious deaths of large numbers of crows and exotic birds at the Bronx Zoo. Viral culture and polymerase chain reaction evidence concluded that the infections were related and later confirmed the outbreaks as the first emergence of WNV into the United States via the Culex mosquito vector. WNV can infect several wild bird species and a range of mammals, including: horses, squirrels, dogs, wolves, mountain goats, and humans. Combating WNV requires the collaboration of a multitude of disciplines.

(From Barrett MA, Bouley TA, Stoertz AH, et al: Integrating a One Health approach in education to address global health and sustainability challenges. Frontiers Ecol Environ 9:239–245, 2010. Copyright Ecological Society of America.)

III Breadth of One Health

A Interdependence of Animal, Human, and Ecosystem Health

Fundamentally, the environment affects how organisms live, thrive, and interact and must be considered in order to achieve optimal health for people and animals.21,26–28 By definition, the environment includes “all of the physical, chemical and biological factors and processes that determine the growth and survival of an organism or a community of organisms.”29 This definition encompasses many different contexts and scales, ranging from an individual’s home environment, to social environments, to regional ecosystems, to the air that we breathe and the climate in which we exist. As such, the definition of environment can include both the built environment, such as urban systems, and more unmodified, natural ecosystems.

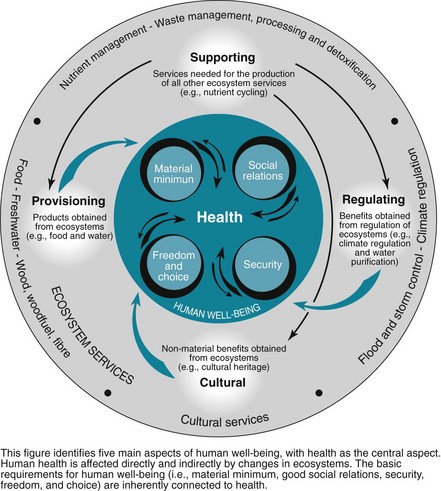

Human and animal well-being relies on the integrity of ecosystems. An ecosystem is “comprised of all of the organisms and their physical and chemical environment within a specific area.”29 Ecosystems underpin processes essential to our survival, known as ecosystem services.21 The United Nations Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, a global and comprehensive global assessment of the world’s ecosystems and what they mean to human well-being, deemed ecosystem services to be the “ultimate foundations of life and health.”21 These services include supporting services (nutrient cycling, soil formation, primary production); regulating services (climate and flood regulation, disease buffering, water purification); provisioning services (food, water, fuel); and cultural services (aesthetic, spiritual, mental health) that make the persistence of human and animal life possible21 (Figure 30-3). Many of these ecosystem services rely on the maintenance of biodiversity (including genes, species, and populations) and complex ecological relationships that make possible the growth of food, healthy diets, the development of new medicines, and the regulation of emerging infectious diseases.

Figure 30-3 Human health relies on essential ecosystem services derived from the environment.

(From Corvalan C, Hales S, McMichael A, et al: Ecosystems and human well-being: health synthesis. Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Geneva, 2005, World Health Organization. Figure from Rekacewicz P, Bournay E, United Nations Environment Programme/Grid-Arendal.)

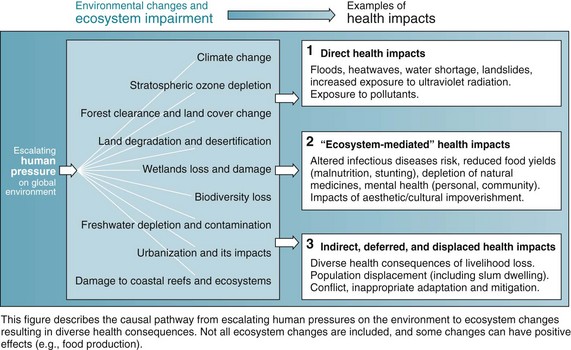

Ecosystems can maintain healthy populations, but when mismanaged or rapidly altered due to human pressure, they can also be associated with disease emergence. Despite the importance of the environment to the preservation of human and animal well-being, we face increasing challenges to the maintenance of healthy ecosystems, including climate change, deforestation, intensification of agricultural systems, freshwater depletion, and resultant biodiversity loss30,31 (Figure 30-4). In fact, human populations have altered ecosystems more rapidly and extensively over the last 60+ years than during any other period in history, causing some scientists to describe our current geologic time period as the Anthropocene (“age of man” or “age of human influence”).21,32 To enable assessment of this change, holistic indicators of ecosystem health (which incorporate environmental, social, and economic aspects of ecosystems) are being developed to assess ecological changes over space and time.33 Ecological indicators can include measures such as water quality, tree canopy cover, soil organic matter, wildlife populations, land-use profiles, and vegetation characteristics.34

Figure 30-4 Environmental change can degrade ecosystems and negatively affect health.

(From Corvalan C, Hales S, McMichael A, et al: Ecosystems and human well-being: health synthesis. Report of the Millennium Ecosystem Assessment, Geneva, 2005, World Health Organization. Figure from Rekacewicz P, Bournay E, United Nations Environment Programme/Grid-Arendal.)

The growing global human population will continue to increase its need for land, food, and energy, yet already 60% of the essential ecosystem services of the planet are degraded or are under increasing threat. Addressing the environmental factors affecting health is essentially a public health–oriented prevention strategy, as it tackles the upstream drivers of disease. For example, an estimated 24% of the global burden of disease, and more than one third of the burden among children, originates from modifiable environmental causes.35,36 Such issues are explored in One Health Case Study 1 on studentconsult.com, which examines a particularly salient case highlighting the emergence of Nipah virus in Malaysia caused by a combination of land-use, agricultural, and environmental factors.

B Climate Change

Climate change is one of the most pressing human-driven environmental changes we face. The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) reported that three main components of climate change will continue to impact ecosystems and health in the future, including warming (1.1°-6.4° C increase in global mean surface temperature by 2100), shifting patterns of precipitation, and increased incidence of extreme climatic events.37 The exact spatial occurrences of these shifts, as well as the resilience and responses of different ecosystems, are difficult to predict.

When examining the impact of climate change on disease, the picture grows more complex. Climate has affected spatial and temporal patterns of disease globally and has been identified as the greatest threat to global health for the 21st century,38–40 yet there is still some debate about exactly how climate change will affect disease burden.41 Changes in temperature, precipitation, and seasonality can influence infectious disease emergence, incidence, and spread (e.g., as seen with dengue, malaria, cholera).42,43 These environmental changes can affect pathogen reproduction, abundance, environmental tolerance, virulence, and distributions.44–47 For example, studies have documented that the chytrid fungus that decimated global amphibian populations partly emerged because of increasing temperatures,48 and that the impacts of malaria, Ross River virus, plague, hantavirus, and cholera have been exacerbated by climate change.39 In addition to disease, the potential health impacts of climate change will be broad and significant in terms of the following: heat and cold effects; wind, storms, and floods; drought, malnutrition, and food security; food safety; water quality; air quality; occupational health; and ultraviolet radiation.37

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree