Obtaining a Patient History

LEARNING OBJECTIVES

• INTRODUCTION

Much of the information needed to accurately assess a patient’s symptom complex is obtained from the patient’s history, acquired by interviewing the patient in a structured method. Because the patient is telling their story, patient histories are referred to as subjective data, whereas laboratory tests, medical imaging test results and the physical examination, are called objective data. The general process to obtain a patient history by the pharmacist starts with broad open-ended questions to begin the interview, followed by more focused open-ended questions to obtain more specific information. Finally, closed-ended questions are used to assess key issues that may be important to the differential diagnosis, but not mentioned earlier in the interview by the patient, or to further clarify information previously obtained. Next, the pharmacist summarizes the information in the history, which allows the patient to verify the accuracy of the pharmacist’s comprehension of the answers they have provided. Closed-ended questions are those that can be answered with a yes or a no and open-ended questions require a more detailed answer in the patient’s own words. Open-ended questions are preferred because their use provides more extensive information than do closed-ended questions. Psychologically, closed-ended questions are generally perceived as a notice that the conversation will be coming to an end soon.

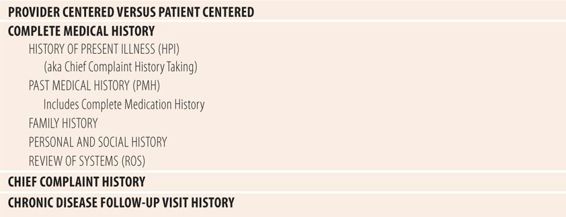

• TYPES OF HISTORIES (Table 2.1)

| TABLE 2.1 | Types of Patient Histories |

Patient histories can be patient-oriented or provider-oriented. Patient-oriented histories explore the patient’s feelings regarding the physical aspects of the symptoms, personal or social components of the symptoms, and the patient’s emotional reactions to the symptoms or disease, with the interviewer liberally using empathy, plus verbal and nonverbal cues such as silence and nodding to get the patient to tell their story. A skilled interviewer using both listening skills and observing nonverbal clues can obtain much of the same information that is obtained using a provider-centered process, plus key elements about other aspects of the illness. However, the interview is controlled mostly by the patient and their agenda and can take more time than other approaches. Provider-centered patient histories are designed to get specific types of information from the patient to use to make a diagnosis, with less attention paid to personal, social, and emotional aspects. Fortunately, the two are not mutually exclusive and elements of both can be easily combined. While this textbook focuses mostly on provider-centered techniques, the reader will recognize the integration of some patient-centered elements.

The complete medical history is used in patients admitted to an inpatient facility, new patients to a provider’s practice, or when the patient’s symptoms do not fit the pattern of a recognizable common disease. Many times, much of this information can be found in the health record especially in an organized health care delivery system (e.g., Group Health, Kaiser, Veterans Administration, Indian Health Service) with integrated inpatient and outpatient health records. Problem lists and one- or two-page health summaries provide much of the information found in a complete medical history. A complete medical history consist of five components: history of present illness (HPI), past medical history, family history, personal/social history, and a review of systems. The HPI, also known as a chief complaint history, focuses on the present symptoms and by itself is the history used in most ambulatory situations, involving acute symptoms. Past medical history includes general health status, infectious diseases and immunizations, adverse reactions to medications, and hospitalizations. It contains both active and inactive problems in a problem list. Personal history includes occupation, marital status, personal habits such as alcohol or smoking, financial status, and current living arrangements. Family history asks about significant health events in the lives of parents, siblings, and offspring, looking for patterns of disease and common causes of death. A review of systems uses open-ended and closed-ended questions to probe for other symptoms or conditions, not found during the HPI; past, family, personal, and social histories; or a review of the health record. It tends to start at the top of the body (head, eyes, ears, nose and throat) and move down, e.g., respiratory, cardiovascular, gastrointestinal, genitourinary tract, etc.

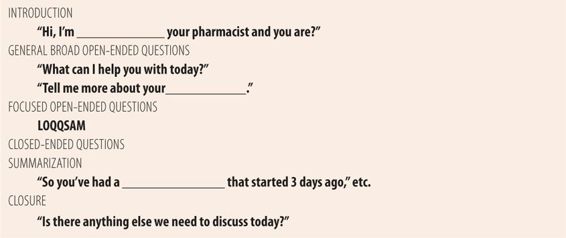

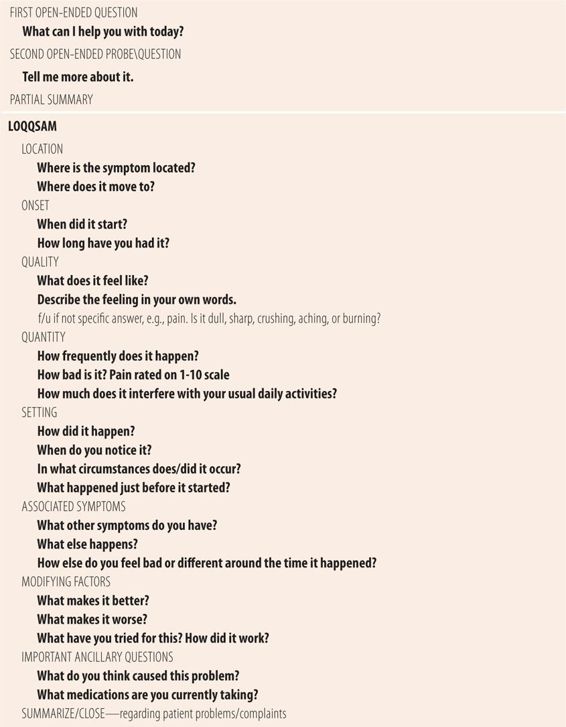

The chief complaint history also known as the HPI is the most commonly used form of medical history. All patient histories begin with this type of history. In the ambulatory setting, many times that is all that is needed to accurately diagnose, with physical examination, laboratory tests, and medical imaging confirming the suspected diagnosis. Table 2.2 outlines the typical step-by-step process of the chief complaint history, and Table 2.3 outlines LOQQSAM, the pneumonic used to remember the structure and content of chief complaint history taking. The focus of the interview should be to characterize the problems as completely as possible, so that when you relate it to another member of the health care team or the patient’s health care provider, they will have all or most of the information they need to assist the patient. That approach prevents the interviewer from jumping to conclusions based on the first few phrases from the patient. Also, it will help obtain enough information to decide whether this patient’s illness can be treated with nonprescription medication or they need to be referred. Normally, the interview starts with introductions including verification of patient identity. “Good morning, I’m Dr. Smith and you are?” After confirming patient identity, address the patient by their name and ascertain the reason for the visit, “Mrs. Jones, what can I help you with today?” If you know the patient, then such formal identification procedures can be dispensed with other than the reason for the visit. A second open-ended statement encourages the patient to begin talking, “Tell me more about your__________.” Patients vary in the amount of information they volunteer from as little as “it’s just a bad cold” to a complete recitation of LOQQSAM. Next, use the appropriate remaining LOQQSAM questions to complete the history. Location questions attempt to find the anatomical location of the symptom and where it may move (radiation). For some symptoms you can omit this question, e.g., a runny nose, cough, sore throat. It is mostly used for pain of any type, or dermatological symptoms. Onset questions are used to assess date/time the symptoms began. Quality questions probe for a detailed description of as many aspects of the symptom as possible. It should be in the patient’s own words if possible. For example, the nature of the patient’s pain can be important to assessing the cause of the pain. If the patient is unable to provide more details, ask, “Exactly how does it feel?” Sometimes, asking “choice” questions will help. “Which of the following would you say best describes your pain: crushing, squeezing, burning, sharp, or cramping?” Quantity questions attempt to measure the severity and/or frequency of the problem. Several approaches can be used, e.g., “How bad is it?” or “How much does this affect your daily routine/work schedule/activities?” For frequency ask, “How often does this happen?” or “How many times a day/hour does it happen?” Setting refers to the circumstances in which the symptom occurs. For example, if the patient complains of crushing, squeezing chest pain, the setting can be very important to determine the next appropriate action step. Consider the difference between the following answers to the question “When does your chest pain occur?” “Oh, only when I’m outside shoveling snow during the winter” would likely indicate chronic stable angina pectoris, while “Well, last night it started while I was just sitting in my recliner watching my favorite TV show” might indicate acute coronary syndrome, which ranges from unstable angina pectoris to the beginning of a myocardial infarction. Associated symptoms looks for other symptoms that may help characterize the symptom pattern to help identify the specific cause. Ask: “What else happens when this occurs?” or “What else do you notice when your symptom starts?” Modifying factors questions are used to find out what makes the symptom better and what makes it worse. Each question should be asked separately. Note that the modifying factors are not always medications. Sometimes certain movements worsen or improve some types of back pain. Avoiding certain foods may improve some gastrointestinal problems. Ask questions such as: “What have you tried to make it better?” or “What seems to make it better?” and “What makes it worse?” Finally, there are two additional questions that can be used to further clarify the situation. The first is to ask the patient what they think caused this problem. “So, what do you think may have caused this?” Sometimes the patient has a good idea of the cause of a given symptom. Sometimes asking a question of this type stimulates the patient to add more information that was not already given. Also, asking the patient their thoughts gives them the idea that their opinion is valued and even implies that they have a role in their own care. The second question is asked whenever you are contemplating recommending a nonprescription product for self-care. “What medications are you currently taking?” This question is intended for patients who are not regular prescription customers. If it is a regular customer you can say, “Let me double-check your medication profile to make sure that what I’m going to suggest won’t cause any problems with your existing therapy.” Finally, you should summarize what the patient has told you. “Just to make sure I got it all, let me summarize what you have told me.” This has several benefits. First, it allows the patient to verify the accuracy and correct any errors. Second, it may prompt the patient to remember something else they forgot to tell you. Finally, it may allow you to detect questions you have not asked or forgot to ask, that may be important in clarifying the diagnosis.

| TABLE 2.2 | Structure of the Chief Complaint History |

| TABLE 2.3 | Chief Complaint History Taking |

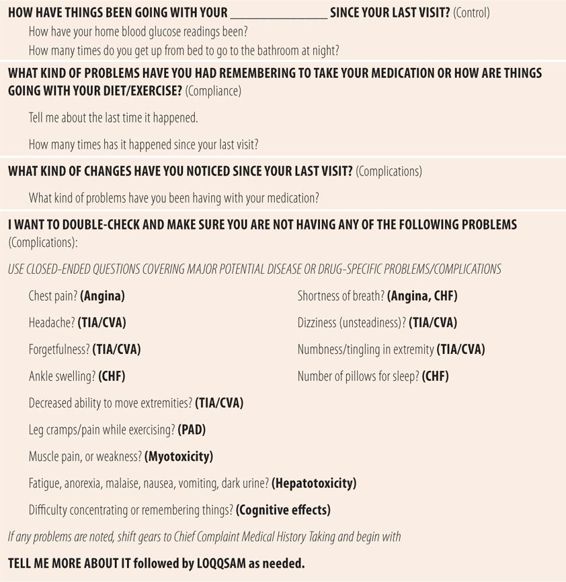

The chronic disease follow-up visit history is the second major type of medical history used by pharmacists to assess patient problems. It is structured around the “3 Cs” schemata of evaluating the quality of care in the patient with chronic diseases. For all chronic diseases, there are three things that need to be evaluated. Control of the disease, compliance with the therapeutic regimen, and complications due to the disease and the drugs used to treat it. In this model, there is a general open-ended question to introduce each of the three areas of interest, plus disease-specific open-ended question for probing more specific issues (Table 2.4). “How have things been going with your diabetes since your last visit?” More specific questions probe other aspects that reflect the nature of control of the disease. “How have your home blood glucose readings been going?” “How many times do you get up to go to the bathroom after you go to bed at night?” Compliance questions such as “What kind of problems have you had remembering to take your medication?” “When was the last time it happened?” and “What do you think caused it to happen?” are questions used to probe for details of missed doses. “How have things been going with your exercise (or diet)?” probes for adherence to other therapeutic modalities. Objective data from the patient’s pharmacy profile, weight, and resting pulse are objective indicators of diet and exercise. Discrepancies between objective and subject parameters require further probing. “What kind of problems or changes have you noticed since your last visit?” opens the discussion regarding complications from the disease and adverse effects from the medication regimen. Any positive response requires further probing most likely using LOQQSAM. If the patient does not volunteer any problems or changes, then a series of disease and drug-specific, closed-ended questions can be used to double-check for the presence of symptoms that might represent the presence of any complications due to the disease or medication used to treat it. Begin with “I just want to make sure you are not having any of the following: chest pain, breathing problems, etc.” Any yes answers will require probing with LOQQSAM beginning with “Tell me more about your chest pain.” Using multiple closed-ended questions also signals to the patients that the visit is nearing its end. Going over these lists of complications also educates the patient what to look for. When you routinely ask the open-ended question about problems or changes, you may get a rewarding answer, e.g., “Well you always ask about chest pain and I have had several episodes since I saw you last” or they may call you the first time it happens and ask what to do. Finally, the pharmacist can periodically ask about a fourth C, concern. “What kind of concerns do you have about your diabetes or its treatment?” This is a patient-centered question that can be used frequently at the beginning of their treatment and anytime the conversation or nonverbal clues potentially hint at some issue. This reminds them that the pharmacist wants to know about their concerns and it encourages them to ask even though it is not asked about at every visit.

| TABLE 2.4 | General Approach to Interviewing Patients Returning for Chronic Disease Follow-Up |

• OTHER SKILLS USED IN HISTORY TAKING

As discussed previously, verification of patient identity and the introduction are important to beginning the history. Also important to a successful history is a private environment. Patients will be more open and forthcoming in a private environment. A private room, like an exam room, office, or counseling room would be best. Semiprivate consultation booths or areas can be used effectively. However, many times the design of the community pharmacy precludes optimal privacy. If the patient is the only one in the pharmacy or near the pharmacy, then conducting the history anywhere would be private. If a private or semiprivate area in or immediately around the pharmacy is unavailable, take the patient to a quiet aisle containing nonprescription medications. Patient comfort is also important. In a private room the patient should be seated in a backed, comfortable chair. In many situations, especially follow-up visits for chronic diseases have the patient remain dressed while you take the history. Sitting in a cold room, in a thin paper gown is not very conducive to accurate and complete patient responses. Even if you are sure that some disrobing will be required, take the history first, while the patient is dressed. Then step outside and begin documentation of the history in the patient’s record, while the patient disrobes in preparation for the physical examination. The use of verbal and nonverbal encouragement helps the patient provide more complete information, plus they demonstrate that the provider/pharmacist is very interested in what the patient is saying. Examples of verbal encouragement include: “Mm-hmmm, I see, Tell me more, Go on, Oh?, And?, What else?” Clarification of a patient’s statement and further discussion can be done with more directed verbal encouragers such as “For instance?” or “Give me an example.” Silence is a powerful nonverbal encouragement technique because in many cultures silence during a conversation causes psychological discomfort, encouraging one party to end the discomfort by speaking. Nodding, a surprised facial expression, direct eye contact (when appropriate), and interested facial expressions are all effective nonverbal ways to encourage further discussion by the patient. Patients may express emotion during the history. In these instances, reflecting or empathetic responses are used to explore and acknowledge those feelings, help them calm down and demonstrate a caring attitude by the interviewer. Summarization has also been discussed previously in this chapter. It usually occurs at the end of the history, but is also appropriate at other parts of the interview, especially if the interview is lengthy or the patient’s response is complex or confusing. Finally, the visit should be ended with a closure statement in the form of a closed-ended question such as “Is there anything else we need to discuss today?”

There are patient scripts at the end of this chapter so students can practice both types of patient histories that are frequently used by pharmacists. Chief complaint history taking cases can be used concurrently with the symptom-specific diagnostic schemata tables to also practice differential diagnosis. Similarly, chronic disease follow-up visits require concurrent use of the disease-specific tables, which contain subjective parameters used to evaluate disease control, adherence (compliance) to the therapeutic regimen, and complications due to the disease and drug therapy.

• KEY REFERENCES

1. Henderson MC, Tierney LM, Smetana GW. The Patient History: Evidence-Based Approach to Differential Diagnosis. New York: McGraw-Hill; 2012.

2. Boyce RW, Herrier RN. Obtaining and using patient data. Am Pharm. 1991;NS31:65-70.

3. Haidet P, Paterniti DA. Building a patient history rather than taking one. Arch Intern Med. 2003;163:1134-1140.

4. Platt FW, Gaspar DL, Coulehan JL, et al. Tell me about yourself: the patient-centered interview. Ann Intern Med. 2001;134:1079-1085.

PATIENT SCRIPT TO PRACTICE CHIEF COMPLAINT HISTORY-TAKING

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree

CASE 2.1

CASE 2.1