EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient displays ocular deviation, take his vital signs immediately and assess him for an altered level of consciousness (LOC), pupil changes, motor or sensory dysfunction, and a severe headache. If possible, ask the patient’s family about behavioral changes. Is there a history of recent head trauma? Respiratory support may be necessary. Also, prepare the patient for emergency neurologic tests such as a computed tomography (CT) scan.

History and Physical Examination

If the patient isn’t in distress, find out how long he has had the ocular deviation. Is it accompanied by double vision, eye pain, or a headache? Also, ask if he’s noticed associated motor or sensory changes or a fever.

Check for a history of hypertension, diabetes, allergies, and thyroid, neurologic, or muscular disorders. Then obtain a thorough ocular history. Has the patient ever had extraocular muscle imbalance, eye or head trauma, or eye surgery?

During the physical examination, observe the patient for partial or complete ptosis. Does he spontaneously tilt his head or turn his face to compensate for ocular deviation? Check for eye redness or periorbital edema. Assess the patient’s visual acuity, and then evaluate extraocular muscle function by testing the six cardinal fields of gaze.

Medical Causes

- Brain tumor. The nature of ocular deviation depends on the site and extent of the tumor. Associated signs and symptoms include headaches that are most severe in the morning, behavioral changes, memory loss, dizziness, confusion, vision loss, motor and sensory dysfunction, aphasia and, possibly, signs of hormonal imbalance. The patient’s LOC may slowly deteriorate from lethargy to coma. Late signs include papilledema, vomiting, increased systolic blood pressure, widening pulse pressure, and decorticate posture.

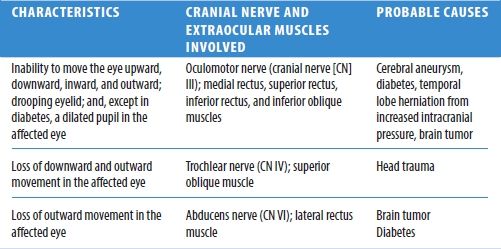

Ocular Deviation: Its Characteristics and Causes in Cranial Nerve Damage

- Cavernous sinus thrombosis. With cavernous sinus thrombosis, ocular deviation may be accompanied by diplopia, photophobia, exophthalmos, orbital and eyelid edema, corneal haziness, diminished or absent pupillary reflexes, and impaired visual acuity. Other features include a high fever, a headache, malaise, nausea and vomiting, seizures, and tachycardia. Retinal hemorrhage and papilledema are late signs.

- Diabetes mellitus. A leading cause of isolated third cranial nerve palsy, especially in the middle-aged patient with long-standing mild diabetes, diabetes mellitus may cause ocular deviation and ptosis. Typically, the patient also complains of the sudden onset of diplopia and pain.

- Encephalitis. Encephalitis causes ocular deviation and diplopia in some cases. Typically, it begins abruptly with a fever, a headache, and vomiting, followed by signs of meningeal irritation (for example, nuchal rigidity) and neuronal damage (for example, seizures, aphasia, ataxia, hemiparesis, cranial nerve palsies, and photophobia). The patient’s LOC may rapidly deteriorate from lethargy to coma within 24 to 48 hours after onset.

- Head trauma. The nature of ocular deviation depends on the site and extent of head trauma. The patient may have visible soft tissue injury, bony deformity, facial edema, and clear or bloody otorrhea or rhinorrhea. Besides these obvious signs of trauma, he may also develop blurred vision, diplopia, nystagmus, behavioral changes, a headache, motor and sensory dysfunction, and a decreased LOC that may progress to coma. Signs of increased intracranial pressure — such as bradycardia, increased systolic pressure, and widening pulse pressure — may also occur.

- Orbital blowout fracture. In orbital blowout fracture, the inferior rectus muscle may become entrapped, resulting in limited extraocular movement and ocular deviation. Typically, the patient’s upward gaze is absent; other directions of gaze may be affected if edema is dramatic. The globe may also be displaced downward and inward. Associated signs and symptoms include pain, diplopia, nausea, periorbital edema, and ecchymosis.

- Orbital tumor. Ocular deviation occurs as the tumor gradually enlarges. Associated findings include proptosis, diplopia and, possibly, blurred vision.

- Stroke. Stroke, a life-threatening disorder, may cause ocular deviation, depending on the site and extent of the stroke. Accompanying features are also variable and include an altered LOC, contralateral hemiplegia and sensory loss, dysarthria, dysphagia, homonymous hemianopsia, blurred vision, and diplopia. In addition, the patient may develop urine retention or incontinence or both, constipation, behavioral changes, a headache, vomiting, and seizures.

- Thyrotoxicosis. Thyrotoxicosis may produce exophthalmos — proptotic or protruding eyes — which, in turn, causes limited extraocular movement and ocular deviation. Usually, the patient’s upward gaze weakens first, followed by diplopia. Other features are lid retraction, a wide-eyed staring gaze, excessive tearing, edematous eyelids and, sometimes, an inability to close the eyes completely. Cardinal features of thyrotoxicosis include tachycardia, palpitations, weight loss despite increased appetite, diarrhea, tremors, an enlarged thyroid, dyspnea, nervousness, diaphoresis, heat intolerance, and an atrial or a ventricular gallop.

Special Considerations

Continue to monitor the patient’s vital signs and neurologic status if you suspect an acute neurologic disorder. Take seizure precautions, if necessary. Also, prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as blood studies, orbital and skull X-rays, and a CT scan.

Patient Counseling

Explain the disorder, its treatment, and changes in LOC that need to be reported. Provide information about maintaining a safe environment and teach ways to avoid environmental stress.

Pediatric Pointers

In children, the most common cause of ocular deviation is nonparalytic strabismus. Normally, children achieve binocular vision by age 4 months. Although severe strabismus is readily apparent, mild strabismus must be confirmed by tests for misalignment, such as the corneal light reflex test and the cover test. Testing is crucial — early corrective measures help preserve binocular vision and cosmetic appearance. Also, mild strabismus may indicate retinoblastoma, a tumor that may be asymptomatic before age 2 except for a characteristic whitish reflex in the pupil.

REFERENCES

Ansons, A. M., & Davis, H. (2014). Diagnosis and management of ocular motility disorders. West Sussex, UK: Wiley Blackwell.

Gerstenblith, A. T., & Rabinowitz, M. P. (2012). The wills eye manual. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Roy, F. H. (2012). Ocular differential diagnosis. Clayton, Panama: Jaypee–Highlights Medical Publishers, Inc.

Oligomenorrhea

In most women, menstrual bleeding occurs every 28 days, plus or minus 4 days. Although some variation is normal, menstrual bleeding at intervals of greater than 36 days may indicate oligomenorrhea — abnormally infrequent menstrual bleeding characterized by three to six menstrual cycles per year. When menstrual bleeding does occur, it’s usually profuse, prolonged (up to 10 days), and laden with clots and tissue. Occasionally, scant bleeding or spotting occurs between these heavy menses.

Oligomenorrhea may develop suddenly, or it may follow a period of gradually lengthening cycles. Although oligomenorrhea may alternate with normal menstrual bleeding, it can progress to secondary amenorrhea.

Because oligomenorrhea is commonly associated with anovulation, it’s common in infertile, early postmenarchal, and perimenopausal women. This sign usually reflects abnormalities of the hormones that govern normal endometrial function. It may result from ovarian, hypothalamic, pituitary, thyroid, and other metabolic disorders and from the effects of certain drugs. It may also result from emotional or physical stress, such as sudden weight change, a debilitating illness, or rigorous physical training.

History and Physical Examination

After asking the patient’s age, find out when menarche occurred. Has the patient ever experienced normal menstrual cycles? When did she begin having abnormal cycles? Ask her to describe the pattern of bleeding. How many days does the bleeding last, how frequently does it occur, and how many pads or tampons does she use? Are there clots and tissue fragments in her menstrual flow? Note when she last had menstrual bleeding.

Next, determine if she’s having symptoms of ovulatory bleeding. Does she experience mild, cramping abdominal pain 14 days before she bleeds? Is the bleeding accompanied by premenstrual symptoms, such as breast tenderness, irritability, bloating, weight gain, nausea, and diarrhea? Does she have cramping or pain with bleeding? Also, check for a history of infertility. Does the patient have children? Is she trying to conceive? Ask if she’s currently using hormonal contraceptives or if she has ever used them in the past. If she has, find out when she stopped taking them.

Then ask about previous gynecologic disorders such as ovarian cysts. If the patient is breast-feeding, has she experienced problems with milk production? If she hasn’t been breast-feeding recently, has she noticed milk leaking from her breasts? Ask about recent weight gain or loss. Is the patient less than 80% of her ideal weight? If so, does she claim that she’s overweight? Ask if she’s exercising more vigorously than usual.

Screen for metabolic disorders by asking about excessive thirst, frequent urination, or fatigue. Has the patient been jittery or had palpitations? Ask about headaches, dizziness, and impaired peripheral vision. Complete the history by finding out what drugs the patient is taking.

Begin the physical examination by taking the patient’s vital signs and weighing her. Inspect for increased facial hair growth, sparse body hair, male distribution of fat and muscle, acne, and clitoral enlargement. Note if the skin is abnormally dry or moist, and check hair texture. Also, be alert for signs of psychological or physical stress. Rule out pregnancy by a blood or urine pregnancy test.

Medical Causes

- Adrenal hyperplasia. In adrenal hyperplasia, oligomenorrhea may occur with signs of androgen excess, such as clitoral enlargement and male distribution of hair, fat, and muscle mass.

- Anorexia nervosa. Anorexia nervosa may cause sporadic oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea. Its cardinal symptom, however, is a morbid fear of being fat associated with weight loss of more than 20% of ideal body weight. Typically, the patient displays dramatic skeletal muscle atrophy and loss of fatty tissue; dry or sparse scalp hair; lanugo on the face and body; and blotchy or sallow, dry skin. Other symptoms include constipation, a decreased libido, and sleep disturbances.

- Diabetes mellitus. Oligomenorrhea may be an early sign in diabetes mellitus. In insulin-dependent diabetes, the patient may have never had normal menses. Associated findings include excessive hunger, polydipsia, polyuria, weakness, fatigue, dry mucous membranes, poor skin turgor, irritability and emotional lability, and weight loss.

- Hypothyroidism. Besides oligomenorrhea, hypothyroidism may result in fatigue; forgetfulness; cold intolerance; unexplained weight gain; constipation; bradycardia; decreased mental acuity; dry, flaky, inelastic skin; puffy face, hands, and feet; hoarseness; periorbital edema; ptosis; dry, sparse hair; and thick, brittle nails.

- Prolactin-secreting pituitary tumor. Oligomenorrhea or amenorrhea may be the first sign of a prolactin-secreting pituitary tumor. Accompanying findings include unilateral or bilateral galactorrhea, infertility, loss of libido, and sparse pubic hair. A headache and visual field disturbances — such as diminished peripheral vision, blurred vision, diplopia, and hemianopia — signal tumor expansion.

- Thyrotoxicosis. Thyrotoxicosis may produce oligomenorrhea along with reduced fertility. Cardinal findings include irritability, weight loss despite increased appetite, dyspnea, tachycardia, palpitations, diarrhea, tremors, diaphoresis, heat intolerance, an enlarged thyroid and, possibly, exophthalmos.

Other Causes

- Drugs. Drugs that increase androgen levels — such as corticosteroids, corticotropin, anabolic steroids, danocrine, and injectable and implanted hormonal contraceptives — may cause oligomenorrhea. Hormonal contraceptives may be associated with delayed resumption of normal menses when their use is discontinued; however, 95% of women resume normal menses within 3 months. Other drugs that may cause oligomenorrhea include phenothiazine derivatives and amphetamines and antihypertensive drugs, which increase prolactin levels.

Special Considerations

Prepare the patient for diagnostic tests, such as blood hormone levels, thyroid studies, or pelvic imaging studies.

Patient Counseling

Teach the patient techniques of recording basal body temperature and explain the use of a home ovulation test, if appropriate. Provide information about the use of contraceptives, if prescribed.

Pediatric Pointers

Teenage girls may experience oligomenorrhea associated with immature hormonal function. However, prolonged oligomenorrhea or the development of amenorrhea may signal congenital adrenal hyperplasia or Turner’s syndrome.

Geriatric Pointers

Oligomenorrhea in the perimenopausal woman usually indicates the impending onset of menopause.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012). Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

Schuiling, K. D. (2013). Women’s gynecologic health. Burlington, MA: Jones & Bartlett Learning.

Sommers, M. S., & Brunner, L. S. (2012) Pocket diseases. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Oliguria

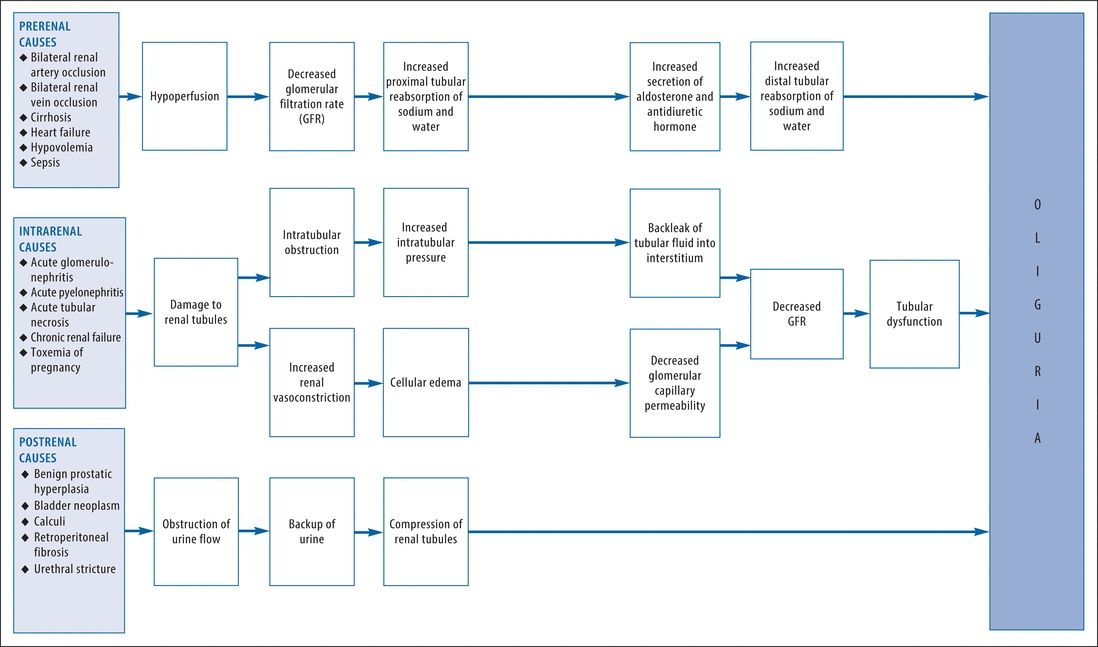

A cardinal sign of renal and urinary tract disorders, oliguria is clinically defined as urine output of less than 400 mL/24 hours. Typically, this sign occurs abruptly and may herald serious — possibly life-threatening — hemodynamic instability. Its causes can be classified as prerenal (decreased renal blood flow), intrarenal (intrinsic renal damage), or postrenal (urinary tract obstruction); the pathophysiology differs for each classification. (See How Oliguria Develops, pages 528 and 529.) Oliguria associated with a prerenal or postrenal cause is usually promptly reversible with treatment, although it may lead to intrarenal damage if untreated. However, oliguria associated with an intrarenal cause is usually more persistent and may be irreversible.

History and Physical Examination

Begin by asking the patient about his usual daily voiding pattern, including frequency and amount. When did he first notice changes in this pattern and in the color, odor, or consistency of his urine? Ask about pain or burning on urination. Has the patient had a fever? Note his normal daily fluid intake. Has he recently been drinking more or less than usual? Has his intake of caffeine or alcohol changed drastically? Has he had recent episodes of diarrhea or vomiting that might cause fluid loss? Next, explore associated complaints, especially fatigue, loss of appetite, thirst, dyspnea, chest pain, or recent weight gain or loss (in dehydration).

How Oliguria Develops

Check for a history of renal, urinary tract, or cardiovascular disorders. Note recent traumatic injury or surgery associated with significant blood loss as well as recent blood transfusions. Was the patient exposed to nephrotoxic agents, such as heavy metals, organic solvents, anesthetics, or radiographic contrast media? Next, obtain a history of any prescribed or over-the-counter drugs the patient takes.

Begin the physical examination by taking the patient’s vital signs and weighing him. Assess his overall appearance for edema. Palpate both kidneys for tenderness and enlargement and percuss for costovertebral angle (CVA) tenderness. Also, inspect the flank area for edema or erythema. Auscultate the heart and lungs for abnormal sounds and the flank area for renal artery bruits. Assess the patient for edema or signs of dehydration such as dry mucous membranes.

Obtain a urine sample and inspect it for abnormal color, odor, or sediment. Use reagent strips to test for glucose, protein, and blood. Also, use a urinometer to measure specific gravity.

Medical Causes

- Acute tubular necrosis (ATN). An early sign of ATN, oliguria may occur abruptly (in shock) or gradually (in nephrotoxicity). Usually, it persists for about 2 weeks, followed by polyuria. Related features include signs of hyperkalemia (muscle weakness and cardiac arrhythmias), uremia (anorexia, confusion, lethargy, twitching, seizures, pruritus, and Kussmaul’s respirations), and heart failure (edema, jugular vein distention, crackles, and dyspnea).

- Calculi. Oliguria or anuria may result from calculi lodging in the kidneys, ureters, bladder outlet, or urethra. Associated signs and symptoms include urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, and hematuria or pyuria. Usually, the patient experiences renal colic — excruciating pain that radiates from the CVA to the flank, the suprapubic region, and the external genitalia. This pain may be accompanied by nausea, vomiting, hypoactive bowel sounds, abdominal distention and, occasionally, a fever and chills.

- Cholera. In cholera, which is a bacterial infection, severe water and electrolyte loss lead to oliguria, thirst, weakness, muscle cramps, decreased skin turgor, tachycardia, hypotension, and abrupt watery diarrhea and vomiting. Death may occur in hours without treatment.

- Glomerulonephritis (acute). Acute glomerulonephritis produces oliguria or anuria. Other features are a mild fever, fatigue, gross hematuria, proteinuria, generalized edema, elevated blood pressure, a headache, nausea and vomiting, flank and abdominal pain, and signs of pulmonary congestion (dyspnea and a productive cough).

- Heart failure. Oliguria may occur in left-sided heart failure as a result of low cardiac output and decreased renal perfusion. Accompanying signs and symptoms include dyspnea, fatigue, weakness, peripheral edema, jugular vein distention, tachycardia, tachypnea, crackles, and a dry or productive cough. In advanced or chronic heart failure, the patient may also develop orthopnea, cyanosis, clubbing, a ventricular gallop, diastolic hypertension, cardiomegaly, and hemoptysis.

- Hypovolemia. Any disorder that decreases circulating fluid volume can produce oliguria. Associated findings include orthostatic hypotension, apathy, lethargy, fatigue, gross muscle weakness, anorexia, nausea, profound thirst, dizziness, sunken eyeballs, poor skin turgor, and dry mucous membranes.

- Pyelonephritis (acute). Accompanying the sudden onset of oliguria in acute pyelonephritis are a high fever with chills, fatigue, flank pain, CVA tenderness, weakness, nocturia, dysuria, hematuria, urinary frequency and urgency, and tenesmus. The urine may appear cloudy. Occasionally, the patient also experiences anorexia, diarrhea, and nausea and vomiting.

- Renal failure (chronic). Oliguria is a major sign of end-stage chronic renal failure. Associated findings reflect progressive uremia and include fatigue, weakness, irritability, uremic fetor, ecchymoses and petechiae, peripheral edema, elevated blood pressure, confusion, emotional lability, drowsiness, coarse muscle twitching, muscle cramps, peripheral neuropathies, anorexia, a metallic taste in the mouth, nausea and vomiting, constipation or diarrhea, stomatitis, pruritus, pallor, and yellow- or bronze-tinged skin. Eventually, seizures, coma, and uremic frost may develop.

- Renal vein occlusion (bilateral). Bilateral renal vein occlusion occasionally causes oliguria accompanied by acute low back and flank pain, CVA tenderness, a fever, pallor, hematuria, enlarged and palpable kidneys, edema and, possibly, signs of uremia.

- Toxemia of pregnancy. In severe preeclampsia, oliguria may be accompanied by elevated blood pressure, dizziness, diplopia, blurred vision, epigastric pain, nausea and vomiting, irritability, and a severe frontal headache. Typically, oliguria is preceded by generalized edema and sudden weight gain of more than 3 lb (1.4 kg) per week during the second trimester, or more than 1 lb (0.45 kg) per week during the third trimester. If preeclampsia progresses to eclampsia, the patient develops seizures and may slip into coma.

- Urethral stricture. Urethral stricture produces oliguria accompanied by chronic urethral discharge, urinary frequency and urgency, dysuria, pyuria, and a diminished urine stream. As the obstruction worsens, urine extravasation may lead to formation of urinomas and urosepsis.

Other Causes

- Diagnostic studies. Radiographic studies that use contrast media may cause nephrotoxicity and oliguria.

- Drugs. Oliguria may result from drugs that cause decreased renal perfusion (diuretics), nephrotoxicity (most notably, aminoglycosides and chemotherapeutic drugs), urine retention (adrenergics and anticholinergics), or urinary obstruction associated with precipitation of urinary crystals (sulfonamides and acyclovir).

Special Considerations

Monitor the patient’s vital signs, intake and output, and daily weight. Depending on the cause of oliguria, fluids are normally restricted to between 0.6 and 1 L more than the patient’s urine output for the previous day. Provide a diet low in sodium, potassium, and protein.

Laboratory tests may be necessary to determine if oliguria is reversible. Such tests include serum blood urea nitrogen and creatinine levels, urea and creatinine clearance, urine sodium levels, and urine osmolality. Abdominal X-rays, ultrasonography, a computed tomography scan, cystography, and a renal scan may be required.

Patient Counseling

Explain fluid and dietary restrictions the patient needs.

Pediatric Pointers

In neonates, oliguria may result from edema or dehydration. Major causes include congenital heart disease, respiratory distress syndrome, sepsis, congenital hydronephrosis, acute tubular necrosis, and renal vein thrombosis. Common causes of oliguria in children ages 1 to 5 are acute poststreptococcal glomerulonephritis and hemolytic-uremic syndrome. After age 5, causes of oliguria are similar to those in adults.

Geriatric Pointers

In elderly patients, oliguria may result from the gradual progression of an underlying disorder. It may also result from overall poor muscle tone secondary to inactivity, poor fluid intake, and infrequent voiding attempts.

REFERENCES

Berkowitz, C. D. (2012) Berkowitz’s pediatrics: A primary care approach (4th ed.). USA: American Academy of Pediatrics.

Buttaro, T. M., Tybulski, J., Bailey, P. P., & Sandberg-Cook, J. (2008). Primary care: A collaborative practice (pp. 444–447). St. Louis, MO: Mosby Elsevier.

Colyar, M. R. (2003). Well-child assessment for primary care providers. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. Davis.

Lehne, R. A. (2010). Pharmacology for nursing care (7th ed.). St. Louis, MO: Saunders Elsevier.

Opisthotonos

A sign of severe meningeal irritation, opisthotonos is a severe, prolonged spasm characterized by a strongly arched, rigid back; a hyperextended neck; the heels bent back; and the arms and hands flexed at the joints. Usually, this posture occurs spontaneously and continuously; however, it may be aggravated by movement. Presumably, opisthotonos represents a protective reflex because it immobilizes the spine, alleviating the pain associated with meningeal irritation.

Usually caused by meningitis, opisthotonos may also result from subarachnoid hemorrhage, Arnold-Chiari syndrome, and tetanus. Occasionally, it occurs in achondroplastic dwarfism, although not necessarily as an indicator of meningeal irritation.

Opisthotonos is far more common in children — especially infants — than in adults. It’s also more exaggerated in children because of nervous system immaturity. (See Opisthotonos: Sign of Meningeal Irritation, page 532.)

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

EMERGENCY INTERVENTIONS

If the patient is stuporous or comatose, immediately evaluate his vital signs. Employ resuscitative measures, as appropriate. Place the patient in bed, with side rails raised and padded, or in a crib.

Stay updated, free articles. Join our Telegram channel

Full access? Get Clinical Tree