Identifying the at-risk patient is limited by the tools available. Several scoring systems can quantify the risk of complications—particularly septic complications— following blunt or penetrating trauma. In multiple trials, enteral nutrition improves outcome by reducing sepsis compared with starvation or parenteral feeding (

7,

8,

9,

10,

11,

12). Trauma patients are not traditionally considered nutritionally at risk because most are young and well nourished, although alcohol and drug abuse are common. General surgical patients with preexisting nutritional deficits have been harder to stratify because specialized scoring systems do not exist, although several principles apply. Preoperative albumin (ALB) is the single best indicator of postoperative complications and mortality following major surgery (

13), but low ALB may reflect liver disease, fluid resuscitation, or inflammation, rather than nutritional status.

The Trauma Patient

In most studies, the Injury Severity Score (ISS) (

14), Abdominal Trauma Index (ATI) (

15), or both have stratified patients to complication risk. The ISS scores the three most severely injured body regions of the six, which include head and neck, musculoskeletal, soft tissue, abdominal, thoracic, or head. The ISS correlates with mortality and morbidity. In randomized prospective studies, early enteral feeding improves the outcome of patients with an ISS greater than 18 to 20 compared with intravenous (IV) feeding or fasting (

15).

The ISS underestimates risk when severe injuries are isolated to a single body area. The ATI identifies risk for infection in patients with intra-abdominal injuries (

Table 93.1) (

15). Each intra-abdominal organ has a risk factor that when multiplied by the magnitude of that organ’s injury, correlates with risk of sepsis from that injury. Injuries to the pancreas, colon, major vascular structures, duodenum, and liver pose the highest risk. The ATI can be calculated during surgery by summing the scores of each injured organ. An ATI greater than or equal to 20 to 25 poses the greatest risk for sepsis. Sepsis rates are also high with ATI values less than 20 if injuries such as severe pulmonary and chest wall injury, severe closed head injury, spinal cord injury, major soft tissue injuries, or multiple lower extremity fractures exist. These patients have an ISS greater than 20. With ATI greater than 20 to 25 or ISS greater than or equal to 18 to 20, enteral nutrition is usually tolerated and reduces septic complications (

9,

12).

General Surgical Patients

Severely malnourished patients are susceptible to wound dehiscence, infections, anastomotic leaks, and so on. With no gold standard to determine nutritional status, a complete history and physical examination, determination of body weight changes, and the use of select serum tests help identify risk for nutrition-related complications.

The simplest screen is a history and physical with identification of unintentional weight loss because a strong correlation exists between impaired protein status and postoperative complications (

16). Unintentional weight loss greater than 10% occurring over 6 months with increased metabolic requirements indicates nutritional risk. Two calculations are commonly used (

17):

or

Symptoms of abdominal pain, chronic diarrhea, anorexia, or lethargy often accompany weight change. Anthropometric measurements, creatinine-height index, and delayed cutaneous hypersensitivity to a battery of antigens are rarely used in practice currently (

18,

19,

20). Assessment of lymphocyte count or lymphocyte transformation also is not specific. Protein-calorie malnutrition decreases ALB synthesis, but a decrease in protein degradation can maintain serum levels. This occurs with marasmus when protein and calorie intake are severely restricted. Lower levels of constitutive transport proteins such as ALB (

t½ = 21 days), transferrin (TFN;

t½ = 8 days), or thyroxin-binding prealbumin (

t½ = 2-3 days) may reflect the degree of malnutrition (

21). However, inflammatory conditions (e.g., trauma, sepsis, peritonitis) increase serum interleukin-6 (IL-6), which stimulates the acute phase protein response (

22) to increase C-reactive protein (CRP) and α-1-acid glycoprotein (AAG) and reduce constitutive protein production. Therefore, initial protein assessment should include CRP with ALB or prealbumin. Low constitutive proteins with a low CRP more likely indicate preexisting malnutrition. Elevated CRP with depressed constitutive proteins may reflect inflammation, protein-calorie malnutrition, or both.

Combinations of these parameters have been used in predictive models to quantify risk. The Prognostic Nutritional Index (PNI) (

23) is calculated as follows:

PNI (%) = 158 − 16.6 (ALB) − 0.78 (TSF) − 0.20 (TFN) − 5.8 (DH) where PNI is the percentage of risk of complication, ALB is serum ALB in g/dL, TSF is the triceps skinfold thickness in millimeters, TFN is the serum TFN in mg/dL, and DH is delayed hypersensitivity reactive to one of three recall antigens. With DH, 0 = nonreactive; 1 = less than 5 mm induration; and 2 = greater than 5 mm induration. Because DH is rarely used, an alternative applies a lymphocyte score of 0 to 2, where

0 = less than 1000 total lymphocytes/mm

3; 1 = 1000 to 2000/mm

3 and 2 = greater than 2000/mm

3. ALB drives the results, rendering it susceptible to nonnutritional factors such as inflammation, preexisting liver disease, and edema. The PNI predicts complications better than ALB alone (

24).

The Prognostic Inflammatory and Nutrition Index (PINI) (

23,

24,

25) correlates recovery with acute phase and constitutive proteins as follows:

CRP, AAG, and prealbumin are measured in mg/dL, whereas ALB is measured in g/dL. Because the AAG elevation and ALB depression are prolonged and slow to recover, CRP and PA drive the equation, although sensitivity and specificity are lost when AAG and ALB are not included.

The Subjective Global Assessment (SGA) (

26,

27) examines changes in organ function and body composition, the disease process, and the restriction of nutrient intake to predict nutrition status. The SGA is more valuable than anthropometry, which suffers from interob-server variability, hydration state, and age.

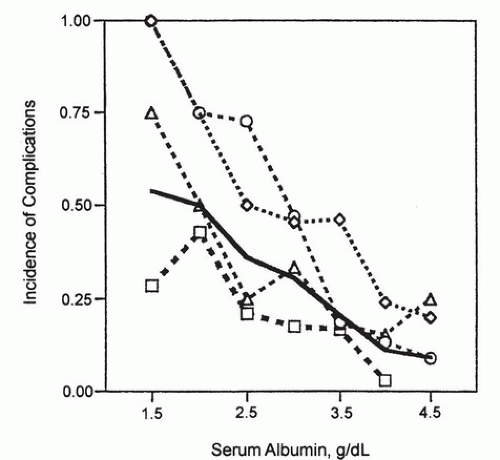

The most stressful gastrointestinal (GI) operations are esophagectomy and pancreatic surgery. Complications increase as preoperative ALB levels drop in elective surgery on these organs (

Fig. 93.1) (

28). Patients undergoing esophagectomy with ALB less than 3.5 g/dL or pancreatic or gastric operations with ALB less than 3.25 g/dL have increased risk for major postoperative complications; risk increases as ALB drops.